The Recognitions

My mother’s book club meets monthly. Books selected for the club live a familiar life cycle around her house: they are purchased at Portland’s Broadway Books, brought home, and placed directly on the end table at the left side of the living room sofa. The books lie on this table waiting for my mother to read from them for twenty minutes or an hour after dinner until in a few weeks they are finished and replaced with the following month’s selection. A finished book is buried on a basement shelf among stacks of previously discarded tomes. Eat, Pray, Love is there, alongside The Road. The Towers of Trebizond is next to Three Junes. Zadie Smith is there twice: White Teeth and On Beauty. One book per month, bought, read, discarded. It’s been this way for years.

My mother’s book club meets monthly. Books selected for the club live a familiar life cycle around her house: they are purchased at Portland’s Broadway Books, brought home, and placed directly on the end table at the left side of the living room sofa. The books lie on this table waiting for my mother to read from them for twenty minutes or an hour after dinner until in a few weeks they are finished and replaced with the following month’s selection. A finished book is buried on a basement shelf among stacks of previously discarded tomes. Eat, Pray, Love is there, alongside The Road. The Towers of Trebizond is next to Three Junes. Zadie Smith is there twice: White Teeth and On Beauty. One book per month, bought, read, discarded. It’s been this way for years.

But in 2002 the cycle was disrupted. Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections refused to die. The book, like its prede- and successors, was bought and read after dinner. But when it came time to make room for the next book and retire to the basement, it clung to the end table. For two years, subsequent books were purchased, placed atop The Corrections, read, and disposed, while Franzen’s book remained. The Corrections’ presence was so entrenched in the look of the house it was as if a piece of furniture—yet a piece that could never be taken for granted; its orange and white writing screamed out across the room to all within eyeshot.

The book might still be on my mother’s table had I not removed it in the summer of 2004. Earlier that summer I’d been exploring the bookstore Cannon Beach Book Company when I picked up a collection of essays called How to Be Alone. I did not immediately connect the author of this book with that of The Corrections. What did strike me about the book was that its cover picture of readers milling around a bookstore was the same scene I was standing in. In fact, the bookstore pictured—Three Lives and Company, in New York—had more than books in common with the store I was in: the same light wood shelves around the perimeter, same prominent display tables, even the same view from where I was standing and from where Greg Martin shot the cover photo, of the back of the store. It was only after noting these similarities and smiling a little at the title—an ironic reference, I imagined, to a connection among readers1 —that I read the note on the bottom of the cover and realized that this book was by the writer from my mother’s end table.

And as with the books from my mother’s club, I bought, read, and eventually stuck How to Be Alone on a shelf somewhere, but not before deciding to borrow my mother’s The Corrections.

I read the bulk of The Corrections on a roadtrip to visit my wife’s brother in Iowa City. As I immersed myself in the book, we were moving deeper into the heart of the Midwest, and closer literally and figuratively to the setting for St. Jude, the fictional suburb of St. Louis where The Corrections is largely set. The world I saw outside the car window reverberated with Franzen’s words and magnified their urgency.

When we pulled into Iowa City nine months later for our next visit, my brother-in-law, an English graduate student, informed us that we had plans for the evening: Jonathan Franzen would be reading some of his new work on campus. We would attend.

On the walk over to the reading the graduate students in our group were discussing The Corrections. One asked me, an outsider, if I’d read it. I said I had, and he asked if I thought Franzen would address the “Oprah thing.” I couldn’t quite remember what that was. It sounded familiar; maybe it was discussed in one of his essays. I couldn’t recall. We were coming up on the lecture hall just then, so he summarized very quickly: The Corrections had been chosen for Oprah’s Book Club. Franzen had hesitated, saying he wasn’t sure if that was how he wanted people to encounter his work. Many people now disparaged him.

On the walk over to the reading the graduate students in our group were discussing The Corrections. One asked me, an outsider, if I’d read it. I said I had, and he asked if I thought Franzen would address the “Oprah thing.” I couldn’t quite remember what that was. It sounded familiar; maybe it was discussed in one of his essays. I couldn’t recall. We were coming up on the lecture hall just then, so he summarized very quickly: The Corrections had been chosen for Oprah’s Book Club. Franzen had hesitated, saying he wasn’t sure if that was how he wanted people to encounter his work. Many people now disparaged him.

