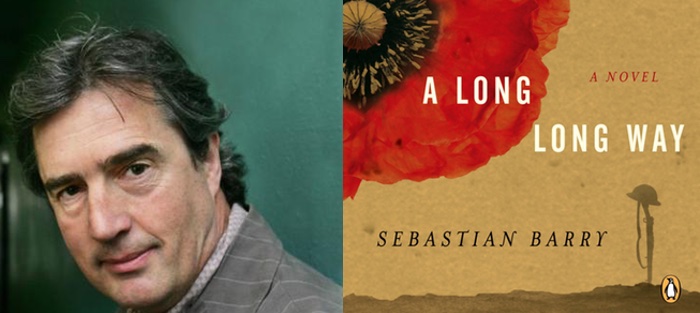

I dreamed of Willie Dunne. A fictional character has never appeared in my dreams before, so how did Sebastian Barry’s Willie Dunne, from A Long Long Way (Faber & Faber, 2005), come out of the streets of Dublin, out of the fields of Flanders, and out of the brutal trenches of World War I to find his way into my dreams? In my dream, Willie was a shadow, a shade, a figure with no distinct face, and it was that—that lack of clear physical features—that led me to the realization that Willie slid into my dreams on the backs of metaphors and similes, on figurative language that seeps into the subconscious.

Willie—like all of the characters in A Long Long Way, in fact—is a character constructed primarily through simile. Willie is the main character in the novel, and while we hear him sing “like an angel” and watch him move through streets and battles, it is difficult to summon a physical image, to picture him (or, indeed, any character in the novel). The only specific physical description we are given is Willie’s height, a feature that is significantly connected to his fate through a simile: as Willie was growing up, his father marked his height “religiously” by putting him “up against the wall like a fella to be shot at dawn.” Because Willie only grows to be “five foot six,” he cannot become a Dublin policeman like his father, so decides to go to war instead, ultimately sacrificing his life. We are not told the color of Willie’s eyes or hair; we are not told the shape of his face or the slant of his nose. We are told that he was “like a scrap” when he was born, “like a featherless pigeon,” and that as he grew, “[h]is muscles were like wraps of prime meat to make a butcher happy.” These similes, as well as the one that put Willie against the wall “like a fella to be shot,” invoke characteristics such as vulnerability, insignificance, and fragility; issues such as religion and politics; and acts such as slaughter and execution, setting the tone for the similes that mark almost every page of the novel. The overall effect of these similes is to emphasize the fragility of life and the inhumanity of war.

Willie—like all of the characters in A Long Long Way, in fact—is a character constructed primarily through simile. Willie is the main character in the novel, and while we hear him sing “like an angel” and watch him move through streets and battles, it is difficult to summon a physical image, to picture him (or, indeed, any character in the novel). The only specific physical description we are given is Willie’s height, a feature that is significantly connected to his fate through a simile: as Willie was growing up, his father marked his height “religiously” by putting him “up against the wall like a fella to be shot at dawn.” Because Willie only grows to be “five foot six,” he cannot become a Dublin policeman like his father, so decides to go to war instead, ultimately sacrificing his life. We are not told the color of Willie’s eyes or hair; we are not told the shape of his face or the slant of his nose. We are told that he was “like a scrap” when he was born, “like a featherless pigeon,” and that as he grew, “[h]is muscles were like wraps of prime meat to make a butcher happy.” These similes, as well as the one that put Willie against the wall “like a fella to be shot,” invoke characteristics such as vulnerability, insignificance, and fragility; issues such as religion and politics; and acts such as slaughter and execution, setting the tone for the similes that mark almost every page of the novel. The overall effect of these similes is to emphasize the fragility of life and the inhumanity of war.

Just as Willie is “like a scrap” at birth—small, minute, meager, insubstantial—the soldiers, throughout the novel, are thrown into the trenches like scraps, inconsequential, disposable; as quickly as the men die they are replaced, “changing all the time, like a tube emptying at the top and filling at the bottom.” And those men who do live through the book’s bloody battles become like scraps of their former selves, compared repeatedly to ghosts: Willie is “like the ghost of the war” when he returns on furlough; Willie and Gretta (the girl he is in love with) “lay down […] like ghosts, floating souls”; Willie and his battalion approach Dublin “like very ghosts”; Willie and his mates are hailed as heroes after a battle in Guinchy, but “they were ghosts in their hearts”; Willie visiting his dead Captain’s parents is “like a grey ghost”; and at the end, on his last furlough home before he is killed, the similes return Willie back to a “scrap”: “He felt like a ghost […]. He felt like just wisps and scraps of a person.” These similes that compare Willie and his fellow soldiers to scraps and ghosts imbue the novel (and the war it describes) with a sense of futility; Willie is born a “scrap” and dies a “scrap,” and in between walks through life like a ghost. These similes also call attention to the absence of fully-fleshed out physical descriptions of Willie and the other characters, an absence which in turn reinforces the weakness of the human body but the relative strength of the soul. This sense of fragility of the human form and continuation of the soul is beautifully illustrated through a metaphor invoked in the aftermath of a particularly brutal battle: “The breeze rustled through the small woodlands, and in the trees hung the paper bodies of lost men, the patterns of their expended souls.” This metaphor presents bodies as paper, the patterns from which souls are sewn, scraps and all.

