Richard Lange is the author of the novels Angel Baby (Mulholland Books, 2013) and This Wicked World (Little, Brown and Company, 2009), as well as the short story collection Dead Boys (Little, Brown and Company, 2007). Released earlier this year, Angel Baby is Lange’s best work yet, a pulsing, quick-paced literary crime novel that punches hard for three hundred pages. Lange turns what Richard Ford calls the “raw, unreconciled life” into the basis for an unrelenting chase story that features hardcase men and women caught somewhere between despair and redemption. Lange’s characters—to borrow a line from Deirdre Bair in her review of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable trilogy—let the “inner torments of their past life [. . .] sustain their present existence,” and they’re heartbreaking in their fierce desperation. The writing is tough and unsentimental, and Lange is a master of economy. Angel Baby is savage and sleek, a stripped-down vision of what it takes to escape the ruins of a broken life.

Lange received a degree in film from USC and worked in the magazine industry for years before turning to writing full-time. He was the 2008 recipient of the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a finalist for the 2008 William Saroyan International Prize for Writing. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2009. Most recently, Angel Baby was optioned by Warner Brothers.

I interviewed Lange by e-mail over the course of a few weeks.

Interview:

William Boyle: “Cinematic” is a word that’s been tossed around in the early blurbs and reviews of Angel Baby. I’m not sure I get it. It’s as if the movies invented great pacing. Do you write with that in mind, making something feel movie-like? Or do you find it troubling? Tied to that: what were your influences structurally? Did certain books (or films or TV shows) serve as models for what you did with the multiple POVs?

Richard Lange: I’m not sure about “cinematic” either. I was actually a bit insulted when I first saw it used to describe the book, feeling that it somehow diminished the work in some way, like, “Don’t worry, potential readers, it’s as easy to enjoy as sitting on your couch and watching a movie. No intellectual involvement required, we promise!” Maybe it has something to do with, as you say, the fast pace of the story, but lots of books move at a rapid clip. Maybe it’s the amount of action in the book, or the deliberately straightforward chase structure, neither of which are exclusively or particularly cinematic. The term first showed up in the publisher’s description of the book, which is always a confusing and vaguely unsettling mélange of buzzwords and ad-speak designed to simplify the work in order to sell it to the widest possible range of booksellers and readers. I assume its continued use is due to bored (or lazy) reviewers grabbing onto the concept and running with it in order to avoid doing too much original thinking. Deadlines, you know.

Whatever the reason, I sat down to write a book, not a blueprint for a film. If the book doesn’t stand on its own as a literary work, I’ve failed. The chase structure is a result of my desire to reduce the plot in this book to something elemental. In This Wicked World, my first novel, I ended up spending a lot of time wrenching the plot into shape, and this time I wanted to concentrate more on character, setting, and language. The multiple POVs gave me the opportunity to tell the story in a number of different voices and to get inside the heads of a variety of characters. It’s all about keeping me interested in the book during the long process of writing it. And if I’m excited and engaged and having fun, I think the reader will also enjoy it. I used multiple POVs in This Wicked World and some of my short stories too. It’s a device that helps me tell the stories the way I want to tell them. Is it cinematic? Once again, certainly not exclusively or particularly.

Whatever the reason, I sat down to write a book, not a blueprint for a film. If the book doesn’t stand on its own as a literary work, I’ve failed. The chase structure is a result of my desire to reduce the plot in this book to something elemental. In This Wicked World, my first novel, I ended up spending a lot of time wrenching the plot into shape, and this time I wanted to concentrate more on character, setting, and language. The multiple POVs gave me the opportunity to tell the story in a number of different voices and to get inside the heads of a variety of characters. It’s all about keeping me interested in the book during the long process of writing it. And if I’m excited and engaged and having fun, I think the reader will also enjoy it. I used multiple POVs in This Wicked World and some of my short stories too. It’s a device that helps me tell the stories the way I want to tell them. Is it cinematic? Once again, certainly not exclusively or particularly.

All that said, I’m a film nut, and have been all my life. My writing has been influenced by film as much as it’s been influenced by other books, and I probably know more about film history than literary history, which is only natural, as film was the dominant art of the 20th century. And if I discovered anything in cinema that I could steal to make my books better, I’d do it in a heartbeat.

Can you talk about how you created the novel’s characters—Luz, Jeronimo, Thacker, Malone, and El Principe? I really love that none of them are totally sympathetic and yet we feel sympathy for all of them (except El Principe). Where did they come from? Did you feel differently about them at the beginning than you did at the end?

Malone was the first character I came up with, and the impetus for the book. I read an article in the L.A. Times a number of years ago about a dissolute white guy who drove illegals across the border for a Mexican pollero and thought, I’m going to write about a dude like that someday. When it was time to do a second novel, and I sat down and started sketching out the story, that’s when Luz, Jeronimo, and all the others came along. I’m not a big planner when I write, so they were all born, one by one, as the story developed. I fleshed them out, gave them back stories, and set them loose in the world of the book.

The truth is, it’s not that difficult to create compelling characters if you’re pulling them from your own experiences and filling them with your thoughts and feelings. It’s kind of like being a method actor, I guess. Somebody once told me that everyone in any of your dreams is essentially you because your mind has created them. That’s how I feel about all the characters in my work. Consequently, I’m always hurt when someone says they hate this character or that character, because what they’re saying is they hate some aspect of me.

The truth is, it’s not that difficult to create compelling characters if you’re pulling them from your own experiences and filling them with your thoughts and feelings. It’s kind of like being a method actor, I guess. Somebody once told me that everyone in any of your dreams is essentially you because your mind has created them. That’s how I feel about all the characters in my work. Consequently, I’m always hurt when someone says they hate this character or that character, because what they’re saying is they hate some aspect of me.

