Lenore Myka and I met in Boston, where we both lived until Lenore moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, this fall. We are both graduates of the Warren Wilson Program for Writers, and we’ve both published first books recently.

Myka’s debut story collection, King of the Gypsies, won the G. S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction and was published by BkMk Press in September. Post-communist Romania is a common thread in the eleven stories in this collection, but the characters that inhabit these stories—orphans and American service workers, immigrants and child prostitutes—transcend place and politics.

Interview:

Lynette D’Amico: Eudora Welty referred to setting/location as, “the ground conductor of all the currents of emotion and belief.” The more specific the place, the more resonant and meaningful the action. How does location/setting function in King of the Gypsies?

A long time ago, I heard an elderly writer lament the lack of setting in the stories his students were producing in some MFA program somewhere. I do feel there is an absence of setting in the stories of my students. My younger students say that “description is boring,” as if description were synonymous with place. And yet, when you read people like Carver or Beattie, writers who were called, for better or worse, minimalists, I feel a deeply rooted sense of place in their stories. It’s because their characters embody those places in some mysterious way. It’s ye olde iceberg, right? Even if the place doesn’t go into the story, it’s there in the writer’s mind and through some strange process of osmosis reveals itself on the page somehow.

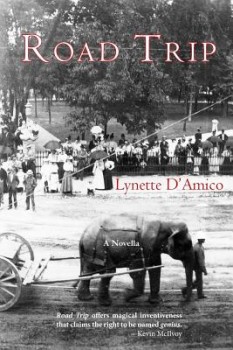

In terms of craft, I don’t feel you can have character without setting, whatever that setting might be, whether it’s a room in a house or Tulsa, Oklahoma. And when we create character we’re creating identity, though that identity might change over the course of the narrative. When I read your book Road Trip (Twelve Winters Press), I thought you did this really well. Within the first few pages I felt that despite the fact that Pinkie and Myra were traveling, they were clearly products of the places they’d come from, clearly products of the Midwest, of Illinois and Minnesota and the Wisconsin they were driving across. As humans, we are molded and informed by our environment; we don’t live in vacuums. We may not like our locations—we might bump against them or reject them—but for better or worse, they become a part of us. I don’t live in Buffalo, New York, I haven’t lived there since I was eighteen, but that place is stuck inside me somewhere. Just like Romania and Boston and Washington, DC—all the places I’ve ever lived, are. Just as I’m sure Florida will stick inside me over time.

Where and how does the world enter your work? The writer Deborah Eisenberg has said in a Paris Review interview, “I’ve always been ready to oppose. I would say that I was born with the basic sense of politics I have now.” In your writing do you reinforce your politics or discover them?

This is tough. For one thing, my writing process is sloppy and very, for lack of a better word, organic. I don’t know much about what’s going to come next, not even the next paragraph. If you had told me to write a book about Romania, the image in my head at its start would have been very different from the one that has resulted in King. (I also didn’t set out to write a book about Romania.) So it’s hard to know really, if writing reinforces or helps me discover my politics.

This is tough. For one thing, my writing process is sloppy and very, for lack of a better word, organic. I don’t know much about what’s going to come next, not even the next paragraph. If you had told me to write a book about Romania, the image in my head at its start would have been very different from the one that has resulted in King. (I also didn’t set out to write a book about Romania.) So it’s hard to know really, if writing reinforces or helps me discover my politics.

I guess what I can say is that I’ve always bristled against this notion that literature shouldn’t be political. I heard that a lot in graduate school and never really understood what people meant by that. I guess that books shouldn’t have agendas. But don’t all books have agendas, whether the writer knows it or not? Another word that confuses me always is intent, as in the writer’s intent; I think maybe this is similar to agenda. Maybe the point should have been reframed: You can write political fiction but the reader shouldn’t feel you are beating them over the head with an iron skillet.

Here’s the thing: I’m a deeply political person. I have strong opinions, a strong sense of fairness, and my way of working all this out might actually appear in my writing. I don’t think I could arrest myself from this impulse; I don’t think I’m aware of it enough, in the process of crafting stories to do so. At the same time, I am always changing as a human being—my opinions evolve, become more nuanced, sometimes stray entirely from an earlier belief system. As a result, my writing is always changing. Sure, there are fundamentals that remain—the foundation of most of my work. But the rest is forever fluid.

You said to me once that “The only thing that feels empowering to me is writing.” Empowering as a global citizen? As a woman writer? Do you see writing as a vehicle to effect social change?