While many of the comparisons emphasize those “paper bodies” of the characters—their immaterial, ghostly, floating selves—other similes and metaphors running through the novel emphasize the physical bodies of the characters—their corporeal, sinewed, solid selves. While Willie’s muscles are like “wraps of prime meat,” for example, a dead German is “like a whippet [….] all bone and sinew.” The “first-aid post” is “a sort of pigsty of blood and entrails,” and when soldiers die, “warm ballooning armfuls of entrails spill” out. Willie feels “like there were lice in his blood,” and war turns the hearts of many soldiers black, “like the hearts of slaughtered cows.” Similes and metaphors such as these—emphasizing the physical, corporeal nature of the characters—may initially seem at odds with the emphasis on the characters as ghosts, “lost men” with “paper bodies.” But what similes such as these do is position the men as animals to be used, trained, ridden, slaughtered, and the ultimate effect of this—in addition to emphasizing the inhumanity of war—is to separate the characters even further from their physical selves. By comparing the soldiers to animals—emphasizing their meat, bones, sinew, blood, entrails—the similes position their bodies as “other”; this in turn reinforces the idea of the characters as shadows, souls with temporary bodies, with skin that could fall “off like a dress.” At the same time, the comparison of muscles to “wraps of prime meat,” arms to “bone[s] and sinew[s],” and insides to “armfuls of entrails,” figuratively dismembers the characters, pulls them apart to be wrapped, sold, and eaten (like a bull Willie later sees slaughtered to feed the men). The dismemberment suggested by the figurative language also clearly echoes the literal dismemberment of men in battle, “[m]en with half their faces gone and limbs lost,” and, more broadly, it reflects the fragmentation of nations, countries, families, “the world […] distressed into a thousand pieces.”

Similes that directly compare Willie and the soldiers to animals further fragment and separate the characters’ bodies and souls and, at the same time, use the image of slaughter to make a political statement about Ireland’s fight for independence. Throughout the novel, similes and metaphors compare the soldiers to a variety of creatures, including sheepdogs, cattle, dogs, rats, horses, snakes, pigs, and mice. While similes that compare the men to these and other animals reinforce the submissive, inferior, expendable position of the soldiers at war, similes that compare the men to fish and lamb call attention both to the fraught relationship between Great Britain and Ireland and to the divided opinions in Ireland about independence. When Willie finds his battalion inexplicably ordered back into Dublin to fight an “enemy” that turns out to be his own countrymen, for example, the blood of a dying young man (fighting for Home Rule) is “thrown over Willie again and again like a fisherman’s net.” Caught in that figurative, inescapable, and bloody net of national conflict, Willie later imagines himself as a fish in the “underworld” caught and eaten by the “great Lord of everything.” And by the end of the novel, Willie imagines that his “soul [has been] filleted out of him”—the figurative language sharply and clearly separates his body and soul, and attributes this separation, through the strands of the bloody fishing net, to the fighting at home in Ireland.

The comparisons of Willie and the other soldiers to lambs likewise focus the reader’s attention on the fight for Irish independence, a fight that runs beneath the surface of the main narrative, but that rises to the top through the figurative language. As Willie watches new soldiers arrive to replace those who have died, for example, he sees “[f]locks and flocks and flocks of them,” like “King George’s lambs.” This comparison of the soldiers to lambs prepares the reader for another, more pointed comparison, later in the novel. As Willie is leaving Dublin after a furlough, he remembers being at the docks with his father when he was young, “watch[ing] the Irish lambs being loaded on, for the English trade, his father checking the manifests so that the numbers tallied.” Taking the two comparisons together, we can easily see that the “lambs being loaded on” here, as Willie prepares to go back to war, are the Irish soldiers, being sent for the English war, with Willie’s own father, a Loyalist, unwittingly complicit in sending his son to slaughter. The similes and metaphors in these instances work to bring a more subversive narrative to the surface of the novel.

It’s no wonder that Willie Dunne walked into my dreams from the pages of A Long Long Way. His story is an incredibly haunting one, and the contours of his “five foot six” self—as well as (I’m sure) his much taller soul—are shaded and shaped by similes that wrap around you and wind their way into your subconscious. In addition to shaping and filling in characters, these similes act like beacons in the novel, pointing the way (through some very dark and horrific scenes) to key ideas and themes, such as the inhumanity of war, the fragility of life, and the persistence of the soul. I still can’t see Willie Dunne’s face, but thanks to the similes in A Long Long Way, I think I can see his soul.