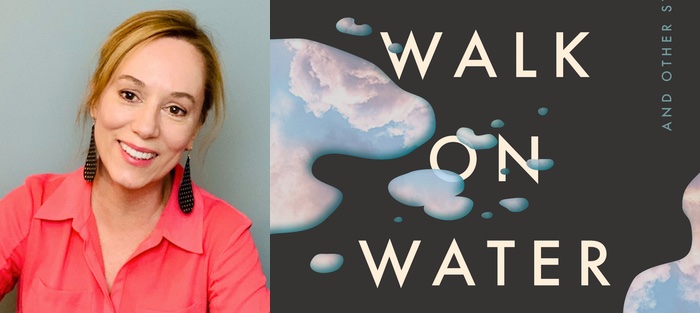

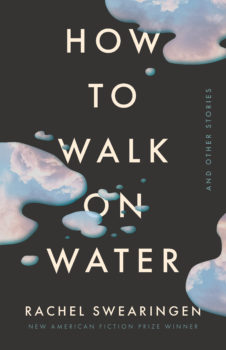

Rachel Swearingen’s debut collection, How to Walk on Water (New American Press), brings together stories she’s published over a period of years in such venerable outlets as Agni, Missouri Review, Kenyon Review, and American Short Fiction. The book won the New American Fiction Prize, and with good reason: these are inquisitive stories that probe the lives of women who inhabit liminal, eccentric worlds they’ve carefully constructed for themselves—worlds they’d do anything to escape, often as not, which is where things get interesting. The author keeps a close eye on her fraught protagonists as they experiment with new personas and pursue odd obsessions, many of them delightfully strange. The combination of Rachel’s low-key, elegant prose and her characters’ odd high-wire acts makes for a damn good read.

Rachel Swearingen is the recipient of the 2015 Missouri Review Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize in Fiction, a 2012 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and the 2011 Mississippi Review Prize in Fiction. In 2019, she was named one of 30 Writers to Watch by the Guild Literary Complex. She holds a BA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a PhD from Western Michigan University. She teaches at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago.

Interview:

Edward Hamlin: I want to ask you first about haunted places. The opening and closing stories each have one—a nightclub in one case, the apartment of a dead woman in the other. So I’m curious if you believe in ghosts.

Rachel Swearingen: I believe in the feeling of being haunted. I believe that places can contain impressions from people, histories, and cultures that came before, and that we can sense these things. We’re often trying to figure out where we fit in all of that. We know other people have come and gone, and I think a lot of us are contending with our own sense of mortality, that slippage of time.

My dad was an antique collector. As a child he would go out and dig in the woods in places where there used to be landfills; he’d find old baseball cards in cigar boxes and all sorts of strange objects. He did this throughout his life, became what they now call a picker. He’d get invited to strangers’ homes, and would talk to people about all sorts of subjects. He loved history. Sometimes, after a death, the next generation would throw out all these Victorian photographs, journals, and mysterious things. Once he found a handwritten manuscript that belonged to a classical musician from Minnesota, and we were able to get it into a museum. All these objects were constantly passing through. And yet my dad was a pretty haunted guy trying to figure out his own past. I think that searching filtered into me.

We also moved from house to house when I was a kid. My parents lived in at least twenty-five different apartments and houses during their marriage; they were constantly moving and buying another house and fixing it up.

Was that a conscious thing? Buy a house, improve it, flip it, make money?

Was that a conscious thing? Buy a house, improve it, flip it, make money?

[Laughs] No! It was restlessness. And they had a growing family and hoped to improve things, get better jobs. Both my parents worked in hospitals. My mother was a nurse. My dad was trained as a medic and worked in ERs. When he was laid off in his fifties, my parents bought this dilapidated old house in northern Wisconsin to fix it up, and he became a full-time antiques guy and became very good at it. For the last twenty years of his life he really bloomed. He’d rescue entire truckloads of books.

Talk about following your bliss. On the theme of antiques, you have an image, mirrored in two of the stories, of a woman who nibbles on antique postcards.

