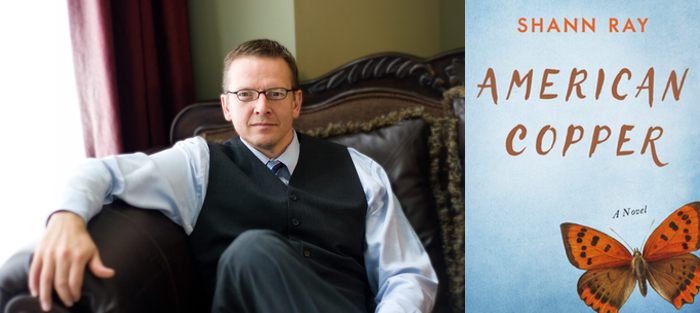

One of the things I crave most in life is the enormous. Seas or storms or mountains. Or feelings. I love it from the trailside or through the windshield, and I love it in the books I read. Five years ago, I came across a collection of stories called American Masculine (Graywolf Press), by a first-time author named Shann Ray, whose ability to conjure the largeness of life—both in the landscape that we inhabit, and in the contours of our heart’s desires—left me scrambling to find new footing in my own life. Isn’t that what the best stories have always done? Sent us back into ourselves for a closer look?

If I’ve always suspected this, I think it’s pretty much irrefutable now, after reading American Copper, Shann’s debut novel, published in November by Unbridled Books. Epic in every way, here’s a book that joins the ranks of the American West’s finest literary achievements without so much as a blush. By turns sensuous and silent and tough and tender, American Copper mines not only the rugged Montana mountains, but the seemingly impenetrable depths of the human heart cast out against the wilderness of the Treasure State.

Shann and I spent several weeks in October of 2015 writing back and forth, trying to parse our ideas on things as divergent as butterflies and rodeos. It was a pleasure to have access to such a thoughtful and wide-ranging mind. And an equal pleasure to be able to share it with you here.

PART I: Forgiveness and Atonement

Peter Geye: I’ve thought long about where we might start this conversation. We could begin with the rich cast of American Copper, which is dynamic and fascinating. We could talk about the tensions between this nation’s history and its treatment of indigenous people. Surely we could talk about love—familial and romantic. And of course we’ll get to all that. But for starters let’s talk about the landscape you set all these qualities against: Big Sky Country, as we ski bums call it. What the world knows as Montana. She’s there on the first page and she’s there on the last. What is it about this place—this huge and mountainous place—that got your attention? And why do you suppose so many folks before you have been likewise smitten? There’s a long list of American classics set against those soaring mountains and grassy plains. Did you have any trepidation entering this pantheon?

Shann Ray: When I think of the literary community of Montana, I feel like I’ve grown up in a family of caring geniuses, all of whom write from Montana as if she is a home of the soul, which she is to me and many. So when I began to conceive of this novel, I thought of it as a love song to Montana and Montana’s people, all her people, and to Montana’s wilderness, as well as an honoring of the great women in my life and my Montana writing mentors. In particular, when I think of Fools Crow by James Welch, Thistle by Melissa Quazny, and This House of Sky by Ivan Doig, I see a trilogy of Montana, mixed of wildflowers, blood, and spirit that animates the kind of global understanding that I believe is crucial in the world today.

Montana, like a microcosm of the country and the world, is also a staging ground for the most ultimate notions of human love and loss. A proving ground for the question of love in the context of the human and the divine. Does love exist? Is there sacredness in people, and in the natural world? These are questions of existence that we all face in post-modernity in the wake of the killing sprees of modernity—Hitler and his 23 million murders, Stalin and his 27 million, Mao and his 50 million. No people or country is exempt. America is positioned at the crossroads of her own genocidal tendencies and the reality of the well-seeded ground in which forgiveness and atonement are hungry for life. The Cheyenne and other sovereign communities such as the Nez Perce and the Blackfeet are leading us to new places as a whole nation, as a community of people in beloved relationship.

