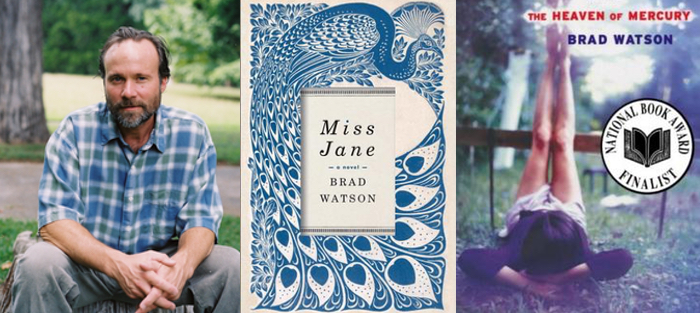

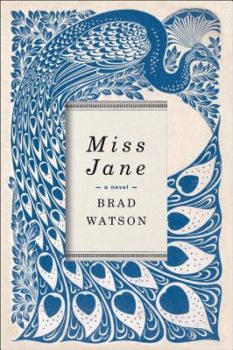

Brad Watson has long been known for upending readers’ expectations, and in his most recent novel, Miss Jane (W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), he does just that, often blurring the line between what is normal and what is not, what is bad and what is not. The result is a story that is as real as life, without sentimentality and without fear of delving deep into the lives of his characters.

Miss Jane is based on the story of Watson’s great aunt, Mary Ellis (Jane) Clay. Due to a birth defect, Jane was incontinent and never able to have children, so she never married. A lot of research went into diagnosing Jane’s condition, and exploring the time during which the novel is set.

The town of Mercury is Watson’s fictional landscape, and this is where both Miss Jane and The Heaven of Mercury (2002) are set. Like Faulkner, Watson has staked out his fictional terrain, and created characters deeply reflective of their own time and place.

Watson is also known for the short story collections Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives (2010) and Last Days of the Dog-Men (1996), but in this conversation we focused mostly on his novels. In particular, Watson spoke about his origins as a writer, his creative process, how he approaches his subject matter, and some of the surprises and challenges that arose during the writing of Miss Jane and The Heaven of Mercury.

If you haven’t read any of Brad Watson’s books, you’re missing out on a treat of a literary journey.

Interview:

How did you get started writing and what did you do to develop your craft?

I took an honors English class at my local community (then called “junior”) college. It was taught by Niles “Buck” Thomas, who’d studied under Madison Jones at Auburn, and his field was Southern literature, specifically fiction. For the first time, I read great books seriously, with attention, with excellent guidance, with enthusiasm. It was an awakening. Before that, I’d been a juvenile delinquent, as they used to call it, and married my pregnant girlfriend between junior and senior years of high school, went to work at about 35-40 hours a week while finishing high school, then hauled off to L.A. to try to get into the movies. I’d done a lot of local theater, my one worthwhile passion, so my dad thought I should just go for it. But when we got out there, the writers went on strike and shut down the industry, and I ended up in various labor jobs, including Hollywood garbage man.

We came home when my older brother was killed in an accident. I went to work in my father’s dive bar, and then my families talked me into going to the junior college. I didn’t think I had the smarts for it, but I CLEP [College Level Education Program]’d into this honors class, and next thing you know I was swooning over novels and short stories, wanting to become a writer. Although that seemed like a hopelessly impossible feat for someone with my history and background, I was determined, and wrote a big box-full of bad stories over the next four years. Burned them all after a couple of years in grad school. I’d say I’ve developed my craft to whatever extent I have mostly by a lot of reading and writing. I had good teachers, but reading great, interesting work is essential. So is writing, writing, writing. Failure teaches you everything. At first it’s just perplexing, but gradually you begin to learn.

How does your reading life inform your writing life?

