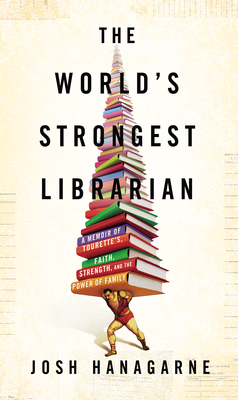

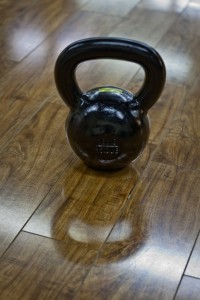

Josh Hanagarne’s desk on the third floor of the Salt Lake City Public Library is the one with the black, globe-sized kettlebell on it. The kettlebell is all bell and no whistles. In his book, The World’s Strongest Librarian, Josh writes about swinging them in various trajectories to work the muscles in a way that ordinary weightlifting can only begin to. I’m a pretty strong guy, so I give it a try. I realize that I clearly haven’t given the kettlebell the respect it deserves because, on my first attempt, it doesn’t even leave the desk. On the second try, I can lift it, but I put it down again as soon as possible so I don’t hurt myself.

Josh has cleared some miscellaneous items from a conference table in a corner room and we sit and talk craft.

Interview:

Aaron Cance: If my memory serves me correctly, you wrote a good piece of this book before it was sold to Penguin, and you then had a deadline to produce the rest.

Josh Hanagarne: Yes, the first five chapters were a majority of the proposal. They stayed relatively untouched in the final version of the book. After that, I had eight more chapters to do that were outlined in the proposal. I had a year to write and edit those eight chapters so they would fit the entire piece.

And did what you finish with differ from what you had conceived at the outset?

Yes, but the biggest changes in the book were substitutions. For example, this was going to be a book about how I had gotten rid of the tics, but they returned. Also, the chapter about faith was never really meant to be in the book. There was a full chapter about a trip to a Navajo reservation where my grandfather lives that got cut.

Did you notice a difference in how you approached your work before it was sold versus afterwards?

Not really. The only real difference was that I was working with a different editor. The first five chapters were written by me and were then worked on by an editor who did freelance work. We sold it, and I had to write the next eight chapters with the buying editor. I wrote the next eight chapters so she could see it all at once, and that was definitely different. There was no chapter-by-chapter feedback for the first draft of the final eight chapters.

Were your writing habits, or schedule, different before and after The World’s Strongest Librarian sold?

No. I write when I can, both when I have time and when the tics will let me. If I’m trying to create new text, I can generally create for fifteen to thirty minutes a day. If I’m revising or moving stuff around, and have the time, I can usually work for a couple hours.

The World’s Strongest Librarian is a multifaceted book. It’s autobiography, it’s about your experiences with Tourette’s Syndrome, it’s about your skirmishes with your faith, it’s about family, it’s about weightlifting, among many other things. How did you conceive it vs. what was on the paper when the manuscript was finished?

I thought it would have less of the content about faith. When I started the book, I was still going through all the motions, and was okay with that, but as I continued to work on the book, and was forced to deal with how I feel or what I think about my faith, and what I really believe, and [I started to ask], “Do I know why I believe what I do?” I realized that it had seeped into everything, and that I’d have to figure it out. If you really want to know what you think about something, try to write it down on a piece of paper. You won’t feel as smart or as well-reasoned as you did when you started.

The content about your faith doesn’t seem to have really displaced any of the other topics in The World’s Strongest Librarian. It just became another of the book’s subjects.

The content about your faith doesn’t seem to have really displaced any of the other topics in The World’s Strongest Librarian. It just became another of the book’s subjects.

The whole thing started out a consideration of all the facets of curiosity. At the end of the day, I think that this is a book about questions and curiosity.

So your notion of what you wanted it to be really didn’t change over time as it was produced.

Not really. I never had any illusions about the perfect way to tell the story. I knew that I would select a bunch of things and would say, “This is what happened to me,” and see if there were any connections between them.

As I read your book, it struck me as brave. You’ve really opened yourself up to your readers.

I don’t know that there’s anything courageous about it—nothing scared me. When I’ve tried to pretend that things are anything other than what they are, it hasn’t gone as well.

What parts of the book surprised you? What emerged that you hadn’t expected to?