Montana, like a microcosm of the country and the world, is also a staging ground for the most ultimate notions of human love and loss. A proving ground for the question of love in the context of the human and the divine. Does love exist? Is there sacredness in people, and in the natural world? These are questions of existence that we all face in post-modernity in the wake of the killing sprees of modernity—Hitler and his 23 million murders, Stalin and his 27 million, Mao and his 50 million. No people or country is exempt. America is positioned at the crossroads of her own genocidal tendencies and the reality of the well-seeded ground in which forgiveness and atonement are hungry for life. The Cheyenne and other sovereign communities such as the Nez Perce and the Blackfeet are leading us to new places as a whole nation, as a community of people in beloved relationship.

When I think of the courage of the Cheyenne, I’m reminded of the courage of people in my country of heritage, Czechoslovakia. My Czech-American grandmother, Catherine, married my German-American grandfather, Herbert, in New York City during World War II. At the same time, their home countries were at war. Germany invaded Czechoslovakia and committed unspeakable crimes against humanity. After the death of Reinhard Heydrich, “The Butcher of Prague,” at the hands of the Czech resistance, Hitler took vengeance on innocent townspeople in Lidice just outside Prague. Lidice was destroyed, all of its men massacred by the Nazi SS, more than 173 men and boys over sixteen years of age murdered by firing squad, Lidice’s women killed or shipped to concentration camps, and Lidice’s children aged fifteen and under gassed to death—eighty two were lost to the gas vans at Chelmno designed expressly for that purpose.

Forgiveness and atonement are always longsuffering, and long in coming. They are earned as much as they are given. My grandparents are dead now, and their legacy is important to me. Their marriage, filled of ranching on the high plains of Montana, square dancing, and a general goodness and dignity shared with the people around them, is an illumination to me personally as a father, a citizen, and a writer.

Speaking of brutality, there is no shortage of it in this novel. Both physical and emotional. Fathers against their children, machines against the earth, cowboys against cattle, knuckles against faces, the white race against Native Americans. I could go on. There are times when the violence becomes an almost physical cross for the reader to bear. Whenever that moment comes, however, you have this perfect instinct to let out a little line, to offer a moment of relief, sometimes even grace. Sometimes it comes via the landscape or an image of the sky. Sometimes it comes with rest. Sometimes an animal offers it. A horse, usually. But the most perfect moments of relief for this reader come in the tender moments when one character holds another character’s face. This happens over and over again, but never indelicately. Quite the contrary, in fact. These characters are reaching out or longing to be held, to find purchase in the closeness of another human being, as if they need the physical proof of another life to orient their own.

Would you tell me how you understand these moments of grace? Would you tell me how they inform the moments of brutality that often surround them?

There is an unforeseen joy when someone whose work I admire so much finds a hidden thread in the novel that I hadn’t willfully named in the writing. I think the idea of touch as a vessel of restoration dates back to my experience of family, and how touch can infuse families—and, in fact, nations—with the will to love. In brutality, the loving touch is turned to its most evil counterpart: violation, rape, even eradication. This ever-present evil, in ourselves and others throughout the world, requires an answer, and, in fact, transcendence. Such transcendence makes huge demands of us, in our families, our communities, and from nation to nation.

Martin Luther King, Jr. said:

Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.

He also said, “Hate cannot cast out hate. Only love can do that.” I believe MLK’s wisdom. I believe it finds affirmation in each of us, in our hands, our bodies, our touch, when we encounter the grace to experience it fully.

The recovery my generational family has gone through teaches me that, and the unwarranted elegance I’ve received by living with a great woman, my wife, Jennifer, and my three daughters, Natalya, Ariana, and Isabella. Jennifer used to hold the heel of each of our daughters as they nursed and slept in her arms when they were babies. MLK speaks of what Emerson called the Oversoul, a unifying strength we are responsible for as individuals and communities. He echoes many who have informed my life as an artist: Dickinson, Whitman, Veil, Arendt, Gadamer, Bonhoeffer, hooks, Wiman, Fujimura, Romero, Gaudi, Lorca, Milosz, and writers like Morrison, Silko, Welch, Momaday, and Erdrich. They are unafraid of the sacred. In effect, by loving deeply they show us that beyond nihilism and our genocidal history, love exists, the sacred exists, and finds expression through touch, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. This touch, I believe, heals us, heals our hearts, our rifts, and the chasms of inhumanity that often stand between us.

