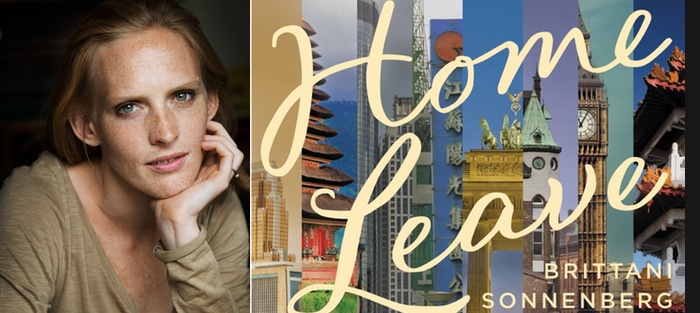

I first met Brittani Sonnenberg several years ago, at a party a few days before beginning the MFA program at the University of Michigan. We spoke on and off, in the way that you do in rooms where no one knows one another, in nervous and elated starts and fits that attempt to understand a new person. Later, I said to my husband that Brit was either nineteen or forty-five; I couldn’t tell (and hadn’t asked). She exuded a worldliness that came from experience, yet underneath was a genuine sweetness. While many people who have lived interesting lives are eager to list their backstories as accomplishments, I had to ask questions to learn that Brittani spoke fluent Mandarin and had worked as a journalist in Cambodia. She lapsed into a Southern accent at times. Her laugh came from a real place. I knew nothing yet of her expat childhood, of her Harvard education, of her sister’s death when they were both teenagers; these facts I learned from both our friendship and our years as readers of each other’s work. Hers was infused, like Brittani herself, with worldliness and openness of heart.

That her debut novel, Home Leave (Grand Central Publishing), would catapult readers from Georgia to Singapore to Germany to Wisconsin, that its territory is at once the whole world and a family unit of four, was no surprise to me. And yet, Brittani has done more than simply write what she knows; the book refreshes form and voice with every chapter, each one a stunning act of disorientation and re-orientation that takes us deeper into the hearts and histories of the Kriegstein family as they relocate and settle with varying degrees of enthusiasm and trepidation. Home Leave doesn’t traffic in exoticism; there isn’t a lush landscape or heartbreaking beggar child to be found in its description of foreign places, nor in its portrayal of the Kriegsteins, a family that has worked so hard to be each other’s center as they chase opportunity and adventure, only to be cracked open by a shared and isolating grief when the younger daughter, Sophie, dies unexpectedly as a teenager. The book sharpens your comprehension of tragedy from the inside out while also being, often on the same page, achingly, laugh-out-loud funny.

Brittani and I had this conversation on The High Line in New York City, the city where I now live and she’d recently given a reading. When I transcribed the recording, listening to our conversation amongst the birds and the white noise of foreign tongues around us, it occurred to me that The High Line, a place where you can’t tell the natives from the visitors, was the perfect starting point for a conversation about a book that asks how one maintains a sense of home despite constant disorientation. We continued our conversation on FaceTime, time zones apart. I’ve edited for clarity, but also to remove the many spaces of laughter and our tendency to step into each other’s sentences. In the pages of Home Leave, too, is a cast of characters who all want to speak, to partake in the conversation, who finish each other’s thoughts and stories, who make those stories stronger and deeper because of their connection no matter where they are in the world.

Interview:

Danielle Lazarin: I wondered if the tradition of storytelling is in your family, or is that just a myth I believe about Southerners, that they like to sit around and tell stories?

Brittani Sonnenberg: No, that absolutely is in my Southern side of the family; it’s a big tradition, and it’s what they do around the dinner table, and even stories that everyone’s heard a billion times get told over and over again and are hilarious and funny and moving all over again. It always seems like that was a natural mode and that there was also some kind of inquisitiveness in their digging in that material over and over again.

Did you get only the funny stories, or also stories like the way the book opens, the story of Elise’s past abuse? Would that kind of story be pushed under the rug?

The scary stories, or the hard stories to tell, were not told in that way, but there would be a sort of hovering around the material in some ways; there would sometimes be jokes around it. I’m not referring to the story with Elise, but just things that were darker in general. I think humor lends itself to that kind of shadowy realm, too—sort of putting your toe in it with a joke and then ducking back out. Sometimes the laughter comes from that thrill of being on the edge of that darker stuff, and then the relief of stepping back, which prompts the laugh. I think what separates writing from storytelling around a dinner table is the depths you can plumb and not having to step around that stuff.

The book’s humor definitely walks with that darkness you’re describing—it’s a risky pairing. I was thinking about this also with the publication of your short story “Hong Kong Buffet” [published in book form by Readux Books], which does that as well. Is “funny” something that you’ve always done? How do you know when it’s too much?

A thing that helped a lot was being in an improv comedy group at Harvard. When we were doing scenes we’d try to land on funny, but by no means were we trying to avoid harder stuff. When we did long-form shows there would be narrative arcs throughout everything, and one of our goals was to create characters in situations that worked beyond just the comic, which was the lens through which we were telling the story. That really helped me with writing. I don’t think until I had that training that I thought of myself as someone who could be funny. There was a realness in humor that I appreciated.

