Jeffrey Rotter / photo by Margaret McCartney

Let’s just get it out in the open now: the title of Jeffrey Rotter’s first novel, The Unknown Knowns, is an allusion to that Donald Rumsfeld speech

of linguistic loop-de-loops that would have driven George Orwell crazy. The book, which looks askance at our modern take on “Us vs. Them,” tackles the ontological questions presented by our vague and shadowy paranoia, but ups the ante considerably beyond the present moment in history to the personal crises that drive all good stories.

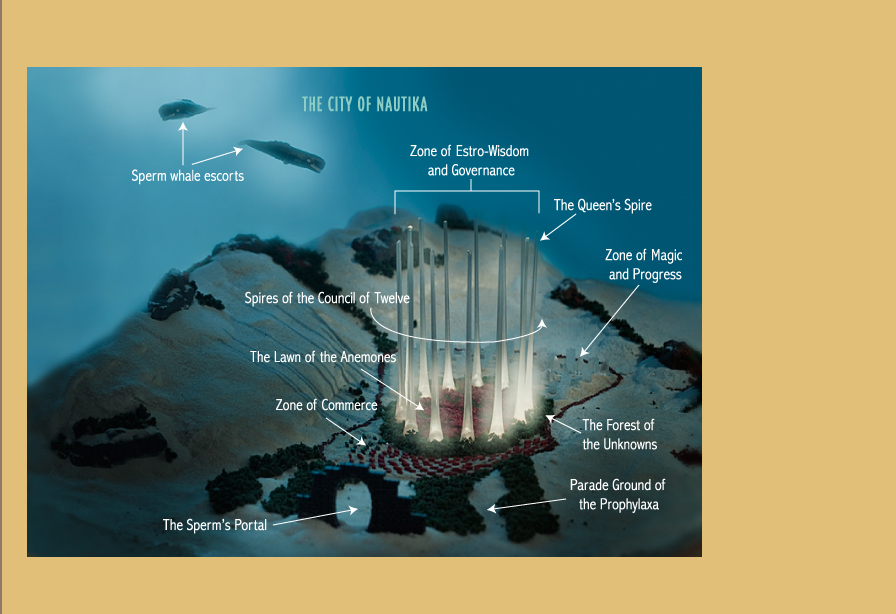

Jim Rath is a diorama builder by trade, comic-book fanatic by heritage, and a manchild by way of emotional maturity. As the novel opens, Rath has all but ruined his marriage to his long-suffering wife, Jean, with his fixation on Nautika, an underwater matriarchal paradise of aquatic apes, or Nautikons, that he believes evolved in parallel to humans. Rath’s foil is federal agent Les Diaz, who is on a mission from the Department of Homeland Security to protect the swimming pools and water parks of America from terrorist attacks. Through Rath and Diaz’s intersecting paths, Rotter presents the reader with a viscerally disturbing dilemma: can we trust ourselves? By turns darkly funny and chilling, The Unknown Knowns also contains marvelous passages that capture Jim Rath’s flights of Nautika-inspired fancy, which are so sincere and overblown it’s hard not to like the guy, in spite of his self-navigated path toward destruction.

Jeffrey Rotter’s writing has appeared in numerous publications, including McSweeney’s, the New York Times, and Spin, and he received his MFA in fiction from Hunter College. Here, the South Carolina native discusses the social risks of homemade clothing, museums as metaphors, the parallels between As I Lay Dying and reality T.V., and the ways in which imagination can change the world – for good and evil.

Interview

LEE THOMAS: Your book opens with a voice – Jim Rath – painting a vivid portrait of a remarkably difficult thing to describe: water. So convincing is his voice from that moment forward, it’s difficult to know which part of Rath’s perception is reality and which parts are tied to his fantasies of the underwater kingdom of Nautika. This is a book that subverts flights of imagination, but also succumbs – sometimes gleefully – to them. What about imagination interested you?

JEFFREY ROTTER: I think all writers have an ambivalent relationship with imagination. We owe everything to this mental asset. But it’s also the thing that got us beat up when we were kids. I remember making my own shirt and wearing it to class at my new school in 6th grade. This was at the height of preppydom. It was possibly the dumbest act of public creativity I’ve ever undertaken and I was justly mocked for it. Imagination ruined me for society, but it also made my life meaningful.

I recently read an article about the neuroscience of imagination. The claim is that huge imaginative leaps occur because the brain periodically breaks down and fires off random cascades of neurons. The author compared it to a collapsing pile of sand, which I think is really poetic and feels exactly right. So in some ways imagination is a systemic failure—a controlled failure, but a failure nonetheless. I like that idea.

