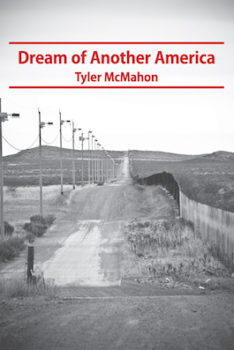

Tyler McMahon’s sweltering train-hop of a third novel, Dream of Another America (Gival Press), is set along the treacherous human-smuggling route from Central America to the United States and is the story of Jacinto, an unpapered economic refugee from El Salvador.

In El Salvador, Jacinto and his wife are happy to farm their small parcel of land, but when their son comes down with a severe respiratory illness whose treatment is financially untenable, Jacinto’s neighbors say that the solution to his economic woes lies in the North. In America, Jacinto hears, one can earn more in a single week than in a full year of growing beans and corn in their native land.

With a heavy heart, Jacinto hires a “coyote” to smuggle him into America and sets upon the overland journey through Mexico, toward the reputed northern fortunes that could help to save his son’s life. In Jacinto’s absence, his wife and child must fight their own battle against an unscrupulous trafficker who demands additional payment, even though Jacinto’s journey has been met with peril.

Dream of Another America is the story that lives in the shadows of our headlines on immigration and is saturated by an aerosol of common bandits, cops on the take, and those particularly shameless purveyors of the foul who capitalize on the desperation of the poor.

Tyler McMahon has crafted a scorching allegory for our time, and the narrative of Dream of Another America, that of the impoverished and their lost, haphazard hustle toward a so-called promised land, should give cause for a deep disruption to the American conscience.

Interview:

Reuben Appelman: Your first two novels, How the Mistakes Were Made and Kilometer 99, both feel like novels about the underclasses or, at least to a degree, novels about the dream to create something out of nothing, which seems like the so-called American Dream. Do you think that’s an accurate assessment of those books?

Tyler McMahon: I never thought of it in quite those terms, but it does strike me as accurate. In my first two books, the characters were both chasing after something bigger—fame and success in one, seeing the world in the other. But, in both cases, it had to do with elevating their lives to meet their own expectations. Certainly, that is a part of the American Dream.

In many ways, the American Dream mythology is really just a mythology of nationalism, which is to say that, regardless of how much I might love my country—and I do— the American Dream is a propaganda flyer. We do have an amazing quality of life for those who can afford it and, even for those who can’t afford it, our basic shelter-related needs are mostly being met. It’s an incredible country, but Dream of Another America seems to hit on the idea that there’s a blind spot in how we view it. Can you talk a little about that?

I believe in the sentiments behind the American Dream: in social mobility, in meritocracy. It’s a powerful notion, in the broader historical context. But, it assumes that everyone starts on a level playing field. It assumes that there are infinite jobs and resources available for whoever is willing to go out and take them. These assumptions are naive at best. At their worst, they are dangerous; they offer a moral license for judging our less fortunate neighbors.

Where do you get this impulse to speak from what’s likely the center of what I’ll now call the American dilemma?

The impulse behind this new novel was to show how much the immigration experience resembled our most beloved stories and myths. I was thinking about books like The Road and Cold Mountain, or, more obviously, Grapes of Wrath and the Odyssey. These are all stories of individuals making long journeys through inhospitable landscapes in order to keep their families together, often with a memory of war lurking in the background. So much of our literature has taught us to empathize with this sort of plight, and yet, somehow, we seem to be going in the other direction. It seems odd to me that so few contemporary novels have applied this classic story structure to a journey that now happens every day, such as with the refugees fleeing conflicts in Syria or Afghanistan.

The impulse behind this new novel was to show how much the immigration experience resembled our most beloved stories and myths. I was thinking about books like The Road and Cold Mountain, or, more obviously, Grapes of Wrath and the Odyssey. These are all stories of individuals making long journeys through inhospitable landscapes in order to keep their families together, often with a memory of war lurking in the background. So much of our literature has taught us to empathize with this sort of plight, and yet, somehow, we seem to be going in the other direction. It seems odd to me that so few contemporary novels have applied this classic story structure to a journey that now happens every day, such as with the refugees fleeing conflicts in Syria or Afghanistan.

