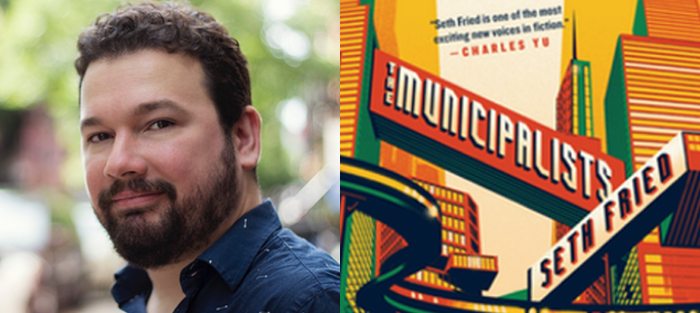

The Municipalists, Seth Fried’s debut novel, opens on the death of the narrator’s parents, progresses into a terrorist plot that threatens the cultural institutions of a major city, and questions the systematic lack of support for poor urban neighborhoods. Yet you’d be hard-pressed to not call it a comedy. The narrator, Henry, is a square enamored with bureaucracy, an urban planning paper-pusher with “a reputation as the biggest milquetoast bean sorter in the history of the United States Municipal Survey.” His love of the system and its rules stems from how it looked after him in his orphaned childhood: even when caretakers didn’t like the government, “the rules always stayed rigidly devoted to [his] well-being.” When Henry’s employer, the United States Municipal Survey, is hacked, Henry is sent to the city of Metropolis to investigate and partnered with OWEN—a blue-eyed, vain, eccentric, and noir-inspired projection of a supercomputer who’s prone to dampening his systems with alcohol protocols, and who tends to solve problems with projected samurai swords and SWAT teams. To defeat the architect of the plot, OWEN has to navigate humanity’s quirks and Henry has to break the rules.

The elements and themes of Fried’s debut collection, The Great Frustration (Soft Skull Press), are here in The Municipalists (Penguin Books). There’s scientists and other intellectuals, dark suits, and patriarchal figures; and there’s shame, awkwardness, and frustration. But while the collection consisted of fictions in the style of Italo Calvino and Steven Millhauser, and mainly used descriptive summaries to track the evolution of ideas, The Municipalists takes those recurring elements and spins them into plot points. The novel is a fun, fast-paced story, chock full of heartfelt and hilarious dialogue, compelling characters, and slapstick action. It showcases a new side to Fried’s fiction, and it feels like a natural, welcome expansion of his already considerable skills.

Fried is a recurring contributor to The New Yorker’s “Shouts and Murmurs” and NPR’s “Selected Shorts.” His stories have appeared in Tin House, One Story, Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Kenyon Review, and others. This interview was conducted via facsimiles sent from the New York office of the United States Municipal Survey to the Department of Revenue in Fort Smith, Arkansas. I myself have not visited in many years, but the New York office is said to be more resplendent than ever.

Interview:

Shawn Mitchell: Rate your work-life-creativity balance on a scale of 10. Explain.

Seth Fried: I’m pretty lucky in that I get to teach creative writing when I’m not writing myself, so on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 being not very creative and 10 being whoa that’s TOO creative) my day-to-day balance is a strong 10. Getting to work with students on their stories is not only fun, but also a great way to get out of my own head while still staying engaged with the creative work that’s important to me.

Do you run a more-or-less “traditional” workshop (literary short stories, roundtable discussions, and so on), or do you incorporate other elements? Basically, what do you teach, and what’s your approach?

It’s mostly a traditional workshop. I do some craft lectures and we discuss student work as a group. My approach is to find out what a student is excited about in their writing, what their proclivities and abilities are, and then to encourage them to quadruple down on those things. My experience as a writer and as a teacher is that if you encourage someone to go deep with what they love about their work, you’ll be fanning a flame that will end up burning up all their other problems as a writer. I definitely try to give people tools and tips to help them avoid common pitfalls, but all craft is connected so I find that if you can help someone push the things they’re already doing well, they’ll naturally start uncovering other craft skills on their own. And when someone stumbles across a craft element in their own draft, I think they end up owning it in a way that they never do when it’s presented in a dry lecture. In fact, most of the writers I work with tend to get prickly when presented with craft principles. No matter how much you encourage them to take your lectures with a grain of salt, they’ll still tend to interpret any principle of craft as an assault on their creativity. Craft lectures are important, because there is the occasional writer who can internalize that information to the point where they can use it in their work. But for the most part my approach is more about figuring out what people want to do with their writing and helping them at the process level so they can keep doing it.