Also I find it pretty silly that a greater value is placed on “dirty realism” than on more “speculative” fiction. This is, of course, a fairly recent phenomenon, and it’s part of the same trend that motivates reality TV. But just as Fat Camp is no more real than a sitcom, so literary realism is no more genuine than well-made fantasy. Empathy for a character requires a leap from reality no matter whether she’s an Idaho housewife or a molecule. Both require that the writer embrace an alien reality to make the reader feel something. I can get as choked up reading Cosmicomics as I can Housekeeping. In The Unknown Knowns I enjoyed blending political fictions—which we’re supposed to accept as fact—with the unabashed make-believe of Jim Rath’s undersea civilization. In the end there isn’t much difference.

You put the reader in the position of arbiter between multiple unreliable witnesses. The story is very rooted in the government’s maneuvers post-9/11, but the question at the heart of The Unknown Knowns seems much more basic than “Can we trust our government?” It’s more: “Can we trust ourselves?” That’s a sticky question for the novelist.

I don’t think of this as a political novel. I’m not politically astute enough for that. You’re right; it’s about larger questions of trust. And, of course, we can’t trust ourselves, but we don’t have much choice. Jim Rath is a diorama builder by trade. In a rare moment of reflection close to the end of the novel, he compares the world to a museum. Each of us builds his or her own museum of the world that filters out the noise from what we value most. So Jim’s world is a Museum of the Aquatic Ape, and every artifact relates to that. Similarly, Diaz lives in a museum of jihad, in which every gesture is a threat and every institution a point of entry for terror.

The Unknown Knowns is, in part, about competing misapprehensions of reality. Our visions of the world—as crazy as they are—become unreliable only when they cross paths with someone else’s. That’s when the instability begins, and that’s where fiction thrives.

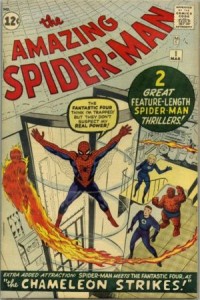

In an interview with the Columbia, SC Free-Press, you said you wanted Jim Rath “to have the brain of Stan Lee, the spirit of Elaine Morgan, and the poetic voice of Kenneth Koch.” Since you mention Lee, I assume you are, to some extent, a Marvel man. What other comic books or graphic novels have influenced you?

During my formative nerd years, the 1970s, Marvel had the weirdest titles. DC represented the post-war sensibility. Superman was impervious to almost everything; he was the ultimate immigrant who made good; he was upbeat and so American. Marvel’s heroes represented the fallout from the fifties and sixties. The Fantastic Four were victims of the space race. Spider-Man was poisoned by radiation.

I can’t say I’ve continued to follow comics in my adulthood, and I haven’t read enough graphic novels to speak intelligently about them. But the idea of superhero as victim of society resonates with me. Jim Rath is that kind of superhero, without any of the super aspects.

There are the two obvious central characters – Rath and Diaz – but there is also a third: Jim’s wife, Jean. Rath and Diaz fall victim to their own fantasy worlds, but Jean is an actual casualty of someone else’s delusions. In some ways it feels like a gross failure of imagination. Do you think the current climate – political or social – feeds this kind of lack-of-empathy-until-it’s-too-late? What role does fiction play in the landscape?

The collateral havoc these two delusional guys wreak is pretty awful. People are injured. Jim’s wife is abandoned. A lot of the actual pain is in the periphery, because Rath and Diaz manage to mask theirs with fantasy. Jean doesn’t have that option. She lacks the imagination and she becomes a victim of someone else’s. I hope readers feel her loss.

I don’t think there’s anything new about our lack of empathy. That our president is mocked because he values empathy in a Supreme Court justice is pretty disturbing. And I think there is a Conservative ethos that encourages self-importance; you see it all over pop culture, from first-person-shooter videogames to Twitter to the health-care debate. But I suspect people aren’t any more solipsistic than they’ve always been. We’re pack animals who are trying desperately to pretend we’re fancier than that.

What role does fiction play in all this? Judging by book sales, a pretty diminished one. But I do think if fiction has a moral value, it’s about helping readers understand what it’s like to be someone else. To let them inside someone else’s museum.

The tradition of the road trip, the odyssey, the idea of leaving home, looms large in American literature. In As I Lay Dying, Faulkner made certain there was no going home again for any of the Bundrens. Travel itself played a role in changing character. Jim Rath’s road trip feels a bit like a crazed, once-noble general blazing through battles as he fights a war that has already been lost. Are there “travel novels” that you admire? Do you think there’s something about the idea of setting forth that appeals to American writers particularly?

The tradition of the road trip, the odyssey, the idea of leaving home, looms large in American literature. In As I Lay Dying, Faulkner made certain there was no going home again for any of the Bundrens. Travel itself played a role in changing character. Jim Rath’s road trip feels a bit like a crazed, once-noble general blazing through battles as he fights a war that has already been lost. Are there “travel novels” that you admire? Do you think there’s something about the idea of setting forth that appeals to American writers particularly?