In terms of trying to gauge when to step back from it, I try to make it character-based so that it’s also about the character’s level of comfort with what they’re trying to say. Sometimes that comfort level influences how they’re telling the story; maybe they’re going to hedge a little or go for a joke as a defense mechanism. The humor in “Hong Kong Buffet” is a lot of cultural mishmash, but it’s also about yearning and wanting and the comedy in that, a pathos of desire and when it falls short of expectations. What I appreciate the most when I read things that are funny is humor that doesn’t make fun of the characters. It’s either them telling the jokes themselves or it’s a very kind of generous loving laughter with them, not ever against them.

I loved how the story didn’t necessarily belong to one person the way grief doesn’t belong to one person in the novel. How did that decision come about? Did you consider using a single perspective?

The only thing I really thought from the beginning was that I wanted to set a different chapter in a different location. I just thought I’d follow the geography and let the setting predetermine the voice. When I would finish one chapter, I would feel a kind of craving for a new voice; it felt like there was someone who could really talk about Philadelphia, and sometimes it’s the way that people are at a dinner table—especially couples who are competing to tell a story, and they demand that it be handed over for the part they can tell well. The Thailand chapter is told in alternating first-person between Chris and Elise; they had that couple dynamic: “I want to tell my side, too,” or “Look at it over my shoulder.” Also, because I knew the general trajectory of what was being told, I felt like I needed a way to stay curious with the material, and so every time there was a new chapter—and maybe this is also true if you are a short story writer—there’s that impulse to make each chapter new. I really wanted a fresh approach to the material and changing voices felt like that helped.

The only thing I really thought from the beginning was that I wanted to set a different chapter in a different location. I just thought I’d follow the geography and let the setting predetermine the voice. When I would finish one chapter, I would feel a kind of craving for a new voice; it felt like there was someone who could really talk about Philadelphia, and sometimes it’s the way that people are at a dinner table—especially couples who are competing to tell a story, and they demand that it be handed over for the part they can tell well. The Thailand chapter is told in alternating first-person between Chris and Elise; they had that couple dynamic: “I want to tell my side, too,” or “Look at it over my shoulder.” Also, because I knew the general trajectory of what was being told, I felt like I needed a way to stay curious with the material, and so every time there was a new chapter—and maybe this is also true if you are a short story writer—there’s that impulse to make each chapter new. I really wanted a fresh approach to the material and changing voices felt like that helped.

How did it feel to write what is, in some ways, your parents’ story? I’m curious about this instinct that as writers we often feel this ownership of our family stories.

Well, I also felt like those were some of the most fictionalized parts. I had grown up knowing how difficult it was sometimes for my mother when my father traveled for work. I was curious what it felt like for someone in her shoes to look forward to the husband leaving and starting to take these kind of secret trips herself as a way to examine a parallel universe to my mom’s own story. I think all of us have these parallel universes simultaneously running. With the chapter with Elise in Germany, it was a real blend of our perspectives—me living in Germany and imagining what it must have been like for her—and then this bizarre thing happening that had happened to neither of us. But I think because the character was such a hybrid, it allowed for a totally new thing to happen that wasn’t autobiographical for either of us.

It sounds like you made your parents characters and that probably kept you feeling safe while you were writing it, that allowed you to write it rather than report it.

Yeah, and that goes back to that sort of curiosity. It wasn’t just worrying that they would be really hurt, or them feeling like I had crossed boundaries if I had told one-to-one what their story was, but that it wouldn’t be interesting enough. I wanted to write a new story.

I can’t help but think about how this curiosity for newness might mirror a curiosity to live in different places, a drive to move from one thing to the next and your openness to it. I think the book’s form is very risky, especially for a first-time novelist. Do you see any link between those two things?

I guess I do in some ways, which is that I have the feeling that it was the only book I could write with that material. Sometimes as I was writing the book I was so frustrated that it wasn’t coming out more traditionally because I felt like it might be too confusing for readers; I understood why those jumps occurred for myself, for the characters, and thematically. But, yeah, I wasn’t always really excited that that was happening.

Which may or may not mirror your own experience, right?

Yeah, right, exactly. With new homes and new places, that kind of sinking feeling of what have I gotten myself into?

I think you did a beautiful job mirroring the disorientation of the characters without disorienting the readers. Which is interesting because you said that you think curiosity is also from having been raised as a short story writer; often what people complain about with short stories is that they have to enter a whole other world when they reach the next story. Usually in a novel you create one world and you can move your players around, but part of what’s essential to your book is constantly uprooting and reorienting those characters.

Right. And at any one time their worlds are really stacked within them quite inarguably. Even the way Sophie and Leah talk to each other. My sister and I would use German words that our parents would drop into the conversation or remember liverwurst from England; in our dialogue with each other were all of the places at once. It was so important for everything to be there, for it to be a crowded geography.

