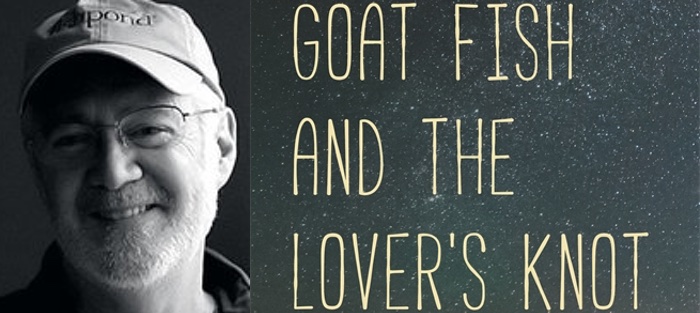

I’ve been thinking about my friend and teacher Jack Driscoll a lot this year, even before I read his stunning new collection, The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot (Wayne State University Press). I’ve known Jack since I was sixteen, and though I don’t get to see him very often (I live in southern Virginia, he in northern Michigan), he’s become one of the touchstones of my writing life. Long before I experienced it for myself, I learned from Jack’s example that being a writer was more than what you did at your desk. It required not only dedication and what Jack calls a “hard core work ethic,” but also kindness, respect (for both people in the real world and the people you invented), a sense of humor, humility in the face of disappointment, and love and enthusiasm for language to keep you going through dark days. These are qualities that I—and our world in general—seem more in need of now than ever.

The ten stories in The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot come from the pen of a writer who always tells the truth, but also understands that truth is more than just cobwebs and dark places. Though his characters are down on their luck in some ways, they look to the future with a hopefulness and sense of grace that seems to light the world beyond the page.

Interview:

Mary Stewart Atwell: We live in a time when some politicians and much of the media take it as a given that intellectuals and artists don’t care about working people. You’ve spent most of your career following the lives of disadvantaged people in rural northern Michigan, where you’ve lived for many years. (And, as you mentioned in our other interview, you yourself grew up in a blue-collar household in Massachusetts.)

How do you respond to the current political climate, and in particular, to the idea that people who think and write for a living are out of touch with real America?

Jack Driscoll: When it comes to technology I have little interest and even less aptitude, and that’s a challenging, if not menacing combination in today’s techno-world. I can’t remember who referred to “the no place of cyberspace,” but it’s exactly how I feel, and so I avoid it like the plague. I write on a computer that’s not even connected to the internet and I still have a flip phone, which I use only when I travel. I opened my Verizon bill this month and saw that I’d used a total of thirty-seven seconds. I spend virtually no time online, nor in front of the TV, and although I’m not unaware of the dramatically shifting and dispiriting political landscape, it hasn’t, as far as I can tell, affected my writing. Except, perhaps, to make me want to spend even more time inside my stories.

I wonder if most politicians claiming to represent “working people” understand much, if anything, about them. One thing I’m certain of is that when the doomsday ship pulls in, the disenfranchised will not be the first to board. I also wonder how many politicians ever read, or ever have read, serious literature, where the uncorrupted truth about character and the human heart is revealed.

My father worked 364 days a year, sixteen hours per day, believing that his five children could leverage a better place for themselves with a college education. Everything for us, nothing for himself, and this degree of renunciation announces itself in one word and one word only: love. Yes, I grew up in a blue-collar household. As did all my friends. I can remember only one kid whose parents were college-educated, and they were the only parents in the neighborhood who were divorced. I know that blue-collar world intimately, first living it in a working class town in Western Massachusetts, where I was born and raised, and, for the past forty-two years, here in rural northern Michigan. “The idea that people who think and write for a living are out of touch with real America” seems to me so entirely presumptuous, and cultivated in the service of yet one more political sound bite.

In that prior interview, you talked about an “imaginary elsewhere” that many of the characters were longing for, that pulled them out of their everyday lives, if only in their minds. Do you see that desire operating in the lives of these new characters as well?

In that prior interview, you talked about an “imaginary elsewhere” that many of the characters were longing for, that pulled them out of their everyday lives, if only in their minds. Do you see that desire operating in the lives of these new characters as well?

An anagram of desire is reside, and often story is generated by a character’s inability to embrace restraint, to stay put, to steadfastly refuse that impulse to pursue what may well be harmful. But as Stephen Dunn says in a poem called “Talk to God,” “Ask him [God] if when he gave us desire he had understood its power.” It’s a dynamic force, and makes for story, even if the action occurs only in the character’s mind as he or she leaps outward into some “imaginary elsewhere.”

