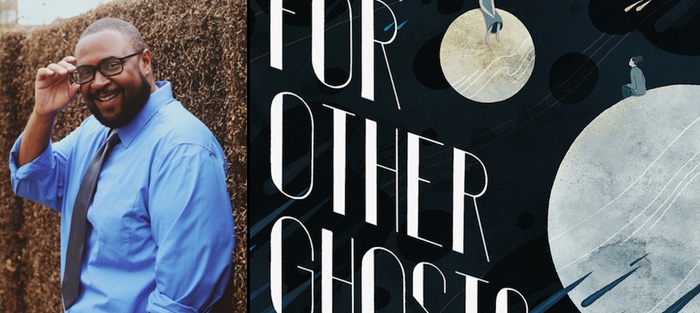

I first met Donald Quist at Vermont College of Fine Arts. VCFA is a small campus, so it wasn’t long before our paths crossed while we studied for our MFAs in writing, and what always impressed me about Donald was his ability to be a constant source for inspiration to those around him—helping others and offering perspective on writing and life—while also somehow finding the time to craft sharp, introspective short stories of his own. I enjoyed his company and work so much that, about a year after graduation, when I took over managing duties at the online journal Atlas and Alice Literary Magazine, I asked Donald to come aboard as a fiction editor. We worked together on the journal for three years and nine issues, and the experience only reinforced to me Donald’s strong critical eye, not to mention his commitment to aiding emerging authors.

In October, Awst Press will release Donald’s new story collection, For Other Ghosts. The twelve tales within are quintessential Quist: focusing on the lives of people in crisis from all over the world. Donald writes with an unwavering pen, unafraid to place his characters in dangerous situations that test their humanity. Whether they’re being held at gunpoint by a corrupt soldier or sharing drinks with a lecherous professor, the consequences of each character’s action create ripples that Quist confidently shows to his reader, as if to say, “Is this the way we should live? Is there a better way to love yourself?”

Besides For Other Ghosts, Quist is the author of the essay collection Harbors (Awst Press), the 2016 Foreword INDIES Bronze winner and a finalist for the 2017 International Book Awards, and the crowd-funded story collection Let Me Make You a Sandwich (2010). The stories in For Other Ghosts first appeared in Puerto del Sol, Cleaver Magazine, Storychord, Hunger Mountain, and other publications.

Donald Quist holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and has received fellowships from the Sundress Academy for the Arts and Kimbilio Fiction. He has taught English and writing both in the United States and Thailand. He currently lives in Missouri and co-hosts the podcast Poet in Bangkok.

Interview:

Benjamin Woodard: We’ve known each other for about seven years, first as schoolmates and friends in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and then when we worked together at Atlas and Alice Literary Magazine, but for those who only know you through your essays and stories, could you give us a bit of background on you as a writer?

Donald Quist: Seven years! Amazing. It’s really good to know you, Ben. So, I’ve been piecing together poems, plays, short stories and novels since I was five, but the majority of the work I did before 2007, I fully admit, wasn’t worth sharing. I think after finishing college I became more focused on producing better work, stuff that wasn’t just serving my ego. Part of it was growing out of solipsism. When I made this mental shift, when I adopted the ethos of writing for others, to affect some measure of change, I found my voice and it started connecting with people. It started with one acceptance to a literary journal, then another. I started a blog on Tumblr and folks started following; I crowd-funded a short story collection (Let Me Make You a Sandwich) and all of this led me to grad school, where I met you and a bunch of other people who supported me, who helped me strengthen that voice and shape it into something useful. As a writer, I want to be useful.

You know, this question you’ve asked is kind of tough. It makes me think about ideology as a writer. Maybe, because I also very much identify as an educator, when I’m asked to explain who I am as a writer I immediately want to give something like a teaching philosophy.

Speaking of which, you’re now in a Ph.D. program in Missouri.

Speaking of which, you’re now in a Ph.D. program in Missouri.

Oh yeah, just started.

As a writer who has gone through an undergrad, an MFA, and who is now starting a doctoral program, do you look back on any of your early influences and cringe, or are they still helpful to you?

I was just thinking of this earlier today in a class on pedagogy. I was asked to reflect on my intellectual influences. At first I felt this pressure to scramble for revered names in literature and acclaimed texts on theory and practice. But, ultimately, I’m learning to embrace the stuff that first inspired me, and in many ways continues to cast a bright shadow over my work.

