Most everyone has had the experience of listening to a particular song just once, falling in love with it, and then wanting right afterward to buy the band’s album outright. Depending on the song, some of us even pledge to listen to a band’s entire discography after hearing just one of their works, and we’re rarely disappointed by what we come across in our hunt for beautiful art. And for readers, sometimes that same experience can happen after poring through a single short story by an author.

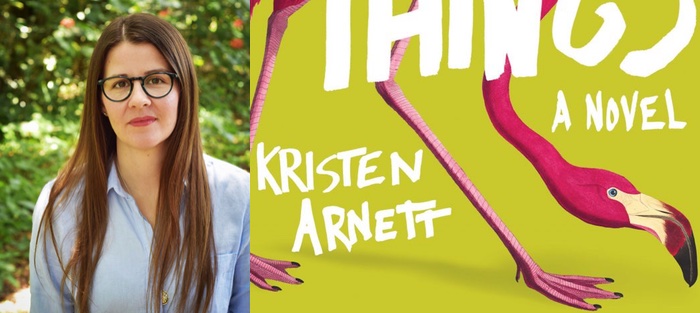

Kristen Arnett‘s “The Graveyard Game,” originally featured in Guernica, is one of those stories. Set in Florida—one of the most prominent settings in Arnett’s body of work—the story is as lush and as dangerous as its backdrop, and it makes you want to read everything else she’s ever penned. Arnett, a queer fiction and essay writer, published her first short story collection, Felt in the Jaw, with Split Lip Press in 2017. She’s been a regular contributor to Ploughshares, and she’s a featured columnist at Literary Hub, where she writes about her (mis)adventures as a librarian. This June, as well, she’s releasing her debut novel, Mostly Dead Things, through Tin House books.

Like much of her short fiction, Arnett’s Mostly Dead Things centers on memory and the carved-out spaces our loved ones occupy. For Jessa-Lynn, the novel’s protagonist, this means wrestling with the memory of her taxidermist father, who killed himself in his own workshop and left his only suicide note addressed to his daughter. Not his wife, Libby, or his son, Milo, but Jessa, his protégé. And then there’s the absence of Brynn, Jessa and Milo’s childhood friend who grew up to steal both of their hearts, and who’s left them wrecked and fending now for themselves.

Arnett and I talked on the phone recently after The New York Times featured her novel as one of the most anticipated summer reads.

Interview:

Barrett Bowlin: Speaking of last week’s New York Times piece, you mentioned that your interest in taxidermy started off with research you were doing for a short story. When did you figure out that this was going to have to turn into a larger, much more involved project?

Kristen Arnett: Before this book, I mostly considered myself to be a short fiction and essay writer. I didn’t think about myself as a novel-length writer at all. But I was at the Kenyon Review‘s writer workshop, which is generative, and I happened to be working on a story about a brother and a sister who taxidermy a goat for a neighbor, and they fuck it up really badly. I was in the middle of looking at a whole bunch of taxidermy videos online, and they were cracking me up, and so I wrote this short story.

So while I was there and working on the story, I was just obsessed with it. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. And when I was done writing it, I was still thinking about it, but mostly about the people and the place I was writing about. And I was thinking about what they were doing and who their family was. That had never happened to me before while writing a short story. Usually, when I’m done, that arc is complete and I’m done with the characters, I’m done with the place. But this was the first time that I thought I was done with something but I knew I wasn’t. I wasn’t done with the people. I was still so interested in them and wanted to know more about them. So it started to sound like a bigger project to me, and having never written anything that long before, I thought, well, this would be a complete trial and error project. Let’s see if I can do this.

So while I was there and working on the story, I was just obsessed with it. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. And when I was done writing it, I was still thinking about it, but mostly about the people and the place I was writing about. And I was thinking about what they were doing and who their family was. That had never happened to me before while writing a short story. Usually, when I’m done, that arc is complete and I’m done with the characters, I’m done with the place. But this was the first time that I thought I was done with something but I knew I wasn’t. I wasn’t done with the people. I was still so interested in them and wanted to know more about them. So it started to sound like a bigger project to me, and having never written anything that long before, I thought, well, this would be a complete trial and error project. Let’s see if I can do this.