Plus there’s an implicit tension created by what a place provides, and what it can’t possibly deliver. And this intensifies if you happen to live in a landscape, as Jim Harrison says, “ignored by the rest of the world.” And where, as the joke goes, there are only three seasons in northern Michigan: July, August, and winter.

So yes, desire—which forms both character and behavior—is inherent in these new stories. I really can’t imagine writing a story in which someone didn’t desire, as T.C. Boyle says, “to apply the pin to the swollen balloon.”

An article recently published in The Daily Beast advised writers who want to finish a book to (in the words of the title) “Write Every Day or Quit Now.” Though a lot of people found it unnecessarily prescriptive, I found myself wondering what you’d think, given what you described in our previous interview as your “hard core work ethic.”

What does your writing day look like right now? What advice do you give your students about developing a good work ethic for themselves?

Whatever the advice, writing well requires a fanatical persistence, and pursuit, if we mean to serve this passion honestly. As Thoreau said, “Writing isn’t a profession, it’s a condition,” and I couldn’t agree more. And what I tell my students is that talent must discover its equivalent in a hard core work ethic, because anything less will fail them miserably, and only in about a thousand different ways.

Last January Kwame Dawes, my colleague at Pacific University, gave a craft talk in which he used the phrase “at the confluence of ambition and humility,” which I loved. Yes, above all, stay ambitious for the work, and humble in its presence, and just keep whacking away at the keyboard. I also tell them to take themselves seriously, and to believe. That’s how the work gets done. No shortcuts, no strategies to make the process easier than it ever can or will be. That’s for wannabes.

As for what my writing day looks like? I’m an inveterate insomniac. I have not awaked to daylight in over twenty-five years, and so usually I’m in my office by 3:30 a.m., coffee in hand. I love the ritual, and the hours to work undisturbed until midmorning, and by which time it feels as if I’ve already put in a full day. I’m an inordinately slow writer, but over time, even at my pace, the stories eventually take shape, and that’s all that matters.

The epigraph to this collection is from Galway Kinnell’s “The Road Between Here and There,” a poem I’ve heard you quote many times. What do these lines mean to you now, and how do you see them reflected in these stories?

In his classic short story, “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” William H. Gass says, “Time is the only narrative.” If this were not true, the “prosers” would have nothing to write about. It’s how I define plot—by what changes in the story, because something must. As Margaret Gibson says, “Something that was here, expected / to continue being here, / isn’t.”

Sometimes, just to remind myself of this, I’ll walk outside at night and stare up into the eons. Our stay is brief, and “It goes fast, they say, / and it was going as they / said it.” (Derek Sheffield.)

I think of myself as a stargazer and this includes those day-blind stars. A dreamer, as my teachers used to refer to me, and one of the recurring motifs in both The World of a Few Minutes Ago, and The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot, are the constellations, and the nature of time and change, and how the future, which I think of as white space, becomes the present, which becomes the past, and then the distant past. And how time is stereoscopic, composite, or simultaneous, how the past lives inside the present, and, as such, enlarges it, providing us a history and a blueprint of who we are, and how we’ve arrived in this particular place, at this time. Is it any wonder that the element of flashback is so crucial in my stories?

Many of these stories feature children trying to interpret and find their way into the world of adults. Did you consciously develop that as a theme? If not, what might have led you toward that subject matter?

I don’t believe I’ve ever consciously developed anything as a theme. In fact, after the publication of Wanting Only To Be Heard, I learned from reading reviews of the collection that the focus of those stories, its unifying element, was the relationship between fathers and sons. With that in mind I went back and reread the stories, and sure enough, there it was.

Maybe a writer’s career is consumed by a single obsession, or two, or three. I’ve already mentioned my fascination with time and change, and yes, with kids who dare to hope, even against seemingly impossible odds. Their collective mindset is not that “this is as good as it’s likely to get,” and they mean to prove it, even if they have no idea how. Exactly at that age when a kind of human determination first takes hold as they begin to consider and concentrate differently on the world, and their place in it. A tumultuous time, for sure, and whether it has any bearing on anything, it is when I first picked up a pen and began to write. Who knows, maybe that’s why a part of me still lives a protracted adolescence.

My students often complain that all the stories we read in class are depressing. I tell them that that says less about my taste than it does about modern literature, but one thing I do really admire about your work is that you’re not afraid of happy endings. There were at least four stories in this collection where I was expecting something tragic to happen and instead things turned out reasonably well.

