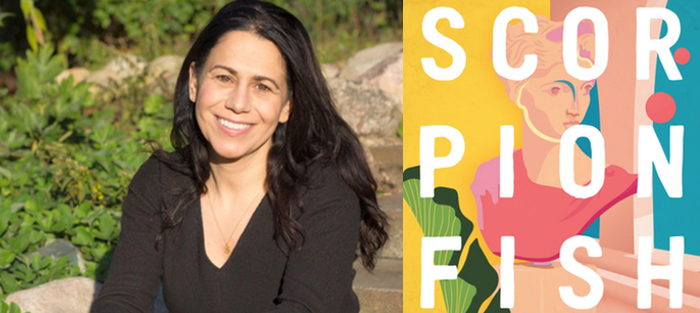

During the coronavirus pandemic, novels have offered me sustained escape into the worlds of others. Natalie Bakopoulos’s new novel, Scorpionfish (Tin House), proved an exemplar—an immersive read in both time and place. Like much of Bakopoulos’s work, Scorpionfish takes place in Greece, centrally Athens. But this novel is not an escapist book. It’s a novel about the politics of space, claiming space, and claiming a self.

It opens with Mira, an American ethnographer whose Greek parents left their native country and settled in the US, returning to Athens from Chicago as she does each summer. But this year, it’s different: her parents have both recently passed. Interwoven with Mira’s story is that of her Athenian neighbor, the Captain, who’s been released from his post at sea and who is currently separated from his wife, the mother of his school-age children. Mira and the Captain are connected through community and family, but their relationship deepens as each negotiates their losses of and emotional distance from those they they’ve loved most.

At the same time, Mira’s artist friend Nefeli triumphs with a major gallery opening just as she retreats from the world—a self-imposed, personally and politically informed exile that serves as the novel’s conscience, with devastating results. Nefeli’s story snuck up on me, and brought me back from the universe of the novel to the lived world with new ways of seeing political engagement as an embodied act. Bakopoulos claims Elena Ferrante as an important influence; others have mentioned Rachel Cusk, and I would add Jane Alison, Siri Hustvedt, and Lily King.

I finished reading Scorpionfish the week before George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. And the conversation I had with Bakopoulos took shape via email as America emerged from shelter-in-place orders into renewed righteous indignation over racial injustice. Nefeli intentionally and indelibly shifts the terms of gender, ethnic, and national relationship dynamics throughout Scorpionfish. As a consequence of the power of this narrative, which dovetailed with the shifts in the social and political atmosphere around us, the author and I moved from a discussion about character, exile, and craft into questions of language and power, and what it means to take up space.

Natalie Bakopoulos is also the author of the novel The Green Shore, and her work has appeared in such places as Ploughshares, Ninth Letter, Tin House, VQR, The Iowa Review, The New York Times, Granta, Glimmer Train, Mississippi Review, MQR, O. Henry Prize Stories, and various other publications. She received her MFA from the University of Michigan, has received fellowships from the Camargo and MacDowell foundations and the Sozopol Fiction Seminars, and was a 2015 Fulbright Fellow in Athens, Greece. She is an assistant professor at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: I’d like to begin with Greece, which is the central setting of your work but a state of mind in your fictional universe as well. You teach in Greece most summers—although I imagine not this year. Could you tell us about how Greece became central to your fiction, and how your time there continues to influence your work?

Natalie Bakopoulos: Greece is my favorite place, the place I feel like my truest self, the most relaxed, the most free. I traveled there several times when I was younger to visit family, but it’s only been in the last fifteen years that I’ve begun to spend time there each year. I grew into my Greek self at the same time I grew into my writer self. So now the two for me are inextricable.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Greece is my favorite place, the place I feel like my truest self, the most relaxed, the most free. I traveled there several times when I was younger to visit family, but it’s only been in the last fifteen years that I’ve begun to spend time there each year. I grew into my Greek self at the same time I grew into my writer self. So now the two for me are inextricable.

This is not to say my relationship with Greece is not fraught. Though my father is from Athens, I didn’t learn Greek as a child—I learned Ukrainian, my mother’s language. I don’t know why my father didn’t teach me Greek. Maybe he was outnumbered, or wanted to be “American.” But this meant that I didn’t begin studying Greek until graduate school. And though now my comprehension on the page and in speech is good, I still have trouble articulating. It’s not that I don’t know how to express something, it’s that I cannot seem to get the voice out. When I have to speak, particularly to people I know, something is blocked, as if I won’t allow myself the fluency. My language lingers in the in-between. I think writing about Greece is a way to find a sort of fluency.