Much of the novel takes place south of Los Angeles in Tijuana and Tecate and at the penitentiary. I know that you know L.A. inside out. Did you know the other places well enough to simply set the action there or did you scout locations? What kind of influence did place have on how you made the characters?

I’ve been going to Tijuana since I was a kid, so I know parts of the city pretty well, how it smells, how it sounds, how it feels. I’ve hiked a lot in the scrubland just north of the border, so that landscape was familiar to me too. I made special research trips to Tecate, Imperial Beach, and Compton to pick up details I could use.

Well, I call it research, but it’s not like I’m taking notes. I have a few beers, walk the streets, eat a few meals, see the sights. I stayed in the hotel Luz and Malone stay in in Tecate, went to those bars, went to the cemetery in Compton, and walked the pier in Imperial Beach. The only place I didn’t visit firsthand was La Mesa prison, but you’d be surprised what you can find on YouTube. There were videos shot by a Christian group that ministers to the prisoners there, and it showed me what clothes the convicts wear, how they look, and gave me a glimpse inside the prison itself, enough to allow me to imagine the rest of it.

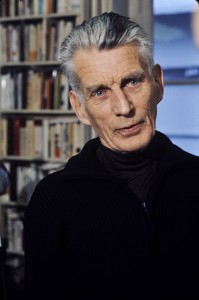

You recently wrote about Samuel Beckett in an essay on literary last moments for the Mulholland Books website, saying, “[There] is something so profoundly sad, hopeless, and hatefully true in [his] meditations on loneliness, regret, and death. I believe in a universal melancholy, and Beckett has come closest to getting it down on paper.” How did he influence what you did with language and tone in Angel Baby?

Beckett is one of the big influences on everything I do. You read him, and you’re forever changed. The psychological bleakness he captures, the air of regret. But there are a thousand other influences at work in Angel Baby, too. Writers, musicians, filmmakers, painters. My work is an amalgam of all of them plus my own experiences, all tossed into a blender, then formed, battered, breaded, and fried. Melville, Zola, Hemingway, Carver, Mamet, Denis Johnson. Cormac McCarthy, Robert Stone, Taxi Driver, Badlands, Bonnie and Clyde, Dancer in the Dark, Tom Waits, Black Flag, Will Oldham, some guy I overhead at a Laundromat once, the desert in a certain light, the feel of the sun on the back of your neck when you’re miles from water. Every time I sit down to write, all that and more is there, and I write best when I give myself up to the maelstrom and stop trying to control things, when I trust my natural rhythms. That’s not to say that it’s easy or that great stuff just pours out of me. I work hard to find the right word, the right cadence, the right moments in a story to spotlight, but it starts with letting go, not bearing down.

Beckett is one of the big influences on everything I do. You read him, and you’re forever changed. The psychological bleakness he captures, the air of regret. But there are a thousand other influences at work in Angel Baby, too. Writers, musicians, filmmakers, painters. My work is an amalgam of all of them plus my own experiences, all tossed into a blender, then formed, battered, breaded, and fried. Melville, Zola, Hemingway, Carver, Mamet, Denis Johnson. Cormac McCarthy, Robert Stone, Taxi Driver, Badlands, Bonnie and Clyde, Dancer in the Dark, Tom Waits, Black Flag, Will Oldham, some guy I overhead at a Laundromat once, the desert in a certain light, the feel of the sun on the back of your neck when you’re miles from water. Every time I sit down to write, all that and more is there, and I write best when I give myself up to the maelstrom and stop trying to control things, when I trust my natural rhythms. That’s not to say that it’s easy or that great stuff just pours out of me. I work hard to find the right word, the right cadence, the right moments in a story to spotlight, but it starts with letting go, not bearing down.

Since we last talked, Warner Brothers optioned Angel Baby and brought you on as screenwriter. Can you talk a bit about what the process of adapting your own work has been like so far? Also, can you talk about your hopes and fears re: the movie? How does being a film nut play into it?

I haven’t started working on the screenplay yet because it takes forever for the lawyers to hammer out the final contract. I had a meeting with the people at Warner Bros., though, and they were so nice it scared me. They seem to be willing to let me write the first draft the way I want, with no serious input. Maybe later they’ll step in and start remaking the story into something else. Or maybe not. I have no clue how this stuff works, so I’m taking it step by step. The film will be different from the book in some ways because I don’t want a lot of back story slowing things down. I want it to move quickly when it needs to but also to have quieter “character” moments. I suppose a lot of the feel of the film will be dependent on the director, whoever that ends up being. I’m just excited to be included in the process. Just driving onto the lot was a big thrill for me. I understand, of course, that the chances of the movie actually being made are slim — there are hundreds of projects being developed out there, and very few reach the screen — but I’m going to enjoy the ride while it lasts. I also got a blind script deal for a pilot with Warner Horizon TV, so it looks like I’ll be mucking around Hollywood for a couple years at least. They’ll probably break my heart, suck me dry, and leave me shivering naked on the side of the freeway, but I should get some good stories out of it and a couple of good paychecks.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on Richard Lange and his work, please visit the author’s website.

- Read Lange’s blog post about “literary last moments” at the Mulholland Books website.

- Check out the L.A. Times write-up on Angel Baby, a “beautifully paced, deftly written book.”

- And be sure to read William Boyle’s review of Angel Baby in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

- Find Richard’s story “The Hero Shot” at FiveChapters.com.

Contributor:

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, NY and currently lives in Oxford, MS. His first novel, Gravesend, is forthcoming from Broken River Books. His writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Salon, L.A. Review of Books, Hobart, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and other magazines and journals.

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, NY and currently lives in Oxford, MS. His first novel, Gravesend, is forthcoming from Broken River Books. His writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Salon, L.A. Review of Books, Hobart, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and other magazines and journals.