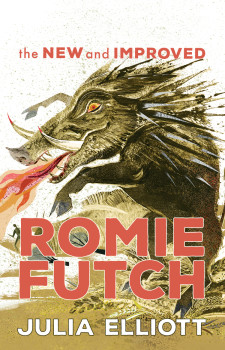

Julia Elliott’s first novel, The New and Improved Romie Futch, out last month from Tin House Books, is already seeing the kind of acclaim that met her debut short story collection, The Wilds—also a Tin House title—last year. That collection was praised by Kirkus, BuzzFeed, Book Riot, Electric Literature, and the New York Times Book Review, and included stories anthologized in Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses and Best American Fantasy.

The desire for deep and real connection—between characters and each other and characters and their own humanity—draws me to Elliott’s stories. Her writing is also jam-packed with the absurd, the fantastic, and the absurdly and fantastically true. The breadth of knowledge on display in her short stories can be found in her first novel, as well, and is one of the many joys of reading The New and Improved Romie Futch. In fact, her protagonist, Romie, is the locus for much of that knowledge. His life in a tailspin (too much drinking and too little promise), and bored with his taxidermy, Romie agrees to let a shady Center for Cybernetic Neuroscience upload works of philosophy, theory, and literature—great and small—directly into his brain. The result: his taxidermy takes on new life in theory-inflected dioramas, the future holds promise, and he becomes obsessed with, among other things, Hogzilla, a terrifying mutant swine in the South Carolina backcountry. Yet, all of this is realized in detail that makes the landscape of the novel seem like a place we all could be living in a few years from now.

Because of my admiration for Julia’s work, I was ecstatic when she agreed to write a story for Found Anew, an anthology that I was co-editing with Ray McManus, which the University of South Carolina Press just released. We asked writers to dive into historical image archives recently digitized by the South Caroliniana Library, and she found a haunting picture of a room awash in light and drew from it the kind of soulful, gripping, often harrowing narratives that I always meet when I read one of her stories. She saw the hidden potentials and perils in the picture that she is able to see in tabloid stories and scientific advancements, in spa treatments and debilitating conditions.

On a windy day, we met at Drip, a coffee shop in Columbia, South Carolina, to discuss her new book, her process, and how baboons guide her writing life.

Interview

R. Mac Jones: So, what’s new?

Julia Elliott: Well, I’ve got a story out in Best American Short Stories 2015, which I couldn’t believe until I saw the book with my own eyes. I just got my hands on a copy and can see that, sure enough, the story’s actually in there. So, now I can officially tell you I have a story in Best American Short Stories. It’s called “Bride,” and it takes place in a medieval convent.

This, along with my Found Anew story, “August 1886,” inspired me to think about historical fiction in a new way. I’ve got this medieval convent story, and then I’ve got this 19th century story, so I started envisioning a collection of what we might call postmodern historical lit. Writing the story for Found Anew started the idea for me. And I’ve been thinking a Cleopatra story would be cool, but the main character would be a woman in the 1970s playing Cleopatra in an experimental film, stranded on the island of Cyprus with a bunch of freaks, the whole crew stuck there, attempting to film that famous voyage that she supposedly made to Greece in her beautiful gilded boat. But instead it’s about the actor who’s playing her, with a bunch of, you know, 1970s psychedelic musicians and actors, and the director would be sort of Jordorowsky-esque.

This, along with my Found Anew story, “August 1886,” inspired me to think about historical fiction in a new way. I’ve got this medieval convent story, and then I’ve got this 19th century story, so I started envisioning a collection of what we might call postmodern historical lit. Writing the story for Found Anew started the idea for me. And I’ve been thinking a Cleopatra story would be cool, but the main character would be a woman in the 1970s playing Cleopatra in an experimental film, stranded on the island of Cyprus with a bunch of freaks, the whole crew stuck there, attempting to film that famous voyage that she supposedly made to Greece in her beautiful gilded boat. But instead it’s about the actor who’s playing her, with a bunch of, you know, 1970s psychedelic musicians and actors, and the director would be sort of Jordorowsky-esque.

