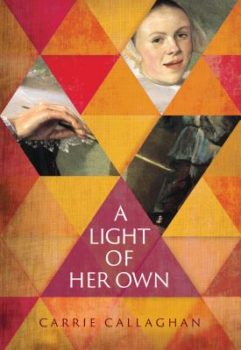

Fans of Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with A Pearl Earring and Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist, hungry for art-themed dramas set in seventeenth-century Holland, look no further than Carrie Callaghan’s debut novel, A Light of Her Own (Amberjack, 2018). Using the scant documentary evidence from Judith Leyster’s real-life history, admirable restraint, and convincing, evocative prose, Callaghan illuminates the prejudice and repression that beset the career of this forgotten heroine from the Dutch Golden Age.

It’s a story that deserves to be told, and one that twenty-first–century readers will appreciate. With a combination of talent, passion, and grit, Leyster struggles to become the first female artist accepted into the illustrious Saint Luke’s Guild of Haarlem, eventually earning her own studio and teaching at least three male pupils. Though her paintings were attributed to her husband and other male artists for centuries, her oeuvre was eventually reattributed to her in the late nineteenth century. Today her lively portraits, genre works, and still-lifes are owned in major collections around the world, including the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; the Louvre, Paris; the National Gallery, London; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

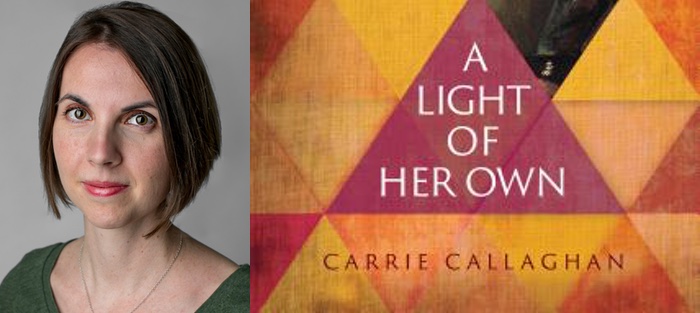

Callaghan’s short fiction has appeared in the Silk Road Review, Floodwall, the MacGuffin, the Northern Virginia Review, and elsewhere. She’s the senior assignments editor for Washington Independent Review of Books. She lives in Silver Spring, Maryland, with her husband and two children.

Callaghan and I conducted our conversation over email.

Interview:

Kate Lemery: What inspired you to become an author? What were the first things you wrote?

Carrie Callaghan: Like so many lovers of words, I started writing as a child. My first public book reading was to my third-grade class, the poor souls. But I didn’t think it was possible to be an author—authors started off famous, somehow. So my first two completed works were a picture book about a bear that ends a war by stealing the enemies’ clothes, and another about a flying pumpkin superhero. (I had enough discernment to know the second one was derivative and not very good. I liked that pacifist bear, though.)

What is your educational background and how did you learn the craft of writing?

I have a master’s degree in international affairs and economics, and an undergrad degree in international studies and Spanish. The only writing class I’ve taken was the Jenny McKean Moore community workshop at George Washington University. I learned a lot about writing with concision and grace from my graduate school professors, particularly Eliot Cohen, who is a tremendous writer. Fourteen years later, I’m still learning how to translate that into fiction.

How do you structure your days when you’re writing, and do you need any specific elements in order to craft prose—tea, chocolate?

How do you structure your days when you’re writing, and do you need any specific elements in order to craft prose—tea, chocolate?

I have a full-time day job and two young children, so my writing time is at best an hour in the evening when they’ve gone to bed. By then I’m usually winding down with a cup of herbal tea. If I’m lucky enough to get a whole day to write, I drink loads of green and black tea. I’m not really a snacker, which feels like a professional failing.

You’re a 2018 Adult Mentor for Pitch Wars. What is your best advice to aspiring authors?

Write because you love it. Sustain yourself with the joy of creation, and treat publishing like the game of chance that it is. If you’re learning about the craft and loving the experience, you’re succeeding. Setting goals for success that are beyond your control (getting an agent, selling a book, becoming a best-seller . . . ) is a recipe for madness. That said, I still succumb to that madness at times. But with the help of Pitch Wars and my other writer friends, I do my best to stay grounded. I wish the same for other writers.

A Light of Her Own, was inspired by a 2009 National Gallery of Art retrospective of Judith Leyster’s art. Would you share some of your impressions of that exhibition? Which painting in particular captured your attention and for what reason? Were you familiar with Leyster’s painting before you saw this exhibition?

