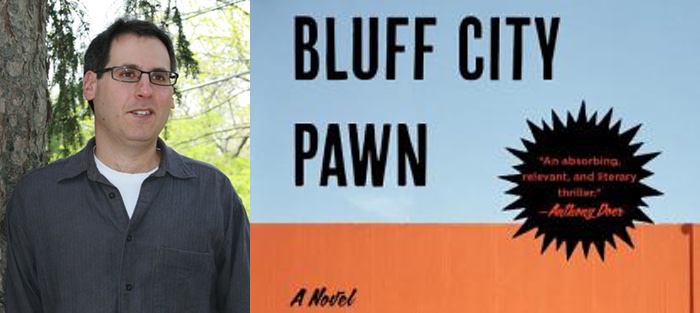

In the fall of 2013, I asked Stephen Schottenfeld if he would visit the Writer’ Craft class I was teaching at SUNY Brockport, just west of Rochester, NY. I had heard Stephen read from his then novel-in-progress, Bluff City Pawn, and thought my students would enjoy meeting him. Not only did he agree to venture out on a cold late-autumn evening, he sent me the first two chapters of his novel so my students could get the flavor of his work ahead of time. My students—a mix of literature and creative writing majors, undergrads and grad students alike—loved his work and (I was wee bit jealous) they loved him! His generosity and openness about his work was infectious.

Given this response, I invited Stephen to give a reading the next year at the Brockport Writers Forum, the visiting writer’s series that I co-direct. Stephen had come to town a few years earlier to teach in the English Department at the University of Rochester, and I wanted to help celebrate his new book, and to introduce a new writer to the western wing of Rochester’s literary community. Also, given that the country was still suffering the long hangover from the “housing crisis,” I thought the reading would have a certain relevance, and resonance. I wanted folks to meet “the Marrs Brothers,” Joe, Huddy, and Harlan, characters that I had come to think of as the Three Wise Kings of Reagan’s Trickle-Down Shell Game, or the Three Horsemen of the Economic Apocalypse, or, maybe, the Three Stooges of the AIG/Goldman Sachs Mortgage Crisis. More essentially, these Memphis boys are classic American types, well-intentioned shady-dealers beautifully caught between Emersonian self-reliance and Willy Loman’s self-delusion. As part of Stephen’s reading at the Writers Forum, we sat down for an interview in the TV studio on the Brockport campus. An edited transcript follows.

Interview:

Ralph Black: You know, I was lucky to get an early copy of the book. I’ve taught it, and I’ve read it a couple of times. I’ve read that opening section a number of times, and I’ve heard you read it. As you were reading it, I just thought that Huddy, from the very first page, is swimming around in this world. He’s been swimming it for a good while before we see him in the first page of the novel. That Memphis is kind of ticking along and doing its thing. That the world of the pawnshop, the wheeling and the dealing, and his awareness of where everything is and how the whole machine works. Which leads me to kind of an amorphous question about your sense of the novel, and where it started for you? He’s such a compelling character to me. Did it start with him in that world? Was it the pawnshop you saw out your window in Memphis?

Stephen Schottenfeld: Yes, I definitely started with him. I think I was so interested in what he was doing as a pawnbroker—what was coming through his door—that it took me a little while to realize that he couldn’t, in and of himself, be the book. The storyline would be too narrow. So I started thinking about ways to broaden it—thinking about his family, his brothers. But I was interested in what you were saying because—it’s funny, I’m trying to think about what the beginning is, and it’s quieter in the sense that nobody is there yet. He’s not talking to anybody. But it does seem like what you’re saying is that even though the workday hasn’t started yet—the store hasn’t opened—he’s still very much caught up in the middle of things, thinking about what happened overnight. And things are already a little askew with the daylight savings, you know, things aren’t neatly aligned. There’s already that problem in the air for him.

And an awareness that it’s a really thin line. He seems to pride himself on being conservative about how he runs the business. He’s really careful, and he’s really interested in control. Yet, he’s aware of the fact that it just takes nothing for that control to vanish, and for things to spin out of control.

Right. I looked at a lot of different pawnshops and a lot of different pawnbrokers. Mostly, I saw pawnshops that were very careful, very pragmatic, and skillful. But I also saw one pawnbroker who I thought it just seemed inevitable that something bad would happen there. The store was in a very bad area, but he just seemed really hyped-up. You would hear about pawnbrokers that were making bad decisions, and had gotten intro trouble, but the ones that I became closest to, I admired how they worked. How they stayed in control of situations that, to me, seemed very precarious. I wanted to give my character that attention to detail. And also, someone who is very aware of trouble, but didn’t necessarily magnify it if it was something that could destroy his business or destroy his day. I still wanted to figure out how trouble could find him. So I guess that was maybe the impetus for how he operated—really careful with putting stuff out on the showcase, doing everything in a very intelligent, thoughtful way, and thinking about how things could slip from there. I wanted to set the bar high for him. Also, in some way maybe in deference to some of the things I was seeing.