There’s a line in a poem by Mary Ruefle [“Like a Daffodil”] that says: “I had the urge to eat postcards of famous paintings.” Beth Marzoni, a poet friend, challenged me to write a story with it, and I wound up writing three stories, two of which made it into the collection.

It’s such a striking thing, this dysfunctional but also metaphorical image. I’m not surprised you kept coming back to it. Staying with the arts, there are two interlocking themes in your stories that really intrigued me. One is the idea of visual illusion, which several of your characters dally in. Then there’s theater, the idea of performance—your characters Felina and Vera, for example, who both do these role-playing, magical things, reenacting film noir and crime scenes and so on. Stuff that feels creative but a little psychologically dysfunctional…not that those are necessarily opposed concepts. What’s your relationship with theater?

I love theater, and I love people who are generous storytellers. I’m fascinated by the duality of the generosity of performance and the falseness of it. I’m interested in where the lines are between reality and fantasy and between generosity and self-absorption. Writing about visual art, and movies and so on, just brings out these themes.

Which is interesting for a writer who spends a lot of her time at a desk, alone. It’s so contrary to our wiring as writers to get out there and perform, though I’m sure we both know writers who are flamboyant and have that capability. I suspect that doesn’t include anybody on this call.

Well, I don’t know about you, but when you get some of us together and get a couple glasses of wine in us that all changes.

Yeah. I may have a recent example of that which we can talk about when we’re not recording.

In your book, the characters who have this performative tendency are generally women, many of whom are a little bit broken. Do you think the urge to perform is somehow a compensatory mechanism for them, and is it different for men?

That’s a really good question. I grapple with the tropes of the virgin and the whore, the femme fatale, the girl next door—all stereotypes that break down quickly. Yet culturally, for women from my generation and older at least, there are so many messages about how you perform publicly and how you perform privately. I think it’s different for men, though that’s being pretty binary. Most men seem more comfortable with performance, at least in the work world; everyone just accepts that it has to be done and it’s not a big deal. For women, it’s more complicated.

It seems to me that the performance roles men have are so calcified and predictable, whereas the women in your stories are much more creative. They’re inventing personas for themselves that are really singular. They don’t fall into any easy categories—they’re making it up from whole cloth. I’m not sure it helps them emotionally in every case, but they are unique.

I think it’s difficult for many of us to be more imaginative in our lives. In American culture, there’s this puritanical sense that we’re not supposed to play and imagine, though there may be spaces where you’re allowed to do so under certain constraints. I’m close to the men in my stories too, and often they embody difficulties I have in trying to live a more free and authentic life. Writing in another gender helps me to get distance, and that distance allows me to get at some uncomfortable material.

For sure.

There’s a class element, too. Working class families tend to play pranks, especially the boys. At least where I come from. I remember wanting to be one of guys and playing pranks on my siblings, but they always backfired. Girls were supposed to be well-behaved, but I would spend hours concocting ways to really get them.

There are some very successful pranks in this book. A lot of laugh-out-loud moments, too. You have a character who has to suppress the urge to confess to strangers that she’s wearing a dead woman’s underwear. Such a good characterization but also just so funny.

Thank you.

I was intrigued by the women in the stories who are stuck in their lives in one way or another, but feel safest in confined spaces. There’s a claustrophobia element. But these are usually chosen spaces, spaces where the women feel most comfortable. I’m curious if I’m reading that right, and also what your writing spaces were like.

Part of it might be a fear of mine, because I can’t stand being inside or sitting down for too long, so maybe I was trying to write through that. In some of the stories there is a desire for liberation and breaking out of constraints. Those performative aspects we talked about are staged in domestic spaces. I’m definitely ready to write some liberation stories.

I’d like to talk about your use of negative space. You leave a lot of space for the reader to fill in. You’re good at subtraction, which I’m bad at. It’s something I totally admire.

I wouldn’t say that. I’d say you’re great at it, and at writing beautiful, long sentences. I think every story requires a different sensibility.

