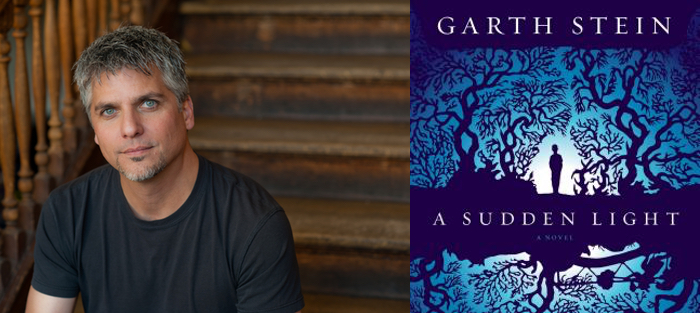

Garth Stein’s latest novel, A Sudden Light (Simon & Schuster, 2014), follows the success of The Art of Racing in the Rain (Harper Collins, 2008) and has its origins in a play he wrote in 2005. A Sudden Light showcases Stein’s atmospheric prose style and tells the story of a man reflecting on a particularly formative summer from his childhood. Set in the Puget Sound—Stein’s own boyhood stomping grounds—the novel contains a 100 year-old timber-money mansion, a plotting ghost, and, at the heart of it, a boy piecing together the puzzle of his family’s obscured history.

I caught up with Stein for a chat between tour stops, and we got into some interesting comparative territory. He likens writing A Sudden Light, his fourth novel, to Haruki Murakami’s marathon training routine. He relates the creative process to playing tennis, and, well, not playing tennis. He offers an anecdote about how his former karate Shihan influenced his daily writing habits.

Stein lives in Seattle with his wife, three sons, and their dog, Comet

Interview:

Brandon Bye: You have a background in filmmaking. How did you transition to writing fiction?

Garth Stein: Yes, I have an MFA in film from Columbia, and I made documentary films for about eight or nine years, which I really enjoyed doing. It’s a lot of fun. But I got very frustrated by the fact that I was constantly raising money. Ninety percent of my energies went into getting the funding to make the film. And that’s when I started writing. I wrote my first novel, Raven Stole the Moon (Simon & Schuster, 1998), out of frustration, and it went quickly to process. I said, well, that’s easier than making documentaries—I should become a writer now. Little did I know it would take me five years to write my next novel.

How Evan Broke His Head.

How Evan Broke His Head.

Yes, that came out in 2005. And I had written a play called Brother Jones that had a production in 2005, too, in Los Angeles. And it went well, but the play needed work. It needed to be workshopped. But I didn’t have the energy to do it because I had this other idea to write a book from the point of view of a dog. And that’s when The Art of Racing in the Rain happened. Of course that’s the book that went ballistic and spent three years on the New York Times bestseller list. So when that was done, I said, well now what do I do? I have to write another book. I refused to be the guy who writes dog books, so I went back to the play I had written and decided to write it as a novel. So that’s how A Sudden Light came to be.

What playwriting craft elements carried over for you?

When I wrote the play I wanted the set to be a character, to interact with the other characters. So in the play the set sighs and moans and groans and all those sorts of things. When I wrote the novel, I really wanted it to take a personality, to be almost a sentient being. In the same way that trees are referred to in the book as sentient being with slower metabolisms. And there’s a lot of dialogue, and there’s a lot of theatrics, if you will.

The trees, yes. I read you climbed some pretty tall trees during your research phase.

I wanted the characters to be climbing these tall trees, so I got a hold of a guy in Portland, Oregon, who climbs trees for a living—his name is Tim Kovar—and I asked him to take me up into trees. Pretty amazing stuff. We climbed a three- hundred-year-old redwood down in the Santa Cruz Mountains. It’s an eye-opening experience. When you’re up in the tree, three hundred feet above the ground, and you can’t see the ground, the branches are so dense and the world up there is so lush, you feel like you’re being held by the tree. It’s a totally different relationship with a tree when you’re up at the very top of it.

