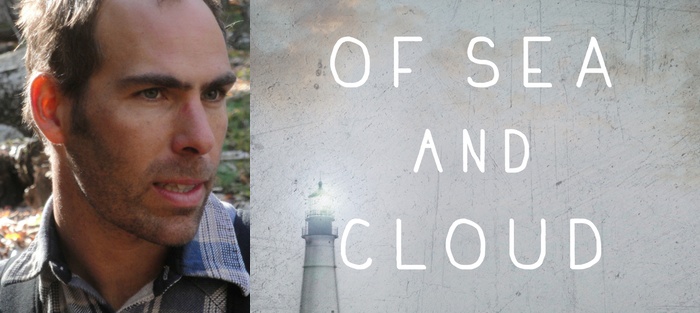

Jon Keller’s debut novel, Of Sea and Cloud, released this summer by Tyrus Books, is the story of Bill and Jonah Graves, two brothers and born lobstermen. They grew up learning the trade from their father, Nicholas, in the severe and beautiful waters off the coast of Maine.

But their humble living is threatened when Nicholas Graves is mysteriously lost at sea. Osmond Randolf—the father’s former business partner and town minister—seems to know more than he’s letting on. The market price of lobster drops precipitously, and the Graves brothers are barely able to make ends meet. Randolf courts large international conglomerates and further threatens the legacy fisherman. Bill and Jonah know that they must take a stand, but they can’t agree on how much they’re willing to risk.

Of Sea and Cloud mixes elements of murder mystery with a Hamlet-esque meditation on revenge and its consequences. Partly an homage to the great seafaring novels of the canon, at its core it is an elegy for a dying way of life. Even as he subjects them to insurmountable economic and environmental forces, Keller manages to treat the Graves Brothers with a wealth of compassion.

Anthony Doerr, author of All the Light that We Cannot See, has called the book “a gorgeously written exploration of faith and loyalty, love and dishonesty.” He goes on to say, “I will never forget these characters, these waters, or the harrowing dramas unfolded upon and beneath them.”

Interview:

Tyler McMahon: Could you talk a little about the origins of this novel? How did Of Sea and Cloud get started?

Jon Keller: After graduate school, I moved to a remote part of the Maine coast to work on a lobster boat. I’d been in Montana and Idaho for twelve years. The seascape amazed me; not just the beauty, but the starkness of it all, so absolute and consuming. For weeks on end, the world could go cold and gray in a way I’d not witnessed—so many subtle and varying degrees that were both harsh and beautiful. I was working on a lobster boat, so I spent huge amounts of time watching the water and the sky because there was nothing else to look at but lobster bait, which is just dead fish.

In the winters, I worked at a lobster pound—not a restaurant or market, but a real outdoor lobster storage facility. Basically, a fenced off cove that fishermen store tens of thousands of pounds of live lobsters in until the market improves. I worked alongside a crew of local guys, and each day I went home and wrote down everything I could remember from the day’s work—things they’d said, things that happened, ideas that popped into my head. Gradually, I came to understand that a book would evolve out of those notes.

Even so, I felt guilty for wanting to write about the lobster fishing world because it was such an old and insular place, and I was so new to it. It took me two years of working on the boat, and at the pound, before I began to write. In addition to my notes, I’d written a bunch of research-based articles concerning the economics and politics of commercial fisheries for a monthly paper, but when it came to the culture, I felt that I was touching on something nearing the sacred, and to write about the locals would be a form of trespass. Fiction writers have a serious responsibility, especially when writing about something that others view as sacred—and on the downeast coast of Maine, the entire culture is wrapped around the lobster industry.

Then one day, while working on the boat, it dawned on me that I could spend a lifetime on the stern of a boat. By then, I felt like I’d put in enough time to not be a total interloper.

At the same time, I’ve lived enough places, and in enough small towns, to be aware of when a place is undergoing a serious shift. It’s a cultural unraveling, and it results in loneliness and desperation that I hoped to capture in the book. There’s the confusion that comes about when a sub-culture doesn’t evolve as quickly as the culture that surrounds it. The technology has changed, the standards of living have changed, the world has changed… yet the way of life has not, and the result is a cultural tailspin, a potential breakdown.

Isolation, I think, works backwards in this case; instead of safeguarding a place from the onslaught of a global economy, the isolation exposes it. Many young fishermen are no longer learning to care for the industry the way their fathers and grandfathers had; instead, they take out huge loans and buy huge boats and catch unprecedented numbers of lobsters. The captain I worked for was of the older generation, and he talked often about the changes he was seeing—the younger generation’s apathy, the infringement of big business, the loss of waterfront access. It was all happening at once, and I tried to capture that whirlwind in the novel.

