Let a butterfly land on your hand. You know that it started out life as a caterpillar, something humbler that could only crawl, and yet now it has wings. You take hold of the wings and tear them off. Look, you say, it was only an insect after all.

Years ago, when I was an MFA student, a classmate looked down the table at the man who had written the short story we were discussing that day. “Did this really happen?” she asked. I looked away because I knew what was about to happen. “That’s immaterial,” he said, and refused to engage. The writer in question was older than the rest of the students in the room. He was a Vietnam vet—he’d made no secret of that—and the story we were workshopping was set during the Vietnam War and narrated by a young American soldier. Asking him whether it was true was, perhaps, tempting, but it was also intrusive and unnecessary. He slapped her down, and rightly so.

Alternatively, he might have responded, “No,” “Yes,” “None of your damn business,” “I’m not telling,” or even, “Is that a real question?” The immediate effect of his answer was two-fold: on the one hand, it killed any discussion of autofiction we might otherwise have had that day, but it also backfired oddly in that it was a warning—his pointing out the “No Trespassing” sign we hadn’t noticed before—that reinforced the idea that there was something there to be warned away from.

We accepted his veteran’s authority in writing the story in the first place, so why wasn’t that enough? Why pry? If he’d simply answered “No,” some people in the room might have accepted that the story had been built from his experiences as a soldier, without documenting any particular event. More of us, I suspect, would have thought that he was lying, obfuscating in order to avoid more painful revelations. Ironically, if he had answered, “Yes,” everyone in that classroom would have dropped his metaphorical dirty linen back in the hamper and left him alone, but he would then also have been diminished as a writer of fiction.

We accepted his veteran’s authority in writing the story in the first place, so why wasn’t that enough? Why pry? If he’d simply answered “No,” some people in the room might have accepted that the story had been built from his experiences as a soldier, without documenting any particular event. More of us, I suspect, would have thought that he was lying, obfuscating in order to avoid more painful revelations. Ironically, if he had answered, “Yes,” everyone in that classroom would have dropped his metaphorical dirty linen back in the hamper and left him alone, but he would then also have been diminished as a writer of fiction.

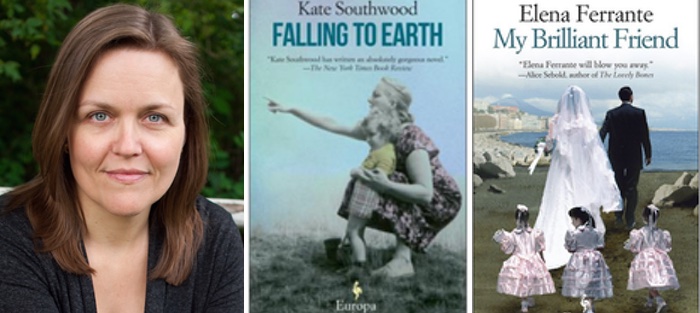

The Italian writer Elena Ferrante has famously taken the “No Trespassing” sign to new heights by writing pseudonymously and refusing to promote her own work. Ferrante and I share a publisher, Europa Editions, who publish Ferrante in English translation and who published my first novel, Falling to Earth (Europa Editions). I’m typically late to catch on to literary trends, but when my editor sent me a copy of My Brilliant Friend, “Ferrante Fever” had not yet struck and so I had the curious experience of watching the phenomenon unfold in real time. When I first read about Ferrante’s insistence that her work end with each book’s completion, it struck me as reckless and starry-eyed, even as I admired her resolve. This was uncharted territory: I felt as if I had discovered a rare breed of cat with a set of traits I recognized, but which were configured in ways I had never considered or imagined possible before.

I was in Florence last October visiting friends when the news broke that a journalist had unmasked Ferrante’s legal identity. It was odd to be in Italy that day, when my host greeted me not with “Good Morning,” but with “Did you see the news?” The unmasking was condemned in the press, but the credibility of the deduction went unchallenged. Then, with the anguished outcry from Ferrante’s fans and fellow writers still hanging in the air, everyone held their collective breath. Would she stop publishing, as she had promised to do if her identity were ever revealed?

In the event, Ferrante ignored it. She seems not to have responded at all to the scrutiny of the biographical facts of her actual life, not even to the ensuing indignation that arose when those facts did not correspond with the lives of her fictional characters. The ungovernable desire to dissect and expose remains, and, ultimately, this is bad news for writers. If Ferrante writes convincingly about growing up in Naples, how does it matter whether she actually did grow up there, or not? What drives this demand for authors to verify the factual truth of their fiction, as if that is only way it and they can be trusted?

Ferrante writes about women, and because her novels are set during her own lifetime, the belief has arisen that her works are autobiographical. Accompanying this is a whiff of derision, as if the novels are somehow less worthy as fiction and even that they were probably easier to write, if they are based on her life. It seems now that Ferrante knew this was possible: that the deconstruction of the creative act—tearing the butterfly’s wings—was likely and even inevitable, and she gambled that anonymity would protect her. Initially, I would have said that Ferrante’s desire for anonymity had only to do with guarding her personal privacy and preventing costly intrusions into her writing time. Now, I believe she was also safeguarding the imaginative act of writing itself.

