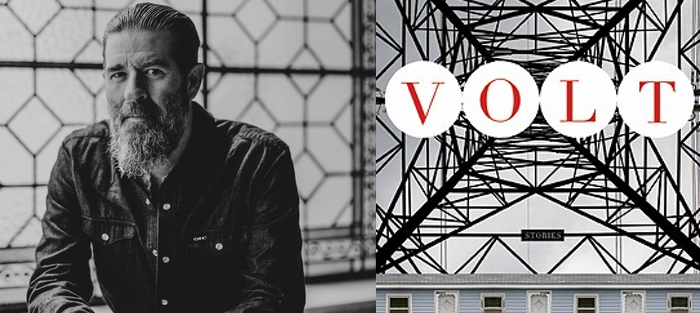

Alan Heathcock is a nice person. At the Esalen Writers Camp in Big Sur, California, where we met in the summer of 2015, he was unfailingly kind and generous with the students, accessible and friendly. One night, he held an entire room in thrall with a twenty-minute story about a high school friend who had died too young, the entire monologue delivered Moth-style, without written notes. I looked forward to reading his work when I got home, and I thought I knew more or less what to expect.

But the stories in his debut collection, VOLT (Graywolf press), were not nice stories. They were taut, lyrical, electric, full of violence and suffering and unfairness. In one, a boy helps his father hide a body; in another, a sheriff exacts her own personal revenge on a sinister local hermit. If redemption comes at all, it’s hard-won, paid for in grief and confusion. These are not nice stories, but, like their author, they have something to tell us about living and losing.

VOLT was a “Best Book” selection from numerous newspapers and magazines, including GQ, Publishers Weekly, Salon, the Chicago Tribune, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The collection was named a New York Times Editors’ Choice, selected as a Barnes and Noble Best Book of the Month, and was a finalist for the Barnes and Noble Discover Prize. Heathcock has won a Whiting Award, the GLCA New Writers Award, a National Magazine Award, and has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Lannan Foundation, and the Idaho Commission on the Arts. A film version of his story “The Staying Freight” is set to begin production in 2017. A native of Chicago, he lives and works in Boise, Idaho.

Interview:

Mary Stewart Atwell: What is your connection to the rural Midwest? Did you grow up there? If you wrote these stories elsewhere, how did you capture the feel of that Midwestern landscape?

Alan Heathcock: I’m very coy in not saying where Krafton is set, but it’s definitely rural America. That said, you’re absolutely correct in that I have a deep connection to the Midwest, and those landscapes are integrated into the stories. As for the Midwest, my father was raised in a very small town in southern Illinois. My mother was raised just over the Indiana border, also in a small town. I was raised in a town just south of Chicago, and for anyone who’s traveled around Chicago knows, things turn from city to farmland very quickly.

More to the point of your question, I’m absolutely drawn to Midwestern landscapes. I do see great beauty in the corn and bean fields, in the barns and grain silos, in the stretches of deciduous woods, but I also see mystery and isolation. To say that differently, when I look out over corn fields, I sense a story. There’s something alive in those rows. And when I see the farm-house down a long lane between fields of corn, I wonder about the people inside. Life in rural America is a profoundly different kind of life than the city or suburbs, and even with the onset of technology exists in its own time and culture. From my own experiences, and those of my family and friends, I’ve heard stories or directly witnessed tremendous drama in these landscapes. Ghosts of headless coal-miners roaming the hills, drug deals gone wrong, people run-down by trains or drowned in a quarry pond. Everyone knows someone who’s died in a farming or hunting accident. All of this drama happens in the pressure-cooker of a small town where you have to face your actions and the actions of others. Add to the mix an earnest religious component, folks who look out for each other, who believe in honesty and hard work, and you have a place the neatly holds the myth of America. The truth of this mythology is true not just in rural Midwest, but all over America. In fact, it’s been fascinating traveling all over the country with the book and having folks from Alaska or Maine or Alabama or Idaho have as strong a sense of recognition with my stories as folks from Illinois.