Reading and writing are, as I said above, our only real teachers. Everything I’ve ever read has had some degree of influence on me as a writer, has taught me something about how to do it. We don’t work in a vacuum. You can be the most observant person in the world and still be a crappy writer. Writing workshops are mostly valuable as reading workshops. They help you learn to read like a writer, and how to read your own work like a writer–instead of, say, a fatuous, callow egomaniac. If I hadn’t taken Buck Thomas’s course, though, I wouldn’t have tried so hard to become a fiction writer.

How do your stories and novels come to you: a voice, an image, a character?

In different ways. I work instinctively, at first, trying to find the voice, understand who the people are, what the problem is, get a sense of what it’s all about and why I even ought to write it. Sometimes it’s an image, such as it very much was with my story “Vacuum” in Aliens. Sometimes, too rarely, I have a sense of what the whole story should be. Often with me there’s an autobiographical core, some memory that must be re-processed, you know, in order to find the fiction or the structure of the narrative, whatever that might be. That turns out to be pretty time-consuming, because memory is kind of a conniving, manipulative force that wants to control you and everything you do, if you’ll let it. Memories can open up the idea for a story, but they can just as easily shut down the imaginative journey into it. Nevertheless, I think it’s true what a friend once said about me, that I don’t really write a story if there’s not something very important to me in it or about it. So, a lot of it is born of my experience, and undergoes that particular alchemical change along the way to being finished. I never finish, though. I read a story from my first book recently, and before the reading I did a pretty good edit on it.

In different ways. I work instinctively, at first, trying to find the voice, understand who the people are, what the problem is, get a sense of what it’s all about and why I even ought to write it. Sometimes it’s an image, such as it very much was with my story “Vacuum” in Aliens. Sometimes, too rarely, I have a sense of what the whole story should be. Often with me there’s an autobiographical core, some memory that must be re-processed, you know, in order to find the fiction or the structure of the narrative, whatever that might be. That turns out to be pretty time-consuming, because memory is kind of a conniving, manipulative force that wants to control you and everything you do, if you’ll let it. Memories can open up the idea for a story, but they can just as easily shut down the imaginative journey into it. Nevertheless, I think it’s true what a friend once said about me, that I don’t really write a story if there’s not something very important to me in it or about it. So, a lot of it is born of my experience, and undergoes that particular alchemical change along the way to being finished. I never finish, though. I read a story from my first book recently, and before the reading I did a pretty good edit on it.

You set many of your narratives in or around a fictional town, Mercury, Mississippi. You’ve said, “That place is imprinted so strongly in my memory that it has taken on a kind of life independent of fact or real history—although what I recall as real is a solid and fertile imaginative landscape or place.” Why did you choose to create a town rather than depict an actual town?

This goes back to what I wrote above about the limitations memory can impose upon imagination. If I allowed or forced myself to act more like a journalist in terms of my depiction of my hometown, more like a journalist than a novelist, what do I gain? Nothing, in terms of the imaginative space created for the work. You get to use what’s really there, in terms of physical place or history, if it suits the story; and you get to ignore what isn’t necessary; and you get to invent what’s not there that you need. It seems important, though, to have something real that can work as the mash, so to speak.

In the beginning of your most recent novel, Miss Jane, you tell us that the book was inspired in part by circumstances in the life of your maternal great-aunt. How did she inspire you to write this story, and how did she inform the main character, Miss Jane?

That’s a big one. My fascination with my great aunt Jane Clay began when I was a young boy visiting my grandmother in the country one Sunday and there was (for us children, anyway), an unexpected visit from a very old woman dressed in black, with a black hat and veil, helped from the car to the house by someone, a gentleman I cannot recall. Someone said, “That’s Aunt Jane.” We knew there was something special about her. She lived alone, had never married. “Something is wrong with her,” others said. Over the years I, we, came to understand she’d been born with a birth defect, apparently urogenital in nature, that rendered her not only incapable of marrying but also left her incontinent her entire life, thus imposing some further degree of isolation.