Right. I looked at a lot of different pawnshops and a lot of different pawnbrokers. Mostly, I saw pawnshops that were very careful, very pragmatic, and skillful. But I also saw one pawnbroker who I thought it just seemed inevitable that something bad would happen there. The store was in a very bad area, but he just seemed really hyped-up. You would hear about pawnbrokers that were making bad decisions, and had gotten intro trouble, but the ones that I became closest to, I admired how they worked. How they stayed in control of situations that, to me, seemed very precarious. I wanted to give my character that attention to detail. And also, someone who is very aware of trouble, but didn’t necessarily magnify it if it was something that could destroy his business or destroy his day. I still wanted to figure out how trouble could find him. So I guess that was maybe the impetus for how he operated—really careful with putting stuff out on the showcase, doing everything in a very intelligent, thoughtful way, and thinking about how things could slip from there. I wanted to set the bar high for him. Also, in some way maybe in deference to some of the things I was seeing.

It’s not accidental, I’m sure, that the story takes place at a time in our recent history where the economic bubble is bursting and things are really falling apart. To me, one of the things I admire about the novel is the interweaving of the personal and the political. You get this very intimate story of relationship between and amongst these three brothers, and yet this story is localized. It’s these three guys. It’s not just in Memphis, but in a small part of Memphis. The implications are much larger for a number of places where Huddy and Joe are taking about money, power, and what they allow. Joe, at some point, says, “Money buys me.” He doesn’t mean stuff, rather, power and access. It should be easier.

It’s interesting, because I would’ve always been writing about money, whatever the timeframe. The main setting is a pawnshop. I think that when I started researching the book, right at the start, the recession hadn’t hit yet. So what I felt like I was doing was localized. I felt like I was writing it from the inside out. What are these characters doing, and how can I explore the ramifications of that in the wider world of the city. When the recession hit, I did feel like there were these external factors that began to push into the book. What I mean by that is Joe, at the beginning of my conception of the book, he was the brother that had gotten out. He was the success story. But he was sort of a non-story. There wasn’t anything about him, to me—unless Huddy were to inflict something upon Joe, I didn’t necessarily see how Joe was going to be made vulnerable in the book. I had decided, again, that like Huddy, he was pretty skillful at what he was doing, so he wasn’t necessarily making a lot of mistakes, or wasn’t necessarily being reckless. Then, as ’08 and ’09 unfolded, and you saw what was happening to builders in Germantown—millionaire builders that were beginning to lose their business and maybe even their homes—that affected the trajectory of the story, and also affected what Joe needed to do to keep himself afloat. Huddy was affected by the attention that gold buying suddenly got. You started seeing articles, in The New York Times–everyone was aware of the price of gold suddenly. Everybody was getting into it. That shaped the book. I’m not quite sure what the recession did for Harlan, who was already a bottom-feeder. It couldn’t have helped him find a job. He’s a bit more of a self-sabotager than the other figures. But I don’t think it was a positive force for him. I think the recession shaped the narrative for all three brothers.

Can you talk about your education? How does one become a novelist? Were there teachers along the way? Were there books that you read? Readers that fed you? And you thought, “I just need to do this thing.”

I don’t remember a particular book or a particular moment that I thought, “I’m committing to this.” I felt like I was kind of wading deeper and deeper into that reality. I toyed around with writing in college. I wasn’t a huge reader growing up, which was a detriment to my development. What I mean by that is that it slowed me down. If I had been more of a serious reader when I was thirteen and fourteen, it would’ve accelerated my awareness of all the things I didn’t know that I needed to read subsequently to that. For whatever reason, college seemed to be the start. I started to love stories, and I started to seek out writers that were part of some of the reading lists we were doing—some of the anthologies. In some ways, it was when I left college that I started to compile different reading lists of my own, looked at interviews, saw what writers that I admired had read, and started to track those down. How I become a novelist was simply the outgrowth of the length of the stories that preceded them—moving from shorter stories to longer stories to the novella Summer Avenue, and finally to this novel.

I had a teacher in graduate school who made a very small comment. She was asking me what I’m going to do. She said, “You will keep at it, won’t you?” It was this throwaway line that meant everything. Maybe it wasn’t a throwaway line. It seemed like she was seeing through me for a second in a very positive way.

