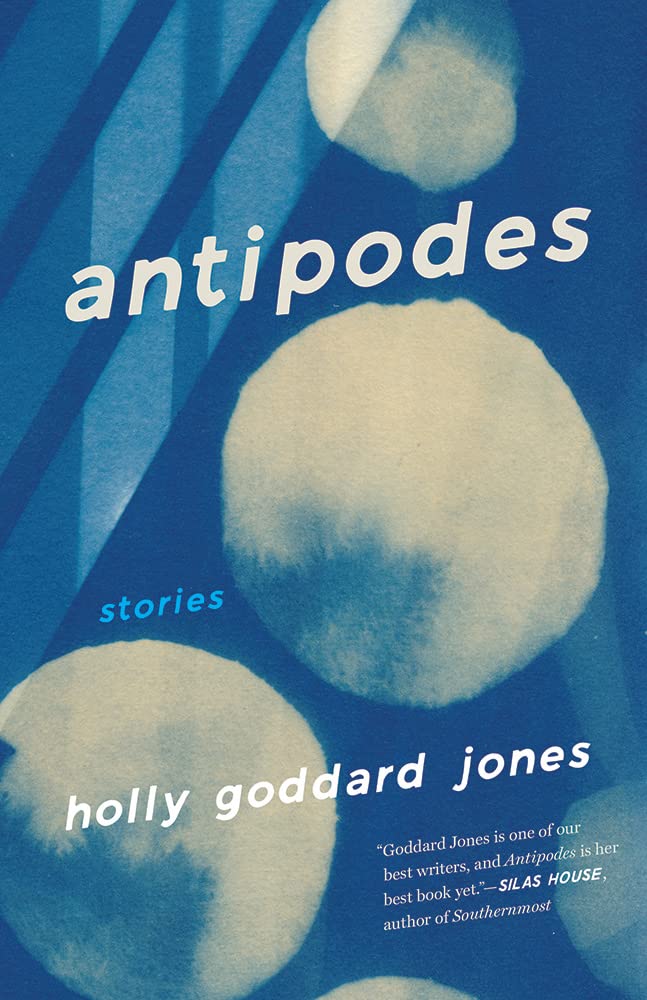

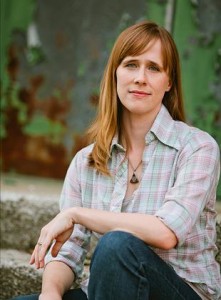

Holly Goddard Jones has always been an early starter. She got married at nineteen—see her blog post about this in Salon—and published her first chapbook of stories right after graduating from college. She grew up in a small town in Kentucky, where her father has worked in a factory for more than fifty years. I met her when we were graduate students in the MFA program at Ohio State. She was in her early twenties, and Columbus was as far north as she had ever been. Two things I soon learned about her were that she had never traveled on an airplane and she missed sweet tea. Since then, she has flown to Rome to promote the Italian translation of her short story collection, Girl Trouble, and to London and New York for fun. Her stories have appeared in Best American Mystery Stories, New Stories from the South, The Southern Review, Epoch, The Gettysburg Review, The Kenyon Review, Shenandoah, The Hudson Review, and Tin House, among others. And sweet tea has become available everywhere.

Holly Goddard Jones has always been an early starter. She got married at nineteen—see her blog post about this in Salon—and published her first chapbook of stories right after graduating from college. She grew up in a small town in Kentucky, where her father has worked in a factory for more than fifty years. I met her when we were graduate students in the MFA program at Ohio State. She was in her early twenties, and Columbus was as far north as she had ever been. Two things I soon learned about her were that she had never traveled on an airplane and she missed sweet tea. Since then, she has flown to Rome to promote the Italian translation of her short story collection, Girl Trouble, and to London and New York for fun. Her stories have appeared in Best American Mystery Stories, New Stories from the South, The Southern Review, Epoch, The Gettysburg Review, The Kenyon Review, Shenandoah, The Hudson Review, and Tin House, among others. And sweet tea has become available everywhere.

Holly is currently an assistant professor in the MFA program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and has taught in the summer master’s degree program at the Sewanee School of Letters for the past three years. Her debut novel, The Next Time You See Me, is being published by Touchstone this month. I conducted this interview with her over a series of email exchanges near the end of November 2012.

Interview:

Danielle LaVaque-Manty: You imagine your way into a lot of dark places in your fiction, with two of the stories in Girl Trouble focusing on a murder (one from the victim’s mother’s point of view, and the other from the point of view of one of the killers) and with your novel, The Next Time You See Me, built around the death of one of your characters. What draws you there?

Holly Goddard Jones: Maybe it’s just a macabre sensibility—it certainly doesn’t rise from some childhood trauma. But I do remember, from a very young age, being interested in the dark stuff. As an elementary and middle-schooler, that meant reading YA horror, like R.L. Stine. By seventh grade I was reading Stephen King.

As a writer, it’s a fascination with high stakes. The life-and-death stuff comes more easily to me than the subtle domestic stuff, or wryly playful stuff, which I’ve been trying to do in my most recent short fiction.

Many writers work the other way around, I think—having to work their way toward the dark. What makes you want to try the “subtle domestic and wryly playful” stuff now?

Well, I think I needed to mature and get more practice before I could do it the way I wanted to do it—do it justice. When I was an undergraduate mimicking Raymond Carver and Lorrie Moore and folks like that, I didn’t really understand enough about being a grown-up to get why a story about, say, a mother and daughter taking a trip together could work as well as Moore’s “Which Is More Than I Can Say About Some People” does. I saw the wit, and I saw the novelty of the device driving the story, but I missed the wisdom. I’m not saying I’m wise now, but I understand more than I did at twenty-one, and I can more fully appreciate the darkness and comedy of the everyday. It touches me now in a way that only tragedy used to touch me.