I didn’t toss out the story itself, but I did set it aside. I knew I couldn’t just expand the short story into a novel, so I was determined to just think about these people I’d written. I had to give myself a lot of rules and parameters because I’d never written anything that lengthy before. I was worried that if I didn’t follow some guidelines for myself that I wouldn’t finish it. I forced myself to write a thousand words a day, Monday through Friday, and while I could definitely write more than that, I couldn’t write less. If I wanted to write on the weekends, cool, but I didn’t have to. Every week I’d have at least 5,000 words, and every month I’d have at least 20,000, and then, after several months, I thought I’d at least have something book-length-ish. I had no idea if it was going to be anything usable, but I’d at least have the content.

And the second rule I gave myself was that I wouldn’t edit as I went along. I knew that if I tried to touch it, I would stop. So I would only allow myself to read the last paragraph I wrote from the time before, just to see where I was. I wouldn’t go back any farther than that. I think I wrote the guts of the novel from about June 2015 to mid-November. I remember I had well over 100,000 words in a Word document, and then I had to close it up and promise myself I wouldn’t look at it until well into the new year.

It was a mess when I went back to look at it, but I don’t think I would have been able to produce it if I hadn’t given myself those rules in the first place. I knew that if I went back and started nitpicking at the sentence level that I’d get trapped, and I wouldn’t have been able to get the guts of it out, which was really important to me. It was a brand new process for me, and while it was very satisfying, I know that, before the book, I’d never written that way before.

Kind of along those lines, I’ve heard from the author James Charlesworth that writers fall into either the plotters camp (the outliners, the planners) or the “pants” camp, i.e., writing by the seat of their pants and seeing where it takes them. In writing Mostly Dead Things, which camp did you fall into, and is this your normal station for writing?

I’m not an outliner for any project ever. I had a couple of ideas that I knew I wanted to do going into the book, though: I knew I wanted the chapters to alternate, where the present would go linearly, and the alternating chapters in the past would go all over the place. I also knew that I was going to have Jessa’s father die right away and that it would be the kickstarter, but aside from knowing that this was going to be set in Florida and that it was going to be about taxidermy, I had no idea about what these people were going to do. I put together a Word document that had people’s names in it and what I called certain places and locations, but that was it. So I guess I fall into the seat-of-the-pants crowd.

I know I want to be surprised, too, when I’m working. I don’t want to know what’s going to happen because if I do know what’s going to happen, then I’m bored. And if I’m bored, I worry that the reader is going to get bored, too. So when I’m working and writing, I want my characters to show me what they’re going to do throughout the book, and that’s definitely what I did here.

What’s your preferred beer when you’re writing?

I drink a fuck-ton of Steel Reserve, which I know is technically malt liquor, and I buy a lot of it at the 7-11 that’s by my house. They come in these four-packs of tallboys, and if you buy two of them, they cost $7.50, which is less than a dollar a beer. And that’s, like, almost a 9% beer!

And in regards to several mentions of it on Twitter, what’s your preferred purse beer?

Oh, purse beer! I like Jai Alai. It’s a very Florida beer, and I think they’re based somewhere around Tampa. And it’s everywhere down here: you can get it at 7-11, you can get it at Publix. But, yeah, Jai Alai makes for a good purse beer.

That way, you can take a little taste of home with you when you’re on the road.

I can! It’s great.

Thinking about your first short story collection, Felt in the Jaw, I like it that you focused so much on the body, on siblings and twins, on sharing and mirroring. Can you talk a bit about the decision to have Jessa and Milo essentially sharing Brynn as an object for love and obsession?