Then, when I was in my twenties and going through a divorce–I’d eloped in high school with my pregnant girlfriend, beginning a lifelong complicated relationship with love and marriage–I was at my mother’s going through an old shoe box of photographs and came upon one of a young woman or older teenage girl, in a dark summer dress, wearing a broad brimmed hat, looking over her shoulder at the camera with what I thought was a flirtatious, even a kind of come-hither look, you know. When I asked my mother who it was, she said, “Oh, that’s Aunt Jane.” When I wondered who took the photo, as it looked like she was flirting a bit, my mom said, “Oh, she was popular with the boys. She used to go to the dances at Damascus Community Center.” Okay. This is the girl who became the woman my mother said used to “squeak when she walked,” making the kids laugh, because of the rubber protective garment she had to wear over her diaper. How did she manage, I wondered, to go to dances, to be popular with the boys? And furthermore, and more important, how did that end up for her? How was it when she got a little older, was no longer a girl, knew she could not marry, when she had to stop going to the community dances–when, effectively, she had to step back and accept the role of an “old maid.”

My mother and aunts and uncles all said Aunt Jane was a cheerful person, who loved children. She did not seem to them like a complicated person. On the other hand, while I was working on the novel, one of my older cousins remembered that when Jane would visit their house, she would disappear into the bathroom to wash her undergarments behind a locked door, and would not allow them to be washed in the family’s old washing machine. I realized that Great Aunt Jane’s life had to have been a lot more complicated than people realized or let on. One day I went searching for her gravesite, and returned to tell my mother I’d found a stone for one Mary Ellis Clay, with the right dates, but no Jane Clay. “Yes, that was her name,” my mom said. Why did she go by Jane? “I don’t know. That’s just what we called her,” Mom said. And, apparently, others called her Aunt Mame. I could see “Mame” coming from Mary Ellis. But Jane? That was a nice mystery, too.

Even so, no one alive knew what Jane’s exact condition had been. And there were no surviving records. A lot of the time I spent unable to figure out how to write Jane’s story as a novel was taken up with reading long, old urology texts and searching on line for a condition that might match what little I knew about Jane’s: She was incontinent, apparently unable to conceive and probably unable to have sex, she had just one opening for everything (this she confessed to my mother’s older sister on her death bed), and apparently her condition was beyond medical science’s ability to repair, at least in her time.

I knew she lived on the farm with her parents until she was about forty years old, then moved to town when Welfare became available. We presumed she took advantage of it to survive. She traveled frequently, by bus, to see her brothers and their children in other states, mostly east Texas but also Virginia during World War II. She died in a rest home that no longer exists.

I was a young man who’d had more love affairs than he deserved, and who wasn’t very good at being a partner, despite being given every chance to be that. And here was my great aunt Mary Ellis “Jane” Clay, apparently a survivor of a life in which she was denied the chance to have a love. But, then I wondered if there was a story behind that.

Yet despite romantic or sexual relationships, Jane does have an erotic connection with the natural world:

All things of this nature…torrential storm, the burst of salty liquid from a plump and ice-cold raw oyster, the soft skins of wild mushrooms, the quick and violent death of a chicken, the tight and unopened bud of a flower blossom, a pack of wild scruffy dogs a-trot in a field, the thrum of fishing line against the attack of a bream, and peeling away the delicate frame of its bones from the sweet white meat of its body…the somehow palpable feeling of fading light–were in some way sexual for Jane.

How did you discover the natural world as a way to enter Jane’s sexuality, and what were the challenges in writing this?

Well, when you’re searching for a plot in a story concerning a girl (and later, woman) with a condition that keeps her fairly isolated on a farm in early twentieth century Mississippi, you kind of have no choice but to consider her relationship to the natural world. When I was a boy, I was kind of a loner, a daydreamer, and I often went off alone into the woods near our home. It was comforting to me, and beautiful, and even magical in a strange way when you were in the woods, in the quiet there with only birdsong and the little sounds of animal life here and there. So I thought Jane may have found a similar comfort, and may have needed it even more than I did. Possibly much more. So, I wrote into that to see what I would find, and kept finding more.