One thing that struck me about The Next Time You See Me is the number of cruelties the characters inflict on one another—some reflexive, like when Christopher calls Emily a “creep,” some more deliberate, like in the cafeteria scene where the kids pelt her with food, and some unintentional (“unthinking,” as you say in the book), like when Sonny brings another woman to the bar where he usually hooks up with Ronnie. Was this range of cruelty something you deliberately set out to explore?

It was. People were talking a lot about bullying when I was working on the draft. That’s sort of a buzzword now—every act of unkindness against another person, no matter the age of the people involved or the power dynamic, is bullying. So I was thinking about bullying, how that could play out among children, sure, but also adults, like the way this young guy at the factory, Sam, bullies Wyatt, whom he perceives as a square old man. But I didn’t want it to be a good-and-evil thing, a “the powerful always prey on the weak” thing. In the original draft, there’s a scene in which Ronnie thinks very consciously about how she’s going to intentionally hurt a person, and she feels guilty about it, but she also can’t help herself. It’s complex, and I liked that part a lot. But, because of some bigger structural changes, I had to shift that moment out of her perspective, and so I lost it, and you can see her actions but not the motives behind them.

I hope, though, that Ronnie still embodies for the reader some of the qualities of aggressor as well as victim. I think one of the things I was trying to say about cruelty is that we’re all capable of it, and sometimes where you fall—whether you’re aggressor or victim, and how far it goes—is circumstantial, or just bad luck.

You tend to write long short stories, and I remember you saying once that you were working on something you had hoped would be a novel but it turned into a short story instead. What let The Next Time You See Me become a novel rather than a story?

That’s interesting—I don’t remember the novel that turned into a short story, but I’ve been told more than a couple of times, “It seems like you could have just made that story into a novel.” There was a time, when I was desperate to produce a novel (and knew that the fate of my story collection may well depend on my ability to do so), when I wished it was that easy. That I could just take one of my stories, pad it, expand the timeline a little, and boom: two-book contract. But it never worked out that way for me.

Why was this new book different? An obvious reason is that I decided to tell the story through multiple characters’ perspectives. My short stories tend to focus on a single character’s point of view. And as soon as you give the reader access to multiple characters, you put yourself in the position of telling multiple stories. So this became a novel not just about Ronnie’s disappearance but about Susanna’s marriage, Tony’s ambitions, Wyatt’s regrets, Emily’s suffering. When I got to know each of the characters better, and I saw what was going on with them outside of their roles directly related to Ronnie’s disappearance, I began making causal connections, so that there’s a complicated (and for me, satisfying) architecture to the book, in which the storylines all start to influence one another. All of this let me, in the last third or so of the book, introduce a new major plot development in a way that felt earned and not like a desperate eleventh-hour move to bring the story to a close. At least, I hope that’s how it feels for the reader.

The fictional town of Roma, Kentucky, where both this novel and the stories in Girl Trouble are set is much like your own hometown, right? Have friends and family from home read your work, and if so, how have they responded?

A number of people back home—family, old friends, strangers, I guess—have read Girl Trouble. I’ve gotten a range of responses to it, mostly supportive, some a little frustrating. I’ve shared this anecdote before somewhere, but my aunt felt compelled to tell me, in front of the casket at my uncle’s funeral, how she didn’t like it. “I didn’t like it,” plain as that. She’s very religious, and the book seemed obscene to her. (I should add that I love this aunt, and I wasn’t too hurt. She was also the aunt who told me how fat I was when I was a little girl. It’s just her way.) But another aunt, on the other side of the family, sent me an email telling me how good she thought it was—she was very specific and thoughtful about why—and that surprised and moved me. We hadn’t been really close, and I don’t think we’d have shared an exchange like that if not for the book.

There are people who want to take things literally, see a little detail and think they’re reading a larger truth into it, and that causes me the most anxiety. Because I pluck details from real life all the time, and mostly don’t even register consciously that I’m doing it. If the detail leads you to read as truth the big bulk of fiction I’ve constructed around it, yikes.

No one at home has read the new novel yet. I have to admit that I’m nervous about it.

You’ve mentioned pursuing new directions in your writing. Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

I’m just trying to push myself and do new things, jolt myself out of any notions I have about what “my thing” is. That’s hard in a lot of different ways. It’s hard because I think it’s easy to train yourself into excelling at a certain kind of style, or telling a certain kind of story—it can feel like, well, it’s not in my wheelhouse to write a satirical story about a writer. But it’s also hard because you build an audience, however small, and showing them this new stuff can be jarring. I wrote a new story about a gay interior designer—it takes place over the course of a night, when he’s hosting a party in his home, and the climactic action is very subtle, just an overheard conversation—and my editor read it, and I could tell it threw her, maybe even worried her, in the way it might throw my colleagues if I showed up to work wearing leopard print boots and bright red lipstick.

So I’ve started a new novel, and it’s really, really different. It’s not a quiet domestic story, but it’s not Girl Trouble or The Next Time You See Me, either. I’ve never been so insecure about the basic premise of a project, especially one that I’ve so enjoyed writing, and so it’s been a fraught few writing months.

Further Links and Resources:

- Read Holly’s short story, “Who Cooks for You,” at Five Chapters.

- Check out Holly’s blog.

- Follow Holly on Twitter.