I was interested in seeing the different forms that intimacy and romance can take, and how messy that can get. For me, I was looking not only at how Jessa loves and tries (or tries not) to understand her feelings for the romantic partners in her life, but also how she experiences intimacy toward her brother or her parents. Or how Milo feels intimacy for people, or how her parents show intimacy for each other. I wanted to look at the different strands and the messy ways that people can love. And I think that because we don’t get to choose how we love people—because your heart just does whatever it wants to—we don’t get to have a chokehold on intimacy. We can try, of course, but I kept thinking about what it would be like to try and love someone that another person you care for deeply also loves. I wanted to see the different shades of how that works.

I also think that different people love in different ways. So, yeah, it felt messy, but it felt like the right kind of messy to see the two of them be in love with this one person, especially because they had all grown up together. And I think that that situation is a natural breeding ground for first loves and the romantic, teenage love that can evolve into something bigger. So the messiness felt natural to me.

I don’t want to call their relationship a “love triangle,” even though that might be the phrase we’d use for it because that’s not quite the shape of what they had. I think that love is just so often messy, and we might happen to love the same people, and it’s different and weird, and that’s okay.

Speaking of love and obsession, you write some amazing sex scenes for Jessa in the book!

Oh, thank you!

With Brynn, for example, they’re secretive and filled with longing, and with Lucinda [Jessa’s current romantic partner], they’re wonderfully out in the open. Here’s the question, then: do you have any favorite books or authors who helped you figure out how to write sex scenes?

Well, I love how Dorothy Allison writes about sex. When I was writing this book, I was thinking about how I wanted to write queerness. And I wanted that queerness to be embedded. I didn’t want a coming-out story; I wasn’t interested in doing that for these characters. But embedding the queerness into the book meant including queer sex in it. I didn’t necessarily need to see tenderness between them, either. Sometimes people just want to fuck.

I feel like we get to see that feeling a lot of the time in stories where there’s a male protagonist, where the fucking can just happen. I don’t think we get that a lot with female protagonists, but I love how Dorothy writes about sex and about how queer women experience sex in all these different kinds of ways. It’s very much true to life, and how she writes is very much accurate in how bodies experience wanting and longing in different kinds of ways. So I wanted there to be a lot of that in the book. That was important to me, not only in just how queer women move day-to-day throughout the world but also how sex functions.

Did you ever get to see Dorothy Allison read at AWP?

I didn’t because I think she was there the year before I started going to AWP. But she is such a bombastic, performative reader. When you hear her read something, everyone in the audience is just spellbound. She’s incredible. I mean, her work is so good on its own, but she is such a performer when she’s reading from it. I love her so much.

Speaking of southern authors, one of the book’s epigraphs comes from Thomas Harris, a fellow Florida writer best known for his Hannibal Lecter novels. I know you’ve mentioned some before, but who else would you add to your pantheon of Florida writers and why?

Obviously, I love Karen Russell. She writes Florida in this way that’s just deeply weird and funny and also tender.

I love Lauren Groff and Lauren van den Berg, too. Oh, and Jaquira Díaz has this great essay collection coming out at the end of this year. She writes about Miami, and those essays are so wonderful that they’re going to murder just everyone. I love how she writes about Florida. And T. Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls is also deeply Florida and is such amazing writing. She writes about Boca Raton, which is a very different kind of Florida.

I love the fact that there are so many female Florida writers who are around and who we’re lucky enough to read. And I like it how so much of that writing is gloriously queer.

Getting into some of the specifics in the book, I like it how Jessa is careful to be honest and direct with Lolee in their conversations. She’s honest and direct and tender with her niece in these conversations, but she doesn’t pull punches. What were the conversations like in your family when you were growing up?

They were not like that. And that’s probably a reason I included conversations like that in the book. My family’s very religious, very Southern Baptist and evangelical, so conversations about sex and sexuality were not very frank. They were instead couched in the question of what God wanted us to do with our bodies, and I found out that these were questions that were mostly just for me. My brother, for example, didn’t get these kinds of questions from my family. He wasn’t told that his body wasn’t his or that it belonged to God, or that he needed to be careful with his body since it was God’s property.