Did I really say that? I must have been having a singularly optimistic day! I think this probably came from a sense of hopelessness I feel as a citizen in this country these days. Voting feels ineffective, protesting, calling my representatives. What’s left after that? Writing.

Not too long ago I heard another writer say that her intent as a writer was to “change the world.” I have to say, I was shocked when I heard her say that; I may have even guffawed. Change the world? That’s preposterous! And, I don’t know, arrogant; it struck me as arrogant and narcissistic. But I think it’s because I’ve never felt that my writing could do this. My modest Catholic upbringing. Don’t draw attention to yourself; don’t brag. I have the opposite problem of that other author; I tend to undersell my work (a terrible female problem).

And yet, I think that writing can have a significant impact on culture. It can provoke and incite. It is also a mirror on the world in which is exists. And when I think about some of the authors PEN America has been highlighting—writers who are persecuted, arrested, sometimes killed—I think that maybe writing really can change the world. If governments feel that threated by the written word that they need to arrest or even execute the author to try and squelch free speech? Those authors must be doing something right.

And on a smaller scale, I think about my students and how liberating it is for them, to write. They are being transformed on an individual level. It’s not a revolution, but maybe these smaller, incremental changes have a larger impact on the world.

In “Manna from Heaven,” the American service worker, Stella, who works in an orphanage, says after she gets sick at a Romanian pig roast that includes the slaughter of a pig that “she preferred her meat in abstractions—drained of its blood, deboned, de-hoofed, chopped and quartered, frozen, preferably ground—before she came in contact with it. She understood this: she had lived a sheltered life, something her friend would never understand since no one here had ever lived that way.” Has the critical response to your book included any preferences for the “darker” subjects—for example, child prostitution—to be presented in abstractions?

Oh, yes! For one thing, there’s the Romanian response. One man I’ve gotten to know said that the book was unlikely to be well-received among Romanians because they were tired of the bad press their country had been getting for years, and the stories about the orphanages and the street kids, the problematic adoptions, were just reinforcing those stereotypes. I get that defensiveness; I do. At the same time, it has been my hope that this book would transcend the specificity of place, at least just a smidge. Romania’s problems are, after all, the world’s problems.

On the American side I am much more impatient. A story: The mother of my oldest friend threw a house party for me a couple of weeks ago. All of the people who attended hadn’t yet read the book and it was my job, I guess, to persuade them to do so. One of the women said her son had encouraged her to read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me and she was finding it very difficult to stomach. She wondered: Would my book be any different, perhaps provide entertainment or a happy Hollywood ending? Her words. She said: I’m an American; I like happy endings.

I find this a difficult attitude to counter. For one, I’m an American and rarely do I like happy endings, at least not in fiction. Two, literary fiction is art. I’m creating, however unsuccessfully, art, and art is something that should provoke, should make people think, respond, react. Do you go to a Picasso exhibit to make yourself feel better? Do people listen to Mahler to improve their mood? I responded to her in the same way I did at a reading a few nights earlier. I essentially said: I’m not here to make you feel good. That’s not why I write.

I share an aversion to agitprop, and yet I believe in the transformative capacity of art. When I hear, mostly from family members, something along the lines of “I don’t want to read (or see) anything depressing”—which usually just means a realistic depiction of life with realistic people engaging with realistic issues—I have to resist the urge to puke. We live in the world! I think there is a dangerous tendency in America for people to sit at home and watch sports or Disney princess movies. Anne Bogart, a theatre director, says, “Our job as artists is to give voice to dead people. There are people who didn’t finish their sentences, people who didn’t have a chance. Our job is to listen to what’s before us, so that the page is not blank. The page is these screeching voices that didn’t get the chance to finish what they were saying. And it’s our job to fill up with them, study them, and then give them voice.” Sometimes I think my writing is all about giving voice to dead people. Such a chipper thought…

I share an aversion to agitprop, and yet I believe in the transformative capacity of art. When I hear, mostly from family members, something along the lines of “I don’t want to read (or see) anything depressing”—which usually just means a realistic depiction of life with realistic people engaging with realistic issues—I have to resist the urge to puke. We live in the world! I think there is a dangerous tendency in America for people to sit at home and watch sports or Disney princess movies. Anne Bogart, a theatre director, says, “Our job as artists is to give voice to dead people. There are people who didn’t finish their sentences, people who didn’t have a chance. Our job is to listen to what’s before us, so that the page is not blank. The page is these screeching voices that didn’t get the chance to finish what they were saying. And it’s our job to fill up with them, study them, and then give them voice.” Sometimes I think my writing is all about giving voice to dead people. Such a chipper thought…

I like this idea of giving voice to dead people, or maybe people who never existed. Or simply people who are voiceless in society (street kids, for example). I write to make sense of the world, to make sense oftentimes of what appears to be the senseless. I write because I have an insatiable curiosity about people who are unlike me. This collection and my love of travel dovetailed quite nicely because I think they’re sprung from the same impulse—to know what it is like to be someone else, to live a life wholly unlike your own. It requires empathy, something I seek to practice and something I try to inspire in my creative writing students.

