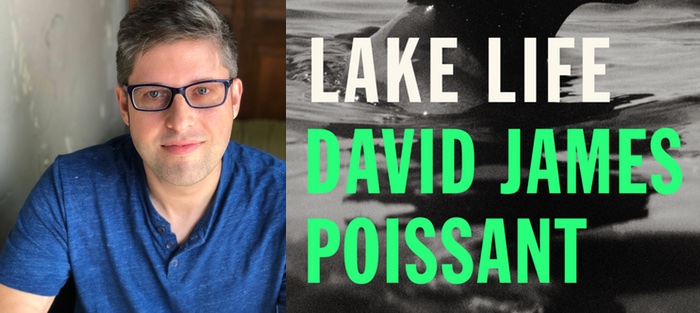

David James Poissant doesn’t have to prove a damn thing to anyone. He’s already a short story virtuoso, with fiction of his appearing in places like The Atlantic, The Chicago Tribune, One Story, Playboy, Ploughshares, and the like, and his debut collection, The Heaven of Animals (Simon & Schuster, 2015) was released to wide acclaim. It’s been translated into several languages and was up for multiple prizes, including GLCA New Writers Award for Fiction, which he won. For so many short story authors, though, there’s always that pressure in the industry to follow up with a ‘proper’ novel before the author can prove their worth.

But with the forthcoming release of Lake Life (Simon & Schuster), Poissant rises so far above expectations that it seems like he’s been writing novels his entire existence. The form and execution of the work here are masterful, and the characters and settings are brilliantly painted, starting with Richard and Lisa Starling, who’ve decided to sell their small summer house on Lake Christopher to developers. Over three days of their last trip to the home—including the Starlings’ sons, Richard (and his wife, Diane) and Thad (with his partner, Jake)—a tragedy involving the death of a small boy on the water hits the family unexpectedly, and the Starlings’ own tragedies and secrets are put up to the light as a result.

Poissant and I had the chance to talk over the phone recently about politics, class disparities, and, inevitably, the pure awesomeness of the X-Men.

Interview:

Barrett Bowlin: What was the genesis of Lake Life? What scenes or images started the work up for you?

David James Poissant: The answer to that is two-fold. In The Heaven of Animals, there are two stories about Richard and Lisa Starling: “Venn Diagram” and “Wake the Baby.” And the Starlings have a daughter, June, who dies after a month. I wrote the first story and didn’t think there would be a sequel, then I wrote the second story, which takes place a couple of years later, when they have a second child, a son. I didn’t think I’d return to them again, but they kept haunting me until I wondered where they’d wind up 35 years later. Did their marriage survive? Did they have a third child? And so on. When I finally started writing about them again, I realized I was writing a novel.

The second part of that answer comes from an incident on the Fourth of July, back in 2008. I was on Lake Oconee, in Georgia, where my parents had this small, double-wide trailer lake house. We went to a fireworks event that night. Afterward, I spotted a young boy on the very back of a boat, feet over the water. The boat was racing away from the fireworks display, and, if the kid had fallen in, he likely would have drowned in the dark or been cut up by a hundred other boats whizzing by. Luckily, just as I was trying to decide who to call or how to help, a police boat pulled the boat over. I’m sure they got the world’s most expensive boating violation ticket, but I was haunted by what I’d seen and by the tragedy I imagined. (And this was before I had kids of my own.)

It haunted me to the point that, in 2009, when I had twin daughters, I barely slept the first month. When I slept, I had nightmares about my daughters drowning. And I knew I had to exorcise these visions from my consciousness, so I wrote about a drowning. Writing, I thought this might be another story about Richard and Lisa, but I couldn’t bear for them to lose a second child. So I decided this event would be something they witnessed. The novel then became a question of: what is the role of the privileged witness to a tragedy? What do you do with that responsibility? That horror is bound to ripple into your own life and potentially trigger the PTSD of your own losses.

So, in time, somehow, those two ideas converged and became the beginning of Lake Life.