When I wrote “August 1886,” using that image [of a room awash in light], I thought, “This is a weird room. Who’s in this room?” So I started thinking about the kinds of quacks and mesmerists who would come to a drawing room like that. They’d perform strange pseudo-medical procedures on people. The convent story, “Bride,” is a medieval story, about a female mystic—I used to read a lot of that stuff when I was in grad school: you know, all those crazy Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe type narratives.

As much as the mystical, you write about technology. What are the connections there for you?

The connection for me is the cultural history of science. In grad school I read a lot of Renaissance gynecology and obstetrics works and discovered that they are insane; they are like magic realism or something: monstrous births, weird reproductive theories, melancholy, all that stuff. When barber surgeons started to do anatomy theatres, it all got a little more “scientific,” as we think of it today, but was still brutal and culturally loaded. If they had a woman out on the anatomy table, for example, you could pay admission and go and watch, and the anatomist would say things like “Behold, here is the uterus, the origin of sin and death,” and then he would dissect it. Here, cultural ideas about femininity are obviously mixed in with the supposed science.

The language is still religious.

Yes, and even in the nineteenth century science is very strange and full of weird theories about women and Darwinism twisted into every possible permutation. The “scientists” brought a lot of cultural baggage to their research, and I think we still do that today. I feel like every era has a way of seeing the world that they think of as objective, advanced and scientific, but science is always profoundly cultural.

So, this seems to naturally lead into a question about influence. When you are putting together a collection of short stories that you have written over years, you probably can track how what you were reading guided what you were writing. Do you immerse yourself in reading, or avoid reading certain things, when you are in the middle of writing something?

I never avoid reading—reading the words of others fuels my own verbal output. By this point in my life, I hope that I’ve read enough to avoid channeling the style of whatever book I happen to be reading. Instead, a good book rekindles my love of language and gets my brain stoked to wordsmith. Although I do pick up new tricks from every good book I read, I don’t suffer from the so-called anxiety of influence. Somehow, every time I returned to Romie Futch, even after month-long interludes, his voice popped right back into my mind, as though my inner hesher-warrior had been stewing in my unconscious, raring to burst back out onto the page. [For those new to the term “hesher” as a subculture, Julia has described them to me as the “high school, weed-smoking metal-head slackers who might’ve been lucky enough to drive a Camaro or its ilk.”]

The novel hinged on the right voice. Before, you noted that “August, 1886” came from wondering about who would have been in a particular room.

Stories come to me differently. Sometimes a satirical concept will come first. For example, “Regeneration at Mukti,” that story set in a spa, came from getting poison oak when we lived in Saluda, North Carolina. My arm transformed into a pus-filled, bubbly, yellow mass, and then it crusted over. And I thought, Oh my God, I’m going to be scarred for life. Then, after it healed, my skin looked pretty good, maybe even a little bit better from the healing process. And I thought, What if a spa took nanotechnology and combined it with homeopathic approaches? And this made me think of people who go on plastic surgery safaris, drinking in the beauty of nature while their face-lifts heal. So, “Regeneration at Mukti” is a satirical and ridiculous spoof of pseudo-zen spa culture, where vanity is often disguised as a spiritually motivated quest for self-improvement. The whole process was different for my story “LIMBs,” which was inspired by the story of a friend whose grandparents were both in a nursing home at the same time. One had Alzheimer’s and one did not, and they were kept in separate rooms. I thought that was the most harrowing situation ever—to spot, toward the end of your life, the person you’d spent your life with, in the cafeteria of an impersonal institution. So, then I had a vision of a futuristic nursing home and a woman on robot legs pushing her elderly husband in a wheelchair down an empty highway. That story sprang from a kind of imagistic vision. Sometimes these images come in an epiphany-like, smack you, kind of way, and other times from a very cerebral idea.