What a cool experience. You must have gone through a phase in your writing, before having the backing to commission professional Oregonian tree climbers, in which you mined past experiences for material. One of your big themes seems to be coming to terms with the past, interpreting the past.

I mean, everything is informed by one’s past. My first book was Raven Stole the Moon. I took a lot from my mother’s history. It’s a spiritual thriller using Tlingit Indian mythology that takes place in Alaska in a small fishing village. Tlingit is on her side of the family. With How Evan Broke His Head and Other Secrets, Evan has a very severe form of epilepsy, which is what my sister grew up with, so I have a very informed connection to that. What came from my past with A Sudden Light is the location. I grew up in Shoreline, just north of Seattle, in an area just down the hill from The Highlands, a very exclusive, gated community. It was started around the turn of the twentieth century by the richest of the rich. And still today, there are some amazing mansions up there, mostly owned by Microsoft people. In the old days it was owned by the likes of Bill Boeing and the big timber barons. I grew up down the hill from there and always wondered what it was about. When I was a kid, parents had a whole different attitude about raising kids. Now everything’s got to be scheduled out. Kids are very highly managed. Both my parents worked, and my mother would say here’s a few dollars for lunch, be back by dinner, and don’t get yourself abducted. So we did all sorts of crazy stuff in the woods, and I wanted to capture some of that. That’s most of the reason why I use the lens of adult Trevor telling the story of what happened when he was fourteen-years-old to his family. I wanted it to be about perspective, apropos of the epigraph—Anis Nin: We do not see things the way they are, we see them as we are. When we tell stories we change them and embellish them, tightening up certain things, expanding certain things. Brian Williams is in trouble for that right now.

I mean, everything is informed by one’s past. My first book was Raven Stole the Moon. I took a lot from my mother’s history. It’s a spiritual thriller using Tlingit Indian mythology that takes place in Alaska in a small fishing village. Tlingit is on her side of the family. With How Evan Broke His Head and Other Secrets, Evan has a very severe form of epilepsy, which is what my sister grew up with, so I have a very informed connection to that. What came from my past with A Sudden Light is the location. I grew up in Shoreline, just north of Seattle, in an area just down the hill from The Highlands, a very exclusive, gated community. It was started around the turn of the twentieth century by the richest of the rich. And still today, there are some amazing mansions up there, mostly owned by Microsoft people. In the old days it was owned by the likes of Bill Boeing and the big timber barons. I grew up down the hill from there and always wondered what it was about. When I was a kid, parents had a whole different attitude about raising kids. Now everything’s got to be scheduled out. Kids are very highly managed. Both my parents worked, and my mother would say here’s a few dollars for lunch, be back by dinner, and don’t get yourself abducted. So we did all sorts of crazy stuff in the woods, and I wanted to capture some of that. That’s most of the reason why I use the lens of adult Trevor telling the story of what happened when he was fourteen-years-old to his family. I wanted it to be about perspective, apropos of the epigraph—Anis Nin: We do not see things the way they are, we see them as we are. When we tell stories we change them and embellish them, tightening up certain things, expanding certain things. Brian Williams is in trouble for that right now.

A few too many embellishments.

A few too many bullets flying past his head. But that’s the way it works. As storytellers, it’s in our nature to try to please our audience.

Can we talk about John Irving? Process, really. Can we shift gears?

Ok.

John Irving famously starts his writing process by writing the last line first. What comes first for you?

That’s a chicken and egg question. Every book is different in how it writes. How do I say this? It’s kind of a little bit weird probably, but the writer has to allow the book to write itself. I totally agree with John Irving in the sense that I need to—and I’m big on structure, having a background in theater and film—I need to know the ending. I don’t need to know that last sentence. There’s actually a tradition in theater: as an actor, you never say the last line of a play until opening night. As an author, I would never write the last line of a book because I would be, in some way, breaking the tradition of the theater.

