You know how this ends. Because you’ve been here before—maybe not this particular table or this bar, but one just like it. You glance at the glowing blue clock on the wall and think, Time to go, and when another song follows seamlessly the one before, think again: Yes, definitely time. But when the crucial moment arrives you order another whiskey-soda and settle in as the big fellow with the scarred forehead sitting across from you, who is definitely much drunker than you are, who could drink you under this table with both arms tied behind his back (he tells you) and still manage to stagger to his writing desk tomorrow morning at 5 a.m., rheumy eyes ablaze with genius, yes! genius!—as this fellow goes on talking at you, telling you the score: on women, on writing and writers (Faulkner: hysterical drunk; Tolstoy: goddamn great but wrecked himself in the end with all that God nonsense), on war, and above all and always—always—death.

You smile, you nod.

You’ve been smiling and nodding all night, it seems, and every time you do, another quarter drops silently into the slot: it’s all encouragement for the fellow sitting across from you. You know this, and yet you can’t help yourself. It’s not just the whiskey or your tendency toward politeness, it’s not just this habit you have of allowing strangers to tell you their crazy, often baroquely complicated stories, a habit you’ve long cultivated (and was that such a good idea? you’re asking yourself now: was it, really?). No, mostly it’s because this fellow with the scar on his forehead (2 a.m. accident with a skylight, Paris: you’ve seen the picture taken afterward with Sylvia Beach outside Shakespeare and Company, the thick white bandage, the sheepish, aw hell grin) is—or was, once—something of an idol to you. He was the writer whose short stories opened to you an entirely new world, even as they cast a shadow across that world. “A Soldier’s Home,” “Hills Like White Elephants,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”—stories which, when you first read them, struck the thick brass rim of whatever soul you have inside you with such a clean clear beautiful sound, such resonance, that for years afterward whenever you sat down and wrote you had that same sound—those stories with their clipped, lovely, lugubrious cadences—ringing through you, for better or worse. You’ve ordered another drink when really you should have called it a night and headed home (because you, too, have to get up tomorrow morning and write, you too have work to do), and with that drink now sitting on the bar in front of you, weeping its little shining ring of water onto the wood, you’ve no choice but to sit here and listen to this endless disquisition on love and war and death, even if it kills you.

You’ve been smiling and nodding all night, it seems, and every time you do, another quarter drops silently into the slot: it’s all encouragement for the fellow sitting across from you. You know this, and yet you can’t help yourself. It’s not just the whiskey or your tendency toward politeness, it’s not just this habit you have of allowing strangers to tell you their crazy, often baroquely complicated stories, a habit you’ve long cultivated (and was that such a good idea? you’re asking yourself now: was it, really?). No, mostly it’s because this fellow with the scar on his forehead (2 a.m. accident with a skylight, Paris: you’ve seen the picture taken afterward with Sylvia Beach outside Shakespeare and Company, the thick white bandage, the sheepish, aw hell grin) is—or was, once—something of an idol to you. He was the writer whose short stories opened to you an entirely new world, even as they cast a shadow across that world. “A Soldier’s Home,” “Hills Like White Elephants,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”—stories which, when you first read them, struck the thick brass rim of whatever soul you have inside you with such a clean clear beautiful sound, such resonance, that for years afterward whenever you sat down and wrote you had that same sound—those stories with their clipped, lovely, lugubrious cadences—ringing through you, for better or worse. You’ve ordered another drink when really you should have called it a night and headed home (because you, too, have to get up tomorrow morning and write, you too have work to do), and with that drink now sitting on the bar in front of you, weeping its little shining ring of water onto the wood, you’ve no choice but to sit here and listen to this endless disquisition on love and war and death, even if it kills you.

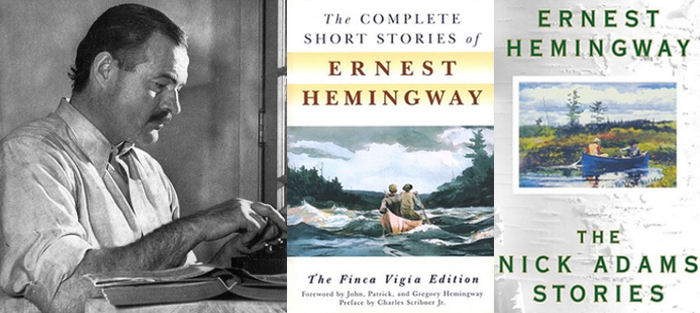

Recently I watched and for a few hours fell under the spell of Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen’s loving but slyly wary reminder of the allure and danger of nostalgia, particularly when that nostalgia is for an era you’ve never yourself actually experienced—in this case, Paris in the 1920s with its dazzling, dizzying cast of modernist giants: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Salvador Dali, Cole Porter, and of course the irreplaceable, all-too-imitable Ernest Hemingway (in this case, Corey Stoll’s hilariously pugnacious, self-parodying Hemingway). It’s a funny, very sweet film, in my opinion one of Allen’s better films lately, and I certainly enjoyed the ride, so much so that in its warm afterglow I plucked from my library my well-thumbed edition of The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway (the Finca Vigía edition named for Hemingway’s “Lookout Farm” home in Cuba), a book that collects not only those stories for which Hemingway is still deservedly anthologized (I first encountered “Soldier’s Home” in an introductory literature course as a freshman in college), but the stories Hemingway wrote in what well should have been his artistic prime—that is, in his forties and fifties—with all that rich experience, all those bullfights and big fish, not to mention several wars, behind him.