It’s been my experience at readings for Road Trip that readers always ask what my story is based on. I’m often asked who is Pinkie, the “white girl from Springfield, Illinois, with limited self-regulating abilities.” I started out saying that I had invented the characters, which so clearly disappointed readers and shut down the conversation. Now, I push a little to say that the model for the complicated relationship between Pinkie and Myra Stark is based on the relationship between Sula Peace and Nel Wright from Toni Morrison’s Sula, and the line in particular “Being good to somebody is just like being mean to something. Risky. You don’t get nothing for it.” That line is at the heart of the relationship between Pinkie and Myra. Have readers asked about where your characters come from, say, the character of the young girl Irina? And how do you respond?

I love that quote from Sula. Beautiful. And it really does encapsulate the relationship you create in Road Trip. I think that’s a wonderful way for readers and audiences to better understand your process. And I think that’s what those questions about the kernels of inspiration are all about: People want to understand the process of writing a book.

In my experience, people definitely want concrete information about where the stories come from, and like you, I’ve emphasized imagination and creativity; like you, people seem disappointed by this answer. It’s funny you should single out Irina because she is nearly always the character people have in mind when they ask this question. And maybe, unlike you, there is in my work a bit more of reality. Irina isn’t a kid I knew, but she is, in a sense, a collection of kids. In “Tutors” I was very much thinking of a friend, though her personality is much different from Dana. I guess the best way to put it is that these people are springboards for the story. But I don’t always start with a character; most things start with an image or a turn of phrase that strikes me somehow. I can’t say what the stories are actually “based on” because I don’t know where they’re going when I write them. In retrospect I can kind of guess what the inspiration was, where it came from, what it was supposed to be about, but I don’t know that in the process of writing the story.

Lynette D’Amico

I made a conscious choice to add non-real elements to Road Trip such as ghosts, and I loved the permission it gave me to play. If Americans have heard anything about Romania, it’s something about vampires and Transylvania. There’s a little bit of a hint of the supernatural in “Wood Houses” and “Song of Sleep,” a suggestion of something darker, hairy, a loss of control or giving over; sleep that is deathlike, music that acts like a drug, dead goats. Did you consider pushing these elements? What was the experience of writing past stereotypes of Romania?

The ghosts work for Road Trip because in a sense it is an unlikely book in which to have them (though likely when considering family history—family history as a sort of communal ghost story, that is). It provides an element of surprise for the reader and keeps us engaged. But ghosts in Romania—overt ghosts—it’s just too damn predictable. And vampires! Even worse!

“Wood Houses” was the only place I considered pushing to this realm of the supernatural, but in the end concluded it would’ve lost its impact if I’d been direct with it. My hope is that because there is this uncertainty about Stefan, this mysterious sinister quality to him that could be supernatural, the reader feels unsteady. If it were simply revealed—he’s supernatural, a real live monster—that seems to take away the mystery for me because it’s explaining what the reader already suspected were true.

Romania is already a place steeped in folklore and magic and violence. That stereotype is useful only insofar as it serves as mood lighting, a backdrop, at least for my writing. But one book I much admire and mention in the back of King—Bogdan Suceava’s Miruna—uses the supernatural in a way I never would have been able to conceive. Suceava keeps it fresh, and his Romania, as a result, is an entirely new place.

In some of our discussions we’ve talked about the high costs of creativity, what it costs to be an artist in the world today. How are you piecing together your life as a writer?

Once, when I lamented to a faculty advisor about the state of constant struggle I’m in to balance writing and the rest of life, he replied, in essence, get used to it.

I imagine I’ll always wrestle with this issue. But the long and short of it is that I try to find work that provides flexibility and time, and meets my financial needs. I’ve done this rather unsuccessfully for several years. I live frugally, probably more than the average American, though I don’t feel like I’m depriving myself all that much. I do wake up at night worrying about my quality of life when I’m seventy-five. At the same time, I cannot imagine giving up writing, so I guess that’s a risk I’m willing, at least for now, to take.

