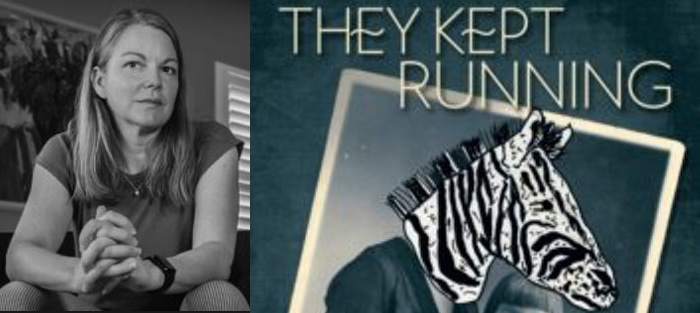

If memory serves, I first met Michelle Ross at the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference in 2017. That year, the event was held in Washington, DC, and Michelle and I were both at a get-together for past participants of Kathy Fish’s excellent online Fast Flash workshops. Michelle’s first story collection, There’s So Much They Haven’t Told You, had just been released by Moon City Press, and we chatted about her book’s journey from page to press.

Since then, I have been lucky to work with Michelle on two occasions. First, as the fiction editor of Atticus Review, Michelle accepted and published a small story of mine, and more recently, the journal I help run, Atlas and Alice, published a story of Michelle’s. In each of our encounters, I was taken with Michelle’s championing of fiction, as well as her incredible talent when it comes to pinpointing effective narrative structure. This asset is found on every page of her latest collection, They Kept Running, which won the 2021 Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction and was recently released by the University of North Texas Press. Consisting primarily of flash fiction, the collection is a true marvel that explores in small slices the lives of women and girls, and it shows how, when in the right hands, a few hundred words can truly shake a reader to their core.

In addition to her new collection and her debut, Michelle Ross is author of Shapeshifting, winner of the 2020 Stillhouse Press Short Story. Her fiction has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Colorado Review, Epiphany, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, TriQuarterly, Witness, and other venues. Her fiction has been selected for Flash Fiction America (forthcoming from W.W. Norton in 2023), Best Small Fictions 2021, Best Microfiction 2020 and 2021, and the Wigleaf Top 50 2019, among other anthologies. A native of Texas, she received her B.A. from Emory University and her M.F.A and M.A. from Indiana University. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, with her husband and son. She works in digital curriculum and assessment.

Michelle and I chatted over email about They Kept Running.

Interview:

Benjamin Woodard: They Kept Running is made up of 57 short stories, and I’m curious about the timespan of the collection. When was the first story published, and do you see shifts in your own style when looking back on earlier work?

Michelle Ross: The first of these stories to be published was “Three Ways to Eat Quince,” which appeared in the long defunct journal Word Riot in January 2016. The newest story is “Cake or Pie,” which appeared in Wigleaf in the fall of 2020. I love this question, but I also find it tough. I’ve been mulling this over myself in recent months as I reread these stories during the proofing process. I’m not sure that my style has changed all that much, but a few observations do come to mind.

One, I’m more comfortable now writing shorter. With few exceptions, most of my earlier flash tended toward the longer end of the range that is typically considered flash, somewhere between 600 and 1,000 words. For example, early on, I could not have written a story like “Fertilizer,” which is so tiny and spare. I think there are a few reasons for this. One is that the shorter a story is, the more vulnerable I feel as a writer. More exposed. There’s nowhere to hide. I think that writing short requires more confidence than writing long, or at least a different kind of confidence. Also, very short pieces are, of course, built of fewer materials—fewer sentences, fewer words, fewer metaphors, fewer craft elements altogether. So there’s more pressure on what is there on the page.

Two, and perhaps this goes hand in hand with writing shorter, I’ve also become more comfortable writing simpler, or seemingly simpler, stories. “Return” is one such example. It’s built of plainer language than more intricate stories, such as “The Funny Thing” or “Glow.” I’m not saying it’s a better story than the more intricate stories, only that writing such a story, for me anyway, requires more confidence. I think fancier language is another way that writers sometimes hide. Fancier language can mask a lack of a strong vision.

Three, I’ve become better at trusting my gut instincts even when I struggle to articulate why something is right. I just know I love this word or this sentence or this ending or whatever, and that’s enough. George Saunders’ talk about radical preference comes to mind.

To branch off this, I’ve always found that, when writing very short, I have to tap more into what I call “poet brain” (even though I would never consider myself a poet!), meaning I can’t waste any space. I have to hit the mark right away. Do you have any go-to methods for approaching micro fiction, for the confidence you mention? Also, how do you know when a story only needs to be, say, 400 words long compared to 1000 or 2000?