I’m sitting next to this book, Imagine (Jonah Lehrer, Houghton Mifflin), and I keep thinking of you, because there is a section called “The Outsider,” which talks about how people who live abroad and travel are more creative. I thought of you, how being able to adapt to different places does probably inform your ability to write and examine different ways of living and different ways of crafting a story. I wonder if that’s something you’re conscious of, if living in different places informs your work.

I don’t feel like I’ve quite absorbed forms from anywhere else, because I’ve never been fluent enough to be able to read in another language in any of my childhood homes. So I’ve never been able to say, “Oh, yes, Tang poetry, definitely, that’s why I wrote Chapter 8.” But I do think that there’s… I was about to say “impatience,” but that’s not quite right… I remember the feeling I had when I started to write the first therapy chapter that’s written as a play and wanting for it to be a completely new landscape. I wanted something that made me feel the way when you step off a plane somewhere in a totally new place, and you just have to fumble and draw on your best resources to meet the place head-on. I think sometimes I do have a real craving or appetite for those strange places and for feeling new in them and the thrill of feeling new in them. So that probably did go into it. I really like thinking about that. A neat question.

Speaking of place, you visited a number of the places in the U.S. that are featured in your book during your recent book tour. And your mother was with you, right? I love the image of you and your mom on that Southern road trip. What was that process like?

It was amazing. Because if I’m really cavalier about going to new places then I’m also quite shy sometimes about returning and about reunions. I feel like once I’ve left a place, I’m nervous about how to maintain connection. I maintain connections through writing but not necessarily through relationships or visiting the place regularly. All the places we went together in the South my mom was so great about telling everyone about [the book], which was so moving. It was so great to see people from that era. And also just to be in the humidity of Atlanta or Mississippi; it’s so specific and it felt really right with the book just to be back there. And in New York, seeing so many writer friends from our program, remembering that writing community; I felt really humbled by it. There was a lot of time in the car to process and to talk. I read the first chapter in Oxford. That was insane and great. And we listened to that Brad Listi interview [on Otherppl].

Really?

Yes, and I was like, “I’m sorry I swear so much; I don’t know why I swore all the time.” Good lord.

I love how the book ends, leaving the family in a stage of grief still, which feels like the truest ending. As one character asks, “Who knows what the next level is?” Did you ever feel like you wanted to end with an answer rather than a question?

I was surprised at how each chapter developed and that everyone was clamoring to speak in the last one. Especially Sophie’s voice at the end—that was the most surprising thing to me at all, that she came in and that she in some ways was the most clairvoyant. I mean, you know, it makes sense, too, because she is sort of in another state. But I was surprised that she was the settling voice, even though she’s talking about other levels like video games, because she’s still kind of thirteen.

She’s a teenager. I appreciate that you didn’t make her super-duper wise. Our culture of grief expects that you get over it, then you move on to a place of clarity, and I feel like this book speaks against that in a way that’s so far from tragic. The characters don’t end in tragic places.

I think they are all enriched is the wrong way to say it, but it’s kind of like there’s another country that they’ve all spent time in, and I don’t think any of the family members would take away any of the places they’ve dwelled in. And, of course, they would try to bring Sophie back, but I think that they’re all more human and just…

Trying to figure out their next level?

Yeah. Through that experience of deep grief.

Lastly, would you talk about your process of finding an agent and getting the book published, as well as its various incarnations? This book was not the book you thought it would be initially.

In some ways it was a really long process. After a certain point it went fast, but there was a lot of build up to it. I had one agent that I had found through a family friend and I was so relieved to have an agent. But after a year we were trying to go out with a short story collection, and it wasn’t working, and I felt that we weren’t the right match. Then I found Jenni Ferarri-Adler [at Union Literary], who I had gone to graduate school with, and deeply trusted from knowing her. She cared about the writing, but also really understood it and was a great reader, too. I had showed Jenni the short story collection and then Jenni heard about the two novel ideas I had and encouraged me to write the one. I had also written a memoir, which I was less sure about. Jenni liked the idea of taking some of the material from the memoir and re-approaching it through fiction, which I had already started to do a little bit. I also got so much energy through having this new agent, who I really felt was waiting on it and encouraging; that’s the period where it started to feel like it just went really fast.

It sounds like this material was always kind of waiting for you, and it was finding the form and finding the person that helped you to recognize that this was the book.

Yeah, and that’s a good thing to remember, even now. Just how much is going on all the time, you know, for the writing process, that you don’t even think about.

I think about that a lot, actually—the things you think are insignificant, and then years later, find their way in. The way those little things are stored in you and you kind of can’t shake them out, and the way, to a writer, they’re useful whether or not you know you’re using them.

Yeah. And I think there’s a ripening process. It’s like tugging on an apple or a piece of fruit and it won’t budge, but then another time you’ll go back and it will just fall right off.

Or, hit you on the head.

Or hit you on the head!

Hard. And then you’re like, duh! This was my book.

[Laughter.] Eureka!