My students often complain that all the stories we read in class are depressing. I tell them that that says less about my taste than it does about modern literature, but one thing I do really admire about your work is that you’re not afraid of happy endings. There were at least four stories in this collection where I was expecting something tragic to happen and instead things turned out reasonably well.

Do you think some writers over-rely on conflict to raise the stakes in their work? How do you avoid that trap?

Maybe hopeful more so than happy, or at least more so than happy ever after, which, of course, is total fallacy. As Tony Hoagland says, “…even when the world seems perfectly arranged, I feel / a force about to take it back.”

My story “Wanting Only To Be Heard” does end tragically, and, even then, back in 1985, I tried everything I could not to write that ending, though of course at some point the story dictates, and the characters do what they do, and your only option is to write down what the story is telling you, and the outcome inevitable.

But more than thirty years later, I think you’re right. And your observation, by the way, was underscored in a recent Booklist review of the new collection. It’s no doubt one way in which my stories have changed. I felt it deeply after I’d written the ending of “The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot,” though that wasn’t its original ending. The earlier one seemed right at the time, so much so that I submitted the story in that version, only to retract it a few days later, knowing that this Charles Atlas thing I insist on—where those final couple of sentences have to hold up the entire world of the story—wasn’t there yet. I think in that final flash, when the two kids make eye contact with their father who is collecting snagged lures from a submerged log ten feet below them, allowed me not only to love them more, but to stop time and hold that moment for an extra click or two, before letting the story go on.

And I think it’s fair to say that at this stage, drama for me has less to do with plot than it does with language and character, and the “action” that takes place in the mind and the heart. This, clearly, was not the case earlier in my writing life.

“The Alchemist’s Apprentice” is dedicated to Vince Gilligan, the creator and producer of Breaking Bad, who went to Interlochen as a teenager. Was he one of your students? Has he told you what he thinks of the story?

Yes, Vince was a student of mine when he was a freshman at Interlochen Center for the arts, but he was not a writing major. His focus at the time was visual arts, and when he returned to the area a few years back, after decades away, and after all the critical acclaim for Breaking Bad, he asked if I’d show him around the campus, and which, during his absence, had been so totally transformed. When we stopped in the new visual arts building, he recognized a certain acetylene torch, and recalled how his metalsmith teacher had somehow procured a bunch of pure silver tracheotomy tubes, and how they melted them down, and that he, Vince, had made a pair of earrings for his mother.

I loved the story, but more so I could not get the image of those tracheotomy tubes out of my mind, and not long after, I wrote a story that begins this way: “My mom says she hasn’t the foggiest and that wherever Jimmy Creedy, her stay-over boyfriend, heisted all those tracheotomy tubes is anybody’s guess. ‘Possibly Dr. Frankenstein’s la-bor-a-tory,’ I joked, but she just shrugged, like yeah, maybe.”

I dedicated the story to Vince and sent him a copy, and he responded with such a kind and generous two-page letter. Here’s the first paragraph:

I absolutely loved “The Alchemist’s Apprentice.” To paint such vivid pictures of places and people in a reader’s mind and yet to do it so economically, in the fewest words possible…that is writing. Man, that is what it’s all about. Wonderful work.

I think you’re a genius with titles. One could almost read the title page of this collection like a poem. Where do they come from? Do you know them before you write the story, or do they come after?

I’ve never begun with a title, nor have I ever titled a story before it was finished. Oftentimes they’re embedded within, a phrase somewhere that seems compatible with the theme. But not always. The title of my previous story collection, The World of a Few Minutes Ago, is taken from a poem by Gregory Djanikian called “Violence,” in which the speaker says, “There is nothing so improbable as the world of a few minutes ago.”

How Like an Angel is taken from a Thomas Traherne poem called “Wonder,” which begins, “How like an angel came I down.” The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot, of course, are two of the constellations mentioned in the title story. In another, “Calcheck and Priest” are the names of the two main characters. “Wanting Only to be Heard,” the title story of my first collection, are the final four words of that story. And on and on.

Do you think you’ll write another novel? What are you working on now?

The likelihood of that lies somewhere around zero. I love the short story form, its economy and intensity. Frank O’Connor said, “…there is in the short story at its most characteristic something we do not find in the novel—an intense awareness of human loneliness.” I see that as an affirmation, and have no trouble whatsoever translating it to beauty. I am, after all, Irish, and which no doubt explains why I have seventeen covers of “Danny Boy” on a single CD.

I just finished my first story since The Goat Fish and the Lover’s Knot a few weeks ago, and I’ve been thinking lately that the timing might be right for a New & Selected. We’ll see. I’ll let you know whenever it becomes clear to me!