Microfiction feels more akin to poetry to me, too, though the difference being that there needs to be a narrative. What makes something a microfiction versus a longer flash fiction really boils down to the size of the narrative—or the number of beats required to tell that narrative in a satisfying way. Some stories can be satisfyingly delivered in a few sentences, while others have more components and require more buildup. It’s rare that I know what I’m setting out to do when I start writing. I usually begin with just a kernel of an idea, if even that. So it’s through the writing itself that I discover the story and, hence, how large or small it is.

Microfiction feels more akin to poetry to me, too, though the difference being that there needs to be a narrative. What makes something a microfiction versus a longer flash fiction really boils down to the size of the narrative—or the number of beats required to tell that narrative in a satisfying way. Some stories can be satisfyingly delivered in a few sentences, while others have more components and require more buildup. It’s rare that I know what I’m setting out to do when I start writing. I usually begin with just a kernel of an idea, if even that. So it’s through the writing itself that I discover the story and, hence, how large or small it is.

Outside of that, how I know what size a story needs to be again comes down to instinct, I think. Instinct is so fundamental to writing well, but it’s also mysterious and possibly impossible to teach? I think we develop it from reading a ton and writing a ton. To be clear, I don’t mean that I sit down to write and instinct swiftly leads me to where I need to go. I’m a huge reviser. As my writing buddy and collaborator, Kim Magowan, can attest, I’ll send her a story thinking it’s about done, and then despite her not having much in way of critiques, I will then go on to overhaul that story for three more months (or two more years)—all because instinct is now telling me the story isn’t quite right. Parts of the story are still nagging at me. My main writing “trick,” so to speak, is giving myself distance. I’d estimate that I work on over 95 percent of my stories for many months before submitting them. Sometimes a story may even be done for many months before I submit it because I’m just not certain yet. I put it aside for a while, then take it out and reread it; repeat, repeat. After doing that a few times and changing little to nothing, I’ll finally submit it.

This is a question that always fascinates me, so I’m going to indulge myself: Can you walk me a bit through the process of organizing a collection that consists of so many pieces?

I love, love, love the task of sequencing stories—moving stories around and comparing how they play off each other. Also, though, with 57 stories, I knew from the start that there was no such thing as the perfect order or the correct order. There are poor choices and better choices. But to make those better choices, I have some practices that I think have served me well. One, I write the title of each story onto its own notecard. Two, I print out every story in the collection. Note: when sequencing longer stories, I may print only the first and last pages, but for this collection, it made more sense to print the stories out in their entirety since they’re so short. Then I study the stories, noting key themes, images, etc. I jot these down on the notecards. In particular, I care most about the beginnings and endings. I want the ending of one story to speak somehow to the beginning of the next story. For example, I placed “Tea Kettles” and “Migration” next to each other because “Tea Kettles” ends on the image of a tea kettle shaped like a sheep, and “Migration” begins with a couple going on vacation to a sheep festival. I paired “Dendrochronology” and “Bargain” because “Dendrochronology” takes place in woods and is kind of dark and sinister, and the first paragraph of “Bargain” includes these sentences: “…there was something foreboding about him. I imagined he contained a dark forest inside his skin.”

I divided the book into three sections because I like having some room to rest between things, but also because I noticed that these stories, which are all about women and girls, spanned childhood, young adulthood, and more middle-aged adulthood, and that they could be fairly evenly divided up into those three phases of life. By dividing the stories in this way, the collection as a whole seemed to acquire a narrative arc it didn’t have when the stories were more randomly ordered.

The tricky thing about dividing the collection into three sections in this manner is that lines get blurry. Some stories I wrestled with more. They felt like they could go in either section I or II, others in either II or III. “Killer Tomatoes” is one example. The protagonist, who is thirteen, is sexualized by an adult man. His behavior toward her made the story feel like it could belong in section II. But, on the other hand, the girl is still very much a child. Just because the dude in the story doesn’t respect that she’s a child, and that he has no business sexualizing her, doesn’t make her a young adult. Therefore, I put the story in section I.

I’m glad you talked about the idea of key themes and images linking the end of one story with the beginning of the next in the book. I noticed this in spots and wondered if this was how the stories originally looked, or if you made any edits to create these links between narratives. With the idea of editing in mind, did any of the stories in the collection go through alterations between their original journal appearances and their inclusion in the collection?

I don’t think I edited any of the stories to make those connections. Weirdly (or not?), there were just a lot of them there already. Also, maybe I should add that the collection wasn’t these 57 stories from the start. That work I did considering themes and key images, etc. helped inform which stories would be included in the collection. Some other flashes I wrote in the same time period didn’t make the cut, not because I don’t think they’re good enough, but because they didn’t seem to belong with these pieces, they didn’t fit the larger arc of the book.

