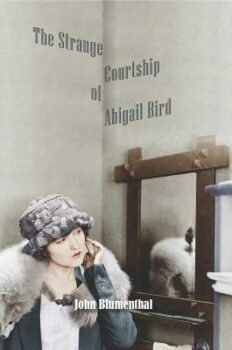

John Blumenthal’s most recent comic novel, The Strange Courtship of Abigail Bird (Regal House Publishing), plays with classic themes of love by way of a courtship that harkens back to the propriety of the nineteenth century. Also seemingly from another era is the novel’s narrator, Ishmael Archer, who speaks like a character from one of the period novels he devoured as a child, having been introduced to great literature by his parents, both English teachers.

The book is a quirky love story centered on Ishmael and his love interest, Abigail, who in the midst of their awkward courtship falls into a coma and loses her memory. So she has not only forgotten her own identity, but that of Ishmael, her paramour. How, then, will our protagonist reconnect with the woman with whom he has fallen so deeply in love? This is the question that animates the dramatic and comedic elements of the novel, but it also allows the book to probe its more human concerns; in particular, memory, identity, and love. What are dreams? What are memories? And how can literature function as a means of discovering unknown truths about ourselves and the world we live in?

It’s been said that a book can transport a person to another world, and I found myself fully immersed in this novel as I followed the courtship of Abigail Bird through the fictional landscape of Highland Falls. If you are looking for a brief escape into a new world—one that can make you laugh and bring you to tears—this is the book to pick up and read.

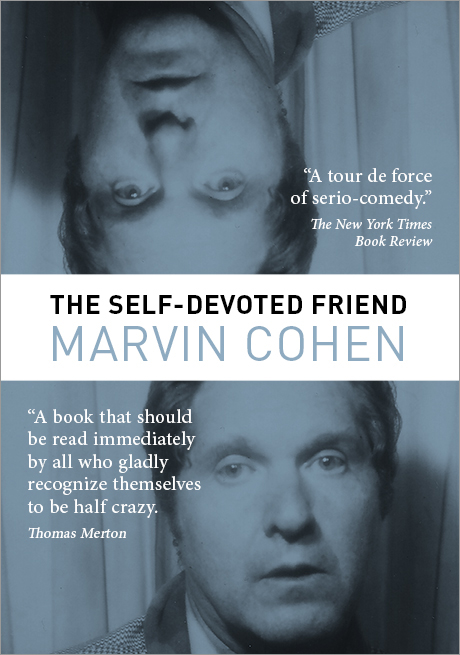

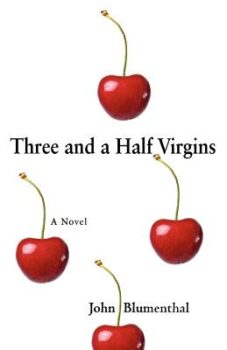

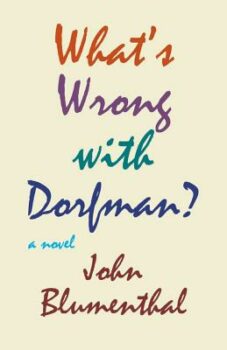

In addition to this novel, John Blumenthal is the author of seven other books, including the award-winning comic novels What’s Wrong with Dorfman?, Three and a Half Virgins, and Millard Fillmore, Mon Amour. A former Esquire staffer and Playboy magazine editor and columnist, Blumenthal has also written for television and is the co-author of the screenplays for Blue Streak and Short Time. His work has appeared in numerous print publications.

Interview:

Nina Buckless: Writing comic novels can be very challenging, but you have a natural affinity for it.

John Blumenthal: Thanks for the compliment, Nina. Wikipedia lists me as a “humorist,” and they know everything, so I feel I should live up to that. Actually, all my novels are comedic—or at least they’re supposed to be. I once tried to write a turgid Kafkaesque novel, but I can’t resist a punchline. Apparently, Kafka could. There are those who think comic novels are not serious novels. Tell that to Chaucer, Dickens, Heller, Vonnegut, among others. Tell it to Shakespeare! Humor is just a different way to tell a story. The destination is the same—the vehicle is different but it travels just as fast. (Sorry—worst metaphor ever.)

In The Strange Courtship of Abigail Bird, Ishmael Archer says, “Who knows from whence creativity springs?” Where do you find your motivation and inspiration as a novelist?

For me, motivation comes from two sources: loving to write and the idea that I can entertain readers and perhaps give them something to think about.

As for inspiration, I haven’t the slightest idea where that comes from. Does anybody? The Cosmos? Extreme boredom? An overdue electricity bill? Not a clue, although the newspapers and magazines I worked for did require me to be inspired often enough to fill pages with text on a regular basis. Does that count?

How would you describe your process of developing character arcs?

How would you describe your process of developing character arcs?