I’m curious as to who, when you started to get more of a sense of direction particularly as reader, who the writers were. It sounds like you were tracing a constellation. Not just reading one writer, but what were they reading? What were their influences?

I’m curious as to who, when you started to get more of a sense of direction particularly as reader, who the writers were. It sounds like you were tracing a constellation. Not just reading one writer, but what were they reading? What were their influences?

Well, in no particular order: reading Philip Roth was big, Saul Bellow was big, Malamud, Beckett was huge. Not necessarily Godot, but Endgame, Molloy. I just didn’t know that kind of novel existed. Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman.” When I read it, I just felt like I was seeing something entirely new, and feeling shocked that it had been there for 150 years. Flannery O’Connor, Russell Banks, and Denis Johnson were significant. Faulkner was a kind of awesome experience. I remember reading Absalom, Absalom! and thinking, “How could I be a writer if this is what writing really is?” So, it’s one of the books that is one of my most favorite books, but I can’t really say it galvanized me. In some ways, it frightened me. It just seemed so big. Other writers—there are so many!

I’m curious about your list. The first half of the list strikes me as really urban. There’s a lot of New York City writers. Just really urban, whether it be Moscow… Do you think of yourself as an urban writer at all?

I think of myself as some kind of combination. I’m very interested in different lines of influence. I teach this Beckett class that explores his absurdist, blasted influence on Coetzee, Pinter, Auster, Lydia Davis, Donald Barthelme, and George Saunders. There are pieces of all those writers that I feel like I have absorbed. Maybe there are minor gestures that I make in my writing that pull me in their directions. But then, there are other writers, from other aesthetics—like realism. I don’t think I have a particular line. When I was living in Memphis, I was very interested in the city, and what was going on there. I brought an interest in writing about work lives before that.

Bluff City Pawn seems to be about Memphis in so many ways. It’s the specificity of locations—Lamar, Summer, and Germantown. It seems there is a map-like quality. What I’m wondering is: do you think this novel needs to take place in Memphis? Could you transplant it to a different city?

Well, I think it needs to take place in Memphis, but I think there are things about it that speak to a host of cities. A part of what made me want to write it was coming down to Memphis from the Midwest, and just being struck by the large number of pawnshops there. Obviously, every city has its divides of class and race. Then again, as an outsider, coming to Memphis and thinking about Martin Luther King, and his assassination. I just remember during those first few months thinking about seeing someone of a certain age: “Where were you in 1968?” In a general sense, what I’m saying about the city could apply to any number of places dealing with white flight and concentrated poverty. And then, in some ways, it’s very much about Memphis. These characters are very much from that particular reality. I was trying to bring a certain anthropological eye and a certain attention to the speech patterns of the characters.

I’d like to ask you about that: the anthropological eye and the anthropological ear. The voice and the voices of the novel are so powerful. One of the things that I wondered about was your decision to try—well, I don’t know if this was your decision—to try and evoke some American idioms, Southern idioms of speech. There’s a lot of clipped syntax, conjunction, right? Both in Bluff City Pawn and in Summer Avenue as well. Can you talk about that?

I think that Summer Avenue was even more of a challenge in that it was a first-person narrator. I was confronting the voice right from the get-go. In this, I certainly feel like it’s a close narrative in the sense of the limited narrative as my narrator is so often channeling Huddy. I do feel a little more distance. Voice. There’s dialogue and then there’s, as I said, the narrator behind it. I wanted it to feel like a book that was set in Memphis. But I also didn’t want to try and appropriate, lazily, some kind of clichés of diction—dadgum this. I think that was something I was anxious about. I want this to be a Southern novel. And living in the south for a number of years, well, what does that mean? I was certainly listening a lot when I was there. I was just trying to be as truthful as I could to these characters, and trying to hear them in a way that felt right. Not over-emphasized, but not under-emphasized. You know what I mean? If you’re afraid to write this thing as a Southern novel, you’re going to fail that way. But there’s also a way that if you don’t stare at it long enough, you’ll be a tourist of the language. You won’t really get inside of it. You’ll just grab these shopworn moments.

I don’t know if this is a fair question, but what the hell: Are you happy with how it worked? Do you look back now and think, “Yes, I nailed it.”

When the book first arrived, I couldn’t look at it at all. It just felt too painful and inadequate—without really even reading it, just opening it. It felt like this little, flat thing.

I hear remorse.