With this in mind, I watched as Franzen walked to the podium in his black jeans and white button shirt, carrying a stack of papers. He seemed a bit distant. Was this arrogance? As he read from an essay that he was working on, “My Bird Problem,”2 I was awed by the seeming effortlessness of his prose. Maybe he was a genius. Maybe he deserved his arrogance. Or maybe he wasn’t arrogant, just self-conscious and self-protecting. My thoughts about Franzen the person—no, about Franzen the personality—began to supplant my thoughts about Franzen the author. And in this, I would discover, I was not alone.

But it would be years until (during the research for this essay) I started to understand the relative magnitude of the “Oprah thing.” In the week after the Iowa City reading I had an end-of-the-year presentation to prepare for my AmeriCorps program. Recalling “My Bird Problem,” I decided to take my first real stab at writing and put together an essay modeled on Franzen’s facile movement between, sometimes among, narratives, which I would read at the event. The completed essay was an ambitious, and probably incoherent, attempt to sum up the year of community service, make a series of insightful cultural criticisms, be hilarious, and acknowledge Franzen’s influence on the writing of the essay. The only memorable scene from my reading was a bizarre stunt wherein I enlisted a co-worker to throw into the audience copies of The Corrections that I had rounded up at local used bookstores when I got to the part about Franzen. Exactly why I did this, or what I intended it to mean, I’m not sure, but one thing was clear: The Corrections had my attention.

The Genesis

For anyone sitting in the audience at that reading, catching or dodging flying words, the proximate source of the book was clear—it had found its way into my life, and I had found its way into theirs—but, I wondered, where did The Corrections really come from?

For anyone sitting in the audience at that reading, catching or dodging flying words, the proximate source of the book was clear—it had found its way into my life, and I had found its way into theirs—but, I wondered, where did The Corrections really come from?

Jonathan Franzen’s first novel, The Twenty-Seventh City, was published in 1988; his second, Strong Motion, in 1992. Both books were critical successes, and neither made much commercial impact.

When he started his third novel in the early ‘90s, he thought he was going to write another similar novel with similar ease. But he found himself bored and struggling. Franzen describes a long, painful process before he decided to shift the story to some of the minor characters, the Lambert family, whom he found more interesting to write about than the original main characters. Eventually, when he dropped the original story altogether, and focused on writing an “old-fashioned family novel” about the Lamberts, he was able to get going on his writing. Despite spending the better part of a decade on the book, the writing of the final version took place in a fairly brief period in 2000. Readers of the work in progress lauded it extravagantly; excerpts were published in the New Yorker and January Magazine.

Franzen’s girlfriend, Kathryn Chetkovich, provides an account of the time period surrounding the publication of The Corrections in her essay, “Envy”3:

In the months it took me to produce a drifty fifteen-page story about the end of a marriage, a short play about a woman who sleeps with her best friend’s husband, and seventy pages of a screenplay that had the desperate signs of “learning experience” written all over it, he piled up several hundred pages of his new novel.

It was, alas, good. My own reading told me this, but I had independent verification as well—because as sections were finished they flew almost immediately into print, and just as immediately the phone would begin to ring with congratulatory messages, comparisons to dead writers and to living writers whose reputations were so established they might as well be dead….

When his novel was done, the man handed it in, and his editor called every hundred pages or so to say he was loving it, then called to say he was cutting the check, and finally called to say he wanted to take the man and me out for a celebratory dinner….

Over the next several months, what had at first seemed like a pathologically extreme anticipation of the man’s success on my part began to look like nothing more than a reasonable prediction. Advance copies of his book were released, and suddenly he was being interviewed, photographed, written and talked about by, it seemed, everyone. Clearly his book was on its way to becoming not a book but the book, and every day seemed to bring new evidence that he was on his way to becoming that rare thing, a writer whom people (not just other writers) have heard of.

