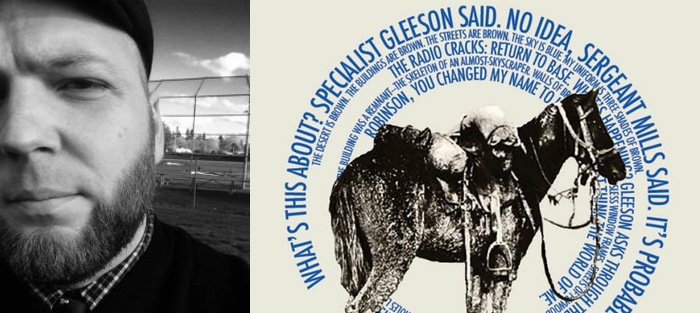

Memorial Day is dedicated to honoring those who have given their lives in the service of the United States Armed Services, the fallen remembered by soldiers, veterans, and civilians alike. Veteran and author Matthew Robinson honors their lives and military experiences in his co-authored collection of homecoming stories, The Jesus He Deserved (Reprobate/Gobq, 2018), as well as in his debut novel-in-stories The Horse Latitudes (Propeller Books, 2016), which follows one Cavalry platoon’s time in Baghdad, Iraq.

The Horse Latitudes, which was a finalist for the 2018 Oregon Book Award, depicts the physical and emotional battles soldiers face when boredom gives way to mortar fire, IEDs exploding, single sniper shots fired, and stabs of homesickness. Through alternating points of view and conflicts both external and internal, they face what it means to fight and die in war, and what it means not to. Described as “bold and radiant and spare” by Leni Zumas (Red Clocks) and “remorseless yet compassionate, bone-dry yet fierce as the desert winds” by Diana Abu-Jaber (Birds of Paradise), Matthew Robinson portrays each soldier’s perspective with a careful emphasis on individual experiences in modern day warfare.

Matthew Robinson is a recipient of a 2016 Oregon Literary Fellowship, and his fiction has appeared in The Road Ahead (Pegasus Books), Grist Magazine, O-Dark-Thirty, Word Riot, Split Lip Magazine, Clackamas Literary Review, and elsewhere. He served six years in the Oregon Army National Guard, deploying to Baghdad, Iraq in 2004, and he currently teaches creative writing at Portland State University, which is where Matt and I met first met.

Interview:

Thea Prieto: I know Memorial Day is a time when you plan two special get togethers, one with your family and one with your army buddies from your 2004 deployment. Would you mind sharing some of your thoughts about Memorial Day and what it means to remember with civilians and with veterans.

Matthew Robinson: In 2005, I returned from deployment and left military service. The fourteen years since have been an ongoing reintegration for myself and the soldiers with whom I served. The U.S. continues to maintain troop presence in Iraq and Afghanistan. Currently, tensions with Iran are escalating. Yet day-to-day civilian life here is fantastically distanced from all of it. More and better books are being published about the current wars. More films are being made. But the disconnect between those who vote and those who serve on their behalf seems unchanged to me. So around this time every year I try to be more vocal about this disconnect with my family and friends. We talk about what responsibilities, if any, citizens have for these wars. What we as a country have paid in lives for them. Because I need for them to think about it—not to have answers (I don’t have any either), but to have the conversation. In all these years, the thing I want most is to have a better conversation.

Of course, this disconnect isn’t just on the civilian side. Veterans I’ve talked with, though similarly frustrated, readily admit their closedness to dialogue. We want to be understood, but we don’t want to, or feel unable to, share our own stories. We hold civilians accountable for the actions of their elected government, but we’re still wrestling with our own service to that government. So every year I meet up with people I’ve served with, and we visit the cemeteries where our dead are buried. We mourn and talk and are quiet and tell old stories and tell new stories and ask questions and cry. And every year I feel better about the people on both sides, and I still want them to somehow get closer together.

I can see how the want for conversation and new and old stories would lead you to writing.

I can see how the want for conversation and new and old stories would lead you to writing.

Exactly. Initially, my writing of The Horse Latitudes was a lot of me trying to unpack my own deployment by exploring a very fictionalized version. But in the four years it took to write, I met with my guys, shared drafts with other writers, met Blue Star Family members at readings and in classes. The stories began to reflect these interactions—a novel with specific constraints about how much civilian life would be allowed on the page became a kind of discussion across the divide. Everything sort of broadened.

For example, within the book there are a series of letters written by the character Stone to me, the author, telling me how displeased he is with my attempt to share ‘our’ stories. The shape of those letters came from a class exercise assigned by Leni Zumas in which we took something in the works and played with its form. The content came from a need to acknowledge that no two people experience the same event identically, and this may contribute to what I sense as apprehension by some vets to share their stories—a fear of having their lived experience contradicted. Finding the second narrative form created a kind of paralleling that made the content possible, in this case as a literal dialogue.

