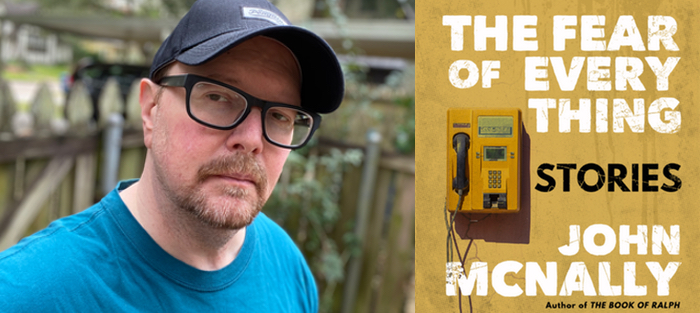

I first met John McNally when he joined the faculty at Pacific University’s MFA program. I was in my second year, and though I didn’t get to study directly with him there—we would later work together during my PhD program—I was drawn to the combination of wry humor and deep empathy he laced through every craft talk and reading. What he brings to the page is similar to what he brings to his teaching, his mentorship, and his friendship: an open heart and an unflinchingly honest perspective—and the wit to sharpen the edge of both. These are the hallmarks of his newest short story collection, The Fear of Everything (UL Press).

I read The Fear of Everything in one sitting, a thing I rarely do with collections of stories. But, from the first pages, I found it hard to pull away from the sense of tangible longing at its core. This is a book filled with characters whose failures, losses, and scrambling attempts at reinvention continue to haunt them. It is a book that bends genre and breaks expectations, where a sinister magician can make a young girl really disappear and a phone call can reach into your past, so you hear the whispers of your childhood but can’t find the right words to send a warning. Few collections hang together as a book quite as tightly as The Fear of Everything, because despite the many, many strange voices that haunt it, it is generally a book about one thing: the frightening dangers of having a beating, breakable heart.

In addition to The Fear of Everything, John McNally is the author or editor of eighteen books, including The Book of Ralph: A Novel and The Boy Who Really, Really Wanted to Have Sex: The Memoir of a Fat Kid. His craft book Vivid and Continuous has been used in many college creative writing courses. He has also had screenplays optioned and in-development, and his work for a Norwegian film company in 2019 took him to Norway’s Arctic Circle for research. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, John is Writer-in-Residence and the Dr. Doris Meriwether/BORSF Professor in English at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He is presently writing a thriller set in Thailand, where he plans to retire.

Interview:

Leigh Camacho Rourks: One of the first things I noticed was how well-crafted the order of the book is. We open it up and the first two stories make us feel afraid of the world, uncomfortable. Then we get to the third story, the titular story “The Fear of Everything,” and there’s a turn. It’s as if I was set up to understand the feeling at the core of that story: fearing everything. But, at the same time, I was utterly surprised by it because it’s not actually a scary story. Instead, it is very touching and delicate. How did the order find you? Did you have a plan?

John McNally: I never have a plan. No, I just write a bunch of stories. At a certain point, I begin to see certain patterns emerge from the stories. I always hate to use the word theme, but I see themes.

Once it gets to a point where it’s nearing completion, I begin playing around with potential orders and looking for gaps. Not necessarily that I’m going to write a story to fill that gap, but maybe there’s a way I can shuffle the stories around or ways in which, if I add a new story, that’s going to affect the order of this book. Pretty early on, I knew I wanted to begin with the story “The Magician.” I like for the first story to be a template for what the book is going to be in some way. And so “The Magician” sets the tone. But also, if anybody’s familiar with what I’ve written in the past, I write a lot about younger kids and this is like a version of those past stories but scarier.

“The Magician” really shook me. I wasn’t expecting it of you. It is so sinister and strange. It was a great way to teach me how to read the book.

Yeah, I definitely wanted a story that has a fantastical element in it to be an introduction to the collection, so people can anticipate that even if not every story has a fantastical element, the stories may be a little strange.

I’m glad you brought this up, because this is a book that really pushes and plays with genre. There’s elements of many different genres—magical realism, sci-fI and fantasy, hardboiled grit. You even play with the western genre. Can you talk a little bit about deciding to push what we expect from literary short stories?

Probably around 2011, a friend of mine was editing an anthology of stories inspired by Ray Bradbury. The story “The Phone Call” was actually a story that I had written years before in kind of catharsis of my mother’s death. My mother died in 1988. So around 1989, when I was still dealing with that, I stayed up all night and I wrote the story called “A Phone Call,” which is similar to the story in this book. I wrote it in one draft. And then I lost it. And so for years I kept thinking about that story, trying to imagine it in different versions, as a novella or as a short film. I just never got around to it until my friend Sam Weller solicited a story from me for his anthology. And he told me, “You know, I’ve already got Margaret Atwood and all these other big names like Dave Eggers. All these people are committed.” And I’m like, “Oh, absolutely!”