Yes, so I felt failure there. I don’t feel that anymore. It’s not as despairing as that. Maybe I’m afraid to go into the book to confirm my suspicions of it. But when I read it, it read OK, you know? I think I’ve come to a certain peace about the book in that I spent so much time researching things. I feel like some of the reviews have talked about where the book takes you—not to Graceland, but to some other places that are not so obvious. But I don’t know if I ever feel that I nailed it. I guess I feel that I could’ve failed worse.

Speaking of Beckett, fail better.

I think so. I think I was able to develop Huddy to find out what his dreams were. And to say something about these characters. That meant something.

I have another question here relating to voice, and also to narration. One of the things that struck me about the novel are the places where—I guess it’s really everywhere—in the limited third person, you’re able to describe an event. You can create a scene where Huddy, his psychology is interwoven between everything. Sometimes, there’s a lot of dialogue in the novel. But sometimes, you can have six lines of dialogue that take three pages to happen because there’s so much exposition. Right? I wondered about that work for you as a novelist, to sort of propel action through dialogue. Then, also, let Huddy’s consciousness play its central role.

That may be a place—you’re asking me about my development as a writer—that I’ve grown the most as a writer. I was always interested in dialogue. Partially, because I worked in film a bit and screenwriting after college. I think that when I was first getting serious about writing I could feel that my dialogue was getting better. But those stories were very spare, and I don’t think that there were these spaces you’re talking about, the depth of the character maybe. I think that is something that grew through the writing of the book: through my writing, the spaces between the dialogue. For a while, I was probably thinking a lot about silences inside the dialogue. You know, Beckett, Pinter, all the gaps. Maybe in this book I also was able to start to develop the interiority, a spoken quality that’s happening outside of the speech. The way that Huddy’s mind is sort of working. If you look at the scene where Huddy was doing the sale, trying to buy all the guns, it’s a big kind of poker game in a sense. There are these gestures that are going on in this transaction. But there is so much that is happening with Huddy internally as he takes in the ramifications of what he’s seeing, and also trying to stifle what he’s showing back. What he’s seeing is something monumental. In that sense, it worked kind of well, that he couldn’t say everything, even a fraction, or maybe even the most important thing that he was feeling, which was, “O my god, my life could change.” He had to look like an ordinary thing, but he couldn’t lie about that too. He had to make it look extraordinary, because it was. But he also had to make it look like he dealt in the extraordinary.

The same thing happens in that scene, and also at the end of the novel when the ATF agents show up at the shop to take the guns. And again, there are very few lines of exchange, but so much of Huddy’s building nervousness and anxiety where he’s basically watching everything crumble.

You know, I hadn’t thought about that, the relationship between those two scenes. They’re sort of the inverse.

I think so.

And in a way, so much is churning underneath that. I’ve wanted to read the ATF scene, and I’ve never read it because I feel like it gives away so much of the book at a reading. So if I were to read it, I’d give it away. It’s pretty far along in the book. But you’re right. It’s the mirror image, and they have the papers this time. I guess, every moment you write is placed against the other moments. If.. as you said, you have dialogue and pages of introspection, that moment comes out in stark relief against perhaps another conversation that functions in a much faster dialogue fashion. Part of it is just how do I create tension. A lot of the tension is just what’s going on in Huddy’s mind. What can he say? What can’t he say? He’s in a lot of trouble in that scene. He’s really trying to give the perfect answer.

In both of those scenes, both at the Yewells’ house and at the shop with the ATF agent, I think that your mention of poker is exactly right. He can’t talk about either how much or how little is in his hand, but we get to see behind the curtain. Both the sort of hopes and dreams of what this guy has got. I could walk out here with a truckload of valuable guns and get off Lamar. It is that kind of wonderful moment of the American dream—that great possibility.

I chose the Dreiser epigraph, from Sister Carrie. When you look at the trajectories of the characters in his books, whatever people have to say about the language. You look at the transformations. I can’t even remember the name of the man in Sister Carrie, but the downfall of that man is just extraordinary. I do suppose I was trying to write something in the American grain that way. I’m not saying I achieved it. Huddy is a dreamer. He is an American. I wouldn’t call it a rags-to-riches thing. It’s not like he’s looking to become a millionaire. But he sees an opportunity to change his life forever.

I chose the Dreiser epigraph, from Sister Carrie. When you look at the trajectories of the characters in his books, whatever people have to say about the language. You look at the transformations. I can’t even remember the name of the man in Sister Carrie, but the downfall of that man is just extraordinary. I do suppose I was trying to write something in the American grain that way. I’m not saying I achieved it. Huddy is a dreamer. He is an American. I wouldn’t call it a rags-to-riches thing. It’s not like he’s looking to become a millionaire. But he sees an opportunity to change his life forever.