That dialogue between your characters, which widens into a dialogue between your characters and yourself—I think it successfully draws the reader into the conversation, asking them to question their own experience of the warfare they’ve been reading about. And that broadening of the discussion—after you discovered the self-referential letters for your novel, how did the point of view have to adapt to the second narrative form?

From early on in the writing, the POV started moving around naturally as I came to each story with new questions, and the best narrator for attempting answers was different from story to story. And after enough time with these characters, I began to find my own biases. Hicks began to be reliably disappointing and distanced. Sawyer was annoying. Napes tedious. Especially as they appear in Mills’s narrations. I think it’s why Hicks, as Stone, writes the letters. I never got a first-person out of him, so the letters open up a dialogue with him. Sawyer eventually begins to stand his ground in “Bleeder.” Napes speaks in “The Combo.” I didn’t want the entire fictional platoon writing letters to me after the deployment, so they found room for their half of the conversation in their own stories.

I also, though, found limitations to what POV could open up. Top, the company’s first sergeant, never tells a story. Kurtzson doesn’t either, not in first-person. I think this stems from their disinterest in any dialogue. They are both in leadership positions. They think and operate top-down. Neither would care, for example, when Napes and Burnside hold hands, whose thumb flicks the other’s like a selector switch. They would care about the infraction of same-sex hand holding. We are too far apart. This limitation is important. Though every event can be experienced in myriad ways, some perspectives lead to more shaming, isolating, and endangering of soldiers than others, both during their service and after. I negotiated POV among these stories in part so as to de-emphasize these dangerous perspectives for the sake of the dialogues I was and am interested in improving.

To de-emphasize, in your writing, the perspectives that you saw were already, in reality, isolating the experiences of others. You mentioned earlier the isolation or disconnect between veterans and civilians, as well as among veterans, a disconnect where lives are at stake, and you suggested stories about and by individuals as a possible bridge. And we’ve also talked about how these kinds of stories can be better portrayed by storytellers who entertain different points of view and exercise an awareness of perspective. Would you mind sharing how this dismantling of a singular war narrative, or a national war narrative—through shifts in points of view and different narrative forms—was a part of your homecoming as well as your writing?

It was primarily my exposure to so many voices when I began my reintegration. Even before I began writing, men I’d served with would share stories with me about things that had happened on deployment. Obviously, this isn’t unique to military life—all shared experiences have this. Our recollections would often differ. What happened, when and how, to and by whom. What it felt like, what it means. Memory is tricky business. And so these discrepancies became necessary as I began to write these fictional stories about fictional characters—they needed this specific tension built into their bones.

Then, I would workshop them in primarily civilian workshops. A thing would often happen when I visited with vets: the entire civilian population collapsed into the tidy grouping of they—a catch-all for everyone who never had, didn’t now, and never would understand a goddamn thing about it, us, anything. I’ve been guilty of this many times. But in these workshops, these civilians would time and again prove us wrong. They read carefully, asked difficult questions, showed a great deal of heart, and called me on my shit. They, too, had wildly varying perspectives on service and sacrifice and duty, and, contrary to what many vets believe, find value in veteran experiences.

I’m glad they do, and I’m glad to hear there are venues for this kind of conversation. When you mentioned earlier your exposure to many voices during your reintegration, I immediately thought of your story “Hypervigilance” in The Jesus He Deserved. “Hypervigilance” includes, through content and form, different voices, some in dialogue but also some separate and secluded from the others.

That piece in particular is interested in the voices returning veterans encounter post-deployment, so as a single character experiences varying kinds of violence and conflict and support, I resist using exposition to provide context for each encounter. The result is a sort of onslaught of dialogues with no corporeality. He interviews for a job. He debriefs a coworker. He argues with a neighbor, and his wife, and a counselor. But it’s just one after another after another, with no connective tissue. This seems true to my experience of navigating stressful situations after learning that I have a changed, possibly diminished, system of dealing with them—they compile and compound and begin to function as an ever growing mass of conflict. He is interacting with all of these voices, but they become indistinct, part of a single thing—a they. The worst part, for him and for me, is that most of the voices are trying to help. They love him and care about him and are as afraid as he is. The exploration came first, with triggering events leading to increased isolation, and the form followed.