I also find that doing translation—allowing the language of another writer to move through me—has begun to help me feel more comfortable in the language. It’s also a way to become a better writer. When asked about the teaching of creative writing, Javier Marias said: “If I ever had my own creative writing school I would only admit people who could translate. And I would make them do it over and over again.”

When you imagine characters’ worlds and experiences, how much does the specificity of the languages—such as Rami, a multilingual preteen who is native speaker of Arabic and a refugee—shape the way you understand your characters and the choices they make?

This is not my specialty, and I’m sure linguists and sociologists would be able to talk at length about the complexities of your question—whether native language, say, affects our cognitive universe. Maybe our interpretive one, sure. In these pages several years ago, Giota Tachtara examined this topic at length, writing on the different associations she has with words in Greek and English, the way for her the word pezodromio in Greek and “sidewalk” in English have such deeply different connotations.

But I don’t believe that what can be expressed in one language cannot be expressed in another—the way the feelings and ideas are articulated might simply come together differently, or have varieties of cultural weight. Aleksandar Hemon writes in My Parents: An Introduction:

The words might have a different value or interpretive aura, but there is always more than enough overlapping not to dismiss the process of translation, which is essential not only to the project of literature, but to the project of humanity. Yet it can be exceedingly difficult, particularly if the meaning of a word/concept is inscribed in the body.

For instance, Mira’s Greek name is Myrto. But when she moved to Chicago, “Myrto” didn’t fall off the American tongue, and her name morphed to Mira. However, Mira (or, Moira in a closer transliteration) means “fate” in Greek. And while Mira is a common name in other cultures and language—in Slavic languages it means peace, for instance—it’s unlikely you’d meet a Greek with this name. Maybe it’s too weighted, too fraught, too much tempting of fate to name your child fate. But she answers, and feels emotionally connected, to both. So the way her name is used in the novel perhaps says more about how the speaker sees her.

As for Rami, perhaps he’ll be partially shaped through the act of missing home—this of course is tied to language. Spoken Arabic heard in Greece or in Germany, or wherever he finds himself, will have an undeniable pull and association for him. But I was exploring the way that living in Athens, and having community, even if transient, might also complicate his ideas of home and what’s familiar, a trail of concentric homelands, to paraphrase Hemon; an identity where all these factors become interdependent. Rami might be afraid the home he knew no longer exists, but it doesn’t mean he won’t long for it. He accesses all this in a multivalent way: through multiple languages, as he writes, but also through image, visual storytelling. Some writers, even if living in English, say, might choose to write in their first language; others, like Yiyun Li, choose English as their literary language, even if not their native tongue.

Characters in both novels are informed by the social and political context of Greece, and in this second novel, movement back and forth between Greece and the US. In many cases, this informs the choices and circumstances of your characters. Mira, for example, is an academic whose parents raised her in Chicago. You employ deft and subtle explanations of Greek social and political context in exposition, which seem to inform the characters themselves. So how do you see Greek society and politics informing the development of your characters?

There’s no question for me: to say something isn’t political is indeed a political statement. In her introduction to Best American Essays 2018, Roxane Gay astutely notes that to declare one’s writing as apolitical is still a political stance. The bodies we’re in, the bodies we move through the world in, are inextricable from the way we see the world. I’m writing about Greece in a contemporary moment, shaped by two global events: a crisis of capitalism and a crisis of migration. And all the characters are influenced by these things dramatically.

There’s no question for me: to say something isn’t political is indeed a political statement. In her introduction to Best American Essays 2018, Roxane Gay astutely notes that to declare one’s writing as apolitical is still a political stance. The bodies we’re in, the bodies we move through the world in, are inextricable from the way we see the world. I’m writing about Greece in a contemporary moment, shaped by two global events: a crisis of capitalism and a crisis of migration. And all the characters are influenced by these things dramatically.

Obviously when I wrote this novel I was thinking not of the current global crisis but of the one that’s been taking place in Greece over the last few years. Yet the way we’re presented so often with false binaries, as if they were our only choices—right now we’re told it’s either public health or the economy—has always resonated with me. And while all the characters of this novel are deeply political, the character of Nefeli is most deeply so. She’s furious. Not at Greece in particular, but at the entire geopolitical situation. In the context of the global financial crisis, and the refugee crisis (or issues regarding refugee reception, which is I think a better way of thinking about it), Greece has been in the midst of an ever-changing reality. This sort of reality produces a kind of limbo, an uncertainty, a way of being in the world that’s hesitant—particularly when the entire world is watching. And it does act on the body.