Probably around 2011, a friend of mine was editing an anthology of stories inspired by Ray Bradbury. The story “The Phone Call” was actually a story that I had written years before in kind of catharsis of my mother’s death. My mother died in 1988. So around 1989, when I was still dealing with that, I stayed up all night and I wrote the story called “A Phone Call,” which is similar to the story in this book. I wrote it in one draft. And then I lost it. And so for years I kept thinking about that story, trying to imagine it in different versions, as a novella or as a short film. I just never got around to it until my friend Sam Weller solicited a story from me for his anthology. And he told me, “You know, I’ve already got Margaret Atwood and all these other big names like Dave Eggers. All these people are committed.” And I’m like, “Oh, absolutely!”

And then I thought about it. I thought, well, I don’t know. I’ve never really written that kind of story before. And then I remembered that I had written that kind of story, but I had lost it.

That’s what writing that story did for me. It tapped into those kinds of writers who I loved when I first began writing. So, Ray Bradbury, Ursula K. Le Guin—those sorts of writers I was reading when I was in grade school. Those were the writers who were at the forefront of my creative process when I would try to write creatively in grade school and high school.

And I think, at that particular period when Sam asked me to contribute to the anthology, I was just burnt out. I was burnt out on writing the kinds of stories that I typically wrote. So it was refreshing. And then that led me into thinking about other kinds of stories to write. But I didn’t want to write just in the mode of Ray Bradbury for the rest of the collection. Still, writing “The Phone Call” gave me license to do things that I hadn’t done before, to tap into those kinds of writers that got me interested in writing in the first place.

A side note: after I finished writing the story, and after I sent it to Sam, and maybe even after his anthology came out, when I was moving to Louisiana, I found the draft of that original story I’d lost in 1989. It was from one of those dot matrix printers. And, surprisingly, it was pretty similar, even though I hadn’t seen it since the night I wrote it.

I love that story. That’s fantastic.

I love that story. That’s fantastic.

I think this is one of the reasons the book works so well: the way you’re playing with all the different genres is energetic and unexpected. Similarly, you start the book in the first-person-plural POV. That really struck me, because I just finished reading Sharon Harrigan’s Half, which is a whole beautiful novel told in first-person plural. Since reading it, I’ve really been interested in the possibilities of different points of view, and you have several in this book.

Most of my early stories were first person and most of what I write now is limited third-person, so with this book I just wanted to try different things.

Even with the story, “The Creeping End,” which begins with that hardboiled detective voice, I wanted to have three different tones. The story is a triptych. In the beginning, it was three different stories that weren’t working. I just kept alternating between them. And then I thought, “These are all kind of the same character. It’s just that the tone is completely different.” And so then the challenge was to make a cohesive story out of three completely different tones, using the same character as the main narrator.

There’s an illusion in that, it’s like a point of view shift that doesn’t actually happen. It’s a lingering story.

In fact, this book is filled with not just that lingering, emotional resonance we mean when we call a story “haunting,” but it’s also as if the stories themselves are haunted (despite their being no actual ghost stories in the collection). The characters themselves either feel haunted or act almost as living ghosts (I’m thinking of the story “Catch and Release,” which centers around the reappearance of a woman who’d gone missing as a girl).

Do you think there’s a connection between these haunted characters and the way the stories linger for a reader?

You may remember me talking about this in class, that idea of what’s at stake for you when you write (what’s at stake for the writer). Often you don’t necessarily know what’s at stake. But I feel like if you burrow into the consciousness of the narrator deeply enough, you’re tapping into your own unconscious mind. And so maybe, by the time the book comes out, you can figure it out, you know, become your own analyst.

It wasn’t until I was completing the final revisions on the collection that I became aware that the book had these metaphorical ghosts, and I didn’t know why. I mean, I had a lot of things happen all at once. The end of a twenty-year relationship, the death of my father, moving 900 miles away from a place I’d been living for the previous twelve years. So there was a lot of this, this kind of lingering, or I guess a tangible absence like the characters in these stories all feel, but that I personally—you know, I’m very much the kind of person who’s like, “Okay, we just move on, we just trudge on to the next thing, the next tragedy in our lives.”

So channeling through the stories, I think, are those things that probably in some ways I was repressing, but doing it metaphorically. That’s why I like writing fiction. It’s so complicated, psychologically. In terms of how a story comes into being, it’s this mysterious process that you think you understand, but that you don’t until years later.