This would have been impossible within The Horse Latitudes. One constraint I’d set for it was that there would be no before or after the war—everything that happens in present action has to occur on deployment. The stories I contributed to The Jesus He Deserved are not deployment stories. They either occur after (like “Hypervigilance,” “Over-Sharing,” and “Tidal”) as various characters reintegrate, or they occur before (like “Sleepover” and “Invisibility”), when their masculinities are first being formed and informed by early events—experiences that eventually contribute to their enlisting in the first place. This is because we all encounter voices that linger, that we stay in conversation with the rest of our lives. They inform future conversations—some more persistently than others. This collection has allowed me to put these voices from before and after next to each other in a way that I couldn’t in Latitudes. And they sit next to stories by Sean Davis and Jacob Meeks, two writing veterans using both fiction and nonfiction in their explorations of these similar themes, so a lot of things are in conversation in this collection.

Interesting, especially your investigations of masculinity, the kind that might lead a person to enlisting and later inform a certain military experience. For example, the last story of The Horse Latitudes is dedicated to the soldiers sharing their grief with each other, and the young narrator in the “Sleepover,” who is face-to-face with grief for the first time in his life, finds himself on the outside of two examples of male grief.

Grief is so often relational. There are the losses that we experience viscerally, that hurt instantly and without any negotiation. Family and close friends. But in the example you mention, “The Rifle,” every man in the platoon is experiencing their grief for a soldier killed in action, and because they all knew him to varying degrees, they are negotiating their mourning individually, based on their understanding of their own relationships with the dead soldier. I find it interesting how each interrogates their treatment of the man, their private thoughts of him, their public behavior toward him. The process sometimes gets surprisingly far from the deceased, becoming more about the mourners grieving their own futures, futures in which they might have been better people, treated that dead kid better than they ever thought to. In this grief, as in the performance of their combat duties, they have to reconcile the performative aspects with the functional efficacies of their masculinities. A grieving body is like a power generator. If that body doesn’t cry or vent or exert physical force, energy builds up. This energy affects perception, patience, access to empathy, higher levels of reasoning, and is carried in the muscles that operate humvees and machine guns. “The Rifle” is about how these men navigate grief energy, constrained by the masculinities they’ve ended up with, in the face of an ongoing deployment.

“Sleepover” is also about relational grief, in this case, because the narrator doesn’t know that the kid he’s staying with recently lost his mother. The narrator, though sad for this kid, feels no grief for the mother. For the first time he considers what a loss like this might mean, and is shown two ways of grieving, which are both examples of related masculinities. Downstairs, the narrator sees his host’s father hiding away in his den, crying, isolating while his son is upstairs. The son is exercising his energy with gore-porn horror movies and intense fight training. Grief looks like whatever grief looks like—the story doesn’t take a position regarding this family’s fallout. Rather, it is concerned with what this narrator might take from this sleepover, his first brush with grief. If he feels shame at seeing the father’s hidden sobs, if the violence of his host’s horror film forever tinges what trying to look hard might mean, he could end up like Mills after he enlists, crying somewhat easily and openly, and having a greater resistance to casual violence than others. If he sees something of value in their isolation, if he sees strength in his host’s ability to perform as tough in the face of great loss, he may become Sawyer, paying kids to fight because it’s a familiar-feeling distraction, or Napes, isolated on the inside and highly performative in his masculinity (fatally so) around his comrades. For both narrators, grief is the catalyst for either constructing and confronting their masculinities.

I appreciate all these thoughts, about the way people grieve in relationship to themselves and their communities, and how grief speaks to identity. It reminds me that grief, especially for the people closest to fallen soldiers, is an important part of Memorial Day. Are there any books or resources you’d recommend to soldiers, veterans, and civilians when they’re remembering this Memorial Day?

Memorial Day can be an opportunity to cross divides as we conduct our rituals and remembrances.

Soldiers and vets, don’t be so stingy with your stories—the families and friends of the fallen will find value in hearing them. Not the epics, and not the worst of it. Share the mundane, the funny, the quiet. David just wouldn’t call me Matty—had to say Sergeant Robinson. Justin loaned me Fight Club before he died. I still can’t read more than a page or two. Other Justin, man you should have seen his impression of . . . . And Erik, well, you know. And for this, they will tell you their stories. Go slow. Nothing has to happen in them—this isn’t entertainment.

Civilians, talk with vets without expecting too much—most of us are new to this, and it’s scary. Be wary of vets who seem to have it all figured out, but still, listen. And ask questions and disagree freely, and we all should acknowledge the righteous hindsight we all have now but so few of us had in 2003.

Books that are helpful to anyone interested in a better veteran and civilian conversation: Home of the Brave by Donna Bryson tells the true story of an entire town coming together to serve their returned veterans; in his memoir, Eat the Apple, Matt Young confronts every inch of his masculinity by interrogating his service as a Marine, its precursors and aftermath; and my two favorite novels about coming home are Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann and Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko—two very different stories, following Vietnam and World War II respectively, of the lone survivor of a battle that ended his entire unit and a group of Native American veterans as they return to the reservation after serving in the Pacific. All of these have helped me better understand my own service and value the sacrifices so many have and continue to make.