But to be less dramatic about it, I’m lucky. I have a working spouse who is a huge champion of my creative work. We decided together not to have children—which doesn’t make me lucky but does relieve me of the burdens parenthood can create financially, emotionally, and creatively. I have friends and family who have supported me financially and in other ways. My parents paid for my bachelor’s degree. I remember my older sister reminding me when I was possibly the poorest I’ve ever been that I was lucky, I had a safety net if ever I wished to call upon it. I don’t think you can underestimate the power of this.

It’s impossible for me not to view being an artist through the lens of economic disparity in our country. Like other facets of our culture, there is an industrial complex that has been created around writing. To paraphrase Heidi Klum: if you have the resources, you’re in; if you don’t, you’re out. I have benefitted from this industry because I have some resources—to get an MFA, to go to conferences and network with other writers and editors and artists, to be a member of professional organizations, to hire a publicist, to pay submission fees to journals and magazines and contests, to take time off from work to write. Obviously, these things don’t make you a better writer, but they help to build a career. Writing is no different than being in business; many people advance because they know people who know people. It’s the way of the world, as my dad would say.

But what about the people who don’t know people? What about the single mom poet who has to work two jobs and still can’t pay bills? The unfortunate outcome of this is that what constitutes American letters—at least in the literary world—is narrow and—dare I say it?—exclusive. It’s not representing all the many voices that contribute to our contemporary culture.

At the same time, I also think there’s something about this world that distracts us from the point, which is writing, right? You can spend an awful lot of time being a writer without actually writing anything. Don’t get me wrong—I’m just as impressionable as the next gal and do spend time on these professional pursuits. But I’ve found that the more I engage in them, the more I question my motives.

We’ve talked a bit about our reluctance to promote ourselves and our books on social media, to commodify our work, which is so essential to do with a first book—probably with any book unless you’re Elena Ferrante or Donna Tartt. How do we sell ourselves on selling?

I don’t know that I have an answer to this question as of yet, since I’m in the midst of the process with my first book. But I’m currently living by two philosophies. The first is my father’s: I’ll try anything once. The second: authenticity.

What about for you?

I have found that what redeems selling for me is to pitch to other writers. Every writer I have approached about doing a reading or an interview together has been more than willing and often relieved by the idea.

That’s a great point. I must admit I’m humbled by the generosity of people, especially other writers. We have the unsavory reputation of being competitive and petty, but it’s true I’d never have guessed that from the experiences I’ve had. From the start of writing this book to this promotion phase, people are incredibly generous.

What’s next? Any predictions how living in Florida will influence your writing?

Florida began influencing me as a writer long before my spouse and I moved there. We’ve been visiting my parents for several years, primarily to escape the dark, cold New England winters, and I’ve long been struck by how surreal, complex, and extreme a place it is. I recently listened to a 2012 interview with Ben Lerner in which he talked about grappling with the changing landscape of his native Kansas, which is in essence a struggle with the changing landscape of America, its uniform, generic, big box strip mall thing. This idea that wherever you go you can find the same restaurants, the same shops; there’s no need to navigate in a foreign place. I’m obviously less eloquent here than Lerner was, but he seemed to put the finger on precisely what fascinates me about Florida. It is a place of profound beauty, but as in lots of places in America, you have to search hard for it sometimes. I am a deeply aesthetic person so I’m being challenged living in an environment that seems designed for ease of function and convenience. It is a place where the natural world is being squashed and yet nature constantly asserts itself. We cannot keep the gingkoes out of our house; the ibises won’t get out of the road; plants and trees will grow wildly and swiftly if you allow them to; we live in fear of hurricanes and floods and alligators that might eat our beloved dog. It’s a dramatic shift from New England.

I think of Elaine Scarry and her belief that palm trees were ugly and then discovering at some point in her life they were the opposite for her. It’s these contradictions that inspire me. I wrote a short story set in a Florida retirement community that won the Cream City Review short story prize, and I have aspirations of expanding that into a longer work, to explore some of these ideas that capture me.

But in the interim: I tend to work on multiple things at once. For now, most of my focus is on a novel that is set in a place that looks much like the steel town in upstate New York where my parents grew up. While it’s a domestic book, the themes are not dissimilar to those found in King. We all have our drums to bang on and I most certainly have mine.