In “Animalcula: A Young Scientist’s Guide to New Creatures” in your debut story collection, The Great Frustration, you describe a series of fictional microscopic creatures with a range of extreme characteristics, one of which is the kirklin:

All kirklin currently occupy a space no larger than an acorn. This arrangement should be impossible, as there are currently ninety-five trillion kirklin in existence, and each is roughly the size of a grain of rice.

Kirklin is also the name of the Metropolis station chief in The Municipalists. Kirklin is responsible for making the city operate efficiently and catering to the needs of its many people, and the novel’s escalating plot caters to the kirklin’s source of fascination, the “potential force” of that compression and “the natural human fear of catastrophe, the perpetual concern that the sky will fall.” Am I right in being a smart, good boy and reading that as a self-reference? And which animalcula would you say Henry, OWEN, Sarah, and Garrett align with and why?

This question is amazing. If anyone else asks, I’ll probably use your thoughtful analysis to make myself look good. But really this just speaks to the fact that I suck at coming up with proper nouns. My wife has pointed out that whenever I try to do surnames in early drafts I tend to just smash two nouns together (Nunthrow, Sipspit, Crampcough). In subsequent drafts I will replace those names with more human-sounding ones. For whatever reason I find the process arduous and unrewarding. I remembered the name Kirklin from that piece and it just sounded right to me for that character. If there was any reasoning beyond that then it was being done by a part of my brain to which I don’t have direct access.

This question is amazing. If anyone else asks, I’ll probably use your thoughtful analysis to make myself look good. But really this just speaks to the fact that I suck at coming up with proper nouns. My wife has pointed out that whenever I try to do surnames in early drafts I tend to just smash two nouns together (Nunthrow, Sipspit, Crampcough). In subsequent drafts I will replace those names with more human-sounding ones. For whatever reason I find the process arduous and unrewarding. I remembered the name Kirklin from that piece and it just sounded right to me for that character. If there was any reasoning beyond that then it was being done by a part of my brain to which I don’t have direct access.

But pairing the characters up after the fact, I’d say that Henry is a melite, which is constantly trying to repair a formative trauma. OWEN would probably be a cross between an eldrit (also the name of a hotel in The Municipalists because of my aforementioned name laziness) and a kessel. The eldrit is a compulsive shapeshifter and embraces change as its only constant, which speaks to OWEN’s role as a trickster. However, OWEN also has a deep authenticity that connects it to the kessel’s ability to forge urgent emotional bonds. In Sarah Laury, we have the unwavering ideology of a lasar and the lonely one-of-a-kindness of an adornus. Garrett is like a scientist studying a sonitum, but he has lost the courage to shout. To understand all these references, The Great Frustration is available for the low, low price of $15.95.

Speaking of trillions of creatures compressed into a space the size of an acorn, I moved from Missouri to Brooklyn and lived there for a few years but left to get my MFA in Illinois. I’ve bounced around since then from Korea to Kansas City to, now, Arkansas. I enjoyed living in New York, but I’ve never had a strong urge to move back. You moved there from Ohio and have stayed for eight years, and Metropolis is a fictionalized New York. What drives you to stay, and what drew you to writing about New York and cities in general in The Municipalists?

In my late twenties I was in Toledo, Ohio, living on people’s couches. I couldn’t get a job anywhere and I wasn’t being a snob about it. I applied to Waffle House where the application was a postcard that asked for your address and if you had ever been convicted of a felony. I never got a call from them, which made me wonder if I had answered the felony question correctly. It was tough.

