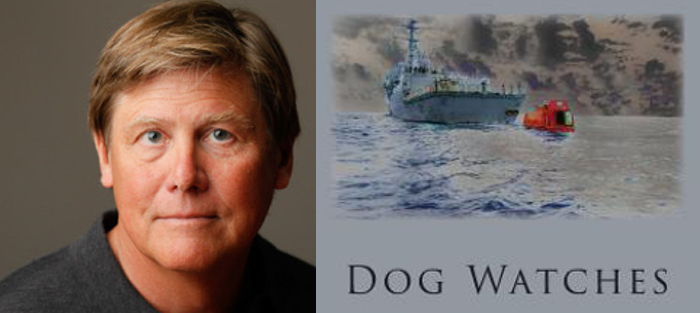

To say that Rolf Yngve has taken an unusual path to his first book would be an understatement. Yngve first took up fiction as an enlisted man in the U.S. Navy in the 1970s, and marshaled his talents enough to end up in Best American Short Stories in 1979. Then fiction slipped out of his life as he worked his way up to Captain, only to force its way back onto his radar.

The stories in Yngve’s debut collection, Dog Watches (Saddle Road Press), feature characters locked in battle with forces they can’t control or understand. One expects death to be close at hand in a combat story full of enemy guns blazing; but in Yngve’s work, it’s still there in the shadows even while the ships he writes about are (at least ostensibly) at peace.

Physical death can come from a small boat launching rocket-propelled grenades, from a carless move in a storm, from a mistaken wandering in the bowels of a ship, or from the fed-up tiredness of a self that doesn’t know its purpose on earth. Psychic death can come from lying, from telling too much truth, from holding onto unprocessed memories, from reliving guilt too many times.

One way or another, that grim truth is never far away when you’re on a warship at sea, and this imbues Yngve’s prose with a haunted whisper of omnipresent danger that makes Dog Watches such a strong collection. Behind the veil of military uniformity sit forces of destruction and self-destruction, and Yngve’s hand is always on that veil, pulling it back for us to take a look.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: I’m very curious about the time between your early foray into fiction in the late 70’s and the writing you’ve done since you retired from the Navy. Did you keep your writing practice going while you were working your way up in command, or did it sit dormant? Did some changes to your writerly self—unseen, internal developments or reconfigurations—happen during that time?

Rolf Yngve: Not dormant, but not moving either. And it wasn’t so much the Navy that made me stop going forward. I worked on the fiction pretty steadily until the mid 1980’s. Then a strange thing happened: a wonderful, early marriage to a passionate reader and writer ended, and I found myself unable to read fiction or poetry of any kind. I even remember that last novel, still only halfway finished, a splendid Richard Bausch title, The Last Good Time.

I still wrote. But—this is true—trying to write fiction without reading fiction is like drinking without water. All the work from those days shows the lack of reading, the lack of thinking like a writer. I still have boxes of failed manuscripts lying around in a closet like sedimentary rock.

By the mid-1990’s, I had found another family, married another great reader, and the sound of it all started to come back when a former teacher, David Kranes, took a look at some of my work and encouraged me to start thinking like a writer again. Forward another decade, and the stories of Dog Watches began to come, along with a couple of failed novels, a few memoir pieces, and another clutch of stories less fertilized by the Navy experience. But I had started to read again. Everything.

I’m not sure I answered your question. I always wrote, but I wasn’t paying attention to writing. The writing I do is something that comes out of reading, and especially close reading, wanting to emulate people like William Trevor, or Stephen Crane, or Antonya Nelson, or Tim O’Brien, or Joyce Carol Oates, or Ray Carver. Without those whispers in my ear, I was dry.

The stories in Dog Watches are based on real life experience, yet you also write nonfiction about your Navy time. What is it about a particular experience that makes you fictionalize it rather than write about it in nonfiction—and vice versa?

My impulse, my desire is fiction. All of my fiction comes from the confabulator’s pleasure. Telling a story of any kind, I feel a demand for a voice, or a point of view, or an event larger than the real event. One of my earliest memories was a dressing down for announcing to my first-grade class that my father was a paleontologist. Father—an attorney—was not pleased. Even today, especially when I have too much to drink, I find myself spinning down that rabbit hole of a story too good to be left alone.

My impulse, my desire is fiction. All of my fiction comes from the confabulator’s pleasure. Telling a story of any kind, I feel a demand for a voice, or a point of view, or an event larger than the real event. One of my earliest memories was a dressing down for announcing to my first-grade class that my father was a paleontologist. Father—an attorney—was not pleased. Even today, especially when I have too much to drink, I find myself spinning down that rabbit hole of a story too good to be left alone.