I approach everything I make with a pop-punk sensibility. I do. I must accept that. I can see bands like Yellowcard or Taking Back Sunday in much of my prose: a frenzy punctuated by moments of harmony, alternating between tones, with dramatic shifts and an overarching message that we are equipped with what we need to make a better life for ourselves.

Also, I am always going to list Jerry Springer as an influence. And the compassion I strive for was embodied in his “Final Thoughts” at the end of each episode.

The ethical dilemmas that Peter Parker has faced as Spider-Man correlate to my predilection for exploring nuance, my tendency towards complicated characters who often hurt those around them in an attempt to follow what is believed to be a greater purpose.

Those themes certainly run throughout the collection.

Yes. Thank you, Spider-Man!

You mentioned compassion and trying to help others through your work, and I wonder if you could expand on what you mean by that.

Here’s where I might start getting didactic, but I will preface this by saying I don’t believe any aspect of writing can or should be prescriptive. Okay, Hippocrates is credited with the concept behind “Ars longa, vita brevis”: life is short, art long, opportunity fleeting, experience treacherous, and judgment difficult. That feels true to me. It feels true to me that there cannot only exist one truth, one correct perception of events. If I accept my boy Hippocrates’s assertion, then the work I put out into the world must also follow this belief. If my writing is not serving to help broaden understanding, challenge isolationism and apathy, I’m not using the skills I’ve cultivated effectively.

With my work, I hope to provide anecdotes confirming a bias of openness. I hope to reinforce the idea that the gray between black and white rhetoric is worth inhabiting and to encourage others to examine the boundaries of their perception. Looking past oneself is the basis of compassion. I write about people much different than me because it provides the opportunity to move beyond myself. Ideally, these narratives might provide readers a chance to widen their worldview as well.

With that idea in mind, let’s talk specifically about the new collection. The title, For Other Ghosts, first appears as a part of a line of dialogue in the story “A Selfish Invention,” but I wonder how, to you, it represents the book as a whole.

When I first conceived For Other Ghosts, I created a paragraph-long description: the aboutness of the book. For over five years I wrote and revised with that description in mind. For me, this collection is very much about the effects of globalization on cultural identity, how we choose the stories worth telling, and who has the authority to tell those stories. “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter” is one of my favorite quotes by Achebe. Building upon this notion, I think privilege structures (as Maggie Nelson says), and privilege are in constant flux. I live as a lion and a hunter, as predator and prey; I’ve been the rifle and I have teeth. For Other Ghosts wrestles with this awareness.

The title, like the line it evokes in the book, is a dedication to those that have felt marginalized and made to feel invisible, those hunted systemically. It is a reminder to those who feel othered that they are not alone. It is a promise and a plea to those who read the book: my promise to—my plea for others to—use varying levels of privilege to try to lessen human suffering.

One small moment that happens early in the book’s first story, “They Would Be Waiting,” talks about how we sometimes purposefully misremember those who have died, or decide to change their history, in order to be kind to their memories. This seems to tie into what you’re talking about here.

Absolutely. In that story, the speaker points out the inconsistency of public memory, how events and people can be edited to fit into narratives that are easier to digest. It would be easier if all our heroes were not human.

This is something I feel we’re all guilty of.

I’ve definitely struggled with this. “They Would Be Waiting” explores a common tendency to sanctify our dead. It might be viewed as an act of compassion. But I’d argue that compassion and social obligation often get confused.

Frequently, we don’t seem to know how to navigate the death of a family member, or any huge loss, and that line between compassion and obligation blurs.

Compassion does not mean ignoring all that makes a person problematic. We alter history in what we believe to be an act of love. But to love is to acknowledge history, to examine, to learn, to bring failings to light and then try to do better. So I choose difficult characters. I place them in difficult situations. And I try to see if I can get myself to love them.

Nearly every story in the collection pivots on some sort of major loss or gain, a beginning or ending, so you certainly set characters up for a test of their own humanity. Do you ever put a character in a situation and decide, “This is too much”?

Oh, yeah! In the story “Twin Pilgrims” I worried at one point during the writing process, “Could the circumstances surrounding Geri, the protagonist, get worse or more complicated?” There are layers of loss. But as I progressed, I encountered a moment when I felt empathy for Geri. I remembered all the pain she had inflicted on the supporting characters, and yet I could still feel compassion for her. I felt the piece beginning to succeed.

Geri is a complex person in that story. She does some horrible stuff, but then also says things like, “I walked around town for hours trying to decide if I could ever find what I wanted,” and her longing and confusion suddenly feel relatable.