Where Jane is not physically sexual, and will never be, her sister Grace is very liberated. She moves away from the family farm when she is young to take up a life in town. What did you want to show by juxtaposing two such different women?

A writer friend noted that Grace is a great foil for Jane, and I agree. The story wouldn’t be nearly as interesting if Grace weren’t there while Jane is growing up and then entering adulthood. Where Jane is naïve, Grace is worldly; where Jane wants to be loved and to please, Grace wants sex and escape; where Jane wants family, Grace wants independence, to be left alone. Grace teaches Jane a lot about how to be tough enough to survive, and teaches her some hard lessons about herself (Jane) along the way. Their father teaches her, oddly enough as he is one of those who has a hard time with demonstrative love, how to be kind. Her mother is a lesson in caution, about how not to let the world destroy your spirit. The doctor, of course, teaches her not only kindness, but patience, generosity, selfless love. And how to have fun every now and then, too. How to enjoy life, best you can.

Fundamentally, though, Grace helps to spice up the story and introduce Jane to certain worldly realities that, otherwise, she might not understand as well if not for her sister.

In response to why she’s choosing to work in a brothel, Grace says, “I don’t want to sling hash or hamburgers, or clean rich people’s houses, or work in some filthy factory.” Uneducated women didn’t have many choices, and often throughout time, women have chosen sexual service work. Were you commenting on this?

Sure. Grace is a feminist ahead of her time, and I think a lot of working women in those days were just that. It doesn’t hurt Jane, either, being exposed to the example of such a strong woman in the form of her sister. Even if Grace seems difficult at times, I don’t think it ever seems unreasonable that she would be so, certainly not from her point of view.

I watched my mother provide for our family when my father was out of work, after nearly having his spirit broken by a business that was stolen from him in the mid-sixties. It was devastating and I don’t think he ever recovered from that. After that debacle, my mother went to work in a medical clinic as a clerk and stayed with that and an adjoining surgical clinic for some thirty years. I remember her supporting us on half what my father made, remember a lot of bulk shopping, green stamps, coupons, picking and canning or freezing a ton of fresh vegetables in the summer, using friends’ gardens who were very kind and generous to her, to us. If she hadn’t been so frugal, worked so hard, we would not have eaten very well for a long time, there. My mother had one of the sweetest, most tender natures in a person I’ve ever known. But she was also very, very tough when she needed to be (which was a lot), and she was not without some anger over the fact that her life had not gone as smoothly as she’d hoped it would when she married a man from town (she, like Grace and Jane Chisolm, grew up in the country on a cattle farm), a man whose family was up-and-coming until my father’s business failure brought it down.

Moving to a different topic, you thank your granddaughter Maggie in the acknowledgments for saying, “Pappy should put a peacock in there.” You said that it changed everything. How?

My daughter-in-law wrote to me that, for some reason (I guess they’d been talking about the book, which was still very much in-progress, and no doubt Maggie was asking questions about it, about the real Aunt Jane, and so on) Maggie just popped out with that. It was funny. But I thought, well, why not? I’ll give Jane a peacock. So I did. Or, in the story, the doctor gave her a pair as a present. (I was still struggling with the plot, as you can see.) But that wasn’t working so well, seemed kind of forced or heavily symbolic in an odd way. Then it occurred to me that the doctor, having lost his wife in the flu epidemic, and being a bit of an eccentric anyway, might well decide on a whim to buy a flock of peacocks for himself. In the prism of his character and life, his own homeplace with its adjoining large tract of woods, the presence of the peacocks seemed more natural. If there is symbolism about them, and surely there is (I try not to go there in my thinking as a writer–I go with Flannery who said sometimes a wooden leg is just a wooden leg), having them exist in the slight remove from Jane’s own life on the farm is a more commodious condition, if you will. And then it worked so well for them to get fruitful and multiply, migrate through the woods and farms up toward Jane’s place when she’s older and alone. And then, of course, it kind of evolved that their presence on her farm, existing almost in her peripheral vision late in life, gives way to the last scene in the book, the vision of “otherworldly birds” that has gathered itself toward a proper meaning by that point. In other words, they became an important element in the convergence of emotional substance. And I had not planned or expected that at all.