In terms of editing, mostly I just reread these stories looking for little things that nagged at me—sentences whose rhythm was a little off or words repeated in close succession. Then Carolyn Elerding at UNT Press did a fantastic job copyediting the book further.

One thing that always strikes me about your stories is your ability to pull in so many character traits and details in such tight narratives. Can you talk a bit about how you go about peppering these elements into a story? Also, would to touch on your use of pop culture in your work?

Sometimes I think of my flash as being spare on character details, but I guess that’s because I write different kinds of flashes. Some are more spare, some more dense. The denser stories tend to be the pieces I labor over more. Are they more intricate and dense because I work them more or do they require more work because of the nature of the stories? I’m not certain, to be honest. What I do know is that the more I labor over a story, the more material I write that doesn’t make it into the story, and nearly always, that extra writing benefits the story. I scavenge the discarded parts for the little details that are keepers. Or, alternatively, what I learn along the way helps me get to know the characters and so ultimately leads to more development and depth.

Ben, your question about my use of pop culture confused me for a few minutes. I was like, what pop culture references? How is that possible? I swear that idiom “live under a rock” was invented for me. I’m always out of the loop. Then I remembered the references in this book to Elvira, Hitchcock, Phineas Gage, Mike the Headless Chicken, fairy tales, and I thought, oh yeah, I guess my writing does touch on a lot of pop culture; it’s just that the references are all super dated.

When I do reference pop culture in my writing, usually those references are horror related or something bordering on horror. Horror films, at least classic horror films, operate kind of like fairy tales for me. They’ve shaped my sense of the world. They’re always there lurking in the recesses of my mind. I think horror as a genre, at least more progressive horror, is more truthful than many other genres.

Perhaps my thinking of these older references as pop culture shows my own age! I love how you reference horror and see the genre of horror films as kind of fairy tales. You blend the two together so well in a story like “Phainopepla,” and there’s a literal horror movie set in “The Scream Queen Is Bored.” Some of your stories present clear threats to their protagonists, and in others, threats feel just off screen in a way, waiting for the right moment. Does your own love of horror help you plot out these seen and unseen threats?

In the best horror films, the protagonists find that the humans in their orbit are every bit as threatening, if not more so, as whatever monster lurks. One of my favorite horror films is Night of the Living Dead, in which a bunch of strangers hole up in a house to escape zombies but then, inside the house, racial and other tensions alight and eventually become deadly. The zombies are dangerous, sure, but there’s nothing malicious about zombies. Humans, however, are another story. I love the more recent film 10 Cloverfield Lane—which gets categorized as science fiction/thriller, but which is also very much a horror film—for the moment when the protagonist escapes the man who has imprisoned her in his bunker only to find that Earth indeed is under siege by aliens, just like the man said. I love how this revelation doesn’t in the least lessen the horror inside the bunker. So what that the guy was telling the truth about the aliens? He’s still a monster. I’m still relieved she escaped him. I love how in films such as these, the horror is everywhere. This feels true to life. Not to say that life isn’t full of joy and wonder, too, that humans aren’t kind and generous; but, also, there are threats everywhere, and much of those threats come from humans. Both things are true at once. I guess this is kind of the world view I write from much of the time. I don’t know if horror films shaped me in this way or if life did.

I should emphasize too that there’s pleasure in these narratives. There’s pleasure in confronting what scares us, for one, but more importantly, there’s pleasure in the exposure of all the muck of human behavior that we’re not supposed to talk about, that we’re supposed to politely pretend isn’t all that big a deal. “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

I’m not sure I really answered your question here.

You did! I love these two films, as well. The whole “strangers trapped together” subgenre of horror can spin out some fascinating character profiles! Oh, I feel as if we could turn this into a horror movie conversation for hours, but our interview space is almost up, so let me pose one final question: When do you write? Do you have any particular routines that you stick with?

I could totally talk about horror films for hours, but yes, back to writing.

I’m mostly a morning writer. I’m usually up before five and squeeze in a few hours before the rest of the day begins. However, I cycle through a couple different writing states or phases. Some weeks, most weeks, I write in the morning and that’s pretty much it. I may not think consciously about stories I’m working on the rest of the day. My subconscious probably isn’t idle, but I’m able to easily set stories aside and focus on other things. Then there are the weeks in which I struggle to put a story out of my mind. I’m obsessive, intoxicated. It’s like new love, that phase. I might go for a run and write sentences in my head for miles and miles. I return to the house with copious notes. Or I might scribble notes at red lights as I run some errand or as I’m trying to fall asleep at night. I love that state. It’s exhilarating. But it’s also exhausting and all-consuming. It’s probably for the best that writing isn’t always like that.