I wanted to ask you about Nefeli, in particular. While there are two narrators in Scorpionfish—Mira and the Captain—the narrative arc is a nexus of their stories together with Nefeli’s. How did you decide to render the story through Mira and the Captain’s perspectives, rather than Nefeli’s?

On a structural level, I always saw this book as sort of dialogue, like in Odysseus Elytis’s Maria Nefele poems. She’s his doppelganger, or other self. And though part of me resists the way Maria Nefele is sometimes portrayed as a manic pixie dreamgirl, I was interested in this call-and-response structure for a novel. This was my initial scaffolding, so to speak—and like all scaffolding some of it falls away in the finished project.

Nefeli is a character from my first novel—she was a young student in an island prison camp, a minor character—who never quite left me. She is also, in many ways, inspired by my late aunt. It may have been my desire to better connect with her that helped shape the character of Nefeli—though Nefeli really is a product of my imagination. And though characters are in some ways extensions of ourselves, and though I don’t think you should only attempt to write from points of view within your own experience, I do think you need to ask to what end and why. Is the movement lateral in terms of power, say? Or, to paraphrase Alexander Chee: Why do you want to write from this point of view?

Certainly, there’s a power in first person—to narrate is a claiming of power—but It felt more true for this project to have Nefeli as a beloved person in both characters’ lives. Also, so much of the book is about identity as relational. So while they do not have a first-person point of view, Rami and Nefeli are also telling their stories. For Rami, there’s drawing, and for Nefeli, the visual and the aural. A small part of Rami’s story in Athens intersects with Mira’s, but there are parts of his story that, with her privilege and comfort, she could not possibly completely understand. As an ethnographer, she’s begun to question what she does—is it scholarship or art? Might telling someone’s story be an act of aggression as well as representation? I wanted to gesture to the idea that though he is very dear to Mira and others in the book, Rami has agency as to how he tells his story. That is, some details are just not available to Mira; they are not hers to know, or tell. I’m not sure if I succeeded, but that was my attempt.

Last year, I read Ayşegül Savaş’s brilliant Walking on the Ceiling, which is, among many other things, about storytelling—how by creating one version of events and people we eclipse all the others. Each word, each line in a story eliminates so many other possibilities. The telling of stories has its moral complications.

Last year, I read Ayşegül Savaş’s brilliant Walking on the Ceiling, which is, among many other things, about storytelling—how by creating one version of events and people we eclipse all the others. Each word, each line in a story eliminates so many other possibilities. The telling of stories has its moral complications.

Both narrators in Scorpionfish are in exile—not politically, but emotionally. For example, Mira’s mother was renovating her childhood apartment when she died, and what Mira sees when she returns after her parents’ death calls up the idea that you can never go home again. And then her relationship with her boyfriend, an aspiring politician, falls apart. Throughout the book, the Captain’s relationship is in limbo as well.

Yes, exile is a sort of limbo too, right? I think in some ways all the characters are in limbo. Being in one place but thinking of another, or being between two places, outside definite borders, or in transition. Whereas I think personal nostalgia can be a powerful feeling, to be sure, and right now for instance I feel sick with missing Greece, I have also felt alienated by the kitschy, nationalistic mood of belonging in either Greek American or Ukrainian American communities. Nostalgia as a literary or artistic preoccupation can be too simplistic, boring. On a level of national identity it has a “make America great again” tinge to it, and often forgets that the past is not some fixed point in time. I think for Mira, she’s a bit more removed from the situation in Greece—she’s got the privilege of an American salary and an American passport. For her, she’s shaped mostly by missing Greece, and also by a transnational identity—she has a fully formed life in both places. She doesn’t see Greece through an Instagram filter; neither has she experienced its day-to-day realities.

I was thinking a lot about a certain kind of return narrative, particularly one rooted more in choice or privilege than exile or need. Mira’s return to Greece is in stark contrast to those who’ve come to Greece seeking a better life—whether from Balkan or Eastern European countries or from Nigeria or Pakistan or Syria, say. What are the politics of return? Often “return,” particularly to Greece, is framed in a sort of nostalgic, sentimental way, or a claim based on “blood.” Yet while I do not deny the power of an attachment to place, and I believe that cultural pride can be powerful for marginalized or disenfranchised groups, when the discourse claims a sort of supremacy or superiority, when it uses this rhetoric for exclusion, it’s downright dangerous.