So much for the logistics of the writing. The content of a book this well received bears some consideration. Whereas Franzen’s first two novels were more plot-driven, straightforward approaches to engaging with socially interesting topics, The Corrections is a character-driven social novel—the kind of novel, which Franzen had recently feared could not still be written.

His fear was prominently announced in “Perchance to Dream,” an essay published in Harper’s in 1996, which subsequently became known, like Tom Wolfe’s “Stalking The Billion-Footed Beast” before it, as the “Harper’s Essay.” The essay was rewritten as “Why Bother?” and included as a chapter in How to Be Alone. In it Franzen addresses his crisis of faith with regard to the novel in the commercially driven and visual media-centric ‘90s.

The story Franzen tells about his disenchantment with the state of the novel and fear of the death of the social novel follows Philip Roth’s “Writing American Fiction” lead. In Roth’s words: “The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.” In Franzen’s: “We live in a tyranny of the literal.” He goes on to add this pithy summation of the irrelevancy of novelists: “Today’s Baudelaires are hip-hop artists.”

In addition to the tyranny of the literal, the fragmentation of the larger culture concerns Franzen in this essay. As technology continues to fracture communities through the convenience of self-constructed isolated bubbles of personal control, and virtual communities are entered into (and can be quit) on the basis of consumer transactions—is this community satisfying me, constantly satisfying me?—what still connects the personal to the social? “It’s possible that the American experience has become so sprawling and diffracted that no single ‘social novel,’ a la Dickens or Stendhal, can ever hope to mirror it; perhaps ten novels from ten different cultural perspectives are required now.” It is not surprising then that his third novel was floundering. As he describes:

I was paralyzed with the third book. I was torturing the story, stretching it to accommodate ever more of those things-in-the-world that impinge on the enterprise of fiction writing. The work of transparency and beauty and obliqueness that I wanted to write was getting bloated with issues … Panic grows in the gap between the increasing length of the project and the shrinking time increments of cultural change: How to design a craft that can float on history for as long as it takes to built it? The novelist has more and more to say to readers who have less and less time to read: Where to find the energy to engage with a culture in crisis when the crisis consists in the impossibility of engaging with culture? These were unhappy days. I began to think that there was something wrong with the whole model of the novel as a form of “cultural engagement.”

Franzen credits Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters with reinvigorating his faith in the ability of the novel to still connect the personal and the social. Fox’s book reminded him that he wasn’t alone in the world. Fox was asking the same questions he was: “And did the distress I was feeling derive from some internal sickness of the soul, or was it imposed on me by the sickness of society?” Franzen the reader learned that fiction could still connect people. Franzen the writer learned that he could write about the culture without doing so explicitly and therefore begging for irrelevance, by doing so through writing about what he loved.

At the heart of my despair about the novel had been a conflict between a feeling that I should Address the Culture and Bring News to the Mainstream, and my desire to write about the things closest to me, to lose myself in the characters and locales I loved. Writing, and reading too, had become a grim duty, and considering the poor pay, there is seriously no point in doing either if you’re not having fun. As soon as I jettisoned my perceived obligation to the chimerical mainstream, my third book began to move again. I’m amazed, now, that I’d trusted myself so little for so long, that I’d felt such a crushing imperative to engage explicitly with all the forces impinging on the pleasure of reading and writing: as if, in peopling and arranging my own little alternate world, I could ignore the bigger social picture even if I wanted to.

The above italics are mine. The seeming obviousness of this statement is testament to its truth, but in order for the unignored social picture to be very broad, The Corrections must cover a lot of ground: depression, academia, celebrityhood, homosexuality, traditional domestic life, depression, the pharmaceutical industry, stock markets, Eastern Europe, depression, capitalism, and so on. The ambitious breadth of The Corrections, Chad Harbach argues in his n+1 essay “David Foster Wallace!,” owes a debt to David Foster Wallace’s opus, Infinite Jest.