Whether Elena Ferrante has written a single autobiographical word may be interesting, but it is “immaterial.” In any work of fiction, on any given page, the author is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. Fiction is built on a variety of truths—emotional, psychological, imaginative, factual—and even writing the most unapologetic autobiographical fiction is never as simple as rendering real events in their correct order. Fictional narrative is not documentary, no matter how closely it seems to mirror the author’s own life. When writers use real people in their stories, they change names and genders, or they don’t change them. They remember, borrow, alter, and conjure out of thin air, and then they kill their darlings. Writers notice things, all the time. They can’t turn it off, and so if you ask a writer, “Did this happen?” she probably cannot answer with a simple yes or no. Instead, she might ask you to pick a random page and then, trailing a finger down the text, tell you, “This is something that happened to me, this is something I saw, this I overheard, this happened to a friend, and I made this last bit up.”

When you read a work of fiction, you strike a deal with the writer: you get to knock around inside her skull for a while, but without knowing exactly how much of it is open to you. Whole sections might be closed off; there may be veils, smoke, or mirrors. The writer might be there in plain sight, but then again, that might just be a cardboard cutout standing over there. The only thing the writer owes you in return for your money is a good story well told. If you are interested in how it was constructed and of what, fine, and if the writer thinks it’s interesting to tell you, great. If not, she has already fulfilled her part of the deal, and in return, you get to experience that story as your own imaginative act, independent of her intentions and desires. She cannot tell you how to read it.

When you read a work of fiction, you strike a deal with the writer: you get to knock around inside her skull for a while, but without knowing exactly how much of it is open to you. Whole sections might be closed off; there may be veils, smoke, or mirrors. The writer might be there in plain sight, but then again, that might just be a cardboard cutout standing over there. The only thing the writer owes you in return for your money is a good story well told. If you are interested in how it was constructed and of what, fine, and if the writer thinks it’s interesting to tell you, great. If not, she has already fulfilled her part of the deal, and in return, you get to experience that story as your own imaginative act, independent of her intentions and desires. She cannot tell you how to read it.

As much as I respect and admire Ferrante’s absolutist approach, I am aware that it does not signal the end of dust jacket photos and author websites for me. I am still near the beginning of my career, still poised on the thin end of the wedge, and if I continue to write and publish as I intend, my work and I will come under increasing scrutiny. I know that, sooner rather than later, I will have to answer, “Did this happen?” Falling to Earth, was set in 1925, and, because I clearly was not alive back then, no one has ever asked if it was autobiographical. I realized only months after the book’s release that, although it is not autobiographical, its emotional truths make it the most personally revealing thing I have written. There I was, hiding in plain sight.

To test myself, I carried out a little experiment and did exactly what I’m asking you not to do. Assuming that art is art, and that the same rules apply, I looked up Vincent Van Gogh’s painting “The Yellow House” online, to see if contemporary photographs of the actual building would also pop up. They did. I can report that, yes, the house in the photos is unmistakably the house that Van Gogh painted. After very little digging, I can also tell you that the window at the corner with both shutters open was Gauguin’s bedroom, and that the window to the left, with its shutters closed, was Van Gogh’s; that the café depicted in “Café Terrace at Night” was also nearby, a little out of frame and to the left; and that the yellow house was so damaged by Allied bombing raids in 1944, it had to be demolished. We also know what Van Gogh’s bedroom looked like from the inside, because he painted it three times, and we know that he painted some of his sunflower paintings specifically to decorate Gauguin’s bedroom in the yellow house, to cheer it up before Gauguin moved in.

These are interesting and melancholy things, but knowing them does nothing to prepare you for the physicality of standing in front of the painting itself. In the museum, there is no glass between you and it; you can get alarmingly close. It is lush and so vertiginous you feel yourself in danger of tipping forward and falling into it. The brushstrokes are careful here, agitated there, the paint so thick in places it looks as if it might still be wet. You realize you’re standing as close to it as Van Gogh himself once stood, which only makes it harder to move away and let someone else have a turn. You can buy a print in the gift shop before you leave, but it will be maddeningly inadequate, so you work your way back through to the painting itself to get near those colors and that light one more time.

Before I became a writer, I trained as an art historian, and then as an MFA student, I studied literary criticism. I have stood on the other side of the easel, as it were. I know how to search for context and layers of meaning in books and works of art. I know the rush that comes with insight and revelation. But then I also know that I envy people seeing famous artworks or reading famous books for the first time. I’m on the fence, as you can see, because, clearly, there is fun to be had either way. Some might even say that my nostalgia for the unschooled response is just a luxury byproduct of my academic training, and they might be right. But then I’d be right to warn against taking it too far and making the extraordinary plain. I’d be right to remind you to be unguarded sometimes, and let books and music and paintings land their punches square in your gut.

Let a butterfly land on your hand. You know that it started out life as a caterpillar, something humbler that could only crawl, and yet now it has wings. Wait a moment. Wait, and watch what it will do next.