Still. This is not to say that an affinity toward a place does not live in the body. Mira feels alienated by American social structures, but she also has enough security to be able to reject them. And though the streak of social conservatism in Greece, even among those who would not call themselves conservative, drives her crazy, she also finds and appreciates that the notion of family there goes beyond a more nuclear model. There’s a greater sense of the collective. I’m not saying this is fully the case, and I don’t want to make these sorts of culture-as-monolith pronouncements, but for Mira, it is definitely so. She experiences it as more fluid, more inclusive, and this I think surprises her.

Finally, though, I was thinking less in terms of exile or migration and more in terms of reception. Not how and why people are moving—though of course those things are important—but how they are received once they arrive. I love Dina Nayeri’s essay “The Ungrateful Refugee,” where she notes that when she arrived in America, her family’s escape story was repeated again and again, a “salvation story as a talisman, nothing more.” Of course, these stories are important. I don’t mean to disclaim them. But it says something about the audience who only wants to hear them to make themselves feel better about themselves, their lives, maybe even a smugness toward their experience as a superior one.

Did you work with the tensions between exile and community in advancing character and plot, and by extension narrative arc?

I love that idea: exile on a craft level. The problem of exile, after all, is the problem of time and space. Which is, in many ways, also the concern of fiction. In his essay “Exiles,” Roberto Bolaño writes that “All literature carries exile within it.”

I love that idea: exile on a craft level. The problem of exile, after all, is the problem of time and space. Which is, in many ways, also the concern of fiction. In his essay “Exiles,” Roberto Bolaño writes that “All literature carries exile within it.”

That is to say, when we create a story, perhaps we are entering a time and space that has not before existed. Even if we are writing completely from memory, even if we are narrating events that are true, we are still creating something new: an experience for the reader. Plus, we are still subverting time by this reentry. Where do we begin, in time and space? Where do we end? And because I think identity and craft are inextricable, the way a story is told is as related to identity as it is to craft.

I think one of the feelings exile produces is a sense of in-between—you’re both within a place and somehow distinctly outside its borders. Also, a doubleness. It’s how I began maybe not the narrative arc, but at least the narrative strategy. Two narrators who are sort of doubles. And I was thinking of many of the characters as doubles, in many sorts of permutations. All the characters in this book are in states of limbo that at times feel excruciating in their uncertainty but also strangely familiar.

Yet, body as a site of memory and community is a central motif through the narrative as well.

Yes! That’s a really smart, thoughtful observation, thank you. On one level, I was simply thinking of the way memory lives in the body: half experience and half dream. Sometimes in very literal ways; Mira walks into spaces in Athens and her body remembers to get off at the third floor, say, or the way a rooftop can bring back such a rush of memory that it collapses time and space.

But I was also thinking about identity, politics, and the body. About the sorts of relationships that are socially sanctioned and those that are not—we’re suspicious of the childless woman, as though she’s gotten away with something at best, or that she’s deeply damaged at worst. I find this in both the States and in Greece: the former here and the latter there. I wanted to put Mira at the age that, yes, she might still be able to have a child—at least the way others might perceive her—but it’s not something she’s thinking of. If it had weighed on her in her thirties, she doesn’t show any of that now. People still comment that she has time, as if she’s worrying about it, or they think she’s simply chosen her career. It’s far more complicated than that, for anyone. Nefeli, too, as a queer woman who’s spent her life in Greece, has always felt outside its borders—though while she’s angry about it she’s a bit inured to it as well. She’s an internationally recognized artist but she’s never wanted to be anywhere but in Athens. It’s her own way of asserting that she, and her way of being in the world, had every right to be there.

Deborah Levy writes in The Cost of Living: “When a woman has to find a new way of living and breaks from the societal story that has erased her name, she is expected to be viciously self-hating, crazed with suffering, tearful with remorse.” My god, this is so true. Mira and Nefeli are angry, sure—my God who isn’t?—and have a lot of grief, but that’s human. Yet I didn’t want them to be self-hating or apologetic about who they are or the paths they’ve chosen, even though they sometimes see the world asking them to be.

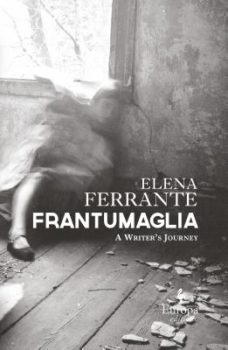

In speaking about tensions between exile and community and the body, I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about the influence of Elena Ferrante before we conclude. You quote a passage from Frantumaglia as the epigraph, in part: “Our entire body, like it or not, enacts a stunning resurrection of the dead.” How do you see her influencing your work?