If I were a cynical person, I’d say that travel is simply a device for ordering a novel. A writer can manage plot points and the tension between them as if they were destinations on a map and the interstates between.

I’m really happy you mentioned As I Lay Dying. It’s one of my favorite books (although I prefer Absalom! Absalom!). I agree that the Bundrens can’t return home, but for all the trials and mental anguish they suffer, it’s also a classic American round-trip. Anse picks up his false teeth and a new lady, and they drive home. Everything changes but nothing does. In that sense it feels very American, in a reality-television way—the whole concept of epiphany is so cheapened that it becomes a punch line.

When I started writing The Unknown Knowns I’d just finished reading Don Quixote (I faked my way through it in college). While I can’t say I enjoyed the book, it certainly made an impact. These days you can’t write a novel without explaining to death a character’s psychology, but Cervantes doesn’t bother with motives. Quixote is on two lousy road trips—psychological and physical—but by the time we meet him, the mental ship has already sailed. He’s nuts from page one. Don Quixote’s psychological journey has already played out in other novels, in all those romances that he now takes for reality.

When I started writing The Unknown Knowns I’d just finished reading Don Quixote (I faked my way through it in college). While I can’t say I enjoyed the book, it certainly made an impact. These days you can’t write a novel without explaining to death a character’s psychology, but Cervantes doesn’t bother with motives. Quixote is on two lousy road trips—psychological and physical—but by the time we meet him, the mental ship has already sailed. He’s nuts from page one. Don Quixote’s psychological journey has already played out in other novels, in all those romances that he now takes for reality.

Likewise, Jim Rath’s delusions are rooted in other books, 70s comics and Elaine Morgan’s aquatic ape titles. As a contemporary reader with a pretty limited experience of Wolfram von Eschenbach or whatever Don Quixote was supposed to have read, I find the source of his madness kind of perplexing. That’s why I interspersed Jim Rath’s story with scenes from the imagined world that motivates his stupid behavior.

Keeping with the idea of travel: The physical elements of the journey – hotel rooms, bad food, indoor pools – are key to creating a mood, a place and a psychic space for Rath and Diaz to interact: they’re displaced from reality and also from a rooted daily existence. What is the relationship between their displacement and their insatiable need to keep moving, especially since there is something oddly static about checking into a motel room night after night?

Yeah, I like the idea of travel without any real movement. That’s what vacation has become. We go halfway across the country to stay in a hotel that’s a perfect clone of the one down the street. Only the theme of the cheeseburger changes. It’s pretty trite to say, but all these chain stores and hotels and churches do reinforce a feeling of dislocation. And when you’re dislocated any old delusion can start to feel like an acceptable reality. Why do you think people do such freaky shit in malls and government offices? I think that’s what happens to Jim Rath and Les Diaz. For different reasons they lose a sense of America as a concrete place, so they substitute it with a fantasy world. And the fantasy world comes back to bite them.

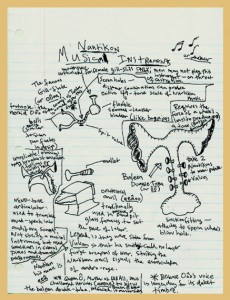

Talk to me about the cool pages from Jim Rath’s notebook on the Museum of the Aquatic Ape website. Artist’s renditions?

from Jim Rath's notebook

No, they aren’t artist’s renditions. The pages from the notebooks are my half-assed attempt to draw something in a Jim Rathian style. I do make drawings, though. Mostly maps. Peter Carey, the director of the MFA program at Hunter, taught us all to sketch whatever physical space we intend to describe, so I drew fairly detailed maps of the waterpark and Nautika. The practice is incredibly helpful for spatially brain-dead people, which describes most writers I know. It’s also useful when your characters need to find the bathroom, or a visitor to an undersea city needs to know where to penetrate the plasmalike walls of an ontogenic spire.

So, what are you working on at the moment?

Thanks for asking. I’m working on a mini comic about Jim Rath’s further adventures in the aquatic city of Nautika. My wife, Margaret McCartney, is a really talented illustrator and textile designer. She’s doing all the drawings. I’m also finishing the manuscript of a new novel, about phantom islands, alligator capture, a ghost, and a boy who can’t grow up.

Atlas of Nautika / courtesy of the Museum of the Aquatic Ape

Further Resources

– Read an excerpt from The Unknown Knowns, and consider buying your copy from a local indie bookseller.

– Visit the website of the The Museum of the Aquatic Ape for a diorama tour of Nautika, Jim Rath’s notebook sketches, and more.

– Watch Elaine Morgan expound her theory that humankind evolved from aquatic apes at the 2009 TED conference.

– Read further about the neuroscience of imagination in David Robson’s article “Disorderly Genius: How chaos drives the brain.”

– Make a playlist of Jeffrey Rotter’s “favorite anti-government philippics”.