When Dancing Girl Press released Pushcart and Lambda Literary Award nominee Carley Moore’s first poetry chapbook, Portal Poem (2017), her bio described her as a “feminist dreamer, kale lover, boot wearer, reluctant multi-tasker, writer, ally, and mom.”

“I try to be an intersectional feminist,” she told me when we met for the following interview. “I’m white and cis and have a lot of privilege; more recently I’ve also come out as queer, but issues of queerness, class, race, and gender have always been central to my work.”

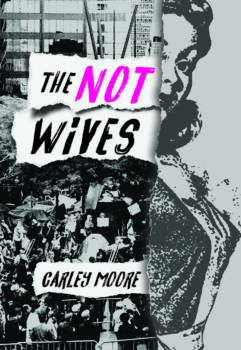

Moore’s first adult novel, The Not Wives, recently published by Feminist Press, is a complex, many-tiered story. The book includes a range of relatable characters, all of them grappling with what it means to live an ethical, productive life. Among the themes addressed are child-rearing, divorce, polyamory, pregnancy, suicide, writing, friendship, sexual exploration, teaching, alcoholism, drug abuse, homelessness, and trying to make ends meet as a working-class intellectual. All of this is set against a backdrop of Occupy Wall Street (OWS), the dynamic, leaderless encampment that brought thousands of diverse protesters to New York City’s Zuccotti Square for two months in 2011.

In addition to Portal Poem and The Not Wives, Moore is also the author of an essay collection, 16 Pills (Tinderbox Editions, 2018), and a young adult novel, The Stalker Chronicles (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012).

Interview:

Eleanor J. Bader: Let’s start with feminism. When did you become a feminist?

Carley Moore: I grew up in western New York and my mother was a second-wave feminist. She started the local NOW chapter with her best friend and worked as the director of the town’s Boys and Girls Club. She taught me a lot about feminism. Later, I went to the State University of New York in Binghamton, and was there from 1990 to 1994. I took a lot of courses in Women’s Studies, even though my major was Creative Writing and Comparative Literature, and had great writing mentors including Milton Kessler, Ruth Stone, and Liz Rosenberg.

But you didn’t major in women’s or feminist studies.

No, but I took courses when I could and have read and taught feminist texts throughout my education. When I first came to New York University for graduate school in 1994—I attended school straight through, from the time I started kindergarten until age thirty-three, when I finished my doctorate—I studied poetry with Sharon Olds and Galway Kinnell. Poetry was my first genre, but once I started to pursue my PhD in English Literature, I was unhappy with what felt like an old boys’ club and switched my major to English Education. I’d started teaching in 1996, as a teaching assistant, and loved it. In the more than twenty years I’ve taught, it has never been boring. I learn so much from my students and they’ve helped me become more radical.

How so?

I’d always taught radical texts, but my goal is to flip the Canon and teach texts mostly by marginalized writers, and my students have responded well to these texts. NYU is a fairly privileged place, but I also have many first-generation college students in my classes and they push me to think more deeply about class and money on campus, which is always an issue.

Occupy Wall Street certainly highlighted class with the slogan, “We are the 99 percent.” I love that OWS plays such a prominent role in The Not Wives. Did you spend a lot of time there?

I probably went to Zuccotti Square five or six times when OWS was going on, usually during daytime hours, and was really impressed by how many people they managed to feed and how accepting they were of everyone who found their way there.

I was not able to stay overnight at the encampment, though; I have a disability, and at that time my daughter was a toddler. But I spent as much time at Occupy as I could. I loved the massive order of it, and I loved that the Occupiers changed the conversation in so many ways. In The Not Wives I wanted readers to see that the discussions and debates that went on in the Square have provoked conversations in America, and around the world more generally, about capitalism, about the nature of debt, and even about socialism.

