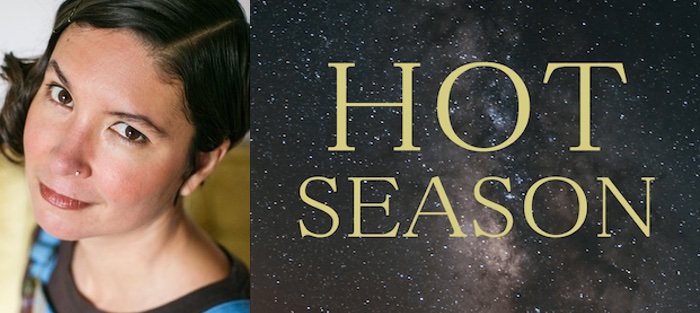

The main conflict in Susan DeFreitas’s debut novel, Hot Season (Harvard Square Editions), is quite simple: three friends at progressive Deep Canyon College (a mildly fictionalized version of Prescott College in Arizona, DeFreitas’s alma mater) confront the threat of development on the beautiful and ecologically fragile Greene River. This river, along with the splendor of the surrounding Southwestern landscape, holds a precious place in the hearts and minds of the Deep Canyon community of students and activists. How far will each character go to save this river is the ultimate question in this elegant, beguiling novel.

Susan DeFreitas is a Michigan native who has lived in Portland, Oregon, for past seven years, but the American Southwest, its people and its flora and fauna, remains her ultimate muse. I sat down with Susan over tacos at a bar in Northeast Portland to discuss activism, fiction, and where the two collide.

Interview:

Mo Daviau: Hot Season takes its place in the relatively new canon of “ecolit.” What titles from that sub-subgenre would you say influenced you the most?

Susan DeFreitas: I would say first of all while “ecolit” is a relatively new term, it is not a new subject for fiction. Many of my favorite books and authors who might fit under that genre—when their books came out they were not labeled “environmental fiction” or “political fiction” but simply fiction: Writers like Ed Abbey and John Nichols, the literary outlaws of the Southwest, and also Barbara Kingsolver. Much was made of her most recent book, Flight Behavior, being an environmental novel, but if you look back as early as Animal Dreams, she was writing about the environment, about human rights, and you find those threads in all of her books. I suppose the human story in her novels is so strong that those human relationships are considered to be foregrounded over societal concerns, but those kind of books remain my favorite ecofiction—like those of Lydia Millet. You can see her environmental concerns, particularly in regard to the extinction of species, throughout all of her books—How the Dead Dream is a notable one—and her most recent book, Sweet Lamb of Heaven, is an astounding novel in light of the recent election. It’s ostensibly a book about a demon who rises to power in the US political system at a time when language has flattened out and become meaningless—but it is a book about the environment as well.

As we are both members of the same writing group in Portland, I’ve had the pleasure of reading a lot of your writing, and your work is profoundly influenced by the American Southwest. What is it, for you, that makes the Southwest, specifically Arizona, so inspirational?

I recently had some perspective on this very question, when I returned to Arizona for my book tour in November, because maybe enough time has passed here in the Pacific Northwest (7 years!) for the Southwest to hit me almost the way it did when I was eighteen years old. Coming out west from the Midwest, the quality of the light—it’s very hard to describe. Saturated doesn’t quite do it justice. Photographs don’t do it justice. The way the sky is in Arizona—they call it Big Sky Country in Montana but that is an appropriate term for most of the American West.

I recently had some perspective on this very question, when I returned to Arizona for my book tour in November, because maybe enough time has passed here in the Pacific Northwest (7 years!) for the Southwest to hit me almost the way it did when I was eighteen years old. Coming out west from the Midwest, the quality of the light—it’s very hard to describe. Saturated doesn’t quite do it justice. Photographs don’t do it justice. The way the sky is in Arizona—they call it Big Sky Country in Montana but that is an appropriate term for most of the American West.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Lydia Millet in her home in Saguaro National Park outside of Tucson. She lives in a place surrounded by giant cacti. Everything there is so alive with birds and lizards—there are places in Arizona that make the woods of the Pacific Northwest seem quite still. The unusual diversity of life in the desert is something I find really compelling. I found it compelling when I first arrived in Arizona and I still do.