So when I was writing these conversations between Jessa and Lolee, I knew that Jessa didn’t have her own kids, but that she might consider that, if she had a daughter like Lolee, this would be how she would treat her own child. I wondered, then, what those conversations would look like between you and someone you loved but who was still growing up. What would those open and frank conversations about sex look like and about how weird bodies can be. Because those are important conversations to have. And when you don’t have those conversations, you still learn that information, but you learn about it ways that are incorrect. And you sometimes get information that’s plain wrong about sex and bodies, or you’re not getting what you need. You’re just in a dark room all the time.

But I never had any of those conversations with my family growing up, and I wish that I had had them.

There’s a brilliant, excruciatingly enviable line you have toward the end of the book: “It’s a good thing when you can’t stop thinking about a piece. That’s when you know it’s done the work. When you can’t get it out of your head afterward.” I know Libby says it, but is that similar to how you view your own writing, or how when you know something is done?

Would that I could ever think that my work was finished and done and ready! I think that sometimes I just have to peel my fingers away from it. For me, if a work is opening up more questions or creating a type of interrogation, then I feel like the work is doing something. What it’s doing precisely, I don’t know, but I just want it to be doing something. So if I feel like the writing is causing me to think more deeply, or for me to branch out into further thought or into further conversations about the thing, then I think that the work is doing what I want it to do. I just don’t want to sit and allow it to become stagnant. I think that if a piece is just opening up with one thing and is resting on it, and if it’s not opening up other things, then it’s not doing what I want it to do. I guess that’s a way for me to say that I don’t ever really think a work is done, but that I’m excited when a work is doing something, anything further. I want it to feel like it’s constantly moving toward other things, or possibly allowing other people to have further questions and conversations in their own work.

I love the idea of that: of someone possibly reading my work, which might allow them to push into something broader in their own personal experiences while attached to mine. If that can happen, fantastic. I love that.

You’ve written and published extensively, you’ve blogged for both Ploughshares and Lit Hub, you’ve put out both a short story collection and now a novel, in addition to so much else. Looking back, what advice would you give to writers who are just starting to feel their way into the literary community?

For me, the part that was most helpful was just having conversations within that community. None of us know what we’re doing; we’re just kind of feeling our way along. Sometimes you make a decision and it’s a good one, and then sometimes you make a decision that doesn’t work out. That’s just part of learning it since there’s no real process to any of it. I got so much from the community just from meeting people within it—through Twitter, of course, but through conferences and through just talking with people about their work. Seeing how many different ways people write and how we all process things differently was extremely helpful.

I write every day, but I know that not everyone does this. I miss doing that right now since I’m so busy with things, but I really like to write every day. Starting out, I wrote every day and I submitted to a lot of different places. I got rejections constantly, and that was fine with me. Rejections never felt bad because I knew that they were part of this life, and that they were part of what this is. Sure, I got some publications, but when you look at how many rejections I have in my folder, there are just thousands of them in there. But the horrible pleasure and pain of writing is why I sit and do it. And if you’re not doing that, you probably shouldn’t be in it. Because that’s what you’re going to be doing most of the time as a writer: you’re going to be sitting by yourself and trying to work.

But if you find yourself a community of people whose work you enjoy reading and who will read your work, it’s amazing. I feel so lucky just to be able to sit and read so much good work all the time. It’s incredible how much I love it.

So what was the best advice you received as a writer?

I feel like I’ve gotten such good advice and that there are a couple of different things that I would say. For example, I was listening to Dorothy Allison do a nonfiction reading, and she was asked how we would know what would be okay to write about in our lives. And she said that you need to be writing in a way where it’s not only okay for you to be writing about this situation, but also where you can stand not having a relationship with that person in question again. We have to look at these people and ourselves very interrogatively, especially if you’re going to write about another person.

And then there was Mat Johnson’s advice on writing dialogue. He was talking at the Tin House workshop on writing his first novel and how he thought he needed it to be very serious. He said he realized that your work doesn’t necessarily need to be serious; it can also be funny and still be taken seriously. That was so helpful to me because, at the time, I was trying to write so seriously. And I wanted to be funny, but I thought that people wouldn’t take me seriously if I was writing queer things. So hearing someone say that you can be funny while also being taken seriously was incredibly helpful.