So what’s your process?

The first draft is for me, in the sense that I’m trying to do something. I’m trying to make it work, writing toward a certain ending. Ever subsequent draft is not about me anymore, it’s about the work, and it’s about the character, and it’s about the story. I believe the writer has to set his ego aside after the first draft and say, now I am a servitor to the greater thing that I’ve created. It will tell me what it wants, and I have to be true to it. I can’t force a character to do something because I think it’s cool. You can’t contrive an event to occur that isn’t in the nature of the story, or else the writer breaks the promise of delivering a story that is genuine. And usually that happens because the writer just wants to get the stupid book done. I’m working on a new book right now, and I don’t even know what’s going on. I had 15,000 words and I thought it was practically done. It was one of those times when the story just drops in and I’m just typing. But now it’s starting to get weird and funky on me because I’m discovering things about the characters and world that are surprising to me.

It’s interesting to hear writers talk about listening to the story, to the characters telling them what to do. It’s like an imaginary friend.

It’s interesting to hear writers talk about listening to the story, to the characters telling them what to do. It’s like an imaginary friend.

Well, it is. There is a certain amount of psychosis in the creation process. I think for a work to really ascend, there has to me something magical in the creation of it. It’s the difference between the art and the craft. The craft we can teach. We can get really specific about POV, about voice, tone, word pattern recognition—pretty sophisticated stuff. And great. But then there’s the art. The art is the stuff that only comes from inside the heart and the soul of the creator. That’s the stuff that’s harder to explain. And you have to work a lot harder at that. When I start dreaming about my characters I know I’m in the thick of it. Murakami wrote a book called What I Talk About When I Talk About Running.

I didn’t know he was a runner.

He’s a huge marathon runner. It’s a very interesting book not about writing. He says people say to him, “You must think about your stories while you’re running.” But he doesn’t. He says, “I don’t think about it at all. I think about running.” I’ve toyed with the idea of running a marathon. There’s 150,000 marathon training guides. The first day you run two miles, then you run three miles, then you run six miles on Saturday, then you take a day off. You get a whole half-year regiment to train. And you need to do that to prepare your body for the shock. When Murakami runs a marathon, he doesn’t do that same schedule because his body knows what it takes. It’s the same thing with writing. When you’re writing a novel for the first time, you need to write every day because you need to condition your creative muscles to be prepared for the ordeal of creating a book-length work. When you’ve written five novels, your body knows.

What about that day off?

Sometimes writing is about not writing. The characters are with you all the time, but you need to have a release because sometimes when you get away from your characters they do things. They secretly change something. Or they learn something. And then when you go to write them again they tell you what they’ve learned and how they’ve changed. And so you need to have escapes like running. I play tennis. I love to play tennis. And I’m not thinking about the book when I’m playing tennis. You need to give yourself that breathing space. That’s where the fermentation process really grows. If I have to go on tour and don’t pick up my racquets for two weeks, sometimes that first day back on the court, it’s like I can’t do anything wrong.

Absence makes the art grow stronger.

Yes, I think it does. There’s something about letting it sit, letting it steep. It’s very interesting. The whole creative process I find fascinating. I took karate for a number of years. I was six months away from testing for my black belt, and then we moved to Seattle. When you get to the higher levels, the Shihan comes in to watch the training. In an hour and half training he would always come onto the mat with twenty minutes left in the class. And I asked him why he doesn’t come at the beginning of class when everyone is fresh and excited and has energy. He said, “I tell you why.” He said, “Because in the beginning of class you’re trying to do things. By the end of class you’re so tired, you’re only doing what you know. You can’t think anymore. You’re only going on instinct. That’s how I know where you are.” A lot of people write in the mornings. I don’t. I tend to write in the late afternoon or at night. I use the fatigue. The fatigue factor allows me to not think too much about what I’m trying to write, but rather allow the writing to happen. And when the subconscious intuition comes up, for me that’s the art stuff.