First off, I won’t even start a novel until I have a thorough grasp of the protagonist or protagonists—who they are, how they speak, how they relate to other characters, their outlooks on life, and their quirks. Frankly, I don’t know how any writer can begin to write a novel without knowing the characters. Maybe some do. I never asked.

Also, I won’t start a novel if I don’t have the voice in my head. Writing without a voice is like shooting a movie without film. (Sorry, that’s a really awful simile, but I’m too lazy to come up with another and you get the drift.)

Possibly because of my training at newspapers and magazines, I write fast and by the seat of my pants, by which I mean I don’t have a complete idea about where the story is going. I don’t do outlines; if you know exactly where you’re going, so will the reader. And most of the time I don’t know anything about the minor characters. They just kind of develop to move the story along and to illuminate aspects of the protagonist’s character. But I always create a character arc. If you’ve written 300 or so pages and the main character hasn’t grown or had a realization about himself or life, I think you’ve failed.

You mentioned hearing the voice of a character in your head, and I really enjoyed the way Ishmael Archer speaks and thinks. For me, it was part of the fun and intrigue of the book. At one point in the novel, he thinks to himself: “While I was no expert in affairs of the heart, I had learned from certain novels that love was not entirely dependent upon achievement but rather a matter of seemingly inexplicable factors.” Could this be true?

I suppose I just wanted to create a character that had, as you say, a unique, totally original voice, and Ishmael seemed like the perfect vehicle for that because of his lifelong obsession with literature. As you mentioned in your introduction, both of Ishmael’s parents are English teachers, and he starts devouring the novels at the age of six, beginning with nineteenth-century British classics. Not that this would necessarily make someone speak like a Dickens or an Austen character, but in his case, it did. Also, I love writing quirky, eccentric characters. I think his voice provides much of the humor in the book, and it also makes him sympathetic and endearing. That and his shyness and lack of social skills.

As for the second part of your question, the primary message that I’d hoped the novel would get across is Ishmael’s realization that achievement is not sufficient, or possibly even relevant, for the growth and existence of love. I’m delighted that you picked up on that. Ishmael also has an epiphany about how he has been living his life much like that of a fictional character and decides that the time has come for “Chapter One in the Life of Ishmael Archer.”

Similarly, the dialogue is part of the humor of the book, and it also helps push the momentum of the story forward.

I love writing dialogue. For me, conversational interaction between characters is the best way to define them—what they say, how they say it, and so forth. Just describing characters in the narrative works for some writers but not for me. This may strike people as shallow, but when I strum through the pages of a novel and the first forty pages are all filled with description but no dialogue, there’s a fair chance I won’t be interested in reading it.

If I’m good at writing dialogue—and in all modesty, I think I am—it probably originated from my years as a screenwriter. I’m not very good at making actual conversation with real human beings, so that’s definitely not it. Just as an aside: another thing that will make me lose interest in a novel is too much description throughout the narrative. I don’t really need to know every detail about the landscape—if it’s cloudy or what color the house is. A John Updike novel I once read had a two-page description of a tomato. Two pages! I mean, who cares? It’s reddish and it’s a vegetable.

Do you begin your novels by asking questions that you hope to answer?

Hmmm…that’s interesting. First, I ask a one very basic question: is there enough of a story here to fill at least two hundred pages? I’m not kidding. I have on occasion started novels and realized after about twenty pages that the story wouldn’t go the distance and wasn’t adaptable as a short story. I’m not interested in writing novellas, because I don’t think there’s much of a market for them and they’re difficult to sell. I don’t write for the money—I’m more interested in attracting as many readers as possible.

Hmmm…that’s interesting. First, I ask a one very basic question: is there enough of a story here to fill at least two hundred pages? I’m not kidding. I have on occasion started novels and realized after about twenty pages that the story wouldn’t go the distance and wasn’t adaptable as a short story. I’m not interested in writing novellas, because I don’t think there’s much of a market for them and they’re difficult to sell. I don’t write for the money—I’m more interested in attracting as many readers as possible.

But there are plenty of other questions, most of which concern characters, structure, voice, plot twists, and how to get across to the reader what I’m trying to say by using this story and these characters. Of course, some of the answers just turn up as happy accidents as I’m writing. As for the meaning of the novel, the moral of the story, so to speak—but not in the Aesop’s Fables sense—or the character arcs, those elements usually happen while I’m writing, especially if the book is character-driven. I have enough confidence in my ability by now to trust that this will happen. If it doesn’t happen, I think you have a book with no real point other than pure entertainment, which is fine if it’s a thriller.

Today, many people meet one another on dating apps or in online forums. For many folks, it can become an endless revolving door of unhappiness and loneliness. For some, it can lead to success or true love. In The Strange Courtship of Abigail Bird, we follow Abigail and Archer while they are courting one another. This is a novel that addresses the question of courtship. Is this a love story?

