“Good and evill we know in the field of this World grow up together almost inseparably; and the knowledge of good is so involv’d and interwoven with the knowledge of evill, and in so many cunning resemblances hardly to be discern’d, that those confused seeds which were impos’d on Psyche as an incessant labour to cull out, and sort asunder, were not more intermixt. It was from out the rinde of one apple tasted, that the knowledge of good and evill as two twins cleaving together leapt forth into the World.”

-John Milton, Areopagitica

Posthumous. The word has always seemed laudatory to me. I think William Gay would have preferred Post-Mortem. I think he would have liked the cadaverous self-effacement of the phrase, its mischievousness.

From talking with those who knew this writer well, especially his friend and editor at MacAdam/Cage, Sonny Brewer, I gather that William Gay was a humble man, a bit shy but with a vivid wit, and a playful streak to go along with it. I think his facetiousness is important to understand in this latest book. He clearly found a lot of joy in his work, and if you take him too seriously, as I think many readers do given his often grim subjects, you may miss the significance of The Lost Country altogether.

I don’t think this book is William Gay’s long-lost masterpiece, as some have said it is. I have come to see it as his long-lost playground, a book he worked on since the late 1970’s, perhaps the first book he worked on, and would continue working on for the rest of his life. It’s a book in which he recorded countless oddities and situations, things that got his attention, amused him, caused him to wonder. I imagine this book was a place he came to, a place where he came to express his writerly joy over the absurdity of life, especially life in the rural south, and also to ponder his particular questions about the balance between good and evil, and the culpability of the good.

In this capacity, The Lost Country (Dzanc Books) offers an opportunity to peer into a great writer’s mind over the course of some thirty years of work, a mind as awake to language and life as any mind could be. Gay seems to have used it to render a private conservatory, a southern Wunderkammer. As such, the book comes very near to auto-biography.

One can infer at this point: The Lost Country does not contain the focused internal necessity of Gay’s most admired novels—The Long Home, The Provinces of Night. Those novels display the author’s gift as a storyteller, his use of prologue and portent. In The Lost Country he is not interested in these preoccupations. It’s as if he began his writing life in his late style. Which reminds me of Bob Dylan, who sounds so old on those first records, and who at the Bill of Rights Dinner in 1963 said, “It’s took me a long time to get young.”

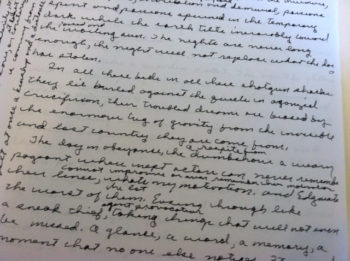

Manuscript page from The Lost Country – permission Sonny Brewer

This book also lacks the restraint in the prose of those first novels. The Lost Country can turn a shade or two purple at times, but all is easily forgiven if you have a love for these kinds of characters, as some of the rawness and rough edges no doubt had to do with the fact that Gay never had a chance to edit the project, or even work with an editor, before this book was published. It is, in fact, unedited, which is both mesmerizing and frustrating. The manuscript image at right (used with permission from Sonny Brewer), which includes the lines in which the title appears, is beat for beat what appears in the book, set down all in one line of script by its author. Incredible to see his facility with language so on display:

The nights were never long enough, the nights would not replace what the day had stolen. In all their beds in all their shotgun shacks they lay burled against the quilts in agonized crucifixion, their troubled dreams biased by the enormous tugs of gravity from the invisible and lost country they had come from.

Unlike his earlier books, or later, depending on how you see it, The Lost Country is a prolix picaresque, a book gone prodigal in almost every sense of the word, as it tracks its main characters from one trouble and escape to the next. The novel follows Billy Edgewater after he is discharged from the Navy, echoing Gay’s own biography. Edgewater begins his journey home to see his father before his father passes away. From the opening set piece—an attempt to steal a motorcycle—to the final end, Edgewater is an accomplice to the foolish projects of others. It seems he doesn’t mind. In fact, one might be tempted to think he cares about nothing at all, but there are bright flashes of his humanity in this book, moments that are tender and heartbreaking and made all the more so by the dramatic irony created by the character’s unreliable emotional state. At one point in the novel, Edgewater loses a child—it is a tremendous loss, it hangs on the character for another hundred pages, shifts his behavior and life, and yet the grief is unrecognized until just a few pages before the book ends. Gay does a masterful job suggesting this grief, allowing it to be a subterranean force in the book that finally emerges near the end like clean ground water, the swallet and resurgence, ritual of purification.

Like his predecessors in southern gothic fiction, William Gay was obsessed with the origin and problem of evil. He once said that Robert Penn Warren’s “Blackberry Winter” was a perfect story, and that if you touched a single word you would ruin it. I find it telling that it is this story Gay keeps in his mind as a true masterpiece.

Like his predecessors in southern gothic fiction, William Gay was obsessed with the origin and problem of evil. He once said that Robert Penn Warren’s “Blackberry Winter” was a perfect story, and that if you touched a single word you would ruin it. I find it telling that it is this story Gay keeps in his mind as a true masterpiece.

Speaking to those who knew him, I’m told that William Gay was not necessarily a religious man—from reading his work, you can tell he was deeply familiar with the Bible, but he was also familiar with all the books in his environment, whatever came into his hands. And so his creed was literature, from the moment he was given Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel as a teenager. From then on, he lived the life of words, whether privately as a drywall hanger, or openly as a writer at conferences and such.

And so at the center of his credo, there is Warren’s story, “Blackberry Winter,” a tale of indesinent malice, evil with no beginning and no end. A stranger comes to town, and the stranger is the snake in the garden, and he follows us all the days of our lives. That is the story of “Blackberry Winter.” Surely his admiration for it is no accident. Perhaps William Gay understood that his region was mired in this question, and that it often expressed itself best not in articulation, but in melodrama, in the garrulousness and absurdity of the south. I believe the vision gripped him, and amused him, and caused him to wonder, and that, as I have said, this book was a tool of his wondering.

On the subject of melodrama in fiction, Charles Baxter once wrote the following in his essay “Maps and Legends of Hell: Notes on Melodrama”:

Melodrama is the recognition, dramatically, that understanding sometimes fails, articulation fails, and enlightenment fails…it seems to stand on the side of enlightenment in its exposure of the corruption of the powerful and in its sympathy for the downtrodden; but it seems to stand on the side of conservatism in its assertion of constant struggle and in its belief in the perpetual existence of evil and the unknowability of its ultimate source.

It is a dark wonder, but wonder none-the-less. And this is the true meaning of melodrama, not in the one-dimensional and pejorative use of the word, but in its literary use. If characters corresponded to the contemporary notion that all human malfeasance can be understood and attributed to societal ills, and that once we have our society straight, we will have solved the human problem, the problem of evil, we would not only be revising history, we would also have a body of fiction that is full of pat epiphanies, void of all mystery and drama.

I admire what William Giraldi said about William Gay on this subject in his blurb for the book:

…his bold method of seeing the waste and wonder we are, this posthumous novel is a reminder of what we miss: the language pitched toward the sublime, his men and women grappling for redemption in a world that has damned them, his understanding of grace in the presence of human badness. When Gay died too soon, we lost much, but The Lost Country gives a piece of him back to us.

I think it was Flannery O’Connor who once said that evil is a mystery to be endured, not a problem to be solved. William Gay placed an autobiographical character—Bill, Will, not that far off—in the midst of characters who for thirty years of his life drew him into their own melodramatic and mysterious ways of being—misplaced, confusing, and confused—and so worth every consideration. It was his joy to live among them, consider them, and to endure them, one page at a time.