So when I got the small advance for my first book, I bought a plane ticket to NYC, moved into a one-room apartment in Bay Ridge that I shared with four people, and almost immediately got an entry level job where I got to sit at a desk and drink free coffee. It was technically an internship, so I think I was making like $10.00 an hour, but it was amazing to me. Right away I had to wonder how a person who hadn’t even been able to get an interview at Waffle House was now drinking free coffee in a high-rise in Manhattan.

People point out that New York can be a hard place to live and it is. But when you’ve spent your whole life being poor in the Rust Belt, the challenges that New York has to offer feel downright generous. The whole experience was immediately much more humanizing than the decades I spent grappling with my poverty in Ohio.

That said, I do have a tendency to look at the city with a bit too much optimism because of my personal experience. Not everyone is as lucky or as privileged as I am. After all, a white, straight, cisgender man is still benefitting from a lot of privilege even if he’s poor. So while New York was a thrilling and transformative place, it felt important to educate myself on how it was failing others. The Municipalists was a way for me to dig deeper into the idea of cities in general, both to explore the ways in which they can be great and to come to a better understanding of how they need to change.

You interviewed Christopher Bollen for The Nervous Breakdown back when you were fresher to the city. Now that you’ve been there a while and have written a novel that explores it, please answer your own question: “Was it difficult to write about a living, breathing city? Does all the craziness of being here get easier to articulate the longer you’ve been here?”

I think it comes down to the same advice I would now give anyone approaching a big topic in a story. That advice is to lean into your characters in order to give that topic a sense of focus. In the end, I couldn’t write about a whole city because that’s one of those tasks that gets more absurd the more you think about it. Any book claiming to do that would only be able to get there by denying its ignorance of a city’s true complexity. But it was possible for me to write about a city seen through the eyes of a guy who was awkward as I am and who was grappling with the same thoughts about cities that I was.

It’s clear how New York plays into your fiction, especially in The Municipalists, but your earlier stories bounced around in terms of setting and subject and only touched on the Midwest a bit in “Lie Down and Die” and maybe “Frost Mountain Picnic Massacre” and “The Frenchman” (I don’t remember the towns in those latter two being named, but some other cities in the region come up and they feel pretty Midwestern). How do you think growing up without enough money in Ohio influences your writing and creative life, if at all?

It’s clear how New York plays into your fiction, especially in The Municipalists, but your earlier stories bounced around in terms of setting and subject and only touched on the Midwest a bit in “Lie Down and Die” and maybe “Frost Mountain Picnic Massacre” and “The Frenchman” (I don’t remember the towns in those latter two being named, but some other cities in the region come up and they feel pretty Midwestern). How do you think growing up without enough money in Ohio influences your writing and creative life, if at all?

I think the influence of where you were raised is always pretty undeniable. I’d been trying to escape the Midwest mentally many years before I ever actually left. In my first book, I embraced fabulism because it seemed like a rejection of place in fiction. But looking back on The Great Frustration, the Midwestness of all the stories you mentioned is pretty obvious. And that bothers me a lot less now than it might have if I had realized it when I was writing them. One of my heroes is Italo Calvino, and in Hermit in Paris he wrote about how he needed to be in Paris in order to have enough perspective to write about his hometown in Italy. Similarly, I’ve actually started writing about the Midwest a bit more overtly in recent years. The first piece I worked on after The Municipalists was a story called “Mendelssohn” for Tin House, which is hands down the most Midwestern thing I’ve ever written. Though it’s more idealized than my lived experience. I’ve also just finished another piece that’s specifically about growing up poor in Ohio. I feel like all that experience has finally become usable for me because it’s so far away both geographically and in time.

When The Great Frustration was forthcoming, you told the Kenyon Review that you used to feel pressured to work on novels instead of short stories for the purpose of sellability and that you wasted energy on projects you didn’t care about because of that. What was different about The Municipalists that didn’t make you miserable like those earlier projects did? Were there any moments that began to feel miserable, and if so, how did you get through them?