We have a presidential administration in America that would like to curb the influx of immigrants, which essentially means curbing an influx of the impoverished. I’ve seen eight presidents and none has been as rough on the underserved, disenfranchised, and lost. That’s not a judgement, just something that appears to be fact—and the administration has many millions of supporters. Whether or not the president won with the help of Russians infusing social media with propaganda is only partially relevant. At the end of the day, people bought that propaganda and voted with their hearts, which seemed to be exclusionary in nature. Did Dream of Another America come out of the sense that our country was moving in this direction?

The president’s ideas simply don’t reflect the facts. Immigration has been in decline since the late nineties. All the data shows that undocumented immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than native-born citizens. Most importantly, our country has very low unemployment at the moment. So, the idea of anybody coming here to take away jobs is a bit of a fallacy. And now that we’ve committed to an economic policy based on growth at all costs, it’s unclear to me who would be available to take all those new jobs, were they to actually be created.

But the most shocking thing about the president’s rhetoric has been its reception. As you said, many millions of Americans responded to it, Russian bots notwithstanding. This has taken me by surprise. I had believed that the ubiquity of Latin Americans—citizens and residents—in the US would change our politics and our attitudes for the better, that it would make us less xenophobic, not more. It appears that I was naive.

So, I can’t say that I sensed the country moving in this direction. Frankly, I’m shocked and saddened that this novel is as relevant as it is.

Which is additionally surprising because even though there might be an overall immigration decline, Hispanics like your character now make up the largest minority population in many of our major cities and, in some areas, appear to be in the majority—and not just in low wage positions like the construction labor forces of Austin, Texas or Los Angeles, or the farm labor forces in the Midwest and West, but in the business world, in politics, and in the media. So, it’s crazy to think that this massive population of people who are now so widely accepted by so many as integral to the structuring of our society are also so widely shoved-aside. I won’t ask you to try to explain racism but how does Dream of Another America tackle this bipolarity of the American consciousness?

It is crazy. This is part of that unpleasant surprise I mentioned. In my childhood, I tended to think of “immigration” as a coastal, urban phenomenon: big cosmopolitan cities, people from many nations and ethnicities, unfamiliar languages and foods. It’s not hard to see how rural America might find that stereotype threatening or overwhelming, on its surface.

But while working for the Peace Corp in El Salvador, I realized that this stereotype isn’t so accurate. The truth is that rural Salvadorans often move to rural America. They are farmers, by and large, and they share the values of Middle America: hard work, thrift, religion, family. Their presence has been a net positive for those small towns in the States; it’s been a massive boon for business owners.

Not so many years ago, I was sure that Salvadorans like Jacinto would move the needle, politically, that they would help break down the urban and rural divide that seems to determine how Americans feel about immigration. But, again, it appears that I may have underestimated the extent of our xenophobia.

Can you talk about Jacinto’s journey a little, and also about the problems he left back home for others in the wake of his departure?

Jacinto is a sort of composite of many Salvadoran men I knew during my time in El Salvador. He survived a brutal civil war—a proxy war between superpowers, really—only to be granted a small parcel of farmland after the Peace Accords. Like many campesinos, he was happy enough to get by with subsistence farming. But that lifestyle becomes untenable when his son, Wilmer, develops asthma. Jacinto and his wife, Mina, have to make a decision. Reluctantly, Jacinto pays a smuggler for passage north to the US.

Jacinto is a sort of composite of many Salvadoran men I knew during my time in El Salvador. He survived a brutal civil war—a proxy war between superpowers, really—only to be granted a small parcel of farmland after the Peace Accords. Like many campesinos, he was happy enough to get by with subsistence farming. But that lifestyle becomes untenable when his son, Wilmer, develops asthma. Jacinto and his wife, Mina, have to make a decision. Reluctantly, Jacinto pays a smuggler for passage north to the US.