The truth is, Wallace has already written his next big novel—it’s called The Corrections. Jonathan Franzen, during the public rounds that followed the book’s release, described Wallace as his “main rival,” and said that Infinite Jest “got me working, the way that competition will get you working.” These remarks provide more insight into the making of The Corrections than Franzen’s elegant, infamous Harper’s essay, which outlined his partially restored faith in the possibilities of the American social novel, and, not incidentally, hit the newsstands just three months after Infinite Jest (complete with Franzen blurb) hit the shelves. Anyone who has read Franzen’s early work knows that his prose underwent a profound transformation between Strong Motion (1992) and The Corrections (2001). Infinite Jest paved the way for this change.

Of course, Wallace and Franzen were good friends. Wallace blurbed the first edition of The Corrections as follows: “Funny and deeply sad, large-hearted and merciless, The Corrections is a testament to the range and depth of pleasures great fiction affords.” In a few words, this is the core of the book. To see why, a brief summary is required.

Enid Lambert is afraid that the next Christmas might be her husband’s, Alfred’s, last. He suffers from Parkinson’s disease, undiagnosed depression, and oncoming dementia. Enid wants her three adult children to come back from the east coast to St. Jude to celebrate the holiday as a family. None of them want to go home; they’re all very busy with their own lives. But when Alfred has a serious accident, they begin to acknowledge the severity of his situation, and all do come home. It even sort of works out.

If this cursory plot sketch seems inadequate for what I am essentially contending (alongside so many others) is a great book, it is because the plot itself is ancillary to the characters. The novel forsakes what is happening for who it is happening to. The vividly and truly wrought characters are the heart of this book, and the reason why Wallace’s quote makes so much sense. The Lamberts—Enid, Alfred, Gary, Chip, Denise—are all deeply flawed and unhappy people, to the point that the characters’ depressions come to feel like the reader’s. The careful study of the causes and symptoms of the characters’ sufferings brings the reader close enough to understand their sufferings from the inside. It bears repeating: this is a deeply sad book. The Corrections’ saving grace is that for all its sadness, Franzen continually treats the Lamberts with love. So when we come in contact with depression, it’s right next to compassion. We too love the Lamberts. Not because we respect them—some of us will not respect them on any account—but because they’re distinctly human, and we know what they’re going through.

All of which can be seen on the cover of the book.

The Artifact

My judgment of the book by its cover is going to be influenced by my reading of the book as being deeply sad but ultimately life affirming. This process was carried out in the reverse direction when I first saw the book on my mother’s table. It looked sad and serious and boring. Reading the book vindicated two of those three and now influences what else I see in the cover. I’ll flesh this out beginning with the paperback edition that I first read, and then move on to comparisons with the first hardbound edition, an advance reader copy, and a U.K. edition.

The paperback version of The Corrections, published by Picador on August 27, 2002, has a picture of the Lambert family sitting down to a turkey dinner. This is the same picture that debuted on the original hardback version, but I will discuss this appearance first because, for a number of reasons, I consider it the definitive text. Alberto Manguel articulates the first reason in A History of Reading: “One reads a certain edition, a specific copy, recognizable by the roughness or smoothness of its paper, by its scent, by a slight tear on page 72 and a coffee ring on the right-hand corner of the back cover.” It isn’t a coffee ring that distinguishes my copy of The Corrections but an unaccounted-for crease running the length of the front cover and the word gerontocratic, which someone—not my mother, not I—who?—has underlined on page 3 and written out at the top of the same page in an uneven and well-rounded hand.

The paperback version of The Corrections, published by Picador on August 27, 2002, has a picture of the Lambert family sitting down to a turkey dinner. This is the same picture that debuted on the original hardback version, but I will discuss this appearance first because, for a number of reasons, I consider it the definitive text. Alberto Manguel articulates the first reason in A History of Reading: “One reads a certain edition, a specific copy, recognizable by the roughness or smoothness of its paper, by its scent, by a slight tear on page 72 and a coffee ring on the right-hand corner of the back cover.” It isn’t a coffee ring that distinguishes my copy of The Corrections but an unaccounted-for crease running the length of the front cover and the word gerontocratic, which someone—not my mother, not I—who?—has underlined on page 3 and written out at the top of the same page in an uneven and well-rounded hand.