In my doctoral research I completed a hermeneutic phenomenological study using in-depth interviews with people who had suffered great harm. I wanted to learn more about the essence of touch and forgiveness. Their stories shattered me. The beauty was so present and had such power it made me think differently and live differently. I wanted to live more toward the atonement-making ethos that we now recognize in crucial places throughout the world: in the Native American ceremonies around healing the trauma of our shared American history; in South Africa in response to Apartheid; in the Philippines during People Power 1 and 2; throughout Europe in response to the degradations of WW II; in Colombia with the restorative justice process drawing perpetrators and victims together toward legitimate restoration; in every corner of the known world.

As you mentioned, sometimes literature has an almost physical cross for us to bear as readers. Viscerally, in our bodies, we share the anguish of our history whether we consciously recognize this fact or not. It makes me question: What can we do with our brutality? Does forgiveness call to us? Is there an atonement we can surrender ourselves to that will lead us back to one another? These questions and others bring me to the art of the novel, which I see as the art of being a person with other people. Legitimate touch, in the context of legitimate love has been so important to me personally, in my life with my wife and daughters, in my friendships and with my larger family. I think it just seeped into American Copper and the three main characters’ experience of the anguish and ecstasy of life.

My goodness, man! You speak with such elegance and softness. I love it when a man who knows so much talks in what is surely a whisper. I wonder if you think that perhaps you’ve written against this long history of ours in the form you have because the Novel makes the suffering of our people somehow more manageable. If the Novel is somehow a better vessel than a history book, say, because it allows for more nuance, and certainly it makes the scale of that suffering more tamable.

What I mean is, a novel requires a kind of intimacy and focus that larger histories have to work against. As someone who’s obviously read copiously of our past, do you think that’s fair to say? Why did you choose to address these themes and this range of suffering in a novel as opposed to another vessel of literacy?

I love all the vessels, my friend! I feel immense gratitude when the vessel of poetry, or history, social science or creative nonfiction, painting, dance, sculpture, or the novel lead us back to a more whole and more deeply-imagined sense of the soulfulness of human connection. That said, the panoramic sweep of the novel, and the intricate creases on the very hands of those who people the novel, creates a dynamic helix of call and response from writer to reader and reader to writer that speaks powerfully, in a whisper, in a shout, of the intimate nature of how art works its way into the blood of our being and has the capacity to anchor us in ultimate Being (as the great Czech presidents Masaryk—a renowned philosopher—and Havel—a powerful playwright—remind us). Dust returns to dust, which is the way of all flesh. Death is perhaps the most natural or Nature-infused door into a more fertile, more life-filled wilderness. For me, this open-armed receiving of the loving embrace leads me through the struggle and entanglements of my doubts of the infinite and eternal, and transports me into what I experience as irreducible love, or ultimate Love… love that heals us and helps us atone for our atrocities, restoring us to one another.

You teach in the Leadership Program at Gonzaga University, with an emphasis on the nature of forgiveness. Good Lord, but I hope you have a thousand students. And I hope they’re all learning what you teach. It seems the world has never been more desperate for forgiveness. Each of us, daily; but all of us taken together, too. I often wonder at the violence of the earth. The wars and the killing and our willingness to abhor others. Is it the most despicable time on earth? I doubt it, though it sometimes seems it must be.

As people I believe we have always been despicable, and we have always been beautiful. The reconciling of these polarities within our individual and collective life is too complex to fully name, but when someone begins to name it in our presence I believe it illumines our most graceful desires, our most holistic longings.