Honestly, there wasn’t much of a plan beyond the initial outline. The threads of the story are all so weird that even having a chapter outline that said we were going to go from here to there didn’t really feel like a guarantee that it would happen. Once I got started, though, I was surprised at how easy it was to write.

I’ve been following your posts on the World’s Strongest Librarian blog, and you have a remarkably generous position about criticism. Tell me a bit about your approach to negative feedback about your book.

Well, there really hasn’t been much that I’m aware of, but if you put something out into the world, people get to react how they want, and I don’t think that praise or criticism are really worth taking personally. Someone writing that my book is good doesn’t necessarily make it good, and someone writing that it isn’t doesn’t necessarily make it bad. I’m a reader, too. Every reader’s reaction is probably the right one for them.

You’ve done some events for this book with young people with Tourette’s Syndrome. Tell me about that.

You know, I’ve done a lot more speaking work about Tourette’s outside of the book tour. There just happened to be some stops on the tour where parents have brought their kids and I’ve seen them. That’s the best thing for me.

It must be rewarding to help guide young people through some of the challenges that you’ve faced alone, and have had to face in a different time, when people were clearly not as widely informed about what Tourette’s is and how to live with it. How has that shaped you, or changed your life?

I think it’s really good for kids to see someone with symptoms way worse than theirs, out doing something like this in public. I definitely wouldn’t say that I’m guiding anyone. I wouldn’t really be comfortable with that. I think the parents who come get more out of it than the kids do, in some ways. They get to hear about my parents and the things that, ultimately, made the difference for me.

As far as your family acclimating to the Tourette’s as an insistent presence in your life.

My parents just wanted to get the support that they needed to make me feel safe, to get me to the point where I could handle it alone. Parents I’ve talked to at speaking engagements or on the tour often ask me what they should be doing. I don’t have that answer but I know how they feel. The parents asking those questions, however, always seem to be doing the things that she should be already. I’ve seen some parents start to cry when I give their kids my phone number.

Moved by the sense of support?

Moved by the sense of support?

It’s the sense that someone cares. This story is not really a story about someone who overcame something. It’s about someone who’s still in the middle of it, and is still dealing with it, and is not afraid to say, “This is horrible, and it’s not fair, but so are a lot of things. So what do I do now?”

You’ve told me before that one of the things that your book tour did for you was to remind you just what a big part of your life writing really was.

It definitely feels like something’s missing when I’m not writing.

When we had lunch a few weeks back, you spoke about a couple possible projects that you’d like to move onto next. Have you given that any more thought?

Yeah. I’m working on a children’s series called The Boy Who Knew Everything. I’m fairly deep into that now. The other idea that I have for a follow-up nonfiction book, but its production would depend on other peoples’ schedules, and it’s a little more tentative because of that.

And, as a reader, what are you working on now?

I’m always reading Mark Twain . . . and I’ve just started The Keeper of Lost Causes by Jussi Adler-Olsen who, according to the endorsements on his dust jacket, is “the new ‘it’ boy of Nordic Noir.” The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner, and I’d like to read everything that Kate Atkinson has written. Two other books that are on the horizon are the Pierre LaMaitre book you’ve mentioned, Alex, and The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion.

And now you have your complete Mark Twain set back! At one point, and this is a story that you share in your book, you sold that set to raise money to go to a kettlebell event in Minnesota?

Yep. That trip cost about two thousand dollars.

That had to have been heartbreaking.

I love that set.

And, just recently, a complete Mark Twain set showed up at your house again?

My editor and my agent, as well as the editor that I worked on the proposal with, replaced the books. They got me into a conference call one day. They tricked me into thinking I was in trouble for something. When they got me on the line, they said, “We’ve replaced your books. Stop whining. They’re on your shelf at home.”

And now you can read Twain this summer?

Yep. I tend to move through the whole collection and, when I’m done, start over at the beginning again.

Now, after being without them for such a long time, are you going to start at the beginning again? What’s the next Twain on the docket?

[Josh smiles easily, thoughtfully. I read a couple possibilities into his expression and his answer. Maybe the field of his options is too rich to narrow without giving it some thought. Maybe his relationship with Mark Twain is something too long-standing and personal to explore in this interview.]

I really don’t know.