I had never heard of Judith before walking into that gallery and seeing her bold face staring back at me. I love art, but I have no educational background in it. To compensate, at least once a year I take a day off to go to the National Gallery of Art and soothe my soul with the artwork there. One of those days just happened to land me in that retrospective, on the occasion of her 400th birthday, and I was stunned. Who was this woman who had succeeded as a painter in the time of Rembrandt? How did she do that? I knew I had to write her story.

Everyday life in seventeenth-century Haarlem is so vivid in A Light of Her Own. How and where did you conduct your research?

Research is one of the joys of writing historical fiction. By setting myself the challenge of recreating a past world, as much as I can at least, I have tasked myself to learn about another facet of humanity. I read all the books I could find (in English) about seventeenth-century Holland—from Tulipomania by Mike Dash to Craft Guilds in the Early Modern Low Countries, and plenty in between. I also had the delight of consulting the artworks themselves for details about life then. And finally, the true experts (Frima Fox Hofrichter at the Pratt Institute and Melanie Gifford at the National Gallery of Art) helped steer me in the right direction when I erred.

What did you do to set the tone to be able to write about Holland during this time period? Did you listen to certain music? Read certain books? Watch certain films?

When I’m writing a book, I’m wary of absorbing other people’s creativity on that same topic. Part of that is the schoolgirl fear of being accused of plagiarism, and part of it is a lack of confidence about my own work. Since so much of what’s available today about seventeenth-century Holland was created recently, I mostly stayed away from it. That said, I did read both The Girl with the Pearl Earring and The Miniaturist, once I had finished drafting. (And thoroughly enjoyed them both, of course!)

Do you paint? If not, how did you learn about the processes and tools?

I wish I did! My mother and grandmother are both excellent painters. I used to draw, but have lost the practice in my adult life. I learned about Judith’s painting from the excellent scholars who have studied her and her paintings so closely over the years. Ernst van de Wetering’s Rembrandt: The Painter at Work was both a bounty of information and a joy to read.

As you mention in your Historical Note at the back of your book, few facts survive about Judith Leyster’s life. How did you decide upon her personality?

We’re lucky to have Judith’s face, in that compelling self-portrait that I was thrilled to be able to put on the cover of the novel. There’s so much personality in her expression and her bearing. From there, I added what else we know—her self-confidence in bringing a lawsuit against the family of a former apprentice; her habit of writing notes to herself; her family’s lackluster history. Between those lines I sketched a person. I hope I did her justice.

One of my favorite elements about your novel is the rich and realistic friendship between Judith and fellow artist Maria de Grebber. What was your inspiration for that relationship?

I’m deeply moved by questions of friendship, loyalty, and sacrifice. I think friendships are among the most beautiful relationships we have. They’re not prescribed by genetics, they’re not evolutionarily convenient for child rearing. They’re both less constrained and more challenging for being free of those social bounds. I knew I wanted to write about the question of sacrifice, and a friendship seemed the most interesting way to do so.

If you were able to meet Judith Leyster, what questions would you have for her?

Was it a good life?

Is there one takeaway you’d like to leave readers of A Light of Her Own with?

I’d love to think I leave readers inspired by Judith’s history, and maybe also thinking about the role of women’s ambition and what sort of sacrifices ambitious people need to make. But the best gift would be if someone were to reach out to a beloved friend as a result of reading.

What are some of your favorite books? And what are some of your favorite books to read to your children?

You know you can’t ask a writer that question, Kate! How can we pick? If you force me, I’ll say I adore Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety for showing me how rich historical fiction could be; Song Yet Sung by James McBride for being emotionally profound and wise; Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro for leaving me in tears; and The Women in the Castle by Jessica Shattuck for being the brilliant, complex book about idealism and female friendships that I wish I could write.

As for reading to my kids, well, that’s pretty much why I had children, for that feeling of a small child in my lap, curled up with a book. My daughter and I just finished reading When the Sea Turned to Silver by Grace Lin, and we both adored it.

What are you working on now?

Another historical fiction about a brave woman who got lost in history’s shuffle—this time, an early twentieth-century female journalist who was complex, sensitive, brash, and lonely. I adore her, and hope other people will get the chance to learn her story too someday!

That sounds wonderful. I can’t wait to read it.