“V.S. Naipaul wouldn’t survive in today’s market,” said my opponent in the debate.

We stood on the barn porch at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, enjoying what had until then been a spirited but non-adversarial conversation about the state of contemporary literature. He was a fellow early-career fiction writer, somewhat younger than I but more established, who of course shall not be named.

“But it’s not about today’s market,” I countered.

“Yes it is,” he insisted. “It’s all about today’s market.”

“We agree to disagree,” I told him, reaching my plastic cup out to his in an attempt at

a truce-bringing toast.

To my surprise, he pulled his cup away. I finished my beverage in a swig and headed back to my dorm room, amazed at how passionately my opponent held his belief in the power of the market. I was also amazed at how clearly, and perhaps unwittingly, he and I had drawn a line in the sand. If push comes to shove, we will all have to fall on one side of this line or the other: we either write to participate in the marketplace or write to participate in the tradition of literature. Though the two intertwine—sometimes brilliantly and fruitfully—they are ultimately separate streams, and we must remain practiced in the art of discerning them.

When I got back to my room I thought how odd this conversation felt at Bread Loaf, the 82-year-old brainchild of Robert Frost which predated and served as a blueprint for many of America’s creative writing workshops and MFA programs. I thought, too, about my opponent’s assessment of V.S. Naipaul. It’s quite possibly true that, his 2001 Nobel Prize notwithstanding, Naipaul might not make the kind of impact as an emerging writer today as he did at the start of his career. His prose is too turgid, some would say, or his material too dark. But great books tend to find their way into readers’ hands despite the changing moods of the marketplace. A House for Mr. Biswas and A Bend in the River would certainly interest publishers even today, when the market trends toward a less studied prose than those books offer. Some publisher—perhaps a mom-and-pop operation that will grow into the next Grove/Atlantic Press or New Directions—would note the integrity of the work and bring it into the world.

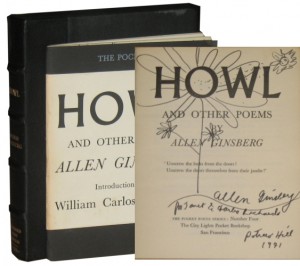

This is true for one simple reason: literature does not depend on the market for validation. A look at any “great books” list will reveal many titles and authors first published by then-tiny presses: City Lights, which gave us Ginsberg’s Howl, or Contact Publishing in Paris, which gave us Hemingway’s debut volume Three Stories and Ten Poems.

So the assertion that V.S. Naipaul “wouldn’t survive in today’s market” is neither

right nor wrong—it’s simply beside the point. We might just as productively say the same of Jane Austen, Geoffrey Chaucer, or Homer. The market has it own life that is determined by readers’ tastes, changing distribution channels, corporate risk tolerance, and industry-wide competition. Readers and publishers alike are happy in the fortuitous moments when the market and literature intersect, and when a great book appears on shelves all over the world. But we must remember that such events represent a convergence of two streams; both of them need to exist in order for books to reach a wide range of readers, but neither one is dependent on the other. We cannot allow the stream of the market to stand in for the stream of literature any more than we can do the reverse.

Yet this is precisely what my opponent in the aforementioned argument did. Those who place the market first risk falling into a trap described well in a dictum attributed to the 20th century German poet Gottfried Benn: “He who writes for the market will always be a slave to the market.” But that decision is entirely personal, and need not have any impact on the writing of those who make other choices. Authors whose primary allegiance is to the marketplace have existed since the birth of movable type, but they have not destroyed literature. Doomsayers and glass-half-empty types—those who proclaim the death of the novel and the irrelevance of poetry—are quick to blame today’s marketplace for “ruining” serious writing, as if wishing for the return of an imaginary time when readers devoured only the classics and turned up their noses at popular work.

At its root, however, this argument is just as specious as that made by my opponent at Bread Loaf. We cannot forget that the marketplace is its own entity, shaped by its own forces, that does not have an explicit impact on literature; nor is it necessarily affected by literature. What the mega-conglomerates publish has no intrinsic bearing on what you create at your desk while under the spell of your personal Muse; the sale of a publishing house to a multinational corporation does not inherently alter the course of your novel or poem. The market will certainly affect your career and your ability to make a living as a writer; but it only affects your art to the extent that you allow it.

Literary work has no obligation to accommodate the vicissitudes of the market. And the market, likewise, has no obligation to publish your literary work unless it sees a payoff. There are more than enough books written with the market in mind, rather than literature in mind, for the market to function entirely without literature if it so chooses. Somehow the two have managed to coexist, with varying degrees of chumminess and acrimony, for centuries. But they are separate entities, and it does no one any good to conflate them. The stream of literature—determined by the bravest work of its most talented and inspired writers—has long continued its meandering course regardless of how violently today’s marketplace may differ from yesterday’s or tomorrow’s. It survives regardless of how the market staggers (as it does today) through rampant mergers and acquisitions, through disruptions in distribution and delivery channels, through uncertainties about the electronic future, and through the quick-changing interests of the reading public. And the marketplace survives regardless of literature, too.

In the end, the choice is always personal. Every writer must decide, with every individual project, what role the market will take in its shaping. But we owe the market nothing, and the market owes us nothing in return. Only those who decide to write for it need follow its strictures. So while it’s fine to say “it’s all about today’s market” in regard to one’s own work, making that claim about the endeavor of writing in toto is a grave mistake.

I do not fear for literature, which has endured purges of all kinds, the death of the novel, the irrelevance of poetry, centuries without general literacy, and every other threat that has been hurled its way. Enough people hold it dear, and it is intrinsic enough to the human identity, for it to survive whatever problems plague it now. But I do fear for those young writers whose primary teaching in their craft is market-centered rather than literature-centered. I fear that they will go through the nascent phases of their careers—those crucial years in which they wrestle with their craft, with their masters living and dead, with their evolving place in the writing world—while guided by a temporary, temperamental star called “today’s market” that constantly, almost whimsically, changes position. It is crucial for young writers to understand the marketplace, if for no other reason than to learn the challenges inherent in building a career out of doing what they love. But trusting the market’s guidance, rather than the tangible models of literature itself, may leave them with much to un-learn.

About the Author

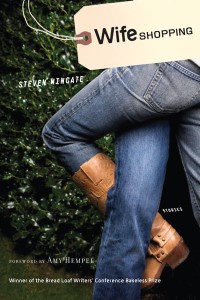

Steven Wingate’s short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. His stories, reviews, and hybrid-genre work have appeared in such venues as Gulf Coast, The Pinch, the Mississippi Review, the Colorado Review, and Brand (UK). He spends his analog time in Colorado, where he teaches at the University of Colorado, and his digital time at www.stevenwingate.com.

Steven Wingate’s short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. His stories, reviews, and hybrid-genre work have appeared in such venues as Gulf Coast, The Pinch, the Mississippi Review, the Colorado Review, and Brand (UK). He spends his analog time in Colorado, where he teaches at the University of Colorado, and his digital time at www.stevenwingate.com.