I know that a lot of people look at OWS as a failure, but I don’t see it that way. I think it led to other movements, other organizing efforts, like Occupy Sandy, the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, and perhaps even some of the rallies that Black Lives Matter organized. OWS had many leaders who brought new tactics to organizing, but the act of just taking over a space became legit again. I also see the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as a direct outgrowth of OWS. We’re now having conversations about big corporations, student loan debt, and healthcare debt that OWS helped make mainstream.

You mention your disability and while disability is not a theme in The Not Wives, can you say a bit about how your illness impacts you?

I wrote about it in my essay collection, 16 Pills. It’s called Dopa Responsive Dystonia [DRD], and it’d very rare and often misdiagnosed. It literally occurs in about one in 1.5 million people. I have ups and downs like many of us with disabilities. My brain doesn’t make enough dopamine. I was diagnosed at age eleven. As a child, it was extremely painful; I had tight muscles that left me unable to walk for part of each day. But my parents were very persistent in finding a diagnosis. It turns out to be a genetic disease and my dad, who had no idea he had it, was diagnosed at the same time as me. I now take a medication that is usually given to Parkinson’s patients. In addition, the DRD causes me to experience anxiety and depression, so I take medication for this, too. I feel lucky to have health coverage, but, of course, everyone should have access to therapists, medicine, and whatever else they need.

I wrote about it in my essay collection, 16 Pills. It’s called Dopa Responsive Dystonia [DRD], and it’d very rare and often misdiagnosed. It literally occurs in about one in 1.5 million people. I have ups and downs like many of us with disabilities. My brain doesn’t make enough dopamine. I was diagnosed at age eleven. As a child, it was extremely painful; I had tight muscles that left me unable to walk for part of each day. But my parents were very persistent in finding a diagnosis. It turns out to be a genetic disease and my dad, who had no idea he had it, was diagnosed at the same time as me. I now take a medication that is usually given to Parkinson’s patients. In addition, the DRD causes me to experience anxiety and depression, so I take medication for this, too. I feel lucky to have health coverage, but, of course, everyone should have access to therapists, medicine, and whatever else they need.

I completely agree. You weave some of this into The Not Wives and I found the intersection between faltering mental health, drug, and alcohol abuse, and homelessness to be quite poignant.

Growing up, I had friends who were kicked out of their homes by their families and I’ve lost people to drug use. I’ve seen people struggle. And as a person living in New York City, I’ve always been interested in the kids on the street, with a pit bull on a rope, panhandling to survive. I’ve never looked at homeless people and thought, “That could never be me.” Living in New York is precarious for most of us, and the City is facing an affordable housing crisis. I didn’t want to gloss over this in the novel.

Johanna, one of the books’ central characters, is based on the kids I see everyday on the street, but as I wrote her, I felt hopeful that she would eventually be okay, which is not always the case, especially for LGBTQ kids of color.

In addition, I include a suicide early in the story. A student jumps off the roof of a university building, flying past the windows of an occupied classroom, in full view of many people. Suicide is a huge issue for many universities, for young people, really for all of us. This country is in so much pain. I have not personally seen anyone jump, but I know security guards who have. The young women who dies in the book is the mystery of the novel; we never really know what happened to her.

It’s a really horrible moment, but despite mourning her and wondering about her situation, life goes on. Classes continue to be taught, students continue to study and write, and residents of the City continue to go to work, make meals, protest at Occupy Wall street, and raise their families.

Yes, no matter what else is going on in the world, people continue to get into and out of relationships, get pregnant, and live complicated lives. One of my main characters, Mel, works in a restaurant as a bartender. Restaurants are complex, fascinating places, and while Mel truly loves her girlfriend, she and Stevie, my main character, are both bisexual or pansexual. There are not a lot of novels that focus on this element of life, on ways to be ethically non-monogamous, and I wanted to show them making choices and enjoying their sex and love lives.

Stevie is also a divorced mother and I was intrigued by how she juggles a fierce devotion to her daughter with her desire for an active social and sexual life.

I want people to see Stevie as a mother with a messy and interesting life. The sex is a very intentional part of the book. I want women to have pleasure, to have orgasms. That’s very political for me, especially in this political moment, when the Republican Party is so rigidly policing women’s bodies and our right to health care, birth control, and abortion.