I think the main difference is that I met my wife. She’s the most impressive person I’ve ever met in a lot of ways and one way is that when it comes to projects she’s completely unafraid. If she wants a certain kind of bookshelf, she builds it. If she likes a song, she learns to play it. If a book is written in a language she doesn’t know (this is a real description of observed behavior), she immediately starts scanning the page for words that look familiar. When you live with a person like that and you have an idea for a novel that you’d be excited to read, let alone write, you don’t panic or retreat into your cobbled-together identity as a short story writer. You just start drafting.

There were plenty of times when the project felt miserable, but I think that’s true of any project where you’re pushing past your upper limits. Your job as a writer in those moments is to use that miserable feeling to get you to dig deeper into your own interests and passions. You have to find something that will get you excited again.

My partner seems to be able to learn anything like that. We moved here for her family medicine residency, but she hasn’t started yet and she’s been spending her free time pursuing various creative projects. When we were in KC, she taught herself how to conlang so she could have a realistic language for a fantasy novel she was drafting, and since we got here she’s taught herself the basics of woodworking. I’m just not like that, I don’t think. Writing is pretty much my only marketable skillset. Are you able to and do you delve into any other creative areas like your wife?

Oh, I’m absolutely the same way. If writing weren’t a thing, I would basically be a paper weight that needs to be fed.

In your interview at The Qwillery, you said that Italo Calvino’s notion of lightness in Six Memos for the Next Millennium, his collection of lectures on the key tenets of his writing and the literature he preferred, framed your work on the novel. Calvino describes lightness as a “subtraction of weight,” from people, heavenly bodies, cities, story structure, and language. Can you give some examples of where this informed your drafting and editing? Did the city ever start to become oppressively heavy, or the language or characters or direction of the plot? Essentially, what did you have to do or change to make the story have the right balance of heft and lightness?

Subtraction has always been a big part of my process. In his Paris Review interview, Stanley Elkin claimed that all writers are either putter-inners or taker-outers. I always wanted to be putter-inner and for a long time that’s how I saw myself, but it turns out I’m much more of a taker-outer. I will write a very long, messy first draft, which ends up being raw material that I need to make work through refinement and subtraction.

I also try to embrace lightness at the macro level as well. There’s enough fascinating information about cities to fill thousands of pages. But in valuing lightness I wanted to see how much I could get in while telling one clean story arc. Pretending that any piece of writing could truly exhaust a subject has never been an attractive delusion to me. When I’m choosing books to read, I want an author with an eye who has curated her material. I want a handful of gems I can slip into my pocket, not a massive pile of gold I need to figure out how to get across town. When I’m working on a project of my own, that’s still what I’m aiming for.

How did you define and clarify your world-building for elements like OWEN’s technology? Did you ever get deep into researching the particulars of how he could work? Did you get hung up on anything about it, and if so, how did you fix it and move on? I’m asking because I sometimes feel unsure about my world-building and the technology in my stories. I have to sit and define it and then revise with that definition in mind in a later draft.

When it comes to fantastic elements in a story, I’m usually more interested in if the world has an explanation for that element than the details of what that explanation is. If the main character walks in with a flaming sword, I want to know if the sword is magic or a piece of technology or if no one knows one way or the other. Beyond that my interest tends to dip. I want to know how that sword will be interpreted by the other characters in the scene and to what extent our main character will be able to control it, because those are the only wrinkles that I see having a meaningful impact on the story.

I’m in the process of pitching a novel to agents on which I’ve been working off and on for seven or so years. I’m worried that if and when I get edits I’ll be so tired of the book that it’ll be hard to work through them. You said over at One Story that you sometimes respond to feedback too quickly with defensive stances and have learned to wait and try to perform the edit or reach a compromise. What was the editing process like for the novel? Were there moments where you passionately saw it one way and someone else saw something different? If so, how did you process that feedback?

First of all, congratulations on being about to wrap up your novel! That’s exciting.