About the picture: from left to right are Chip, Gary, Enid, and Alfred. Of Albert’s suited body, only a triangular segment of his chest is visible. Of Enid, who is holding the turkey platter, we see only the waist of her red dress and her hands with red-painted nails. Gary wears a smile, but his head is cut off at the nose, we cannot see if his eyes match it. Chip’s is the only face we see in full. Denise is altogether absent from the picture. Judging by the ages of Chip and Gary, Denise is possibly unborn. Otherwise it can be assumed she is seated—probably in a highchair—across from Gary, and was cropped out of the frame.

This cover is wonderfully suited to the story. That it to say, it’s dreadful. The scene is a traditional 1950s-style family dinner. It is a square meal for a square family, but the food looks bland and un-nourishing. What’s interesting about Denise’s absence is that as an adult she is a gourmet and celebrity chef, and would never serve such an insipid, uninteresting meal. Continuing this line of theorizing, the other pictorial representations also fit their scriptural counterparts. Alfred and Enid are headless; they don’t see what their lives actually are. Enid is in desperate control of the dinner, as she’s in desperate control of each of her family member’s lives, embodying the value of keeping up appearances above all else. Alfred is only passively engaged with the scene. He waits for his wife to handle this “family activity,” so he can return to his private unhappiness. The suit and tie, which are all that we see of Alfred in the picture, are likewise all that his children ever see of him: a formal, disembodied man. Gary, eager to please and do right, is smiling at  his mother’s efforts. Pictured, he is either a parody of innocence or a son in his mother’s lineage who believes that by doing what’s expected of him, happiness will follow. That Chip is the only character whose eyes are shown is no accident, and that his expression is unimpressed, no accident. Of the three children, it is Chip’s adult life that will be most unapologetically in opposition to his parents’ values.

his mother’s efforts. Pictured, he is either a parody of innocence or a son in his mother’s lineage who believes that by doing what’s expected of him, happiness will follow. That Chip is the only character whose eyes are shown is no accident, and that his expression is unimpressed, no accident. Of the three children, it is Chip’s adult life that will be most unapologetically in opposition to his parents’ values.

All of these revelations about the characters that manifest in the cover photo advance the mood of the book, the sadness that permeates a superficially functioning family life. Moving out from the photo, its effect remains. The title itself, The Corrections, and its slanted appearance conspire to suggest that something (the picture below, one assumes) needs correcting. And the boxy, all-capitalized letters of the title and the author’s name indicate that these “corrections” won’t be made gently. Finally, the only blurb on the front cover: “You will laugh, wince, groan, weep, leave the table and maybe the country, promise never to go home again, and be reminded of why you read serious fiction in the first place,” from the New York Review of Books, assuages no sadness. The banner across the top of the cover boasting The National Book Award is the only promise of redemption: Even if it’s depressing, at least someone thought it was good.

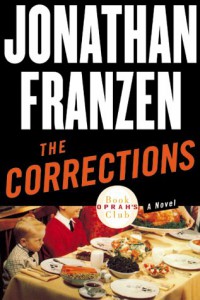

A greater promise of redemption in The Corrections can be found on the cover of the hardback edition. Instead of The National Book Award, this version is endorsed by Oprah’s Book Club. The substitution of her logo for that banner, along with the absence of the above-mentioned blurb, are the only differences between the two covers. But what a difference those differences made. I’ll have more to say about the cultural significance of the brouhaha surrounding the Oprah logo in the next section. For now I want to spend a little more time discussing the publication and appeal of the first edition.

A greater promise of redemption in The Corrections can be found on the cover of the hardback edition. Instead of The National Book Award, this version is endorsed by Oprah’s Book Club. The substitution of her logo for that banner, along with the absence of the above-mentioned blurb, are the only differences between the two covers. But what a difference those differences made. I’ll have more to say about the cultural significance of the brouhaha surrounding the Oprah logo in the next section. For now I want to spend a little more time discussing the publication and appeal of the first edition.

