“History buffs will thrill at the experience to explore towns last occupied generations ago, before eradification measures,” says an advertisement for the “Ghost Towns of the Old Republic” tour offered by Outer Limits Excursions, an adventure tour company that exists only in the world of Holly Goddard Jones’s new novel, The Salt Line (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2017), and on her website. The company offers clients the opportunity to “see Hickory, Marion, Black Mountain, and Asheville; learn about 21st century America and tour the beautifully preserved Basilica of Saint Lawrence.” Or one might try a hunting excursion: “Each traveler is allowed to bring back one large-game trophy kill through quarantine, through special arrangement with Atlantic Zone Fish and Wildlife.”

In The Salt Line, Goddard Jones creates a world in which wealthy travelers are willing to pay for the opportunity to see the world beyond a barrier that keeps them safe from a troublesome species of tick that causes Shreve’s disease, whose victims suffer a grisly sequence of nausea, numbness, and paralysis on their way to a death that will occur in less than a week. The travelers undergo three weeks of training to be sure they’re prepared to use a painful tick-removing device on themselves and their buddies when (not if, their tour guide emphasizes) they get bitten.

Pop star Jesse Haggard makes the trip because he wants a thrill. His girlfriend, Edie, the only one who understands how naïve Jesse really is, goes along to look out for him. Financial wunderkind Wes Feingold signs on because he’s having an identity crisis. And Marta Perrone, a housewife in her fifties, goes because her mobster husband, who wants to keep tabs on Wes, makes her. The group encounters not only the kinds of dangers expected on a tour like this, but additional ones concocted by a sinister group living out-of-zone, on the other side of the Salt Line.

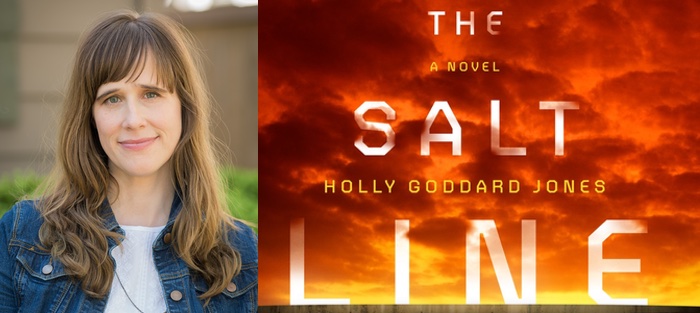

Goddard Jones has previously published a novel, The Next Time You See Me (Touchstone, 2013), and a short story collection, Girl Trouble (Harper Perennial, 2009). Readers familiar with her work know that she excels at developing multidimensional characters and suspenseful plots. In The Salt Line, she demonstrates her skills at worldbuilding as well, creating a literary page-turner rich with ideas. I talked with her about her new book over email.

Interview:

Danielle LaVaque-Manty: While your first novel and your short story collection were realistic and set in the here and now, The Salt Line is dystopian, set in the near future at a time when the borders of the U.S. have contracted and the country is divided into Zones. What led you to this change in genre? Or did it feel like a change to you?

Holly Goddard Jones: I didn’t make a big, clear decision to start writing in a different genre—if anything, I tricked myself into doing it. I had this idea about a burrowing tick and a crude, painful device used to extract it, and I thought it might be a fun horror story. I’d just read Scott Smith’s The Ruins, and I liked the idea of trying to write not just horror but small-scale, diffuse horror—horror in which the object of terror is a Little Bad, or a bunch of Little Bads, rather than a Big Bad. So I started the story thinking it would be a thirty-page one-off, and then I’d go back to literary short stories and maybe another novel project. But it kept getting longer and longer and more complex.

With the dystopian stuff, I was originally just trying to justify the book’s basic setup: tour group goes into the woods, encounters deadly, disease-carrying ticks, and stuff goes wrong. Why would these ticks exist? Why would people pay to put their lives at risk? You can see that I’m not a natural horror writer, because these were questions that didn’t necessarily need to be asked or answered for the sake of a good scare. But my impulse was to dig into those whys, and that’s how the social and political commentary began to emerge, and that’s when I knew I had a novel and not a short story on my hands.

Do you see a trend in contemporary fiction toward more speculative work? If so, do you have any theories about why that is happening?

Do you see a trend in contemporary fiction toward more speculative work? If so, do you have any theories about why that is happening?

It certainly seems more prevalent, and you see more literary writers working in the genre. The pat answer is probably that it’s because the world feels scary and uncertain, but I have a theory about that. Not to diminish all the bad things happening—and Trump’s election threw me into a bad depression, like it did a lot of people—but I think worrying about the worst that could happen is actually a sign of doing pretty well. Your belly is full, your checks are clearing, and so you’re contemplating the big, abstract sources of terror rather than the day-to-day grind of getting by. You’re waiting for the other shoe to drop.

What I’ve always liked about reading in the dystopian and post-apocalyptic genres—and this was the appeal of writing the book, too—was that there’s a way in which it conjures a lost past as much as it does a possible future. It gives you a chance to write about contemporary people, people like us, who are doing something other than checking Facebook on their smartphones. As much as The Salt Line says about technology and social media, when you break it down, it’s a story about people going into the woods and facing the scary thing in the dark.

With the range of potential disasters facing us today—nuclear war, famine, rising seas due to climate change—what made you conceive of ticks as a fundamental threat that could drive the U.S. to reconfigure its borders?