It’s definitely a love story, but kind of a bizarre one, primarily because both Ishmael and Abigail are so bashful that they kind of dance around their deepening relationship for most of the novel. Each of them has suffered emotional damage from past romantic relationships, which is one reason they are unable to express their affection for each other, but just hint at it rather ineptly. Both share a deep affection for literature, so that’s the initial basis for their attraction, but they also seem to imagine themselves to be the fictional characters they love.

You’re exactly right about online dating. People go out on a few dates but keep searching the site because they think they can do better. Upgrade, so to speak. They’re looking for the perfect mate and, of course, in some cases, they end up with nothing but regret and lonely lives.

So, as the title suggests, this book is about an actual courtship, which is a term that people don’t use much anymore. But in Jane Austen’s day, the practice of courtship was mandatory. Today, courtship starts with winking at somebody on Tinder and then texting. Ishmael and Abigail do it the old-fashioned way: they meet in person, share an interest, and find each other attractive and compatible. It’s an old-fashioned courtship because they think of themselves as nineteenth-century characters. And it’s a healthy courtship, in spite of their exasperating density. It was a challenge trying to maintain a courtship that goes around in circles for so long but there are subplots and some serious obstacles for them to overcome.

You were a student of the great poet Maxine Kumin. Do you recall any words of advice or wisdom from your days of working with her?

In college, I took a creative writing course taught by Maxine Kumin, but long after I graduated, we started a correspondence. She wrote me quite a few long letters in which she critiqued my work pretty thoroughly and very, very honestly. No punches pulled but her advice was always constructive and she was always sensitive to my feelings.

In spite of my numerous failings as a writer at that time, I was of course flattered that an author of her stature would take the time and effort to read my bungling attempts at fiction and then spend even more time typing long, thoughtful letters. Her critiques were always right on the money. It was very helpful. She enjoyed my sense of humor as it appeared in the novels but once told me that she suspected I was using humor to cover up deep emotional issues, and that I might want to explore those. She was right, of course, but I wasn’t that interested in exploring those issues. Maybe I was afraid that coming to grips with the issues would ruin the humor. For good or bad, I do believe that most humor derives from emotional issues, more than likely from childhood and early adulthood. I know what mine are but I choose to use humor as the vehicle with which to express them.

In spite of my numerous failings as a writer at that time, I was of course flattered that an author of her stature would take the time and effort to read my bungling attempts at fiction and then spend even more time typing long, thoughtful letters. Her critiques were always right on the money. It was very helpful. She enjoyed my sense of humor as it appeared in the novels but once told me that she suspected I was using humor to cover up deep emotional issues, and that I might want to explore those. She was right, of course, but I wasn’t that interested in exploring those issues. Maybe I was afraid that coming to grips with the issues would ruin the humor. For good or bad, I do believe that most humor derives from emotional issues, more than likely from childhood and early adulthood. I know what mine are but I choose to use humor as the vehicle with which to express them.

I do recall that once, after a particularly demoralizing critique, Maxine said that I should not be discouraged because I—and these were her exact words—“was so obviously a writer.” That was my very first affirmation and it was coming from an extremely successful author who did not deal in flattery. I was about twenty-four.

You have written successful screenplays. How does the process of writing a screenplay differ from that of the novel?

Ah, Hollywood. I don’t really know why I got into screenwriting. I’ve always loved movies, but who doesn’t? I thought that being in the movie business would be glamorous. (It wasn’t but it paid well.)

Regarding the differences in process, screenwriting is collaborative. Most scripts are rewritten by other screenwriters or directors five or ten times. Scripts have a different format and they’re divided into three acts. Unlike novels, descriptions of characters have to be kept short and the concentration is on plot and action. Mandatory length for most commercial high concept comedies is no more than 120 pages, but most are about ninety-five. The first act usually has to end between pages fifteen to nineteen. Plot twists occur after every act. There are all kinds of constraints like those. That was one reason why I quit that career. A lot of people think screenwriting is easy. It’s not.

What have you been working on lately?

Since Covid19, I’ve been writing semi-serious opinion pieces for newspapers like the NY Daily News, Chicago Sun-Times, Cleveland Plain-Dealer, but that’s not really journalism in the strict sense. Most are about the Pandemic or Trump. It’s a hobby.

A good hobby to have. We are in the middle of one of the worst pandemics in over a century, and the nation is politically divided. Has the role or the responsibility of the fiction writer changed in any way?

I don’t see how these events will have any profound effect on writing or on writers’ roles. I don’t think Jeffrey Eugenides is suddenly going to write like Theodore Dreiser. God help us if he does. Writing styles change with the language of the day, but people are still people and stories are still stories. That’s not going to change. Take the two World Wars—I don’t think Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead was all that different from Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Events provide a backdrop, but they take a back seat to stories and characters. Any future novel that takes place during the Pandemic will still need to have the same elements that any good novel from any era contains: good sympathetic characters and stories.