Living in the Northwest, I think what I’ve realized is that outside of the Southwest people don’t seem to understand how diverse the landscapes are in those states, and they don’t understand how diverse the people are, either. The conception is that it’s a dry and barren land full of hardcore right wingers, but there are all sorts of people and all sorts of landscapes in the state of Arizona and across the American Southwest. I loved it enough to stay there for 14 years. I still really love it. Hot Season and the two books that will follow it as sequels are essentially what I did with my nostalgia for a place that I still really love.

If a novel needs its characters to want something for the plot to advance, then the concept of activism adds another layer to this want—not only wanting for one’s self but for the betterment of earth and society. How did you perhaps portray the cause of saving the Greene River as its own character?

That’s an interesting question. I think the answer is that the struggle to save the Greene River is a collective desire, as all struggles in the world of activism are. But as in every movement, each of the individuals involved want the cause to succeed for their own reasons. Those reasons are always very personal. You can put a generic label on it, such as “these people want to save the world, they’re all environmentalists,” but all of us have particular events that have shaped us, that have anchored our empathy. Each of us has had events that, as George Saunders calls it, have “politicized us.” What are those events that have opened our hearts and minds to the necessary struggles of the world? For each of the characters in Hot Season, it’s different—for Rell it’s a very particular love for this very particular river: this is the place where she fell in love, where she did her college wilderness orientation. The Greene River is where she fell in love, both with the Southwest, the way I did as a student at Prescott College, and with the guy who broke her heart. The relationship with the guy may be over, but her relationship with this part of the world will endure.

For Katie, who is, for lack of a better word, the antagonist of the novel, it’s much more theoretical. Her activism is about her desire to embody an ideal of a radical activist—as modeled by another of the book’s characters, Dyson Lathe—who poses a sharp contrast to pseudo-liberalism of her mother, a politician. While Katie’s mother plays to environmental sentiments and liberal talking points, she’s really much more a middle-of-the-road political pragmatist.

Whereas, for a character like Michelle—Dyson’s young punk girlfriend, and a dedicated activist in her own right—it’s rooted in the childhood trauma of seeing the woods that she loved being destroyed, witnessing that destruction, as described in the chapter titled “The Underground Waterfall.” Michelle watched a private, beautiful place of sanctuary for her, this place where the river flows underground into a hidden cavern—a place that she only knew about—get bulldozed for a subdivision, which was then called Fox Run. (She calls it Fox Ran.) So, all of these characters are involved in the same struggle, all ostensibly want the same thing, but for different reasons, which are really personal.

The cause of saving the Greene River also affects the three female friends at the forefront of the novel. How does activism affect these women’s relationships?

The main conflict at the heart of the book is one that you will find in many activist communities—perhaps part of what we’d call callout culture—when those newer to the cause who have a lot of fire, a lot of unrelenting, uncompromising black-and-white points of view, take issue with what they see as the backsliding of the older generation, of those who have been involved longer than they have. They hold those people responsible for overall failure of the cause. Whereas in reality, the longer you’re involved in any of these types of struggles—environmental justice, social justice, any hard, huge, overwhelming difficult problem to solve—the more you realize that the answers are not that simple, and that an unrelenting, uncompromising stance can be as harmful to the cause as anything.

But that is also the eternal conversation between generations. Even though Rell is only three or four years older than Katie, I feel like the years we spend in college are so hugely transformative that it might as well be a span of ten years between the ages of 18 and 22. Especially at a school like Prescott College, which of course Deep Canyon College is modeled on, there’s this really vital, really beautiful model of education wherein your mentors and instructors, instead of telling you how stupid and simplistic your ideas for changing the world are when you’re all of eighteen, say, “hey, let’s do it—let’s try to put that into practice.” That’s experiential education. So you get to see for yourself really how complex the big issues are, how difficult it is to change the world for the better.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on revising the next novel in the Greene River trilogy. These books were originally one manuscript, but at the behest of my publisher, I revised the first third of the original manuscript to be a stand-alone title, and I’m going to do that with the next sections as well. The next book is called World’s Smallest Parade, and while it doesn’t feature all the same characters—there’s only one character from Hot Season who carries through—all of the books concern the struggle to save the Greene River, all of are set in the same neighborhood of the same Arizona town, and each one of novels, a person of great consequence to their community dies. The book also concerns the way that Jews in the US played a vital role in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, so I’m excited to dig deeper in my research on this.