Franzen’s publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, knew that The Corrections was a good book, and expected it to also be a big seller. This confidence was based on, in addition to responses from excerpts printed in magazines, responses the publisher got from the advance reader copy of the book in May 2001. The advance copy was sent out with the following letter from Editor in Chief, Jonathan Galassi, appearing on the first page:

Dear Friends:

It’s a great privilege to send you the bound proofs of Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, THE CORRECTIONS. Ever since I read the manuscript of Jonathan’s amazing first novel, THE TWENTY-SEVENTH CITY, in 1987, I’ve felt he was among the most gifted writers of his generation, and THE CORRECTIONS, I believe, is a masterpiece, a triumphant fulfillment of everything his earlier work led us to expect. Not only is this his best book to date, it’s one of the very best we’ve published in my fifteen years at FSG.

Once you read it, I know you too will be overwhelmed by the poignancy and humor, the tragedy and redemptive power, of the Lamberts’ story.

Enjoy!

Whether or not responses were as laudatory as this letter, Farrar, Straus and Giroux decided on an initial print run of 90,000 to be published on September 4, 2001. When Oprah called to include the book in her club, that number would be increased by 680,000.

With all the anticipation around The Corrections’ publication, there was still a real fear the following week that the September 11 attack would prevent it from having a chance to find its audience. Kathryn Chetkovich reflects on this concern in her essay “Envy,” as does Franzen in “A Word about this Book,” from How to Be Alone: “This was a time when it seemed the voices of self and commerce ought to fall silent—a time when you wanted, in Nick Carraway’s phrase, ‘the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever.’ Nevertheless, business is business. Within forty-eight hours of the calamity, I was giving interviews again.” Franzen’s conflicted feelings about the suspension/continuation of commercial culture foreshadows his more infamous conflict that at the time was only weeks away. Both Franzen’s internal conflict and the later conflict surrounding Oprah were dependent on American readers maintaining an interest in his work in a time when the country was in shock. The Corrections faced the possibility of becoming instantly irrelevant. Franzen discussed this topic on Fresh Air with Terry Gross:

I do feel as if the way it’s read inevitably changes when the tenors of the time change, and it’s of some satisfaction to me that people still seem to find something in it even though the tenor of the times more or less flipped over night. We had been drifting toward a recession, but it was still basically a blissful, isolated time for us all here in the country, and now we’re in a very different place. Evidently, this particular book has managed to bridge those two sides of September 11.

Of course part of The Corrections’ success in bridging the pre- and post-September 11 chasm can be attributed to Oprah proceeding with her on-air endorsement of the book on September 24, but before I turn to Oprah I want to take a final look at The Corrections as object.

Of course part of The Corrections’ success in bridging the pre- and post-September 11 chasm can be attributed to Oprah proceeding with her on-air endorsement of the book on September 24, but before I turn to Oprah I want to take a final look at The Corrections as object.

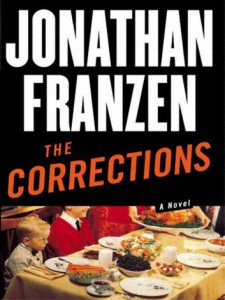

I mentioned earlier that there were a number of reasons that I consider the trade paperback the definitive version of the book. Primarily, this is because it is the edition I first read. Had I read the hardback version first I might favor that version. It appears neater and simpler. If the Oprah logo and The National Book Award banner are allowed to cancel each other out,4 the absence of a front-cover blurb and the larger size of the hardback give it extra space and keep it from feeling crowded like the paperback can. The back covers are consistent in this. The hardback: four blurbs, neatly spaced; a picture of Enid’s waist and elbow. The paperback: a mess combining lists of awards and excerpts from reviews on top; summary, and book and author info on bottom.

But the hardback has shortcomings as well, that reveal, in my mind, the superiority of the paperback. The size of the hardback (9.1 x 6.1 x 1.8 inches), which allows for a nicer view from the front, when experienced in three dimensions can—unlike the paperback (8.2 x 5.4 x 0.9 inches)—intimidate readers and does betray one of the book’s greatest strengths: it is a big book undercover. The mass of the hardback exposes this disguise. I’ll explain what I mean by making a comparison to its rival and alleged inspiration, Infinite Jest. Infinite Jest, even in paperback, is a big, heavy, intimidating book. If you open it up, you will be daunted by the shear mass of words in front of you. If you brave further, you will discover the need for multiple dictionary consultations. And if you happen read the foreword to the Special Tenth Anniversary Edition, you will find Dave Eggers claiming:

But the hardback has shortcomings as well, that reveal, in my mind, the superiority of the paperback. The size of the hardback (9.1 x 6.1 x 1.8 inches), which allows for a nicer view from the front, when experienced in three dimensions can—unlike the paperback (8.2 x 5.4 x 0.9 inches)—intimidate readers and does betray one of the book’s greatest strengths: it is a big book undercover. The mass of the hardback exposes this disguise. I’ll explain what I mean by making a comparison to its rival and alleged inspiration, Infinite Jest. Infinite Jest, even in paperback, is a big, heavy, intimidating book. If you open it up, you will be daunted by the shear mass of words in front of you. If you brave further, you will discover the need for multiple dictionary consultations. And if you happen read the foreword to the Special Tenth Anniversary Edition, you will find Dave Eggers claiming:

When you exit these pages after that month of reading, you are a better person. It’s insane, but also hard to deny. Your brain is stronger because it’s been given a monthlong workout, and more importantly, you heart is sturdier, for there has scarcely been written a more moving account of desperation, depression, addiction, generational stasis and yearning, or the obsession with human expectations, with artistic and athletic and intellectual possibility. The themes here are big, and the emotions (guarded as they are) are very real, and the cumulative effect of the book is, you could say, seismic. It would be very unlikely that you would find a reader who, after finishing the book, would shrug and say, “Eh.”

What’s interesting about this passage is that with only minor changes it can be applied accurately to The Corrections. The key difference is that The Corrections makes for much easier reading than Infinite Jest. The same big themes, big emotions are conveyed, but with subterfuge; a big, healthy dose that goes down easy. As an unassuming paperback, The Corrections allows its readers the same indulgence as the inviting prose: that they’re not working hard.

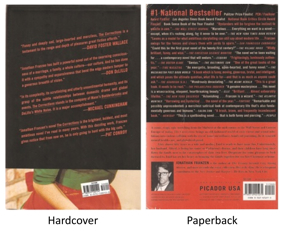

Another flaw with the hardback edition appears on the spine, where at the top appears a picture of Alfred wearing the same suit and tie as on the cover. There are two problems here. First, Alfred is not the most important character in the book. If there is one, it is either Enid or Chip. Second, looking at Alfred’s chin in the picture, it is possible that he is smiling. The Alfred we encounter in the book suffers from depression for most of his adult life. That he would be smiling on the book’s spine seems counter to his character. In fact, looking at the advance reader copy, we do see a smiling Alfred. The jovial picture was wisely altered, but it was not until the paperback edition that the designers made the further improvement of putting Chip on the spine. Chip is shown in the same pose we see on the cover—a picture much more representative of the book. The other obvious change on the spine from hardback to paperback is the switch in emphasis from the author’s name to the book’s. This change may have been in response to the bad publicity Franzen received after the blow-up with Oprah, or to the acclaim and awards the book won,5 though these two are nearly impossible to separate.

Another flaw with the hardback edition appears on the spine, where at the top appears a picture of Alfred wearing the same suit and tie as on the cover. There are two problems here. First, Alfred is not the most important character in the book. If there is one, it is either Enid or Chip. Second, looking at Alfred’s chin in the picture, it is possible that he is smiling. The Alfred we encounter in the book suffers from depression for most of his adult life. That he would be smiling on the book’s spine seems counter to his character. In fact, looking at the advance reader copy, we do see a smiling Alfred. The jovial picture was wisely altered, but it was not until the paperback edition that the designers made the further improvement of putting Chip on the spine. Chip is shown in the same pose we see on the cover—a picture much more representative of the book. The other obvious change on the spine from hardback to paperback is the switch in emphasis from the author’s name to the book’s. This change may have been in response to the bad publicity Franzen received after the blow-up with Oprah, or to the acclaim and awards the book won,5 though these two are nearly impossible to separate.