Were you thinking about any other texts? In particular, were you inspired by any of the canonical stories of nature, fisherman, or the sea?

When I’m writing, I look at the books that I read as ingredients, kind of like sautéing in your head. I’d had trouble with plot in the past, and so I looked to some plot masters who are largely ignored by academia—I read a bunch of Dumas, Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, John D. MacDonald, even some James Lee Burke. While reading the books, I’d map their plot lines on big pieces of paper, then write myself reading responses as if I were in a class. I wanted to see how they did what they did, because it seems that so many literary novels these days just flat lack a good old-fashioned story. And isn’t that the point?

When I’m writing, I look at the books that I read as ingredients, kind of like sautéing in your head. I’d had trouble with plot in the past, and so I looked to some plot masters who are largely ignored by academia—I read a bunch of Dumas, Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, John D. MacDonald, even some James Lee Burke. While reading the books, I’d map their plot lines on big pieces of paper, then write myself reading responses as if I were in a class. I wanted to see how they did what they did, because it seems that so many literary novels these days just flat lack a good old-fashioned story. And isn’t that the point?

At the same time, I was reading Robert Alter’s translation of Genesis, and the Robert Fagles translations of Homer, and flipping through Milton again, so all of that stuff was pounding around in my head while I was standing on the lobster boat looking at the sea and sky and coastline. I soon began to see within the land and people something nearing the epic.

I worked—bizarrely enough—for a captain who’d gone to Wesleyan, and he quizzed me nearly daily on the classics—the Greeks, Shakespeare, the Russians… I’d ask him how many traps we had left to haul that day, and he’d ask how many sonnets Shakespeare wrote. If I answered incorrectly, he wouldn’t answer my questions.

That’s fascinating. What did you learn from those self-taught lessons on plotting? How did those plot-line maps manifest themselves in the story of the Graves brothers?

I re-realized the value of stories. Somehow, I’d lost that during school. I wanted to write a story that moved quickly and had a lot happening on every level I could fathom; character and setting have always come rather intuitively for me, so I didn’t worry about those aspects—I just wanted the book to have a story beyond a bunch of people walking around being ironic and/or introspective.

I also learned the importance of coincidence in fiction. The use of coincidence in plot lines goes a long way in separating a well-crafted plot from a poorly crafted one; the poorly done book might still captivate the reader’s attention, but it won’t stand up to very much scrutiny, while the opposite is true for a well-plotted novel. That’s a reason why genre-talk can be so tiresome and irrelevant—Raymond Chandler novels are fantastic when looked at through any lens, whereas there’s some pretty weak “literary” fiction floating around these days.

When I started Of Sea and Cloud, all I had in my head was the image of the two brothers standing on the wharf in the rain. There was the old bait house and the gulls and the stream of fish blood that I stepped over every day on my way to and from the lobster boat. The Graves brothers came from that image. Shortly afterward, while working at the lobster pound, the guys I worked with got talking about how long it would take for a body to disappear if it ended up in a lobster pound (i.e., how long would it take for the corpse to be eaten by lobsters), and I knew that somehow I needed to get the body into the pound… but I can’t plan a scene and then write it; that never works for me.

Drawing the maps helped get my mind working with plot lines; plot slowly became more sub-conscious. I’d write a hundred pages or so, and literally draw out where the novel had been and where I suspected it was going, then I’d go back to the drawing board. Usually, I’d end up deleting a huge amount of what I’d written, and then I’d veer the story in a different direction; most of the “veering” was done once I had the text written—tons of small changes adding up to large changes. But that’s how I work. I write fast, delete tons, and edit forever.

Your sister is also a novelist, correct? What’s it like having two fiction writers in the same family? Do you two talk about the craft?

My sister is Abi Maxwell. She wrote the novel Lake People.

We’re pretty close. It’s great having two writers in the family. People tend to assume there’s some degree of competitiveness, but there isn’t. Her book was published a full year or more before mine, and that moment sticks in my mind. I got her phone message on a cold, wet day. I’d hiked a couple miles across an island to dig clams in a remote spot where I thought I could do well, earn some money. The wind was howling and the rain and sleet were blowing sideways, so I had my hood cinched tight and my waistline cinched tight and my head down. I had to make two trips across the mudflats and across the island to get my clams back to my truck, carrying them in a pack basket on my back, cold muddy salt water dripping down my pants. When I finally got in the truck, and warmed up some, I got the message that Knopf had bought her book.