Stories come to me differently. Sometimes a satirical concept will come first. For example, “Regeneration at Mukti,” that story set in a spa, came from getting poison oak when we lived in Saluda, North Carolina. My arm transformed into a pus-filled, bubbly, yellow mass, and then it crusted over. And I thought, Oh my God, I’m going to be scarred for life. Then, after it healed, my skin looked pretty good, maybe even a little bit better from the healing process. And I thought, What if a spa took nanotechnology and combined it with homeopathic approaches? And this made me think of people who go on plastic surgery safaris, drinking in the beauty of nature while their face-lifts heal. So, “Regeneration at Mukti” is a satirical and ridiculous spoof of pseudo-zen spa culture, where vanity is often disguised as a spiritually motivated quest for self-improvement. The whole process was different for my story “LIMBs,” which was inspired by the story of a friend whose grandparents were both in a nursing home at the same time. One had Alzheimer’s and one did not, and they were kept in separate rooms. I thought that was the most harrowing situation ever—to spot, toward the end of your life, the person you’d spent your life with, in the cafeteria of an impersonal institution. So, then I had a vision of a futuristic nursing home and a woman on robot legs pushing her elderly husband in a wheelchair down an empty highway. That story sprang from a kind of imagistic vision. Sometimes these images come in an epiphany-like, smack you, kind of way, and other times from a very cerebral idea.

You mentioned Jodorowsky before. Mysticism and esotericism figure prominently in his work. Do you see similarities between your work and his? Are your stories what you would call surreal?

Most of my stories are surreal, and though I love Jodorowksy and have been inspired by his dream allegories and visual wonders, not many of my stories evoke his particular brand of surrealism. Meemaw’s lurid end-time visions and modest levitation in “The Rapture” probably come closest to Jodorowsky’s mystic phantasmagorias.

What did you have to give up that was comfortable about your writing process to write The New and Improved Romie Futch?

Writing short stories, for me, has a more organic feel to it. And I don’t try to put what you might describe as a more cinematic plot into short fiction. Stories blossom more thematically, I suppose. They have characters and a sense of place, and these elements often form the core if the story for me. Obviously, things happen, but I don’t feel like I have to put in the cinematic plot element. But with Romie Futch I had to plot more fiercely and try to make convincing connections between various sub-plots.

Do you sense that when you read novels, other people’s novels?

Yeah, and I know that from hearing writers talk, like in The Open Book series here at USC [the University of South Carolina], because they’re usually very honest about their process. They will talk about the giant heaping mess that was their novel before they made it into a streamlined narrative. That’s what I’m talking about. With Romie Futch, my editor helped a lot, too. She wouldn’t tell me what to write, obviously, but she would definitely point to events and themes that could be connected to other events and themes, creating the kind of plot momentum that’s typically not in my short stories.

So, why move into novels now?

Romie Futch was actually written as a short story that got too big for its britches. It was full of big ideas and an endless wild hog chase, and in a short story that was just ridiculous, so I forgot about it. About six years later I read this article by my cousin Carl Elliott called “Guinea-pigging,” originally published in The New Yorker. It’s part of his book about the medical-industrial complex and Big Pharma, and it’s all about guinea-pigging culture: people who serve as test subjects for money and do it as a career. It’s like a dark underworld. They sometimes do it in seedy hotels and strange, broken-down facilities. There’s even a ‘zine for guinea-pigging. It’s a fascinating culture. So, I began to think about making the research facility a big part of the novel, and then The Center for Cybernetic Neuroscience started to take shape as part of the plot. All of my attempts at novels before Romie were more like big, fat short stories that tanked. This one had some movement because I had the original short story there to guide me. Another thing I did was make the main character younger, because he had been in his fifties in the short story version. By making him an ex-hesher type, I could relate to him culturally. I had been thinking “older, country guy,” then I decided, no, Romie is the kind of hesher I went to high school with.

With such a different process for writing a novel, how long did it take to write the first draft of Romie Futch?

I wrote the bulk of the first draft during my first pregnancy (in around eight months), and it’s ironic that I channeled my inner macho-hesher-warrior when my estrogen levels were at their highest ever, a female fetus forming within. After I had my daughter, I finished the final third of the narrative in about four months and then went through two revision processes: one with my agent and one with my editor at Tin House.

I wrote the bulk of the first draft during my first pregnancy (in around eight months), and it’s ironic that I channeled my inner macho-hesher-warrior when my estrogen levels were at their highest ever, a female fetus forming within. After I had my daughter, I finished the final third of the narrative in about four months and then went through two revision processes: one with my agent and one with my editor at Tin House.