Something I love about the novel is that it’s not “I’m gonna hit it big.” It’s not about the lottery. I mean, it’s fifty-grand that they’re hoping to clear?

Well, he’s hoping to clear, let’s see. I guess he thinks he could sell it for about three-fifty. So he’s looking to make a profit of about two-hundred and fifty thousand basically.

That’d get him a few rungs up the ladder.

Yes. Or maybe even more. Maybe a profit of three-fifty. He’s looking to make a bit of money here.

I’m going to ask you a related question about Heritage Cove. There’s a wonderful passage at the beginning of a chapter. It’s on page 222. Joe and Huddy, or maybe Joe isn’t there. This is when Huddy pulls into Heritage Cove.

Joe is there. He’s in one of the houses, and Huddy is first driving in.

That’s right, yes. So, I’m thinking about it in a couple of different ways. It seems like a kind of a synecdoche, and the whole state of the American economic dream. So that’s one question. The other question is that it seems– thinking about how you worked in film–this just seems like a beautiful panning shot with great detail of these houses that seem like they’re ready to be moved into, but a couple of lots over there is just the weeds.

I was aware, as I started thinking of the book as a whole, of how these settings correspond to one another: the claustrophobia of one interior space, the roominess of another interior or exterior space–the movements of the pawnshop to Joe’s backyard, the movement of the pawnshop to Yewells’ estate, the movement of the pawnshop to Heritage Cove. Right before we see Heritage Cove, the ATF agent tells Huddy, “We’re freezing your inventory. None of these guns move.’” I wanted to contrast that confinement with the vastness of Heritage Cove: “Heritage Cove has a brick wall that steps with the gradations of the land.” Huddy’s drive through the development is meant to signal different stages of economic decline: success, stagnation, collapse. A project that started with such promise that’s now come to a grinding halt.

To me, it also seems that this is a place where the pieces of reality come together for Huddy. He’s a smart guy. He can interpret this landscape pretty clearly.

I think that this was a moment where I had to figure out, what’s the book? The guns will be lost soon. How is that not the end of the book? If what’s going on, what Huddy’s going to get in his shop, is the loss of the guns, how is that not the end of the book? I had to really consider how much the brothers were a part of the story–how much Huddy’s relationship to Joe, his relationship to Harlan. The pawn shop is central, and is there at the end. This is very much a story about if Huddy will succeed. But there’s also this other story going on, which is what’s going to happen to the brothers?

I have a question about that. There was a bit of an argument in my class about the end of the novel—whether or not people felt as though Huddy had actually learned anything. He’s going to these auctions, and he’s out of the gun biz, but he’s still pawning. Some students of class felt that he’s taken with Del who said, “There’s another way to play this game.” Some students said, “Yes, he’s really learned. He’s stepping it up a notch. He’s playing it differently.” And some students said, “Well, he’s playing it differently, but basically, he’s trying to buy low and sell high to beat the system. He hasn’t learned a damn thing.”

I think you’re raising a good point about what the values are of what he does, and what the profession means to people. I see, in him, a survivor. But you’re right to question “to what end and to what ethic?” As you said, he’s still getting something that, at times, is coming at him through a kind of sad narrative. There’s something about him that’s remarkable to me, that he’s continuing to try and do this. I think that what has happened with him is he’s come to a new potential with Joe, that they’re bonded by loss. He’s always respected Joe a little bit. It’s not a story of redemption, as your students were saying. It’s funny, it could’ve been sadder even, and the way I’m defining it as not being sadder is that Huddy keeps going. They’re raising a good point. He keeps going, but doing what?

Doing what he knows how to do.

Right. Doing what he knows how to do. At some level, he’s kind of an animal that way. To me, maybe my thinking is warped, but I felt it would’ve been sadder if he wasn’t able to do that thing in any form. But I also think I’m saying something about: isn’t it sad that he’s still doing it?

I loved the ambiguity. I don’t think it’s necessarily your job, or any novelist’s job to tie up those loose ends neatly.

I don’t think Huddy ever says anything at the end like, “I know what I do is this.”

He’s not going to law school anytime soon, right?

No. No, he’s not. Maybe each brother is good at making judgments about what the other brother does. Joe, in a sense says, “If I did what you did, it would tear me up.” I don’t know if that’s a line that Huddy will feel about himself. Maybe that’s what your students are asking—is that a line that Huddy ever internalizes? But of course, he’s saying it in a moment of time in which Huddy can talk right back to him about what Joe is doing–what Joe is about to do is actually quite heinous.

Stephen, we have to leave it there.

Ok!

Thanks for coming in. It was a pleasure.