More to the point of your question, I’m absolutely drawn to Midwestern landscapes. I do see great beauty in the corn and bean fields, in the barns and grain silos, in the stretches of deciduous woods, but I also see mystery and isolation. To say that differently, when I look out over corn fields, I sense a story. There’s something alive in those rows. And when I see the farm-house down a long lane between fields of corn, I wonder about the people inside. Life in rural America is a profoundly different kind of life than the city or suburbs, and even with the onset of technology exists in its own time and culture. From my own experiences, and those of my family and friends, I’ve heard stories or directly witnessed tremendous drama in these landscapes. Ghosts of headless coal-miners roaming the hills, drug deals gone wrong, people run-down by trains or drowned in a quarry pond. Everyone knows someone who’s died in a farming or hunting accident. All of this drama happens in the pressure-cooker of a small town where you have to face your actions and the actions of others. Add to the mix an earnest religious component, folks who look out for each other, who believe in honesty and hard work, and you have a place the neatly holds the myth of America. The truth of this mythology is true not just in rural Midwest, but all over America. In fact, it’s been fascinating traveling all over the country with the book and having folks from Alaska or Maine or Alabama or Idaho have as strong a sense of recognition with my stories as folks from Illinois.

Even though I now live in Idaho and have adopted some affinity for sage flats and mountains, the corn fields are still my muse. On any given day, I’ll sit in my writing trailer, close my eyes, and I can see the corn wavering, the silk tassels glittering in the sunlight, the breeze rattling the leaves, and if I’m quiet and patient a story will emerge.

You mentioned that accidents can be frequent on farms and in rural communities, and your debut collection, VOLT, begins with a particularly tragic accident. In “The Staying Freight,” a farmer named Winslow Nettles stops his tractor to find that he’s run over his young son. Did you know from the beginning that the story would begin with this scene, or was that a decision made in revision? Did you always know that this would be the first story in the book?

That was a decision made by my brilliant editor, Fiona McCrae, at Graywolf Press. I was surprised and little worried at first because that meant on page 1 of the entire book the reader would cross the death of a child. Not that I really have any “soft” stories that might ease a reader into the book, but that story especially packs a punch. But Fiona was right. That story sets the temperament for the entire collection in that it’s about grief, but also about forgiveness.

A lot has been made of the darkness in my book, but I’m proud that each of the characters in my stories is searching for some moral good (whatever that might be). They don’t always find it, but they’re looking for forgiveness or truth, looking to be saved from horrors that surround and occasionally possess them. The darkness is easy to write. Just as tragedy is easy to capture. What’s truly difficult, what takes a great deal of meditation and deep thought, is understanding how to move characters through tragedy and into some edge of redemption that feels authentic and earned.

I’m also very pleased that I’ve adapted “The Staying Freight” into a screenplay that’s now very close to being “greenlit” for a major motion picture. The story is based off of family tragedies, things that really happened, and I feel the story can hold a powerful and important place in the world, taking a reader, and now potentially a viewer, though the downward spiral of guilt and shame after tragedy and into the beginning edges of true forgiveness. The world we live in now is getting more and more coarse, and I’m proud to offer an example of forgiveness, and hopeful the story can help someone out there who’s suffering.

I’m interested in what you said about the possibility that the story holds to offer comfort or hope to a reader who has suffered loss. I’ve always found the idea of fiction as a form of emotional education really powerful—you can find it in some of George Eliot’s essays, and in John Gardner’s “On Moral Fiction.” However, I think this way of thinking can sometimes seem unfashionable or even backward to readers who are interested in the intellectual and conceptual dimensions of fiction. How do you balance your interest in the formal aspects of your work and its potential to inspire feeling or sympathy in readers?

Great question. Let me see if I can unpack it a bit.

I was in graduate school for a long time. Eight years. I have two MFAs, three years in a Phd (I didn’t finish). For so many years I was engaged in conversations of what’s right or wrong in literature, as if there was such a thing. Genre versus literary. MFA versus NYC. Experimental versus realist. My intellectual life revolved around these types of questions, and, I suppose, to an extent, I’ve arrived at where I am by passing through the answers.