And yes, there they were, my old friends: “In Another Country,” “The Killers,” “Now I Lay Me,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” and of course the technically masterful “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” and perhaps my favorite of all Hemingway’s stories, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” a story which for years seemed to me to perfectly sum up the plight of every writer: too many stories to tell, too little time. But amply scattered among these gems were a good many—a great many, I realized sadly—real stinkers. By this I don’t mean Hemingway’s early work; after all, a writer has to build from something, and even in his earliest published fiction (“Up In Michigan,” for example) you could see Hemingway finding his way, becoming, in no small sense, temperamentally, stylistically, the Hemingway he would become. With these stories he was learning how to write, how he wanted to write, and even if I now found much of the writing itself rather labored and dull (when did that happen?), I wasn’t particularly troubled. No, what bothered (or perhaps perplexed me; that’s the better word: perplexed) me were the stories (and I’m quoting the book itself here) “Published in Books or Magazines Subsequent to ‘The First Forty-Nine.’” That is, the stories few of us rarely if ever read today, unless you are, or were, like me, rather wide-eyed in your admiration. “The Butterfly and the Tank,” “Night Before Battle,” “Get a Seeing-Eye Dog,” to name just a few.

John Updike once famously warned of celebrity being the mask that eventually eats into your face, and here, in these stories, I saw that warning come to its awful fruition: every second story seems to be told by a famous writer of a certain age wearily dragging himself from battlefield to bar, dispensing as he does his wide-ranging opinions on violence, death, sex, wine, and the utter futility of it all. The flowering one might have reasonably hoped for, reading “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (written when Hemingway was only in his mid-thirties), has within a decade withered away. What the hell happened? I found myself wondering, when I damn well knew, I suppose. (After all, I’d read the biographies, all of them, years ago.) It’s very much as if the self-quoting Hemingway Corey Stoll created in Midnight in Paris has, with the appropriate middle-age padding added and considerably less hair, stepped back in front of the camera and continued to hold forth, glass in one hand, pen in the other.

John Updike once famously warned of celebrity being the mask that eventually eats into your face, and here, in these stories, I saw that warning come to its awful fruition: every second story seems to be told by a famous writer of a certain age wearily dragging himself from battlefield to bar, dispensing as he does his wide-ranging opinions on violence, death, sex, wine, and the utter futility of it all. The flowering one might have reasonably hoped for, reading “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (written when Hemingway was only in his mid-thirties), has within a decade withered away. What the hell happened? I found myself wondering, when I damn well knew, I suppose. (After all, I’d read the biographies, all of them, years ago.) It’s very much as if the self-quoting Hemingway Corey Stoll created in Midnight in Paris has, with the appropriate middle-age padding added and considerably less hair, stepped back in front of the camera and continued to hold forth, glass in one hand, pen in the other.

And of course it’s not as if Hemingway hadn’t show signs in his early work (and even in his best work, to be honest) of certain tics that would, in time, wreck his writing. Glimmers here and there: a certain woodenly over-masculine, clumsily maudlin tendency which, were it to appear in a character in a short story by, say, Chekhov or Mavis Gallant or Saul Bellow, would almost certainly be punctured by the time the curtain fell. But no, Hemingway meant this. This isn’t parody, this is the real thing, folks. Life is terrifying and ultimately tragic, death lurks around every corner, ready to clobber you over the head at any second, just as you’re skipping happily along, and there isn’t a goddamn thing you can do about it except sip your brandy and wait, and watch the shadows the streetlamp makes through the leaves.

Well, I thought.

Which isn’t to say Hemingway—and I mean the Ernest Hemingway who actually wrote those marvelous but ultimately not always so blindingly marvelous stories—wasn’t a wonderful writer. He was. I can still read that exquisite opening of “In Another Country” and feel that ineffable lift, that clear, almost musical ringing, just as I can reread A Farewell to Arms—in my opinion Hemingway’s best novel, his only truly “great” novel, whatever that means—without ever wondering what all the fuss was about. But he is, one inevitably discovers, largely a young writer’s writer, and you’ve been sitting here too long to pretend that the big fellow with the scarred forehead is even listening to himself anymore.

So. Time to go.