I find it hard to tell fact. I recently finished a book-length memoir centered on the murder of an officer thirty years ago. And what I discovered as I came into the book was that nearly every “memory” I had about my friend’s death, and most of my memory of the events in 1986, were not only flawed but often completely wrong, expanded by my imagination and liar’s instinct to be bigger than it had been. I had to seek out the lies I had been telling myself to find the true story. And that search has become part of the book itself.

Here’s what I learned from working on that book: I hide behind fiction. Fiction is my curtain and my one-way mirror where I can see out, and no one can see in. Or so I hope.

Yet because much of your fiction is autobiographical, how do balance the real and the invented? Specifically, how is the work transformed so that it has its own life and isn’t tied exclusively to your autobiographical memory anymore?

Mirrors again. Every story wants to invade the other side of the mirror. It wants to expose me as the author. And I feel the impulse to sell an acceptable version of myself. It’s a form of narcissism, isn’t it, that sense of self-protection?

But my work dies when I am trapped inside that self-image I want to protect. The keys to freeing myself are the old tricks of point of view and distance. The events in “Personal Effects” were quite real, but they occurred on separate ships. I did inventory a locker with a chief who told me to read the dead sailor’s letters. I had thought for years I would write a story about that inventory, then gave it up because Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried” had pretty much snuffed the life out of that narrative line for anyone who came after him.

But I had also reported to a ship in a dry dock in Brooklyn, and once I did indeed find a packet of letters—not from a dead man—in a locked safe. To go beyond O’Brien’s story and to go beyond myself, I combined those three separate events. And to tell about them, I had to find both distance and intimacy to explore the self-involvement of the story’s young protagonist.

And, you know, maybe that protagonist was me. Maybe I was as self-involved and as irresponsible as that young character I created. And perhaps the distance I’m talking about is the literal distance of time. All the real events happened long ago. But it is certainly also the distance of a dispassionate omniscience, the meta-persona borrowed again from O’Brien, one who could deliver that story as an observer, a member of the club. A Marlowe borrowed from Conrad.

There’s so much Navy detail in this collection—terminology, acronyms, leadership hierarchy—yet nothing felt out of my league to understand. After a short time, an XO [an Executive Officer] simply became an XO, and I didn’t try to “translate” the terminology back into civilian-speak. Did you need to work to find this balance, and if so what did you do?

You can’t imagine how much I’ve tried to achieve something like that in my work. In fact, one could say I spent the two years in the Warren Wilson MFA program studying how to create clean linkages into an unknown world. I wanted, very much, to avoid the classic explicative section one finds in writing about science, war, crime, space, or the sea. Melville’s whaling chapters in Moby Dick come to mind.

At Warren Wilson I also had master teachers who helped me study masters. Sometimes genre fiction taught me. C.S. Forrester’s classic Navy novel, The Good Shepherd, brilliantly reveals the diurnal life of a ship through the people in it. Issac Babel’s Red Cavalry, Andrea Barrett’s work, especially Ship Fever and The Air We Breathe, James Jones’s Thin Red Line, much of Conrad—those come to mind as exemplars I studied. I looked at how Alice Munro and Joyce Oates use the familiar to take us into the psychological unknown. Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, and Robert Boswell’s Half Known World, showed me tendrils of connection to the readers’ imaginations. I wrote my thesis essay on the use of extra-textual reference to create context for a reader in Geoff Ryman’s extraordinary novel Was. And yes, also Melville. “Billy Budd” is thrilling in what it explicates through imagery and sense. All of them showed me how to bring an unknown world alive.

Isn’t it about respect for the reader? Somehow one must avoid pandering, avoid lectures, avoid objectification of the reader and the characters, avoid one’s self-promotion and, in the same breath, capture the verisimilitude—the sound—of expertise. Stephen Dobyns, a poet, taught me to use all the senses all the time and what I got from him, and other poets, was the notion that the actual “thing” of the story is less important than its meaning. Especially in short fiction, one has to determine what meaning, what thing, is absolutely required for the story. “None of them knew the color of the sky.” Crane’s first line from “The Open Boat” is a perfect example. Maybe every story I’ve ever written has come from that one line. If done well, and I don’t always do it well, this kind of writing resembles the sort of craft I associate with fine woodworking. Good joinery holds a structure together with beauty but never shows the effort and training it took to master. It must be seamless. The perfect joinery.

One of your characters, Hayden by name, talks about how he became “Hank” when he joined the Navy. It strikes me that many of your characters wear not only a physical uniform, but a psychological one as well. They’re in disguise, shaping their exterior selves to fit into a system that their interior selves can’t abide. How do you get that internal conflict on the page?

I think all honest, literary effort reflects the fact that we humans are imprisoned by our cultures. It isn’t so much getting the internal conflict onto the page; it is letting it come out.