But now I’m at a place in my life/career that I have no interest in those conversations. I think we each write for ourselves and find value in the writing for different reasons and our brains are wired in different ways and we’ve come from different places with different life experiences and we create in different ways and there is no forward or backward, only how the work feels powerful inside us, and how we define our purpose in a way that feels true to who we are and/or who we want to be.

The endeavor of my days is to try and become the best possible version of myself, which is to say I must understand who I am, what I want to accomplish, then be absolutely clear-eyed in how to achieve my goals. I’ve been mentoring a very talented young writer and told her the other day that there are three basic things we must do to “succeed” as artists. 1. We must get our education (this doesn’t need to mean formal schooling) in order to precisely determine our own personal definition of quality. 2. We must be clear-eyed in looking at our own work in order to determine if we’re meeting the standards of our own personal definition of quality. 3. We must be willing to work as long and as hard as needed, revise as many times as it takes, to get our work up to the standards of our own personal definition of quality.

So the very first step is always to understand how we personally define quality (which I understand is easier said than done).

To bring this all back around to your question about the role my fiction might play in the lives of others, I’ve determined that my personal definition of quality includes writing about things that scare and confound me and searching out the truths of the human experience that might lend the light of insight or maybe even a bit of order to the darkness. I write first for myself, but understand because one of the highest purposes of art is to allow us to see ourselves though in a way that’s bearable, that others (a reader) might benefit, too. There’s a much longer answer to why this is a part of my definition of quality (my hard-wiring, my life experiences, where I’m from, what books/films/plays I love), but I write, in part, because I’m suffering, and the world is suffering, and I believe a good story, well told, can help as much as anything. For me, the balance is clear—all of my education, every scrap of craft, every precise thought on quality, I now funnel into my desire to expose and lessen suffering through story.

I’m not looking for approval or even understanding. I don’t care about fashion. I’m not suggesting my views onto anyone else. I sit by myself day after day, trying to make sense of the world through words and characters and stories. I work the way I work, believe the things I believe, because they resonate powerfully inside me and fill me with a sense that my life and work have purpose.

These are really admirable goals for a writer, and I can see how they may have influenced the content and tone of your collection. Before we totally move on from craft, though, I wonder if we could talk a bit about voice. The sentences in VOLT feel taut, a bit stylized, and (I think) different from the voice of your nonfiction. Were there particular writers who influenced the tenor of the sentences in these stories? How did you keep it consistent?

I’ve developed my “voice” over time. When I was first starting out I was terribly afraid of imitating other writers. Back then, I’d only read a handful of books so the influence of every book seemed really obvious and I just knew people would see that influence and call me a fraud. At some point, though, I came to understand that the learning process, especially when it comes to writing prose, always begins with imitation before being digested into something that might later be called one’s “voice”.

I started always carrying a highlighter with me while reading. With every book I read, I’d highlight anything I thought was worthy—a great sentence, great image, great bit of dialogue, a great verb, whatever. Then I’d start each writing day by copying everything I highlighted the day before into a notebook. I’ve done this now for nearly twenty years. I have dozens of notebooks filled with words and sentences and paragraphs, my own reference library of quality.

With the longview I have now, I see that what I was doing from the start, what I’ve been doing for a couple of decades, is curating my aesthetic. My “voice” is a curated accumulation of everything I’ve highlighted from everything I’ve ever read. I keep it consistent because it’s completely my taste, curated over reading hundreds of books, and by writing every day into my notebooks. If I say that certain authors are “influences” on me what I really mean is that there are certain authors that I seem to have kindred sensibilities in how and/or what we’ve written. It’s not that I want to be like them, like I’m dressing in some costume to play some role. It’s that I am like them.