Just so, there’s an incredibly powerful moment relatively early in American Copper when William, coming of age, is reminded by his father of the battles between his people, the Cheyenne, and the soldiers and settlers they so often battled. The elder Black Kettle’s concluding thought is that, on this glorious morning, they should “[R]emember our history, a history we share, Indian and white. Today is a good day to forgive.”

This is but one moment of extraordinary insight into the experience of the Cheyenne (and the other Native American tribes you write about in this book). I wonder if you ever felt like you were trespassing on an experience too far outside your own? Were you ever worried that in representing these lives, you had crossed a boundary?

It also seems inevitable that you must have drawn on your own scholarship to write these lives into being. Did you? And did you come out on the other end of this novel with an evolved sense of the white settlement of the territory of Montana? Or of the suffering of the Native Americans? Or, most importantly, on the essentialness of forgiveness?

I love your questions, Peter, and this one takes me back to the time I spent as a boy on the Northern Cheyenne reservation in southeast Montana. I’ve never been so sifted and shaken, so hated, and so loved, before or since. That love stays with me, from Cheyenne friends like Lafe Haugen, Russell Tall Whiteman, Cleveland Bement, and Terry Curly. I often feel I’m trespassing or transgressing boundaries as an artist, and this is painful to me. How does a man write of a woman or a woman write of a man? Do we even know ourselves to the depth we should? The incomprehensibility alongside the humble desire to know and be known is a foundation stone for me when considering gender, race, class, culture, belief, and sexuality. Dignity, listening, and vulnerability come to mind. I don’t know that we can truly do justice as artists to one of the most exquisite elements of the natural world: people. But we try. With all of our heart, we try.

Scholarship came into play, but mainly as an underline to the relationships in my life with Montanans, Northern Cheyenne and white, and infinite in their individual and collective difference and shared sense of humanity. I went back to people like John Stands In Timber, Paula Gunn Allen, Dee Brown, and James Welch. But more readily, I went to my friendships and tried to honor them. I hope the novel honors Montana’s people, her first people and those who came later.

The Cheyenne way of leadership, traditionally, gives a sense of honor: honoring elders and children, women and men. No tribe is perfect, be it Cheyenne or Czech, German or American. But some ways of being are more mature or more whole than others. I remember the Cheyenne ceremony of healing, a dedicated run over the land where the Sand Creek Massacre occurred is an example of culture healing culture. People transcending a history of hate from dominant culture with a life of love from their own culture. I think of the Czech ceremony in which the children of Germany were invited to Lidice to plant 100,000 roses with the children of Czechoslovakia, how it gives us another way to envision our former brutality. Roses were sent for this purpose from countries around the world. I’ve been to Lidice. A place with such a gruesome history of death and genocidal atrocity, and yet the Garden of Friendship and Peace imbues the land and our memory of it with sacredness. I consider the Nez Perce reconciliation ceremony at the site of the Big Hole Massacre in northwest Montana, where the descendants of the U.S military who performed the massacre are invited to sit in sacred ceremony, a ceremony of peace, with the descendants of those who were massacred. That ceremony is among the most vital global leadership endeavors, calling us to greater wholeness. Massacre sites can be places of atonement. Can America become such a place with regard to our history of slavery, genocide, and human rights violations? I hope we can. Reparations will be an important part of that atonement.

Our nation is not alone. Worldwide we rage. We are manipulative. We do violence. One of the most prescient questions of this age or any age is whether or not ultimate forgiveness counters ultimate violence. Our history is replete with annihilation. And yet history also rings with mercy. The divine notion that mercy triumphs over justice is another mystery I don’t understand. I want to understand it, but I don’t feel I can quite grasp the meaning. There is evidence from science now, compelling and far-reaching. People with higher forgiveness capacity generally have less anxiety, less anger, less depression, greater emotional well-being, and in one of the most telling social science discoveries of the last century, less heart disease. Bridges are being made through forgiveness to stronger immune systems. The Mayo Clinic uses forgiveness as a therapeutic treatment plan with cancer patients. The bridge is not yet complete but I believe sooner than we think, it will be.