What a depressing question! Ha! Well, I can answer it in a couple of ways. The first is that new insect-borne diseases are one possible consequence of climate change, and you already see examples of how that’s true with Zika, Ebola, and increased cases of Lyme disease. But also, like I said, this was horror story before it became a dystopian story, and ticks are a tangible object of horror, one that taps into a natural revulsion that we already feel at the sight—or touch—of a regular old non-burrowing tick. Climate change is a broad, abstract category of problems; ticks are extremely specific.

You had to do some worldbuilding to write this book. For example, one of your characters, Wes, creates a new system of exchange that merges currency and social media. How did you decide what the future would include and what it wouldn’t?

I find this question hard to answer, actually, because I wrote big swaths of this book operating on instinct, and I had a lot of luck with the instincts later bearing fruit. I knew early on, for instance, that I wanted Wes to be a wunderkind, Mark Zuckerberg type, but initially, his work on Pocketz—the social banking system you mention—was just functioning as character trivia. I wanted him to be a tech mogul, and I wanted the tech to seem plausible in Wes’s reality. The more I wrote, though, the more thematically significant his work became, and then it started to take on heavier plot significance, too, which was a fortuitous and mostly accidental payoff.

One decision that I did consciously make was that the world of The Salt Line wouldn’t be, in most of the basic ways, that different from our world. I didn’t want the characters flying around in hovercraft or using smartphones-via-chip-in-the-brain. I’ll admit that’s probably because I’m not smart enough to guess what those technologies would look like and how they’d work, but I think it’s also just scarier if the dystopia feels really, really familiar.

It does feel familiar! One of my favorite moments is the visit, soon after your travelers cross over the Salt Line, to a Cracker Barrel Old Country Store on I-40, mysteriously still intact and functioning as a museum. The place is full of stuff “that would have been antique by the early twenty-first century.” Edie finds it more moving than a remembered visit to the Memorial to the Lost Republic and tries to imagine the people who would have purchased things there. That made me nostalgic for a store I’ve never even liked, thanks to the power of its specificity. Like ticks being easier to fear than climate change.

I have kind of a love-hate thing going with Cracker Barrel, and that shows in the book. I actually like the food, but the general store part feels like a shrine to most of the things I hate about America and the South. But, you know: it’s familiar, it’s home. When we eat at a Cracker Barrel, it’s almost always because we’re traveling I-40 west to visit family, so it’s kind of a way station back to my hometown—a tempering in anticipation of what’s to come.

Several of your characters—Marta, Edie, and Violet—have to choose between loyalty to individuals they are personally indebted to—people who saved them from physical hardship, support them financially, or both—and rescuing themselves and others. In each case, staying loyal is a safe but constraining choice, and it’s only the desire to help someone else that lets the character break free. Was this a theme you intended when you began writing, or did it emerge along the way?

I never thought about it in those terms, exactly, but I like what you’re saying a lot. I’m wondering, just because you mention three women, if it has something to do with gender—with the ways that women, specifically, find themselves indebted to, and dependent on, husbands or lovers or parents. One thing I do think I was consciously trying—and this was new for me—was to write about the transformative power of friendship. Marta is a middle-aged mob wife, and Wes is a twenty-something tech wiz with OCD, and it just doesn’t seem like a natural pairing, but the two of them are the book’s core relationship. It’s a relationship built on mutual admiration and affection, and there’s no troubling power imbalance, and that’s very, very different from what Marta has with her husband.

Marta’s husband, David Perrone, is a scary guy—a crime boss with political ambitions. I couldn’t help seeing reflections of our current president in him. Is that a coincidence, or did the 2016 election season influence his development?

David Perrone predated the election, but he certainly started to take on some Trumpian qualities as I did my last set of revisions, because all that work happened over 2016. The influence was natural, unfortunately, because David—even in his earliest iteration—was a character driven by a desire to be seen, admired, and kowtowed to. He didn’t have an ideology, and he saw his wife and children as an extension of himself, and his public worth, rather than as unique humans deserving of empathy and compassion. Watching the election play out, and all this talk of wall-building—and The Salt Line has a big barrier wall, too—made me start to consider David as not just a crime boss but a budding political force.

The boundary represented by that big barrier wall in The Salt Line has a lot in common with our current border, in terms of who is protected from what, but also in terms of the economics of drug production and distribution. Much in the story turns on the role of a drug called “salt” and who will control the outcome of a certain pharmaceutical discovery related to it. You do a fantastic job of demonstrating how new knowledge could transform an economic and political system—or be prevented from doing so.

Thanks—that means a lot. Most of the research I did for this book wasn’t about ticks and disease but about drug trafficking between Mexico and the U.S. It’s fascinating stuff. One of the most fascinating things in this one book I read, El Narco, was about the culture around drug production, and how even religion gets mixed up with the drug economy. I originally had a religious tie-in to Salt—a kind of fundamentalist border sect—but I cut it so I could give better due to the story’s other threads.

I don’t want to give away anything about the ending, so let me just say that it seems a confrontation may still lie ahead for two of this novel’s more ruthless characters. Can I ask if there’s any chance that your next book will tell us what happens when they meet?

The next book? No. But my next book will be connected to The Salt Line—it’s set in the same fictional world, but on a different timeline and focusing on a mostly new set of characters. I have a rough idea for a third book that will connect the first two, should these do well enough to suggest there would be an audience for it. If that third book happens, yes: those characters’ paths will cross again.