Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

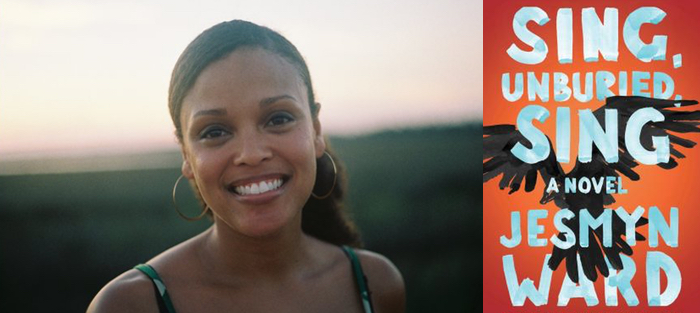

This week we’ve returned to Nico Berry’s interview with Jesmyn Ward, which was originally published on August 19 of 2009. The two discuss Ward’s debut novel, Where the Line Bleeds, representation, and her then-in-progress project, which would become the National Book Award winning novel Salvage the Bones. Ward’s newest novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, was released by Simon & Schuster this week.

Jesmyn Ward grew up in DeLisle, Mississippi. Her first novel, Where the Line Bleeds (Agate, 2008), is about twin brothers navigating life after high school in a small Gulf Coast town.

Like many of the authors she admires, Ward gracefully captures the intricate dynamics among families in the rural American South, as well as the region’s beauty and its particular trials. When asked about her influences, she mentions the novel Cane, written by Jean Toomer during the Harlem Renaissance. “He wrote this novel about the South and got it right,” she said. “He captured something so amazing and beautiful, but also nebulous—this quality the South has that fascinates me and makes me want to write about it.”

Where the Line Bleeds is an Essence Book Club Selection, a 2009 Honor Award recipient from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, and a nominee for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award (winner to be announced in November 2009). The manuscript version of the novel also received the Hopwood prize at the University of Michigan. Ward has had essays and fiction published in Oxford American, A Public Space, and Bomb magazines. She holds a B.A. in English and M.A. in communication from Stanford University, and an MFA from the University of Michigan. She is currently entering her second year as a Stegner Fellow at Stanford.

Nico Berry spoke to her by phone as she soaked up the summer heat back home in DeLisle, Mississippi.

Interview

Nico Berry: I was going to start with the two epigraphs that you have at the beginning of your novel—one from the Bible1 and one from [the rapper] Pastor Troy2. Which had a bigger influence on your life—hip-hop or the Bible? [Editor’s note: see “Notes” section below to read these epigraphs in full.]

Nico Berry: I was going to start with the two epigraphs that you have at the beginning of your novel—one from the Bible1 and one from [the rapper] Pastor Troy2. Which had a bigger influence on your life—hip-hop or the Bible? [Editor’s note: see “Notes” section below to read these epigraphs in full.]

Jesmyn Ward: When I was in high school, it was God. I went to a private Episcopalian high school, and I used to go on retreats, and I was really into it for a while. But my senior year, I was surrounded by people who were really close-minded about the Bible and Christianity. It turned me off and I slowly stopped believing.

Hip-hop didn’t really blow up for us in the South until after NWA, and then we started getting some people from the south like 8-Ball and MJG and UGK, reinterpreting hip hop in a southern way. It was so good having someone talk about the realities of where we were from, and doing it in a way that lyrically, and sonically resonated with us. That’s when hip-hop became the big thing here. I think both hip-hop and the Bible have been really influential to me at different times in my life.

It seems interesting you used these two counterpoints to start the book.

Really I started with the Pastor Troy. I used to listen to the song over and over again when I was germinating the seed of the novel. I was doing a lot of driving at the time, from Michigan to Mississippi, sixteen hours each way. I would play that song on repeat. I decided to use this passage for a quote, and then, because of what it talks about, I wanted to pair it with something. The Pastor Troy came first—and then the quote from the Bible.

Why did you feel like you had to pair it with something?

Because nobody respects southern rappers—they’re seen as just the latest trend that needs to end as soon as possible—or least that’s what it feels like. No one seems to respect southern rappers lyrically, so I wanted to pair Pastor Troy with that quote from the Bible to add emphasis to the verse, and add a certain legitimacy to it—to show that he’s talking about real issues that should be taken seriously.

Do you worry that that attitude towards southern rappers crosses over to how people treat southern writers too?

Yeah, maybe. Before the book came out, I read an interview somewhere that said how southern writers are pushed really strongly in the region, but not really outside the region. It’s hard for a southern writer to break through outside the region, which they thought was really odd considering that the south has this great history of amazing writers. Sometimes I wonder if this applies to black writers also—if there’s not space for anyone besides the heavy-weights and big exceptions. There’s a lot of room for hood writers, but it seems like it’s hard to get into that other space—the one for black literary writers.

What about being a woman writer? Do you think that makes it harder too?

Sometimes I wonder if because you’re a woman someone’s less likely to think you have great literary merit. If you look at the hot young writers a lot of them are men—but I don’t know. I’ve thought more about how being black affects where my work is read—not as much about being a woman.

It’s almost as if you’ve got three strikes against you as a writer—black, southern, and woman. Do you think that affects the way you write?

I think it makes me more motivated to write past all of that and create great literature. Maybe that’s how it affects me.

I understand that some of the characters in your new novel you’re working on right now have carried over from your first novel, Where the Line Bleeds.