Did you find the process of writing the novel enjoyable? I don’t want to say “fun.”

After writing two novels that failed due to lack of momentum, this one actually was “fun” to write, partly due to the absurdity of the character’s situation. Although writing can be difficult, when it’s going well, it has an opiate effect on me. To me, one of the purest forms of happiness is a clear mind, a cup of coffee, and the “right” words streaming onto the page (inversely, a cloudy brain, ineffective caffeine stimulation, and stilted writing depress the hell out of me).

The revision process, which I had always thought of as painful, became kind of miraculous, partly because of how well I worked with my editor, Meg Storey. I began to think of revision as a way to unlock exciting narrative secrets.

What guides it all? How do you know what miracles you want to perform with fiction? I guess I mean, do you have a larger project that guides all of your fiction, some intention behind why you write what you write?

I think you learn what you think through writing. You have these hazy ideas about the world and spirituality and earthy reality and science and the body and all that, and when you put them into language they take shape for you and for readers too, hopefully. But, I don’t think I have a coherent all-encompassing philosophy that guides me. Nevertheless, I do have a baboon obsession. Ever since I was a grad student at Penn State, I have been trying to write this baboon novel, and I’ve started it about three times. The first version was my Master’s thesis, which is so experimental that it’s incomprehensible. And then I tried to write it again about seven years ago and that didn’t work, and now I am finally writing the “real” baboon novel. Baboons may even have some deep spiritual meaning for me—Hamadryas baboons. I did research them, spending an entire summer at North Carolina Zoo with them. I sat for hours at their enclosure. The baboons were behind a Plexiglas wall. The smells were psychedelic. For me, my most obsessive endeavor has been attempting to write that novel, and it took me the longest time to figure out how to write it or how to become the writer I needed to be to write it.

Do you think that is from finishing this other novel?

Yes. Yes, and don’t forget that I wrote a couple of failed novels before the one that got published. Romie is an outrageous romp, even though it is also dark and has these questions about the nature of reality in it, but there’s also a lightness of tone and a satirical element. The next novel is more serious, I suppose, although, it does have some humor. I’m just a silly person, probably.

Does that help the writing itself, though? Would you not be able to do it, if it became too serious?

For me, there is always either a comic or a dreamy element to what I write. I feel like the ridiculous is one way to approach the sublime. Although I love serious novels, novels like The Road, I could never write that kind of novel. I admire people who can achieve that sort of tone. Maybe when I’m a bit older, maybe twenty years from now, I can write a haunting, sober novel.

I think it would be your choice of subject matter, too. The end of civilization lends itself to dark tones. As long as you have this focus on technological advancements, there does seem to be something inherently ridiculous, to use your word from earlier, about the ways in which we try to cobble together a means to fight that end.

Yes, and it’s me. I have the silly side and the dreamy side. The title story from The Wilds has that dreamy, romantic quality to it. But my baboon novel has a range of tones. It’s Kafka-esque, I guess, because, for me, the dreamy, surreal stuff that I like often has an element of absurdity.

Yes, and it’s me. I have the silly side and the dreamy side. The title story from The Wilds has that dreamy, romantic quality to it. But my baboon novel has a range of tones. It’s Kafka-esque, I guess, because, for me, the dreamy, surreal stuff that I like often has an element of absurdity.

All of the stories in that collection might be dreamy. Or, at least, I was searching for some thread that connected them all, and it seems to be something about the spiritual infusing technology.

What about movies that just wrench you and twist you into an emotional pulp? To me, that would be technology working on you to help you reach a strange, heightened mental state.

You say movies, but do you think books do that?

Yes, books are a form of telepathy. What’s really weird is whenever I used to read Renaissance lit, one of my favorite things to research was the connection between print technology and angelology, because Aquinas had this theory that angels communicate via telepathy, that one angel just thinks a thought and it goes into the other angel’s head. And the closest thing to that is reading. I do feel that no technology so far has replaced that.

Until they do brain-to-brain telepathy.

Which they will—everybody will have a telepathy microchip enabling them to share thoughts. But there’ll be all kinds of viruses, don’t you think? We’ll connect with someone, disconnect, and go away with some existential virus.