My daughter-in-law wrote to me that, for some reason (I guess they’d been talking about the book, which was still very much in-progress, and no doubt Maggie was asking questions about it, about the real Aunt Jane, and so on) Maggie just popped out with that. It was funny. But I thought, well, why not? I’ll give Jane a peacock. So I did. Or, in the story, the doctor gave her a pair as a present. (I was still struggling with the plot, as you can see.) But that wasn’t working so well, seemed kind of forced or heavily symbolic in an odd way. Then it occurred to me that the doctor, having lost his wife in the flu epidemic, and being a bit of an eccentric anyway, might well decide on a whim to buy a flock of peacocks for himself. In the prism of his character and life, his own homeplace with its adjoining large tract of woods, the presence of the peacocks seemed more natural. If there is symbolism about them, and surely there is (I try not to go there in my thinking as a writer–I go with Flannery who said sometimes a wooden leg is just a wooden leg), having them exist in the slight remove from Jane’s own life on the farm is a more commodious condition, if you will. And then it worked so well for them to get fruitful and multiply, migrate through the woods and farms up toward Jane’s place when she’s older and alone. And then, of course, it kind of evolved that their presence on her farm, existing almost in her peripheral vision late in life, gives way to the last scene in the book, the vision of “otherworldly birds” that has gathered itself toward a proper meaning by that point. In other words, they became an important element in the convergence of emotional substance. And I had not planned or expected that at all.

More broadly, the difficulty of connections between people is a theme that crops up in many of your stories and novels. In Miss Jane, for example, Jane’s father ruminates, “You could look back on a love and recall so clearly when it was good, joyful, wild. And also in some gray area you retained the images and moments marking decline. How could a man keep a woman from hating him for the very thing she wanted from him in the first place?” In fact, the only relationship that truly endures in the novel is that between the doctor and Jane. What draws you to this difficulty?

Yes, it’s in a lot of the stories, and it’s certainly a major part of what makes up The Heaven of Mercury as well as Miss Jane. I suppose it’s in part that, unfortunately, I’ve been witness to and part of what seems like a lot more failed marriages/relationships than successful ones. And my nature leads me to take greater note of the difficulty in successful relationships than of the sweetness. I’m upset by conflict, even ‘normal’ conflict. I’m highly attuned to the presence of unhappiness, sadness, and when I see their opposites I’m moved to a state of speechless emotion. I’m a ridiculous idealist, aren’t I? I have been called, by one of the smartest people I know, an “emotional infant.” But there’s always the unavoidable presence of disappointment, unhappiness, failure. Unlike some of my more mature friends and relatives, I’ve never been able to easily shrug it off or accept it as a natural part of life. It’s my demon that I find difficult to embrace. Writing about it is about as close as I come to that, I suppose.

The title of your first novel comes from Dante’s The Divine Comedy. What drew you to that as a source for The Heaven of Mercury?

Truth is, I don’t recall what first led me to Dante when I was working on The Heaven of Mercury. I think it may have been a rather idle looking around for references to Mercury–the god, the planet, the element–that led me somehow to The Divine Comedy. And when I saw the chapter entitled “The Heaven of Mercury,” I knew I had my title, since so much of Mercury is about the strangeness of being alive, mortal, and what seems to me the strange and fine line or vague lacuna between life and whatever comes after (and even, in the book, before). The idea of Heaven having been so oddly simplified in church life when I was a child, you know, led me to wonder as an adult why we invented it, what kind of need it must have emerged from, and of course the odd nature of the idea of what “Heaven” might actually be. And of course if you look up or think about the various definitions and usages of the word, it’s not hard to make the leap to the idea that various heavens may exist around us and within us at all times.