Did you use Lake Oconee as your stand-in for the novel’s Lake Christopher, then?

Did you use Lake Oconee as your stand-in for the novel’s Lake Christopher, then?

I used Lake Toxaway in North Carolina. Lake Toxaway, like the fictional Lake Christopher, is about ten miles from Highlands, and it’s about an hour from Asheville. All of the things about Lake Christopher are borrowed from Lake Toxoway: its size, its portions of development by the owners of Home Depot and RaceTrac, and all of the weird economic dynamics, plus how the land used to belong to Native Americans. I set the novel there because, as a kid, before my parents had a lake house of their own in Georgia―and we were not a wealthy family―we vacationed for a week every summer in a converted double-wide that some friends had on Lake Toxaway. That was the lake I grew up with and fell in love with as a kid, and I wanted to return to that setting in this novel.

How could you not?

It’s weird how you can spend just one week a year at a place for ten years, yet those ten weeks add up, in your imagination, to a lifetime of memories.

It’s embedded in your brain. I’m curious, then, what it was like having short stories as your primary focus, then switching over to the novel. What were the changes that needed to happen? What were the new muscles you needed to exercise?

It was utter chaos! I began writing it in earnest in 2011, then I worked on the book for nine years. I didn’t work on it straight through―I published plenty of stories and essays in lit mags during that time―but I really began the novel reluctantly and for the wrong reasons. I had finished my story collection, The Heaven of Animals, and my agent was having trouble selling it. She mentioned that if I were ever going to begin a novel, now would be the time, as novel partials can help sell story collections. Luckily, about 100 pages into the manuscript, I fell in love with these characters again, and I began writing the book for less mercenary reasons. Another 100 pages in, I was completely invested, and now I feel as much novelist as story writer. But the beginning was a challenge. I was a short story writer, and I’d spent years studying the form. I’d certainly read plenty of novels, especially while working on my PhD, but, writing a novel of my own, I began reading novels in a new way to learn the craft.

The first draft of the novel was written in past tense, then I moved to present tense. The first draft had too much Michael, then I figured out that I needed all six major characters’ points of view to be distributed evenly. The first draft took place over four days, then my editor and I realized that the first day was all summary and backstory. Chapter 11 was initially the first chapter of Part Two, when the boy falls off the back of the boat. My editor said, What if the novel begins there instead, and what if everything you’ve referenced in those first 100 pages is referred to in just a couple of sentences throughout? And she was absolutely right. That’s how Chapter 11 became Chapter 1.

Looking back at the first draft, I don’t think anyone would have read past the first couple of chapters, waiting for something to happen on page 100.

It was a great choice to start there with the two major tragedies: with the boy dying and with Michael getting injured while trying to save him. It’s relentless from then on, which is just excellent. Everything else after it is now tinged by it, and there’s just so much inherent tension through the rest of the book, especially between the Starlings and the people around them in the upper classes.

You know, the working title of the book was Class, Order, Family. But that title is maybe a little overly clever, plus we were afraid that the title might get the novel shelved with the textbooks. So while the novel is definitely about family, it was also important, to me, to show what these Southern lakes look like, the economically disadvantaged living side-by-side with super-wealthy people. One person’s prestige lake is the home of another person’s trailer. And I wanted to speak to this particular American moment of economic despair and disparity. The Starling family itself is composed of two retired academics, who are upper middle-class or lower upper-class; their son, Thad, who is destitute without the financial support of his wealthy partner, Jake; and Michael and Diane, who are, like a lot of millennials, shouldering school debt and credit card debt and the misfortune of buying a home right before the housing bubble burst. They’re representative of a generation who will do worse, financially, than their parents’ generation. Because I’m not a PoliSci guy, I haven’t proposed any answers to this problem. But I wanted to write about the world around me, as I see it. The book was never going to be about a Martha’s Vineyard family or a Hamptons family―and don’t get me wrong, I love those novels, too―but this is the world I know: double-wide trailers, Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas.