Also, it was important for me to hear that writing is 99% being alone, by yourself, in a room and just doing the work of writing, writing, writing. Because if that’s not what you want to do, maybe you’re not ready for writing. It has to be the thing you want to do because so much of it is being trapped with your own brain.

And, gosh, it’s nice to be on the internet. (I can’t believe I just said that!) Sorry, maybe it’s not nice to be on the internet, but it’s nice to have all these wonderful and fantastic writers around, and to be able to pick their brains and see what they have to say about work and how they process it. This is important because I think everyone just works so differently that it’s lovely to see all the wild, wild varieties of ways in which we all work and read and process, and how we enjoy things. I love that it’s just so myriad, it’s so great.

In the research you did in preparation for the book (on taxidermy or otherwise), what was the strangest or most interesting research piece you encountered?

I saw a video from an annual taxidermy conference—I think this one was in Vegas?—and there was a guy skinning a gator, and he was giving all this very detailed information about how difficult it is to skin an alligator. I mean, I’m in Florida and there’s a ton of gators here, but this was coming from a huge, craggy, grizzled dude with a hat on, and he was holding this gator, and he was talking about doing the work of taxidermy in loving detail. He was so intent on describing how they could best leave the animal in its most intact form, but watching him do all these careful cuts with such tenderness and care made for such a weird dichotomy. There was the imagery of watching someone slaughter and cut up this animal, but there was so much tenderness and respect coming from this huge, grizzled man. There was so much love in the act, and I thought, shit, this is how I want to write.

That was one of the most significant things that I watched because it was so unexpected. To this person, this was their art and they loved it, and you could see that through the tenderness he showed. It was wild. I loved it. I couldn’t stop thinking about that video for months afterward.

I know we talked a bit about Florida writers earlier, but who were the authors who helped you figure out how to write this specific novel overall? If you were a video game character, whose work did you have to read in order to “level up”?

This is a weird answer—and hearing my work compared to this person’s book was very delightful to me—but Alison Bechdel‘s Fun Home was something that I thought a lot about. It’s a graphic novel, and it does so much with death and queerness, and family mysteries, and love. But, yeah, reading that made me want to explore family dynamics in my own work, and I knew that I wanted to think about queerness in this way. Also, when I think about taxidermy, I think about it so visually, so Fun Home was perfect for exploring the depths of image. It spoke to me a lot.

I was reading a lot of poetry, too. When I feel like working in fiction, I read a lot of poetry because it’s so heavily image-based within the lines, and even looking at the shapes of the poems themselves helps me. There’s this book by S. Whitney Holmes called Room Where I Get What I Want, and I read the shit out of that book while I was working. It’s such a beautiful book.

And there’s Morgan Parker‘s There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, and then Tommy Pico‘s work. They’re so beautiful, but they’re also pop culture-y and punchy, and there are times when you get to a line and it just smacks you in the face. So, yeah, I sat alone a lot in poetry and thought about the images and how they worked like that, and how I wanted the images to work in my own fiction. But I definitely read a lot of poetry for this.

Last but not least, is there a writing project you have on your plate or in your future that you’re intimidated by?

Oh, god, all of them.

All of them?

I think that if I’m not feeling like that, then maybe I’m not doing the work I need to be doing. Because if I’m working on a project and I don’t feel like that, then maybe that’s not the project I need to be working on. I don’t think I’m invested enough in it, you know? But that’s just how I feel for me.

Right now, I have a draft of the next novel.

Oh, nice!

And I also have a short fiction collection that I’m piecing together, and then I’m working on an essay collection. I wish I had the time to just sit and work on stuff, but I know I have to sit and be patient and wait until my brain has time to do it again. I know I’m very impatient when it comes to wanting to work on my own stuff, but there’s stuff on the horizon, and I’m right now very stressed about all of it, but in a good way.