You’ve said that the book was inspired by the life of your grandmother who told you a lot of stories. Did her storytelling abilities influence your desire to become a writer?

Ah, maybe. Hard to say. She certainly wasn’t the only great storyteller in my family. Just about everyone was a great storyteller. I know it’s a Southern cliché, but they were (and I don’t think Southerners own that, by the way). I will say, though, that my grandmother’s stories about her childhood (which included her too-young marriage at the age of sixteen) and her crazy marriage to my grandfather and his volatile family were the main or primary inspiration to write The Heaven of Mercury. Several of her anecdotal accounts of this or that made their way into more full-blown stories in that book.

How do you approach a project like Heaven of Mercury or Miss Jane that is inspired by someone’s life? Where do you remain factual and where do you steer into the imaginary? Are there things you choose to leave out?

I guess if you’re working with an historical figure, about whom a lot is known, then you’re probably leaving a lot of things out. But if you’re writing about characters inspired by real people, you may not know all that much. In my case, the few stories I had from my grandmother about her childhood and marriage were not nearly enough for a novel, so they really acted to seed the larger story, the imagined parts, which are almost all the parts. If the anecdote is good enough, though, and you have a good sense of that person, her voice, her sense of her own life, then actually you have quite a substantial piece of material to work with. That’s the way it was with The Heaven of Mercury, even though there are several other characters who suffered either a great deal more invention or were entirely invented.

I guess if you’re working with an historical figure, about whom a lot is known, then you’re probably leaving a lot of things out. But if you’re writing about characters inspired by real people, you may not know all that much. In my case, the few stories I had from my grandmother about her childhood and marriage were not nearly enough for a novel, so they really acted to seed the larger story, the imagined parts, which are almost all the parts. If the anecdote is good enough, though, and you have a good sense of that person, her voice, her sense of her own life, then actually you have quite a substantial piece of material to work with. That’s the way it was with The Heaven of Mercury, even though there are several other characters who suffered either a great deal more invention or were entirely invented.

With Miss Jane, I had a harder time–a lot less to work with in terms of known history, deep familiarity with place, facts, anecdotes even. Very little. My aunt’s very serious birth defect, urogenital in nature, for instance: No one still alive knew what exactly it had been. People just didn’t talk about things like that. I had to do some detective work to come up with my best educated guess. I settled on a very rare (1 in 20,000 – 25,000 births) condition that wasn’t treatable, or curable, until 1982, seven years after my great aunt’s death, and the year my character Jane turned 67 or 68 years old, too late to do her any good in her own opinion. Then you had the problem of how to devise a plot for an isolated child, then young woman, living on a farm in rural Mississippi in the early-to-mid twentieth century. I had a few anecdotes from my mother about growing up on such a farm in the ‘30s and early ‘40s, but not many. So again, you begin to invent other, supporting characters, try to put them on converging lines, collision courses, and see what happens. Try to create interesting problems that then you, the writer, can write into in trying to solve.

This notion of building out stories from various family anecdotes reminds me of something Jane Smiley once said: “[An] unconscious power is often tapped through the act of description, and unexpected story revelations can spring out of the physical details of a scene.” Do physical details ever lead you deeper into a story?

I have a friend who taught writing for some thirty years, and he began his introduction to first-time fiction writers with a lecture on the use of detail, saying nothing was more important in terms of making your story come alive on the page, feel authentic, rivet the reader’s attention. I think that’s true. The hard thing, for beginners and veterans alike, is choosing the detail that’s not only vivid and arresting but that also corresponds to everything else going on in the story and with the character. That evokes the reaction in the reader you want it to. That makes perfect sense in the moment, somehow.

But to address what you ask about whether physical details can lead you deeper into a story: Absolutely. In fact, they may have more power to do that than anything else. I can think of certain passages in McCarthy’s novel Suttree that make the world off the page disappear. In Eudora Welty’s remarkable story “No Place for You, My Love,” the physical details of the land and people they encounter in the bayou country below New Orleans are the means by which she taps the strangely powerful erotic current running between two essential strangers in that car. In Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, the claustrophobic features of place pull you right down into Scobie’s suffocating life.