That story started with a challenging idea: what if, despite the reprehensible things we do, we might all still be deserving of love? I don’t attempt to answer that, but I felt it worth exploring.

You leave that open for the reader to decide, which I admire.

Thanks! Do you find yourself writing about difficult people in your own work?

Yes, at least I think they’re difficult. I’m currently working on a story where the main character is obsessed with correcting a very minor wrong, which ultimately makes him difficult to like. And I have another story floating in submissions that’s narrated by a character that ultimately is the problem he’s trying to solve, but he can’t bring himself to realize it. So I’d define those characters as difficult, even though I kind of love them.

Yes, at least I think they’re difficult. I’m currently working on a story where the main character is obsessed with correcting a very minor wrong, which ultimately makes him difficult to like. And I have another story floating in submissions that’s narrated by a character that ultimately is the problem he’s trying to solve, but he can’t bring himself to realize it. So I’d define those characters as difficult, even though I kind of love them.

I look forward to reading both of them.

Here’s hoping they find homes! So, speaking of reading, I remember workshopping “Testaments” forever ago and was happy to see it in the collection.

Hold on for a moment, when do you know you’re “falling for a character”? When do you know it’s love?

That’s tough to say. Sometimes, I fall for them immediately, because I’ve placed them in a situation that makes me root for them. Other times, they end up saying or thinking something that, when I read the writing back later, hits me in the gut. What about you?

I feel for the mother and daughter characters in “Testaments” for reasons similar to those you just listed. I put them in a situation that made me root for them and each of them began to reflect aspects of my own personality, namely, the conflict I have between my inherent skepticism and my desire for faith.

“Testaments” is one of a couple stories that haven’t been published previously, and it also contains a minor character that shows up in another story. How did including these previously unpublished stories in the collection come about, and what made you decide to introduce character crossover?

I kept returning to “Testaments” after that graduate school workshop. While other pieces from my MFA thesis were abandoned, “Testaments” kept getting reshaped and revised over the years.

I feel like the decision to include this story was instinctual. “Testaments” was a story that couldn’t find the right home at a journal. It’s longer than most places are comfortable with. I still hadn’t totally figured out what I wanted to do with the point of view. The themes tied to the scope of the book and I saw an opportunity to thread it tighter by mentioning one of the characters from “Testaments” in a piece that would be composed later.

Seeing that name pop up in another story was a nice little Easter Egg. If I’m right, there’s one other character that has a similar cameo, yes? (I’m trying to remain vague so as not to ruin the discovery for other readers.)

Yes, thanks! To write For Other Ghosts I used a lot of mind maps, and I realized that the story “#CookieMonster” is where a lot of the threads converge. The story is largely about the role the internet plays in the modern justice system and how it can give online spectators a false sense of familiarity with a particular case. This narrative is constructed in the form of a series of search engine results, and in the comments section below one of these web results I united several characters from throughout the book. I wrote For Other Ghosts with the intention of multiple reads. I like media you can return to and discover new things. So the book is linked conceptual and narratively.

Now I feel like I need to read it all again to see what I missed! Shifting gears a bit, this is your second book with Awst Press. Do you feel you have greater control over your books when working with an independent press?

I love working with Awst. They’re attentive, and the benefit of a small press is having so much input in the making of the book. It becomes very much a collaborative effort. Everything from cover art, to font, to promotion, I get to play an active role in how the manuscript becomes a book that moves out into the world. I don’t want to totally romanticize it. It also means a lot more work and greater expectations on me to be involved with these narratives long after I’ve finished writing them.

And you’ve used the same cover artist for both books.

Maggie Chiang completed the cover illustrations for Harbors and now For Other Ghosts. She worked with art director L.K. James at Awst Press. They’re incredible and I’m super happy they both wanted to work with me again.

I could keep peppering your with questions all day, but I guess we should wrap it out with one last question. For Other Ghosts comes out in October, you’ve just started your Ph.D. program: It’s cruel to ask, but what comes next for your writing?

Not too cruel at all. I’m working on another collection of nonfiction inspired primarily by Pensées by Blaise Pascal and Maude Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks. This book aims to examine the mythology of black male criminality. It’s called To Those Bounded. I’m also working on bringing my narrative podcast, Poet in Bangkok, with Colin Cheney, to a close.

To Those Bounded sounds excellent. I look forward to reading it one day. Thanks for the chat, Donald!

Thank you! This has been so much fun. Thanks for giving me so much of your time today. I appreciate it.