I always write maximally and have to start unplugging. But in your stories, you sometimes suggest backstory but don’t go there, you leave it elliptical, which is great. You leave it to us to participate as co-creators. As a fellow writer, I couldn’t help making up my own backstory, wondering how I would have developed it and so on. Do you have the temptation to flesh out backstory? Do you go there and then take it out? Do you know things about the characters that we don’t?

In a lot of the stories I was thinking about how little we really know about people. When my character Edith showed up looking like a praying mantis, I thought, Oh, no, I really don’t know what’s going on here. I wanted the reader to have that curiosity too. I do tend to cut backstory as I revise, however. I find that it often bogs down my stories.

Back to your writing spaces.

Almost all have been small spaces. I wrote many of these stories in Kalamazoo, where I had a little office upstairs. I wrote in coffee shops, as well. And several stories were drafted here in Chicago. My office now is tucked away in the lower level of our apartment. I wrote the Edith story in a borrowed cabin in Traverse City. It was after the summer season. My dog was constantly barking and growling and I was by myself, so I didn’t feel safe, and that feeling entered into the story. I do tend to write inside though. I think my brain might be a little claustrophobic. You sit at a desk, don’t you?

At my desk or at a table. I just realized something about this, actually. The project I’m working on now has a current-time story set in 2019 Chicago which braids together with a story a hundred years earlier, end of World War I, in Boston. It just hit me today that without any conscious thought I’ve been writing the Chicago sections in my usual office upstairs, where I do most of my writing, and then I’ve been writing the Boston sections down in the basement.

You didn’t plan it?

I didn’t plan it at all. The change in space helps me change frame.

That makes perfect sense.

I also wanted to ask you about writing the Midwest. What’s that like?

Writing about the Midwest was so hard for me for so long. I tried to hide the fact that I was a Midwesterner.

That’s interesting, isn’t it, that urge. I’ve lived that lie.

I only started coming out about a decade ago, after I came back and knew I was going to stay. In so much literature the Midwest is a place that’s kind of stuck in time, or a place you stop through on your way to one of the coasts. It’s the place you’re from. But that’s not true, of course, and there are so many fantastic Midwestern authors who celebrate the Midwest.

There’s the Midwest and then there’s Chicago, right? Detroiters might say Detroit.

Have you ever sat in on a panel about Midwestern literature? I don’t think there’s even an agreement about where the Midwest begins and ends, let alone what it means to be a Midwestern writer. Chicago has an amazing literary tradition. I’m not from Chicago originally, and I haven’t absorbed it enough to be a Chicago writer yet. Do you still think of yourself as a Midwestern writer?

I don’t know. I have a second story collection in manuscript and a lot of the stories have a Chicago connection, but then there are Colorado stories, and European stories. Two of the anchor stories are about a couple from Chicago who decide, through happenstance, to move to Colorado and become sheep ranchers; the stories follow the arc of that misadventure.

It is interesting how often readers want authors to resemble their stories, to locate them in the settings. You’re supposed to have lived the experience.

So, I’m curious what COVID-19 has done to your writing routine. Are you more productive? Less productive?

I don’t know that I’m more productive. My writing routine is pretty solid right now. But the pandemic is making me think about what I want to write and why, and what I want to give to the reader. I’ve had a few readers express that some of my work is just too heavy for them. So I’ve been questioning that—not only the themes and subjects, but what I want to give. Before I would just plow ahead—whatever was right there, I would start working on it. I’m feeling a little more deliberate these days. How about you?

Same. I think the phrase that came to mind while you were talking was emotional capacity. I think it applies to the writer and the reader. Right now I feel like my emotional capacity as both a writer and a person is diminished; I can’t take on much more darkness. I recently overhauled a novel with some difficult themes and it was an emotional struggle sometimes to drag myself to the keyboard. At some point I realized it wasn’t the novel, it was me, reacting to the state of the world.

Sometimes you have to decompress. Lawrence Durrell highly recommended building dry-stacked stone walls as a way of getting your head out of writing.

I love the idea of stacking stones. We writers forget our bodies too often. It’s too easy to become disembodied.

Which brings us back to where we started: you and your haunted spaces.

Yes. Funny how so much in life is circular. What is that saying? There are no endings, only new beginnings?