When I read Cormac McCarthy or Flannery O’Connor I recognize myself wholly in their work, in both how they write but also in what they write. Those two are clearly my strongest influences. In his prose, James Salter offers me a powerful kinship. As does Michael Ondaatje and Daniel Woodrell and Joy Williams and Toni Morrison and Marilynne Robinson, even sci-fi writers like J.G. Ballard or Jeff Vandermeer. I read every day and I read all kinds of books, scouring them for every scrap of quality I can capture and curate for my own use.

I’ve gotten the impression that film is also a big influence on your fiction, and I know that several of the stories from VOLT are being produced as short films. Before we talk about those projects, can you say a bit about what film has meant to you as a writer?

I was at a dinner party recently and we were going around the table and each answering the question: if you could have one and only one singular experience for the rest of your life, what would it be? My answer was going to the movie theater. Don’t get me wrong, I find pleasure in a lot of other things, but I’ve always loved going to the movies: walking up that ramped hallway, stepping into the theater, the size of the screen and the sound, the immersive and transporting quality of it all.

My parents were huge movie buffs and they took me to whatever they were seeing. They just took me along because it was cheaper than a babysitter, but didn’t realize I was actually paying attention. I saw so many great films growing up, and some I remember the most are: All the President’s Men, Tender Mercies, Coal Miner’s Daughter, Norma Rae, Mad Max, Apocalypse Now, on and on. I saw dozens of films and those films I saw at such an early age had a huge effect on me. These days, between watching movies at home or going to the theater, I average seeing well over 200 movies a year.

Beyond being a fan, I’m also a student of film. As a writer, I’ve outlined the plots of many of my favorite films, and, as an exercise, have written out many of my favorite movie scenes as if they were fiction. Since film is all external, writing the scenes as fiction has forced me to exercise my ability to write into the empathetic interior of the characters. It’s highly instructive and challenging and liberating. I’m a visual person and a visual writer, so cataloging images is a big part of my movie-watching habits. In the same way I’m “curating” everything I read, I’m doing the same with everything I watch.

In general, I find I’m at my best as a writer if I’m consuming a huge amount of words and stories each day. The great gift of my genetics or upbringing—or whatever has made me into what I am today—is that if I have an addictive personality I don’t turn to drugs or alcohol or anything harmful. I’m completely addicted to story, and having books and films in my life feels enriching and beautiful. That these activities I adore—reading and watching film—help me become a better writer (and person, I’d argue), and that I’m making a living from my passion for story, is a blessing I never take for granted.

In general, I find I’m at my best as a writer if I’m consuming a huge amount of words and stories each day. The great gift of my genetics or upbringing—or whatever has made me into what I am today—is that if I have an addictive personality I don’t turn to drugs or alcohol or anything harmful. I’m completely addicted to story, and having books and films in my life feels enriching and beautiful. That these activities I adore—reading and watching film—help me become a better writer (and person, I’d argue), and that I’m making a living from my passion for story, is a blessing I never take for granted.

After hearing about your love of film, I’m curious to know about how the short film of your story “Smoke” (now available on Vimeo) came about. How did the filmmakers approach you? How much input did you have in the writing of the script, pre-production, casting, etc.? I imagine you had a strong vision of what the final version of the film should look like—did it meet your expectations?

Smoke was a huge learning opportunity for me. I’ve loved movies for so long and wanted to get more involved in the world of film so I jumped at the chance. The filmmakers (Cody Gittings and Stephen Heleker) were former students of mine, both brilliant writers and guys I liked and trusted. The process was a cool partnership. I came on as a producer to have my voice in the room, but really just as a means to learn.

The process of taking a film from inception to completion was highly instructive and totally invigorating. To me, the biggest challenge in filmmaking was to tell a story in precision with so many people involved in the process. When I write, the challenge is that there’s only me—I’m the director, actors, set designers, everything. The advantage of writing prose is that I can move any and all parts of the story into absolute precision. Making the film was interesting in that the creative leaders (Cody and Stephen) really had to be highly organized and great communicators to get all 35-40 members of the crew doing what they needed to do to enable a story to be told in precision. I had a voice in the process all the way through, but tried to hang back and just learn.