Along the border, Jacinto’s party is left for dead in the desert. The sole survivor, Jacinto is sent to the Guatemalan border. From there, he undertakes the journey on his own, without the smuggler’s help. Hungry, penniless, and disoriented, he finds his way across one foreign country in order to sneak into another.

At home, Mina and Wilmer face their own challenges. The smuggler claims that Jacinto died along with the others in the desert, and demands payment in full. They struggle to keep him at bay, and to divine Jacinto’s actual whereabouts.

How much of your protagonists’ plight did you model on research or current events and how much did you come to intuitively?

The parts of the book that take place on the home front—Wilmer and Mina in their small village —are mostly based on things that I saw or experienced in El Salvador. I can vividly recall the terrible anticipation that families would go through when they didn’t hear from their respective travelers. It was always a major source of gossip and speculation around the village.

Jacinto’s adventure drew heavily from several sources. His ordeal in the desert was inspired by the actual incident that Luis Alberto Urrea describes in his amazing investigative nonfiction book The Devil’s Highway. Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario was extremely helpful when writing about the train hopping that occurs in southern Mexico. A lot of the southwestern fruit-picking chapters were inspired by Coyotes by Ted Conover. Crossing Over by Rubén Martínez and Lives on the Line by Miriam Davidson were also very helpful.

As a novelist, my favorite fictional conceit is simply to shove a lot of things into one character’s life. In the case of Jacinto, I made him experience virtually all of the anecdotes I’d read about or heard of—from all over Mexico and the American West. That seemed a better way to use the tools of a fiction writer, to distinguish my book from all the great journalism and reportage that had inspired it. A lot of the outlining and plotting of the story was a matter of getting Jacinto from one place to another, and sometimes back again.

Medical care in America is among the best in the world, but the choke points are numerous. Poor people in studio apartments are dying in the shadows of billion dollar, high-rise hospital wings. Were there related issues you were attempting to tackle in the novel?

What interests me about the healthcare crisis in America is the way that it relates to our faith in the free market. I’m not a full-blown socialist, and I appreciate all that the American economy has done for me. The profit motive is great for making cars and cell phones, perhaps even for space travel. But in the case of healthcare, it’s abundantly obvious that there is no room for market-based approaches. All the international comparisons tell us this, and decades of failure here in the U.S. corroborate it. Our inability to address this problem is a defeat of reason at the hands of free-market ideology.

In terms of my novel, this plays out in the need for earning cash, no matter who you are. For generations, hard-working subsistence farmers, like my characters, were able to raise their own food, build their own houses, and sew their own clothes and the like. But now, if you want to keep your family healthy, you’ll eventually need insurance or wealth. As much as we may fetishize it, “living off the land” is effectively an anachronism. There is no amount of belt-tightening or self-sufficiency that would’ve allowed Jacinto to medicate his son. It was in another orbit, financially.

Also, the healthcare crisis brings up questions of greatness, and how we measure it. Does it mean anything to have the best doctors and hospitals and medical devices in the world, if only a privileged few are able to access it? The question applies equally to education.

In all three of your novels, the details of place and experience are vivid, and the characters all really seem to intuit all of that in a way that real people who have been to a real place just sort of do. Meaning, if I’m from Detroit, I walk and think a certain way, and that’s hard to mimic in writing if you aren’t also from Detroit. In your books, you’re right up front in the weeds of a place as if it’s your own, and it feels very real. Can you speak to this?

In all three of your novels, the details of place and experience are vivid, and the characters all really seem to intuit all of that in a way that real people who have been to a real place just sort of do. Meaning, if I’m from Detroit, I walk and think a certain way, and that’s hard to mimic in writing if you aren’t also from Detroit. In your books, you’re right up front in the weeds of a place as if it’s your own, and it feels very real. Can you speak to this?

It’s interesting—and flattering—that you put it that way. In so many ways, I feel like I do not write about my own life very much. Certainly, that’s never the starting point. For so much of my youth, I felt that I’d come from an unremarkable place: somewhere that wasn’t quite the city and wasn’t quite the country, not quite the north but not quite the south either.