Honestly, this is one of first books I’ve read that has put this situation up to the light: of one generation not doing as well financially as their parents. And again, so much of the conflict happens because of this disparity. On the lake, in town, in the bars and galleries. So much excellent tension came from this.

I was going to ask, as well, about the amount of attention you give to visual aesthetics in the novel. Visual art in the forms of paintings and comic books comes up frequently, along with questions about what we can look at, what we can’t look at, etc. I was curious about what your background was in visual art.

Before I was an English major—as an undergrad at Berry College in Rome, Georgia—I was an art major. And before I was a reader of literary fiction, I read comic books. I was a resistant reader growing up, and it drove my mother crazy. She was a librarian, and she finally tricked me into reading through comics. Nowadays, it seems silly to make the point that comics have value. We all recognize the art of graphic narrative, and we all recognize the value of sequential art. But growing up as a kid in the ’80s and ’90s, that understanding was not the prevailing attitude. I had teachers tell me that comic books were garbage and didn’t count as ‘real’ reading, but comics certainly got me to read, and I can never thank my mother enough for making them a huge part of my life.

I loved comic books for their stories, but I also fell in love with the illustrations and art styles. I can still go to a comic book store today, walk past the racks, and tell you things like, “Oh, that’s a Todd McFarlane, that’s a Jim Lee.” I can still pick out any comics artist from the ’90s in a glance. I have a decent eye, and I wanted to be a comic illustrator, but I burned out on drawing pretty quickly after a couple of college classes. Drawing was my hobby, but it turned out not to be my passion. I can sit in front of a computer for ten hours straight and not drive myself crazy, but if I sit down to draw, my hand cramps after a couple of hours and I start to hate what I’m doing. It’s anxiety-provoking. I still sketch for fun, nothing at stake. I love art. I love comics. And, try as I might, I couldn’t keep that Lisa/Thad comic book narrative from invading the novel.

I’m guessing that, like your character, Thad, the X-Men were some of your favorite comics growing up?

Absolutely. But the hardest thing about writing Thad was that he’s so much younger than I am, so his X-Men experience is different from my own. For me, the X-Men were the late Claremont period to Scott Lobdell and Joe Madureira, whereas those books would have been too early for Thad.

Right. Thad would have been the 2000-2010 period. Matt Fraction and all the rest, which I totally missed.

Exactly. I’ve read Fraction’s work on Hawkeye and Sex Criminals, both of which are brilliant.

Sex Criminals! Yes! It’s one of those wonderful titles that I absolutely can’t justify having at my house with small children, but I do anyway. It’s so incredibly good.

It is! It even won an Eisner Award, which is like the comic book equivalent of a National Book Award.

That reminds me: I wasn’t sure if your experience was similar to Thad’s and how Lisa saw her son’s attachment to those characters. What was it about the X-Men that resonated so strongly with you, then?

Like many young, bookish kids, I was definitely picked on in elementary and middle school. I dealt with a lot of bullying because some kids thought I was gay. That didn’t turn out to be the case, so I want to be clear that I’m not saying that I know what it’s like to be gay or to be persecuted for my sexuality, but I know what it’s like to be in fights, to be called gay slurs, and to be bullied. The X-Men titles were a safe place to be yourself, peopled with characters who were hated but were also heroes.

I could never identify with Superman. I couldn’t identify with Captain America. I mean, how do you identify with superhuman, everyone-loves-them, perfect, musclebound, masculine characters when you’re a boy with glasses, no muscles, a belly, and a high-pitched voice? But when it came to the X-Men, everyone hated them while they were just trying to do the right thing, and that resonated so much with me as a bullied, middle-school kid.

This feels very, very familiar.

And even though this is inside baseball, I couldn’t withhold my indignation about the direction the X-Men took when Grant Morrison took over. The novel features a brief, rage-filled moment about how Morrison destroyed the X-Men. The scene involves a comic book store employee discussing how Morrison changed the series’ dynamic. The whole Morrison storyline of a Caucasian Magneto pretending to be Chinese was really messed up, and that, in part, spoiled the series for me.