In the first novel there’s a scene in Javon’s house with the twins. There’s a whole bunch of people gathered there, including a lot of peripheral characters—Christophe, who is watching the guys playing dice, Skeetah and Marquise, and I think the character Big Henry is there too. These are some of the main characters in the second novel [Salvage the Bones].

In the first novel there’s a scene in Javon’s house with the twins. There’s a whole bunch of people gathered there, including a lot of peripheral characters—Christophe, who is watching the guys playing dice, Skeetah and Marquise, and I think the character Big Henry is there too. These are some of the main characters in the second novel [Salvage the Bones].

There was something about Skeetah’s character that struck me. I knew that there was a pit bull that he was obsessed with. I wrote a short story about him, and then I kept coming back to him—these situations he was in with Big Henry. Skeetah’s character was always there in the back of my head, and I wanted to live in that world he was living, explore that world, get to know who he was. I also had the idea of writing from a girl’s perspective, this girl who lives in a world full of men. Basically I took both those ideas and smashed them together, and made Esch, who’s the girl and the narrator, and Skeetah her brother. I created this family for her.

Was the Pastor Troy verse the seed for your first novel? Or was there a character who was the seed, the same way Skeetah was for the second?

The Pastor Troy verse was definitely one of the seeds for the first novel. I knew I wanted to create a fictional DeLisle, the town where I’m from, a fictional southern small town. So I knew the setting. I just didn’t know what it was going to be about. I did a lot of driving, and I listened to Pastor Troy a lot.

How much of Bois Savage [the setting for Where the Line Bleeds] is taken directly from DeLisle? Are any of the characters based on real people?

They’re all imaginative amalgamations. I’m calling the place Bois Savage, but it’s an idealized version of home. The Oaks in the book is modeled on the Pecan Grove in DeLisle, which is also a baseball park with a Blues club right next to it. There’s a park where a lot of stuff happens in both novels—and that’s modeled on the county park we have here—as are all the swimming holes, and swimming at the river. But then there’s a lot of things here that I haven’t gotten into in my fiction, partly because I’m so homesick for that older version of home. That DeLisle I wrote about is different now because of the casinos, and Katrina also irrevocably changed it. Bois Savage in the book is still really rural and there’s not a big police presence, which is how DeLisle used to be. Now there’s definitely a large police presence in DeLisle. I know that I should write about the way things have changed, but I can’t tackle it yet. I want to stay in that world for as long as possible.

Has anyone who lives there read and commented on the similarities?

I have this huge extended family, and I got really good press down here. A lot of people around here have read it. People have said to me, “I read it and I couldn’t put it down because I keep recognizing things.” They’re not talking about the characters, but the actual place itself. So far all the feedback I’ve gotten from everybody at home is that they love it. That was one thing that I was really nervous about. I wanted to get it right.

I’ve had people say to me, “You really representing.” I think it feels new to them to see this place represented in another art form. There’s a poet, her name is Natasha Trethewey. She’s African-American and her family is from around here and she’s written poetry about the area. But there haven’t been any African-American fiction writers coming from this area. I think people think it’s cool to see this place reflected back at them in fiction.

I’ve had people say to me, “You really representing.” I think it feels new to them to see this place represented in another art form. There’s a poet, her name is Natasha Trethewey. She’s African-American and her family is from around here and she’s written poetry about the area. But there haven’t been any African-American fiction writers coming from this area. I think people think it’s cool to see this place reflected back at them in fiction.

When you started writing did you picture yourself as someone who would really represent for your area?

It wasn’t until the very end of my senior year, when I was applying for college, that I wrote about DeLisle. That’s when I realized that this place is my inspiration.

Do you think you could have ever written about it if you hadn’t left?

I don’t know—probably not. Throughout high school I was thinking, I just want to get away. But when I realized I would be leaving, I looked back and saw the place differently. Both the good and the bad.

It’s interesting because in the novel neither of the brothers wants to leave. It doesn’t seem to even really be an option for them.

I wanted to make it like that. For a lot of people here that’s how it is. Leaving’s not an option.

But it’s not a sad thing. The brothers are where they want to be. They’re happy.

Yeah, I wanted it to be like that. Sometimes I used to wish that I had turned out like that.

You wish you were down at the docks.

Working offshore, making like 60,000 dollars slanging fried eggs to people.

Notes: Epigraphs from Where the Line Bleeds

1.

“And Isaac entreated the Lord for his wife, because she was barren; and the

Lord was entreated of him, and Rebekah his wife conceived. And the children

struggled together within her; and she said, If it be so, why am I thus? And

she went to inquire of the Lord. And the Lord said unto her…two manner of

people shall be separated from thy bowels….”

– Genesis 25

2.

“Why Jesus equipped with angels and devils equipped with Pac?

For God so loved the world that he bless the thug with rock.

Won’t stop until they feel me.

Protect me devil, I think the Lord is trying to kill me.”

– Pastor Troy, “Vice Versa”

Further Resources

- Hear Jesmyn Ward read an excerpt from Where the Line Bleeds, recorded at WWNO in New Orleans, LA, for BOMB Magazine’s Fiction For Driving series:

- Read Jesmyn Ward’s story “Cattle Haul,” published in Issue 5 of A Public Space.

- Ward has also written about her experience during Hurricane Katrina for The Oxford American in an exquisite essay entitled “We Don’t Swim in our Cemeteries,” which was published in issue number 62, the Katrina Anniversary Issue. More recently, she’s written a short piece for OA entitled “Obama I: Blood Dread and Hope,” in issue number 64.