This line stood out to me because I was thinking so much about memory and the body and identity as relational, collective. Later in that passage Ferrante notes: “We are a crowd of others.” That really stood out to me. A crowd of others. Our stories interconnect, and the act of telling a story is also a way of shaping it.

This line stood out to me because I was thinking so much about memory and the body and identity as relational, collective. Later in that passage Ferrante notes: “We are a crowd of others.” That really stood out to me. A crowd of others. Our stories interconnect, and the act of telling a story is also a way of shaping it.

The story also changes based on the listener. And so this line has always felt like a commentary on writing, too: my writing is shaped by a crowd of others. I know some writers don’t like to read novels, particularly contemporary ones, when they’re drafting, but I welcome the feeling of being in conversation with the writers I’m reading while I write. For this novel, some of those authors were Rabih Alameddine, Aminatta Forna, Katie Kitamura, Stacey D’Erasmo, Amanda Michalopoulou, Jesmyn Ward, Annie Ernaux, Guadalupe Nettel, Mohsin Hamid, Natalia Ginzburg, W.G. Sebald, Alejandro Zambra, Rachel Cusk, Javier Marias, Zadie Smith, Valeria Luiselli, and many more. Though Elena Ferrante was definitely part of that “crowd of others.”

The first Ferrante I read was Days of Abandonment. I was deeply moved by it—the articulation of anger, the focus on the body. Then I went on to the Neapolitan novels, and so on. I love the way Ferrante uses writing, particularly in this quartet, as an assertion of the self. Lenù is writing to keep herself, and Lila, alive. But there’s a bit of co-opting involved—whose stories belong to whom? Who has a right to tell them

Something that really stands out to me in Ferrante’s work is the way the patriarchy, and injustice, and abuse, affects the body, weighs on it, the way we absorb it—but of course this is not exclusive to Ferrante. I was thinking about this particularly in the character of Nefeli, for whom living and making art are inextricable. She absorbs the kinetic energy of her work, like a superhero, and feeds it back in. Often we say women of a certain age become invisible, but I think it’s that we want them to disappear. Don’t wear this, don’t do that. What use do we have for a body that is not an object of a gaze, or that doesn’t look Instagrammed? Nefeli, who already exists outside of more socially conservative structures, finds not only solace and power in art, but also a way of asserting a right to take up space. She does it literally—through a public art installation—but I hope also figuratively as well.

I’m digressing a bit, I know, but one of my preoccupations as a writer has been about the right to space, and different ways of claiming or asserting it. Since completing this novel, much has changed in Athens under the new government, which closed the squats in the center of Athens last fall. Like the fictional one in the novel, these squats, as they are referred to, housed many refugee families, provided language classes, allowed the children to be enrolled in the neighborhood schools. Then in September, the families were suddenly evicted, sent to a tent city camp in Corinth, fifty miles from Athens. Now they are no longer seen, they no longer “take up space”—as if their visibility, to the government, was a threat. All this relates to how issues of refugee reception are handled, by Greece but also by Europe and beyond. There are many humanitarian organizations in Greece providing help, legal counsel, translation and interpreting services, education, and so on to those seeking asylum, refugee status, and so forth—many of these are run by refugees or immigrants themselves, and artists and activists and “solidarians,” a strong network of solidarity.

Protests, as we’re seeing here in U.S., are also about an occupation of space, and I’ve been interested in the language we use to talk about it. The coded nature of the word “riot,” historically, is clear, but even the idea of the qualifier of “peaceful” before protest, as innocuous as it sounds, has coded assumptions and undertones. Whose peace? We mean “nonviolent” but who are we charging with the goal of nonviolence? The use of peaceful in this context doesn’t necessarily only mean nonviolent, but also obedient, orderly, tolerating rather than supporting. Okay, you can protest but not too much. You can grieve but not too much. Don’t get out of control, don’t make people uncomfortable. Don’t be disruptive. Protests, like strikes, are meant to be disruptive; that’s the point. They’re acts of civil disobedience, after all, not obedience. “To protest” in Greek is linked to the word that means “to witness.” Protests are not only a taking up of space, of occupying. They’re a response to collective violence or injustice, and more important, a witnessing. And a call for others to witness as well.