I’m pretty sure that’s where the series ran out for me, too, with my own boxes of comics, which are probably still sitting in my own parents’ house right now. Similar to that, I noticed that you had several scenes with your characters in these very small, confined spaces. For example, the lake house itself is a converted double-wide trailer, then there are these intimate scenes in places like the bathroom, the front seat of a car, the garage where Lisa stored Thad’s old comics, and the like. Here’s my question, then: do you see the current pandemic as reshaping how we view physical space and intimacy in fiction?

Yeah, how can you not? You only have to look to the news to see the spikes in divorce rates. Then, of course, people are forming new intimacies. I have a friend who was just three months into a relationship when the pandemic began, and the two of them decided to lockdown together, and they’re still together, three months later. It’s been amazing to watch how quickly relationships can evolve, or disintegrate, when two people are pressed into close quarters for months at a time. I think it’s true, too, that anytime families find themselves together for more than a few days, there are going to be numerous hurts and old feelings that surface.

For the characters in this book, a converted double-wide trailer doesn’t offer a lot of privacy. I wanted to structure the novel in such a way that, after they’ve spent a couple of days together, they all break off from each other on the third day.

It was great. Like watching tigers all on the prowl in the same cage. It reminded me so much of those family gatherings where everyone spends just the right amount of time around each other, to the point where no one questions the decisions to break off and away the day after. This was another thing that felt so natural and familiar.

And you’ve also got these characters who, when they’re confronted in these tight spaces, begin to reexamine their political decisions from back in 2016, two years before the events of the book take place. Have you been encountering people like this where you are in Florida? People who’ve tried either to justify their vote or apologize for it?

Yeah, absolutely. And not just in Florida, which is a purple state, but in Georgia, too, with high school friends or college friends, and some family. Some have definitely lamented their decision to vote for Trump. Others have lamented their decision to vote for Stein. Others are actively defending their choice and will, somehow, maddeningly, vote for Trump again this fall.

Writing this novel over the course of nine years, I was operating under the delusion that it’s possible to write a “timely” novel. I don’t think that’s possible, in 21st-century America, because everything changes every month. This is a novel about three relationships, and one of my goals was to make an argument for gay marriage. Then, in 2015, happily, gay marriage was legalized, and my argument was no longer necessary. Then, many of the political conversations during this period had to do with Obama versus Romney, or Obama versus McCain, both of which became terribly uninteresting after this monster took over the White House.

But once I set my mind to it, and while I was taking my last few passes at the novel in 2018-2019, it became clear that this book needed to launch in the summer of 2020 because everything changes so quickly. If it came out after the 2020 election, so much would feel irrelevant. Even as I say this, with the pandemic at its height, and all of these long overdue and necessary civil rights conversations happening, along with the murders of people of color, the novel will probably still feel irrelevant in a number of ways.

I no longer think it’s possible to try to write a timely novel. But since the novel is set in 2018, at least people will be able to look back at it years from now and say, This is what life looked like in the first half of the Trump administration, back when we knew things were bad but before we knew just how bad things would get.

The conversations among the characters really help create that timestamp. Looking toward the future, then, I was curious about a project that you have in mind that you want to write but which seems intimidating to you. What’s the monster you know you have to meet down the road?

Well, the next book hopefully―it’s with my agent now―is another collection of short stories. Since The Heaven of Animals, I’ve written over twenty new stories. But we’re waiting to see how the novel does, how the world is, and how New York City is after this summer. I’m fairly deep into another novel as well. I can’t talk much about it, but it’ll be a big Florida novel. I was hesitant to set a novel in Florida until I’d lived here long enough, and now that I’ve lived in Florida for nine years, I have something to say. Plus, Florida is enjoying a wonderful, literary moment. There are so many great Florida-native writers here that I want to be careful about stepping on any toes.

The new novel takes place over two days. I have an idea for a third novel set on a single day. I’m obsessed with compression. Who knows? Maybe my fourth novel will take place over the course of an hour.