Stevie is recovering from her separation from her spouse and bars are a place she can be free and explore her sexuality. Of course, when her daughter is with her ex, she misses her, but she also appreciates that she has free time and can go out and experience New York’s nightlife again.

She certainly does this! But I also appreciated her portrayal as a working class intellectual, a college teacher without a secure position, because I think that many people assume that college professors live in a rarified and economically privileged world.

As you know, universities have tiers, with tenured faculty at the top, contract faculty in the middle, and adjuncts at the bottom in terms of pay. I’m a contract faculty member with a five-year contract and my job is pretty stable, with health insurance and benefits. Unfortunately, many contract faculty and most adjuncts—the people who teach between sixty and seventy percent of college classes today—can barely scrape by. Most contract faculty and adjuncts work multiple jobs to stay afloat in the city, but adjuncts have the hardest time, often juggling eight to ten classes a semester across a couple of campuses.

Speaking of economic uncertainty, was it easy for you to sell The Not Wives?

No! I started the book about five years ago. All of the characters were in the original version but the story was told only from Stevie’s perspective. I found my agent, Jesseca Salky, from this draft but I then revised the manuscript seven or eight times. Thankfully, I have a high tolerance for deep revision and I learned a lot in the process of making some necessary changes. But I had a breakdown doing it! It was hard. I did learn to write in the third person, which I am really happy about, and I did take breaks when the book was out on submission. The biggest revision, one that took me about eight months, was for a major publisher. In the end, they weren’t able to acquire the novel. Still, by the time it was sold, I knew it was a much better book.

No! I started the book about five years ago. All of the characters were in the original version but the story was told only from Stevie’s perspective. I found my agent, Jesseca Salky, from this draft but I then revised the manuscript seven or eight times. Thankfully, I have a high tolerance for deep revision and I learned a lot in the process of making some necessary changes. But I had a breakdown doing it! It was hard. I did learn to write in the third person, which I am really happy about, and I did take breaks when the book was out on submission. The biggest revision, one that took me about eight months, was for a major publisher. In the end, they weren’t able to acquire the novel. Still, by the time it was sold, I knew it was a much better book.

But you asked about finding a publisher. I have always loved Feminist Press and they were always on my radar. Michelle Tea, the creator of the Press’ Amethyst Editions, is a hero of mine and we have a mutual friend. I asked this friend if she thought Michelle might want to see the manuscript and she encouraged me to send it to her. Michelle loved The Not Wives right away, and the press has been excited about the book since day one. They also understood the Wives and Husbands sections, the most lyrical parts of the book, as integral to the story since they describe mainstream society’s expectations of what wives and husbands should be and what they are in actuality, something that is always complex and contradictory. It highlights that people sometimes chafe at their prescribed roles and the presumed boundaries of gendered life.

Ultimately, Feminist Press has done a great job with the pre-release promotion and everyone there has been really great to work with. I want to give a shout-out to Lauren Rosemarie Hook, my editor, Jisu Kim, my publicist, and Jamia Wilson, the fierce and funny editor-in-chief of the whole enterprise!

That’s so important, and so rare. Will you be going on a book tour when The Not Wives is released?

The book will launch in Manhattan at the McNally Jackson book store and there are nine or ten events lined up after that. It’s going to be intense to do this while teaching and momming. I hope I don’t exhaust myself, but I usually do!

Are you working on any new writing at this point?

In the last year, a poetry collection just sort of came out of me. I wrote most of it on my phone. It’s called My First Queer Year and it is presently looking for a home. I’m always writing essays, too.

Lastly, I’m working on another novel. It’s called Daddy Land and is about a woman who does not yet know she’s queer. She’s estranged from her dad but she goes to visit him in San Francisco because he’s dying and many, many disastrous, and hopefully very readable, things happen to her.

Wow! I’m amazed at your output, along with teaching, mothering, and having a social life.

I’m exhausted, but thank you!