I really lucked out in that both my agent and editor had wonderful notes that were really fun to work on. Something I’ve learned as a writer since that One Story interview is that you have to consider the note in a larger context. Young me was seeing each individual note as a zero-sum decision, when that’s not really how it works. You might be getting a note that’s directed at one part of the story, but if you give it some thought you’ll realize that actually the problem is introduced much earlier in the piece and is a much simpler fix.

The example I give to my students is this: imagine I keep showing up late for work, so my boss tells me that I need to get a more reliable car. But I’m more familiar with my whole morning routine, so I know that the actual problem is that I just don’t know how to tie my shoes.

That said, edits will always be at least a little bit uncomfortable. So my old advice definitely still stands. Give yourself time to process the emotional dimension of the edits before throwing yourself into the work of responding to them.

Also in your interview at The Qwillery, you said you’re finishing a new story collection and working on a new novel. How has your work on the novels changed your approach to or the style of your short stories, if at all? And do you think the next novel will be more experimental like your short stories, or another more traditional narrative romp like The Municipalists?

The collection will be as weird as I can make it. A lot of the pieces in my first book were more fictions than traditional stories (with characters, plots, etc.) and the novel has definitely turned me on to the fun of working with story. So that might be the biggest difference in this new collection. The long pieces will have a stronger sense of character and situation. But I think that will give a nice layer of texture to the book, since the shorter stuff will still just be pure fiction.

I’m less interested in writing a novel without a sense of story. But I would love to write one with more of an emphasis on my characters’ interiority. Since The Municipalists was focused on the impact of built environments, the resulting story was largely external.

Outside of something that is fictional but does not have a plot or main characters, what do you consider a fiction? And what makes a compelling one?

A fiction is great in that in can be absolutely anything. But that’s also the scary thing about trying to write one as opposed to a story. One of the weirdest paradoxes of creative work is that constraints tend to be more fun than total freedom. My first book ends with a collection of fictions that we’ve already talked about, Animalcula. Each section is a description of a microscopic creature that doesn’t exist. These were idea-driven pieces and my rule for making them compelling was that the original thought that prompted me to start writing the piece had to change or become more complicated by the time I was done writing it. My reasoning was the same as that Frost quote, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” If you’re ever working on something outside the existing structures of story, you can always lean into your ideal reader like that. Whenever you get lost, just try to imagine what would get that reader excited.

I’m trying to wrap up this novel and get back into a looser and more playful drafting state after a lot of time spent revising and editing. Do you have any advice for someone who is exploring what to do next after finishing up a long project?

Here are some of my favorite tips for getting back into the generative zone:

1. Use a physical activity to brainstorm. Take a notebook for a walk or to the gym or keep it in your back pocket while you’re working in the yard. Nothing can kill the early generative stage more than sitting down where you draft and forcing yourself to concentrate. Creative ideas come from relaxing your sense of focus, so do something that will get you out of your head.

2. There is a toy called Rory’s Story Cubes. They are absolutely for children, but I think they’re fantastic. I’ve gotten tons of story ideas from them. You can buy them as physical dice or as an app on your phone. This is not a paid endorsement. I just love them.

3. Get a cheap, distraction-free word processor. I recommend the Alphasmart Neo 2. They don’t make them anymore, but you can find them used online for like $30.

4. Play some improv games with your friends, if they’ll let you. My wife and I will often play Would You Rather, in which you try to present someone you know with a difficult dilemma (“Would you rather do too much LSD or go on a Carnival Cruise?”). This game can really help you flex your story writing muscles, since you’re using your observations about that person to help you come up with situations that would be equally unappealing to them. That mechanic alone is a huge component of story.

5. Let everything you do in this stage be messy and bad. There is a magic to that messiness that can’t be recreated later on in the process.

To bring it home, then, would you rather visit the Frost Mountain Picnic or spend the rest of your life as a scientist studying (yelling at) sonita and unable to write?

I feel like we’ve all been living inside the Frost Mountain Picnic for the last few years and it’s about as terrifying and frustrating as I imagined it. But I’m surprised to find that there’s a lot of hope and goodwill in here too, if you know where to look. So I think I’ll stay put.