I don’t read my own stories over and over and over as a group, as a collection. I read them individually as I’m revising. But once it gets to a certain point and you’re going through the stages of copy editing, it’s like you’re just reading the book until you’re sick of it. And then that’s when you begin noticing these other weird patterns, where it’s like, “Oh, my God, I’m revealing way too much about myself.”

One of the things you’re talking about here is time. Something I know about you is that you are willing to let a story sit, to give yourself time to work it out. Are these all stories that had to sit for a while?

I work in a real piecemeal fashion. On the one hand, there are some stories where I’ll write an entire draft that I then put away for several years, and then come back to look at it to see if it makes sense. In some cases, I just hold on to an idea that I know that I’ll probably write about, but I don’t have the right form or the right way to tell the story yet.

I work in a real piecemeal fashion. On the one hand, there are some stories where I’ll write an entire draft that I then put away for several years, and then come back to look at it to see if it makes sense. In some cases, I just hold on to an idea that I know that I’ll probably write about, but I don’t have the right form or the right way to tell the story yet.

The story “The Lawyer” is an example. I once had a conversation with a lawyer under similar circumstances as the character in the story, and I would say with the exception of the very end of his monologue, the story in the book is pretty verbatim. As I sat there and listened to him and his crazy monologue spiral out, I was thinking, “This is the craziest shit I’ve ever heard.”

At the time, I guess I did think it was fodder for anything. But eventually when I did sit down to try to write the story, it just wasn’t working. It didn’t work until I changed the gender of the narrator. And that suddenly heightened the sense of danger because of the kinds of things the lawyer was rambling on about.

There’s a moment in that story where the predatory feeling is so overwhelming, I wanted to yell at the young woman in it, “RUN!”

Thinking about “The Lawyer,” the character’s jobs are central to many of these stories. Can you talk about the importance of work in stories?

Having grown up in a blue-collar neighborhood, I didn’t know anybody who didn’t work. And I also didn’t know anybody who wasn’t having money problems. So even in the case of the story “Catch and Release,” where it’s a young professor, the characters still have to earn an income, you know? There’s still money. But there’s also a sense of being trapped in something that you don’t like. In his book Working, Studs Terkel said, “This book, being about work, is, by its very nature, about violence to the spirit.” And I feel like that’s true in almost whatever job you have, the story of work is the story of misery. It is hard for me to imagine characters separated from work. So even if it’s children who I write about, the parents work. The kids are at school. These are real humans who have to buy food.

I’ve read those stories where I don’t know what anybody’s doing. And I just think, “Does everybody have a trust fund? I don’t know how they’re making their money.” It’s important because it informs who they are, what their interests are, whether they’re trapped in their jobs, whether they’re happy in their jobs, which, again, is not most experiences I’ve encountered.

Which brings us to the fact that gone are the days where writers can just write. We’re working. You work. You teach. How do you balance that? What advice do you have for people who are living the Studs Terkel life of misery and work, but who are also, artist-writers.

How do we do that? How do we feed ourselves and create art? You are prolific, how do you do it?

I mean I’m extremely lucky right now because I don’t have the workload that I used to have, but certainly for much of my life it was 4/4 teaching loads or working three jobs: a full time job, nighttime teaching, and temp work on the weekends. So throughout my life, trying to find time has always been the primary issue in terms of being able to have a writer’s life of some kind.

But during those years when I didn’t have time, it was important for me, and I think important for my sanity to try to at least—even if it was just for an hour a day, or even if it was for half an hour a day—to try to have some consistent writing time. That period when I was working three jobs, the first was probably like 8:00 to 4:00 and then I would walk home and then drive thirty miles to the community college and teach. And so I was waking up at four in the morning to write. Just so I could put a little bit of time in. So for me, it’s about having consistency.

But during those years when I didn’t have time, it was important for me, and I think important for my sanity to try to at least—even if it was just for an hour a day, or even if it was for half an hour a day—to try to have some consistent writing time. That period when I was working three jobs, the first was probably like 8:00 to 4:00 and then I would walk home and then drive thirty miles to the community college and teach. And so I was waking up at four in the morning to write. Just so I could put a little bit of time in. So for me, it’s about having consistency.

Times when I’ve let that go are times when I’ve been least happy. I started thinking, “Why am I doing any of this stuff?” Because certainly when I was working three jobs, none of those jobs gave me pleasure.

So even though I don’t think anything that I wrote during that period even got published, it kept me in the game. You know, if I want to play sports, if I want to be a basketball player, I still need to go out to the court every day and practice. When you say that I’m prolific, I never think of myself that way because I really don’t spend all day writing for the most part. But I do write almost every day. It just adds up.