I’ve always loved the connotations of the word workshop. There’s refinement in a seminar and hierarchy in a master-class, but a workshop brings to mind sawdust and power tools. A bunch of unshaven people in greasy jumpsuits. To call a class a workshop implies that we’ll replace or reinforce theoretical lessons with the practical work of making and fixing tangible objects: the machines that texts are.

At advanced levels especially, workshop courses tend to proceed manuscript by manuscript, like a fix-it shop where we poke around under the hood, trying to understand how this particular engine works and what can be done to make it run better.

For people who love workshops, like me, this problem-solving methodology is not just instructive, it’s fun. Stimulating. In fact, part of what made me sure I wanted to be a writer—and a writing teacher—was the pleasure I experienced in workshop, helping my peers and students solve those problems.

But a funny thing happened after I spent a few years loving life in writing workshops. With each semester my work grew more careful, more conventional, more narrowly proscribed. My weirdest, most experimental work came and went before I’d finished my first semester of grad school. Back then I would have said my writing was becoming more refined, and that’s certainly true. But in retrospect I also think that my fears were setting in, eroding the courage borne of naïveté that I had enjoyed as a younger writer.

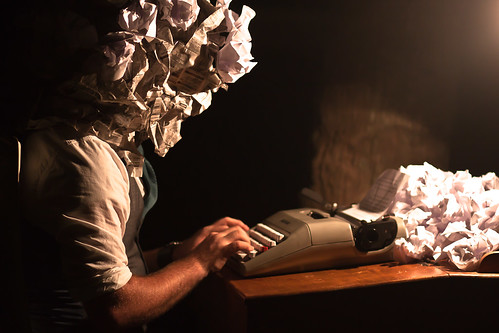

I had genuinely masterful teachers, and they ran their workshops with respect, imagination, generosity, and vast expertise. I honestly don’t think they could have done a better job. And yet by the time I graduated, whenever I sat down to write a sentence, my head was instantly flooded with the voices of my workshop peers and teachers. The biggest thing I learned in grad school, it seemed, was a powerful, paralyzing sense of all the mistakes I was about to make in my next paragraph. Ideas for stories kept coming and coming, but when I tried to put them on paper I didn’t just dry up—I experienced genuine panic. This lasted for years.

The worst part was, I could hardly admit it to anyone. The very notion of writer’s block is often treated, in serious academic workshops, as a weakness or lack of discipline experienced only by hacks and amateurs. And maybe it is. But something tells me it strikes the best and worst of us. And if writers don’t learn to overcome the anxieties that stop them from writing, then every other skill we teach them will be for naught.

**

Conversations about process, self-motivation, and confidence sometimes crop up in private student-teacher conversations, but they rarely find an official place in the curriculum of advanced academic workshops. A lot of us—students included—consider those touchy-feely, self-expression, free-your-imagination conversations and exercises to be well beneath us. We relegate them to the domain of adult-education workshops and Write Your Novel in 30 Days! books, and to the self-help land of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way franchise.

In college I took a one-day workshop with a National Book Award-winning visiting writer who asked if we could take a moment at the beginning of class to meditate. She rang a bell. After she closed her eyes, we all shot hysterical glances at one another and tried to keep straight faces. And, I’m ashamed to say, we pretty much wrote off everything she said for the next hour as the rantings of a weird hippie.

Some of my peers later studied with a wonderful writer and teacher who asked them, on the first night of workshop, to map out their story ideas in crayon on big sheets of paper. They left the classroom incensed. “I didn’t go to grad school,” one student said, “to draw pictures.” Perhaps she’d been trying to release them from their normal approach to story creating. Who knows. But that professor spent the rest of the semester trying, and never quite succeeding, to rebuild her credibility, her authority.

In “serious” academic workshops, the actual act of writing occurs at home, in secret—or it doesn’t occur at all. Everyone jokingly acknowledges that “Of course you’ll spend the first few days after workshop or the first several months after grad school feeling overwhelmed, defeated, reluctant to write. That’s just how it goes.” The tough ones will find a way back to their computers and notebooks, and the rest, well… who knows what happens to them? The rare student who works up the nerve to actually ask how to overcome writer’s block risks shame, risks being written off. And anyway, the usual response boils down to little more than, “Sit at your desk and just do it.”

Despite all our declarations to students that masterful texts result from rigorous revision and don’t just fall from the sky, academic workshops imply that first drafts, at least, fall from the sky. Beyond the stage of “Intro to Creative Writing,” we spend very little time helping students develop the skills to generate those first drafts.