The final criticism I have of the hardback version takes me back to the cover, and back to Oprah. Her logo is such a powerful cultural symbol that it simply has too great an impact on a person’s reading of the book. I was lucky that when I read The Corrections I was all but unaware of the controversy surrounding it. Franzen does discuss it in How to Be Alone, but he treats it so lightly that it’s hard to know from it what a big deal it was. The paperback allows for a less influenced reading.

These differences that I’ve discussed are noticeable because they are so few. All of the American versions of The Corrections are remarkably similar in appearance. To see the book treated in a significantly different way we must turn to foreign editions. As a case study, I will look at a U.K. edition, which was published by Harper Perennial in 2007.

On the cover is a cruise ship with a man peering over the bow. This image draws on an important scene from the book, but there is no indication in the picture that this man is Alfred or that he will fall off, almost kill himself, and force his family to finally see how far he has deteriorated. Instead, the cover implies a whimsical journey and a pleasant sunrise. The text on the page mentions not the awards the book won, but its bestseller status; the blurb evokes the book’s readability, humor, and generosity, but not its sadness. The back cover rectifies each of the front’s shortcomings, but it is not enough to save the cover from misrepresenting the book’s contents. What’s striking about the UK edition failing to capture the mood of the book is that mood is of fundamental importance to this book. My mother’s reading demonstrates this.

On the cover is a cruise ship with a man peering over the bow. This image draws on an important scene from the book, but there is no indication in the picture that this man is Alfred or that he will fall off, almost kill himself, and force his family to finally see how far he has deteriorated. Instead, the cover implies a whimsical journey and a pleasant sunrise. The text on the page mentions not the awards the book won, but its bestseller status; the blurb evokes the book’s readability, humor, and generosity, but not its sadness. The back cover rectifies each of the front’s shortcomings, but it is not enough to save the cover from misrepresenting the book’s contents. What’s striking about the UK edition failing to capture the mood of the book is that mood is of fundamental importance to this book. My mother’s reading demonstrates this.

When I borrowed her copy in the summer of 2004, I first asked her opinion of it. She told me that it was “excellent,” and attested that “the dinner scene sticks with you.” As I was reading it in Iowa I came to her bookmark about two-thirds of the way through the book. I later asked her if she ever finished it. She said that she had not. This is why it never made it from her end table to the basement bookshelf. While she had found it “excellent,” she did not feel it necessary to see how the story ended. In my terms, the mood of The Corrections trumps its plot.

This sadness that I keep referring to is not exhaustive of the mood. Every review and blurb I’ve quoted has also mentioned the book’s humor. I’ll gladly admit it’s there—how about when Chip tries to play it cool with his agent’s husband and conceal the fish stuffed down his pants? There is hope too—particularly for Chip, who seems to end up happy, and Enid, who is described in the last sentence of the book as follows: “She was seventy-five years old and she was going to make some changes in her life.” But the question that seemed to throw some people, including Franzen, was, Did those kinds of tempered corrections constitute the redemption that Oprah Book Club readers might expect, or was it too edgy, too high-brow?

To Be Continued …

Read the conclusion of Scott Parker’s essay, in which he considers the tension between art and commerce, and why The Corrections remains an important work, perhaps because Franzen is the kind of writer who’d rather his books speak for themselves.

Endnotes

A suspicion partially confirmed by Franzen in an interview with Charlie Rose: “People are lonely. You’re alone with yourself. And novels are about connecting across the great gaps from the rather lonely center of one person to the rather lonely center of another.”

Later to be included as the concluding chapter in his memoir, Discomfort Zone.

Though Chetkovich’s essay “Envy” was originally published by Granta in Issue 82 (summer 2003), you can read an extract from the piece on the Guardian/Observer site.

Part of the agreement that FSG made with Oprah, at Franzen’s request, was that not all of the books would have the Oprah logo on the cover. This cover (pictured, but not seen personally) wins in appearance by my accounting.

In addition to The National Book Award, The Corrections was also the fiction winner for ALA Notable Books, and a nominee for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the L.A. Times Book Prize, the Book Sense Book of the Year Award, and the PEN/Faulkner Award.

Note: To return to essay after reading an endnote, press the “back” button in your browser.