For instance, I was born in Washington, DC in 1976. I grew up in northern Virginia, basically the outermost suburbs of DC. My experience with the DC punk scene has been greatly exaggerated because of the content of my first novel [How the Mistakes Were Made]. In actuality, by the time I had a driver’s license, the DC hardcore icons had all disbanded. They did, however, cast a long shadow over much of my generation. In an age when most pop culture was controlled by major corporations, that DIY movement taught important lessons about integrity and authenticity. While I played in bands in high school, I’m no real musician or punk rock insider. I wrote about that form the sidelines, really.

Other places, like El Salvador, made a stronger impression. I get a lot of inspiration from texts—from articles or reportage or documentary films. But I always seem to synthesize it with places and people that are close to me. As you say, it is mostly a matter of making the details real, so that the story feels tangible, and believable.

And yet, I also would worry about putting too much emphasis on familiar places and experiences. For me, particularly in the past few years, the joy of writing a novel is really a matter of disappearing into another character for a while. In fact, when I was an MFA student, one of the most important lessons I learned was to take more liberties, to stray further from the facts as I knew or remembered them. So, maybe it’s a matter of micro-level accuracy, as opposed to macro-level accuracy.

Can you tell me about your Peace Corp experience and how it informed your work?

I signed up for the Peace Corps when I graduated from college, and was sent to El Salvador a few months later. I went as a water and sanitation volunteer, and was assigned to a set of small villages that lacked a potable water source. Most of my time was spent working on a gravity-fed aqueduct that would eventually bring running water to those households.

Peace Corps is a decentralized organization, so I don’t want to speak for anybody else’s experience. But, for me, it was a great time. We had a terrific staff that was supportive but also gave us latitude to work and live how we liked. The country was small enough that I made many good friends among the other volunteers. I became very close to one of the families in the village, and spent most evenings with them.

Looking back, I feel even more fortunate to have gone to El Salvador when I did. They’d only opened the country back up in 1993, after the long civil war. They suspended operations again in 2006, citing gangs and other concerns. I was lucky enough to serve during the thirteen-year window when things were safe enough for the Peace Corps to continue its work.

Nowadays, I imagine most volunteers have cell phones and Internet. I’m grateful that my time was just before that change. It was the perfect fit for me, in my early twenties. It was a good counterweight to my university education, and taught me everything I know about working with people.

In addition to informing my work on Dream of Another America, El Salvador is also where I learned to surf, and why I eventually developed the characters in Kilometer 99. There are great waves in El Salvador and my village wasn’t too far from the beach. In those days, there were very few tourists, and the expat surfers that came through were a pretty adventurous bunch. Many were on long trips through Central and South America, dropouts who were stretching their money. Growing up on the east coast, I had rarely met people who had so fully disabused themselves of career-centric values.

In addition to informing my work on Dream of Another America, El Salvador is also where I learned to surf, and why I eventually developed the characters in Kilometer 99. There are great waves in El Salvador and my village wasn’t too far from the beach. In those days, there were very few tourists, and the expat surfers that came through were a pretty adventurous bunch. Many were on long trips through Central and South America, dropouts who were stretching their money. Growing up on the east coast, I had rarely met people who had so fully disabused themselves of career-centric values.

Things are different now. El Salvador has become a high-priced surf destination.

Speaking of the characters in Kilometer 99, did you intuit them from the same place of intuiting Jacinto, or do you arrive at different characters from different parts of your soul?

That’s a good question. When I think up a character for a novel, I’m often trying to make one person live through several aspects of a given thing. In my first book, How the Mistakes were Made, the narrator experiences both a scrappy underground scene and chart-topping fame—while playing essentially the same music. Jacinto, as I’ve said, lives through almost all of the immigration anecdotes that I’d heard or read about. Much of the book’s architecture was a matter of moving him around so that he can go through those ordeals.

I’m almost always trying to create characters who are at a crossroads, torn between going and staying, between accepting this life or aspiring to another. There’s something of that in all my characters, and I’ve often wondered why I do this. It’s definitely more about instinct than intention. There’s just something suspicious about anyone who feels too certain—about their goals or their ideology or anything else.

Feeling conflicted is, I suppose, part of the human condition.