I suspect this is partly because the pedagogy associated with overcoming doubt and generating raw material is tainted by its associations with self-help, therapy, nurturing, self-expression, and spirituality. I sense, too, that each of these areas is tinged with connotations of femininity. I know part of what makes me afraid to engage with those topics in workshop is my reluctance to play the nurturing female role. To teach these psychological, or yes, even spiritual skills is to risk losing our credibility as serious writers and professors. But if we continue to cede this territory to “unserious” workshops and, out of fear, convention, or prejudice, avoid teaching the psychological strategies required of life-long writers, I think our students miss out on some skills that are essential to the success, survival and sanity of any writer.

**

During my painful, frightened, depressed years as a blocked writer, I ended up spending quite a bit of time watching TV. The Tennis Channel, to be specific. Watching the two to five hours of a tennis match, you can actually see and hear (as you can’t in most sports) the tremendous physical and emotional highs and lows that players go through. They are unhidden by helmets or pads, and the downtime between points and games allows for intense close-ups of each player as she strategizes, scolds herself, or simply melts down. Most importantly: each player is alone. Coaching of any kind during a match is prohibited in most pro tournaments. Whatever strategy, motivation, support, or composure a coach in any other sport might offer has to come, in tennis, from within the player herself.

In other words, the coach’s job involves teaching players to develop the inner resources to overcome fear and frustration, to maintain confidence, and to keep a clear, focused mind under extraordinarily challenging circumstances.

When a player fails at this, when a wildly talented, well-trained player loses his confidence or the rhythm of his serve, everyone watching can see it, plain as day. The coach grits his teeth in impossible frustration, and spectators scream advice and encouragement, but the player has already lost, in his head, and hears none of this. Players who truly lose their confidence, for good, stumble from loss to loss, all their talent and training and a lifetime of grueling work made meaningless because their brains have gotten in the way. Head cases, people call them. Every sport has them, every fan mourns them. Sportscasters whistle under their breath and suggest sports psychologists, a change of coaches, a change of racquets, a change of anything.

Sometimes when I watch a player I love lose a tough, pivotal match I think, “Thank God as writers the game never ends; there is always the chance to revise something and get it right.” The story will wait until we get our heads on straight—or so we like to think.

Other times, in periods of frustration or boredom with my writing, I think, “What a great thing it would be to have the game just be over and done with. Take a shower, go to bed, start over the next day with a clean slate. No manuscript hanging over your head, unfinished, unfinished, unfinished.”

A player might review a lost match on game tape or in her bad dreams for years to come, but she cannot actually revise it. The psychological make-up of the successful athlete has to include the ability to put the last match behind her. To learn from it and drop it and move forward.

In the academic, manuscript-based workshop, we tend to train students in a different psychology: revise, revise, and then revise some more. As the writer and pedagogy theorist Anna Leahy writes in a description of her teaching methods, “Most importantly, I treat everyone’s work as unfinished, always.”1 The typical methodology of the academic workshop puts the manuscript before the writer; people talk about “what the text is trying to do” and sometimes don’t even look at the writer when they offer their feedback. Sometimes it seems that the serious workshop serves to perfect texts, not develop writers. Or, it serves texts directly, and writers only indirectly. We tend to disregard the fact that some manuscripts aren’t worth perfecting and should perhaps be chalked up as a loss so the writer can freely move on to the next match.

If the primary focus of academic workshops is to highlight what isn’t working in the manuscript, and through constant emphasis on revision imply that the work is never done, may never be done, after a few years of taking workshops students must end up feeling that they’ve been on one interminable losing streak. No wonder they walk through the halls in despair; no wonder they lose their confidence and retreat, relying on skill sets they’ve been told they are good at, rather than expanding the limits of their art. Who wouldn’t?

I’m not saying that revision—and the endurance needed for multiple revisions—isn’t important. Of course it is. My point is merely that there are psychological components to teaching and learning to write, whether we acknowledge them openly in our classrooms or not. And if we focus mainly on fixing the fleeting problems of each manuscript, we may overlook the more enduring problems of each student. And that’s dangerous and inefficient, because the problems in each student of course create—and recreate—the flaws and limitations in their manuscripts, or sometimes prevent them from producing a text in the first place. We acknowledge that athletes need psychological strength and skills as much as physical ones. Why would writers—those “athletes of perception,” to quote Robert Stone—be any different?

Leahy, Anna. Power and Identity in the Creative Writing Classroom: The Authority Project. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 2005, p. 14.