The end product is a film that’s not perfect, but is really damn good and brilliant in spots and one that I’m proud to have associated with my story. That’s saying a lot. The actors were amazing. Joel Nagle has been in many films and was perfection as the father in the film. Amadeus Serafini played the son. This was Amadeus’ very first role on screen and he slayed it. Now he’s a big star on MTV’s show ‘Scream’ and I predict he’ll have a long and amazing career.

All in all, I’m really really pleased with the film, but the real thrill was that my involvement was like getting another MFA—I just learned so much.

I think the big lesson here, the thing I tell my students, is that at age 43 I decided to humble myself enough to learn something new. That means I had to admit there were things I didn’t know. I was very clear-eyed about what I didn’t know and just jumped into being a highly motivated learner. I asked questions, I read books, I watched and listened and though I made lots of mistakes it was invigorating. Sometimes we make learning seem like a chore, or fear/doubt/shame disables us to just admit what we don’t know and that shuts down the possibility of learning. I tell my students to never get upset over what they don’t yet know. Learning can and should be thrilling as you feel yourself moving toward who/where/what you want to be.

Along with your work in film, I know that you’re also working on a novel. At the conference where we met, you mentioned that it was partially inspired by your desire to provide your young daughter with a good fictional role model. Can you talk about the story, and specifically your intentions in creating that main character? Also, how is the novel coming together? Do you have a deadline in mind?

A few years ago my teenage daughter found a list on the Internet on “the strongest female characters in movies”. The list was pathetic. She was frustrated to find that there just weren’t very many solid fictional female heroes. I tried to come up with more examples, thinking maybe the list she’d seen had some omissions, only to discover that there really wasn’t a lot out there. I’d already been working on the novel and had a female protagonist, but as an answer to that list was then motivated to write a female hero who wasn’t: 1. The sidekick to a man. 2. Motivated to win the love of a man. 3. That her power wasn’t based on her sexuality. My personal favorite example of a powerful female protagonist is the character Ridley from the movie Alien, and to a degree my character is cut from the same jib. The challenge is to write a character who’s strong and capable and persistent while allowing them to be flawed, because the flaws are what make them interesting. So far I’m pleased with this main character, and I’m hopeful my daughter will be pleased, too.

The other challenge of the book is that it’s about a near-future and a civil war that breaks out in America. I’ve been working on the book for nearly eight years now, and the politics of our time have been sneaking closer and closer to this fictional reality. It’s terrifying, and the challenge is to use what I see in the world while at the same time allowing the narrative to exist in its own space. I’ve always used my fiction as a means to explore things that scare and confound me, and this novel is saving me right now. It’s helping put order into the disorderly, helping me extract insight out of fear.

To answer your specific question, the novel is coming along nicely. I’m very deep in the process, but have a little ways to go. If there’s one trait I’m aware helps me it’s my patience. It’s up to me to allow the time and effort to get this book done well. I’m committed to the book for as long as it takes, though I can sense the end coming nearer.

Beyond that, what I know is that the world is made of stories. Every day, our collective reality is shaped by narratives. This is not limited to writers. This is a truth to the human experience. Business decisions, political decisions, personal decisions, are affected by stories. The stories we read in the news, what we choose to believe, what we discard, where our personal experiences meet and bump against the experiences of others, the stories we tell each other to get things and to compel and punish and shame. We embrace and condemn certain stories to fit into certain communities. Our stories are our armor and our swords. Our expressions of tenderness and love. I find this to be empowering, liberating, in that if I do my job well then I can affect the world with my words. I can create a hero to inspire my daughter. I can hold a mirror to the mess of our world, maybe make people take pause. I can provoke conversations. I can reveal insights. I can make people think and feel and imagine in ways they otherwise wouldn’t. Because of this, I know that the act of writing a story is an act of hope. Even on the hardest of days it’s that hope, more than anything else, that keeps me going.