It was awesome! It didn’t seem quite real to me, that finally one of us had a book heading out into the world… I just sat there, listening to the rain on my truck. Perhaps it was the cold, but once the idea of her publishing sunk in, I had a moment of seeing myself from the outside—there I was, covered in mud, soaked, exhausted, in pain, alone out in the middle of nowhere, digging clams for 80 cents a pound while she was signing papers with Knopf. What the hell was I doing?

It was awesome! It didn’t seem quite real to me, that finally one of us had a book heading out into the world… I just sat there, listening to the rain on my truck. Perhaps it was the cold, but once the idea of her publishing sunk in, I had a moment of seeing myself from the outside—there I was, covered in mud, soaked, exhausted, in pain, alone out in the middle of nowhere, digging clams for 80 cents a pound while she was signing papers with Knopf. What the hell was I doing?

Soon I got a few phone calls from friends and family who thought I’d need to be consoled, and all of that forced me to reevaluate some things in my life, and one of the realizations that I came to was how important my non-writing work has been to me—I was proud of my sister, and equally proud of the fact that I was earning a living out there on the mudflats, or on the stern of a boat. The jobs I’ve had have sculpted my writing, and taught me things that no amount of research could ever teach me.

Abi and I talk about writing a fair amount, though I’m not much of a craft-talker. I’d rather talk about clams or lobsters, horses or mules. Writing to me is personal, and it takes a bottle of wine or two to open me up. But my sister has been a valuable editor for me. I don’t read her stuff, in part because I’m not a good editor, and in part because she’s careful to not let my big brother influence take over her writing, as it had when we were younger.

I’d like to hear more about writing while holding an unrelated job. In graduate school and whatnot, I assume you wrote in a more academic setting, surrounded by other writers, attending workshops and literature classes. How would you compare that experience to writing novels while making a living with lobsters and clams? I don’t just mean the mindset, but also the process. Is it easier or harder to find the time and energy to work at fiction, when your livelihood is completely separated?

That’s a great question because this has been a central struggle for me as I writer. When I first started on the lobster boat, it was a relief. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I was trying to get as far from academia as I could, and I think—short of moving to the tundra—I succeeded.

But of course the writer in me slowly came out, and I began writing on bad weather days and through my time off during the winters. The boat and the culture and the geography had given me a huge burst of energy, and I wrote the first draft of the novel pretty fast, knowing the entire time that I’d have a ton of editing to do. It didn’t take long to realize that I’d never finish the editing if I was going to keep lobster fishing full time, so I turned to digging clams because the days are short and I wouldn’t have to answer to anyone—if I wanted to skip work in order to write for a week, that was up to me.

Ideally, writing and clamming fit together perfectly—clamming is physical and super intense, a bit akin to hard running—but I often found myself stuck between the two because they require such different mindsets, both of which are exhausting. In truth, they do feed each other in a productive way, but I couldn’t do both in a day, and at times it was hard, both financially and culturally, to justify skipping work in order to write.

What it comes down to, though, is that the work I’ve done and the people I work with have kept my head in a place where I need it to be. By that I mean that as a writer, I spend a huge amount of time in my own head, thinking about story and plot and metaphor, motivation and reaction and all of that crap that will eventually drive me crazy if I don’t find a way to mediate it. Some writers drink, some meditate, some exercise, some go crazy. I turn to physical labor. In graduate school, I had a hard time staying balanced, and my writing really suffered because of it.

What it comes down to, though, is that the work I’ve done and the people I work with have kept my head in a place where I need it to be. By that I mean that as a writer, I spend a huge amount of time in my own head, thinking about story and plot and metaphor, motivation and reaction and all of that crap that will eventually drive me crazy if I don’t find a way to mediate it. Some writers drink, some meditate, some exercise, some go crazy. I turn to physical labor. In graduate school, I had a hard time staying balanced, and my writing really suffered because of it.

Clamming and lobstering keep me grounded, and so too does spending time with people who don’t give a shit about books and writing. As the lobsterman I used to work for once said to me, “Not everyone views life as metaphor.”

Even so, there are plenty of times when I’d give anything to have a few friends around who value books and writing the way I do, and who understand a bit of where that side of me comes from. Sometimes, it’s a struggle for me to continue to write while surrounded so completely by a culture built around hard work. Case in point: as I write this, it’s 6:00 on a Monday morning. I live on a sailboat in a harbor filled almost entirely with lobster boats. It’s just getting daylight, and the boats are going by on both sides of me, heading off to haul traps. As the guys go by, I get quite a few: “Get the fuck up, Jon! Time to go to work! Tide’s going! Why ain’t you clamming?”

But I’d take that over a harbor full of guys on laptops any day.