In your teaching experience, what are some of the common problems you see in the work of new writers?

In undergraduates, what I see is a lot of very young writers who don’t really know what to write about, yet. That’s okay. The more mature among them do have a sense of story, and that’s because they’re reading good fiction. Sometimes it’s because they’ve already undergone some deeply serious experience, as well. Sadly, most of the inferior work I see in the undergraduate classroom involves fantasy, monsters/horror, horrific (often unrealistic) crime. Not as much sci-fi as I’d have thought, curiously. Of course there’s nothing wrong with working in or between or among genres–I would never forbid anyone writing any particular brand of story, and I read a fair amount in most genres, literary and popular–but I have to say I counsel them to at least try straight realism, since it allows them to learn the basic skills without the additional complications of, say, the supernatural. It’s hard to write good so-called “genre” fiction if you don’t have the basic fiction writing skills mastered, and often it’s a recipe for confusion, lack of focus, lack of interesting characters (thinking that a great idea for a story is enough, and kind of forgetting that you still need interesting characters, vivid descriptions, arresting scenes, good dialogue, control over point of view, and so on). That said, I love the way writers these days are bending realism, even ignoring what’s so long been considered genre barriers in fiction. So, I encourage them to write what they want to write, but urge them to master the fundamentals first and foremost.

In undergraduates, what I see is a lot of very young writers who don’t really know what to write about, yet. That’s okay. The more mature among them do have a sense of story, and that’s because they’re reading good fiction. Sometimes it’s because they’ve already undergone some deeply serious experience, as well. Sadly, most of the inferior work I see in the undergraduate classroom involves fantasy, monsters/horror, horrific (often unrealistic) crime. Not as much sci-fi as I’d have thought, curiously. Of course there’s nothing wrong with working in or between or among genres–I would never forbid anyone writing any particular brand of story, and I read a fair amount in most genres, literary and popular–but I have to say I counsel them to at least try straight realism, since it allows them to learn the basic skills without the additional complications of, say, the supernatural. It’s hard to write good so-called “genre” fiction if you don’t have the basic fiction writing skills mastered, and often it’s a recipe for confusion, lack of focus, lack of interesting characters (thinking that a great idea for a story is enough, and kind of forgetting that you still need interesting characters, vivid descriptions, arresting scenes, good dialogue, control over point of view, and so on). That said, I love the way writers these days are bending realism, even ignoring what’s so long been considered genre barriers in fiction. So, I encourage them to write what they want to write, but urge them to master the fundamentals first and foremost.

And that said, I also recognize that Ben Marcus and George Saunders have said they simply never could write straight realism, just couldn’t make it work. Wasn’t, isn’t their thing. So, as I’ve implied, there are no entirely solid rules.

Among the graduate students–most if not all of them I work with are excellent writers already, when they get to our workshops. Common problems are hard to identify, because for the most part they’ve already distinguished themselves from other writers, to some degree. All of them understand it takes a lot of hard work, and usually a lot of revision. They understand rejection, resilience. Sometimes, you’ll see a writer capable of more than she’s doing at the moment, who’s not risking enough or reaching far enough, not trying to write beyond her obvious abilities. Their peers, though, will usually cure of them of that reservation pretty quickly, and challenge them in good ways.

What would you say to new writers working on their stories or novels?

When another, older writer gives you advice about how to write, be respectful (if it’s given respectfully), but you might be smart to be a bit agnostic. Especially if that advice is dispensed as if it were being brought down from the mountain on stone tablets (then you might be actually skeptical). A lot of the time, one writer’s advice may not be very good advice for you. After all, there are a whole lot of ways of going about it, and if you’re any good then you’re not entirely like any other writer. Take what help and advice makes sense, but make your own way, with confidence, tenacity, and determination. And try to enjoy it.