As for technique, isn’t it all about point of view again? Isn’t the con game of fiction always about letting the reader believe she knows more than the character? Shouldn’t the reader be simultaneously engaged and distanced, confident and mystified? In the Hank story you mention, “Randy Root,” the choice of point of view sets up a judgment of Hank. And that judgement had to be seen through the eyes of a close third-person narrator. That’s how it gets on the page. I needed to get into the hard unknowns of my character’s ruined life. And I had to do it by creating a judge to lead us into his mind and heart through her questioning, her judgement. Her wonder.

Some of your stories take a while to find their depth, and then they explode—“depth charge” stories, if a landlubber can borrow a seaman’s term. For instance, “Billy,” which features a missing cat but is ultimately about something much darker. Do you go into such stories knowing the bottom will drop out, or do you find the bottom along the way and punch through it?

Both. It depends upon the story. “Billy” was written knowing the ending. I had been trying to get at a character who cannot find the courage to confess a terrible guilt, and I knew it had to be a depth charge, as you call it. Here’s the thing: I did not know what the reason for his guilt would be; it was the weight of unreconcilable guilt itself that intrigued me. But the ending, the depth charge, couldn’t be realized until waterboarding became a “thing” in our cultural sense, and it took the murder of my own cat (by a dog) to lead me into “Billy.” Something had to lead to that door my character wanted to open, but could not.

On the other hand, I had worked, again for years, on a story about a man confronting a young person about to jump from a bridge. I knew there was something in that story, but writing it in different voices, from different points of view, about different results… none of it worked. Then was in a workshop with Tim O’Brien, of all people, and he said, “Hey, what if…?” That led to the turn. His comment revealed what the story was all about—its depth charge. There I had to search for the turn until I found it.

At one point a naval captain observes that “Rage had always been a tool in the kitbag of leadership arts.” What happens on the personal level—to leaders and to those they lead—when rage gets relied on too much? What happens to nations?

Ok, we are way beyond fiction here. But it’s a great question. I think, maybe, people can answer that question for themselves if they ask themselves this: When you think of the moments when you were the object of rage, do you remember the reason first? Or do you remember the rage?

Feigned rage, when it’s a sort of performance—the way my XO starts out in “The Mouse”—can be considered a kind of motivator. It’s an infection that lights the fire of rage in others. And in some circumstances, like maybe a halftime ass-chewing in a football game, all those witnessing the performance know that the coach is acting out a sort of fake rage to get them charged up. And perhaps there is a short-term benefit. Perhaps that halftime rage will create a team that wins a losing game.

But what rage does most of all, feigned or real, is give license to rage. And after that ass-chewing, someone will run his or her head into the heads of other players hard enough to injure for life. They will kill themselves for the team. That’s what happens when a leader goes through that door into acts of rage. He pulls his followers with him to visit chaos and damage. Does that make a better football team, a better ship, a better nation?

I think that rage of any type, true or fake, encourages the abandonment of empathy for another’s pain. Not the lack of empathy. Not the inability to feel another’s pain. These are sicknesses. Rage charts a course that abandons empathy for a supposedly “greater good,” and that may be the great evil of humanity. Abandoning empathy out of rage or training or expediency or even habit. To paraphrase my character Hank, it is feeling the worm twist in your fingers when you bait a hook, but not caring.

Books by veterans have always had a significant place in American letters, and we’ve seen increasing awareness of the writing/military connection since 9/11. What purpose, in the big sociocultural picture, does writing about war and the military experience serve in our culture? And what do you hope that people in civilian life will take away from Dog Watches?

Books by veterans have always had a significant place in American letters, and we’ve seen increasing awareness of the writing/military connection since 9/11. What purpose, in the big sociocultural picture, does writing about war and the military experience serve in our culture? And what do you hope that people in civilian life will take away from Dog Watches?

I have to thank you, Steve, both for this interview and this question on Veteran’s Day. I met you at Bread Loaf in 2008, and I was simply astounded at how well I was treated there. I had been very concerned I would feel ostracized by a community I admired, a literary community I so much wanted to join. You and some others made me feel so welcome and, really, changed my life. I guess that goes back to your first question, why did I start up again? I was welcomed. I was encouraged. Community. I love that notion.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if writing about war created community? Wouldn’t it be perfect if somehow the stories in Dog Watches helped the civilian reader, any reader, see these characters as human? Not as working stiffs or servants to whom we owe thanks. Not as CGI-enhanced super humans. Not as victims sacrificed to suffer lives of unending psychic torture. Not as fearsome objects from an unknown world who are now “different.” Wouldn’t it be wonderful if such stories allowed anyone, including veterans, to see these people as real men and women who chose young adulthoods filled with all the pleasures, camaraderie, growth, and risks that come from participating in potent events with enormous consequences?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all veterans felt as accepted as I did a decade ago at Bread Loaf? That’s what I want, what I think all of us want: to be considered members of our society, our culture, our many communities. To be part of something larger than ourselves. To belong.