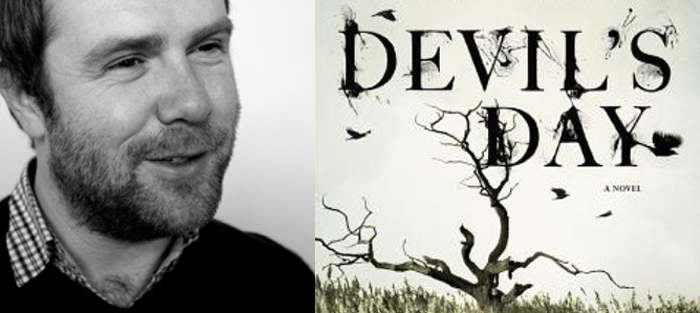

Andrew Michael Hurley’s debut novel, The Loney, was first published in the UK in 2014 in an edition of under three hundred copies. Yet proving the old adage that you can’t keep a good book down, it was soon republished by a larger British press and went on to with the Costa Award for first novel the following year. It was then brought out in the US in 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt—with a blurb from Stephen King, no less—and the publisher subsequently released his second novel, Devil’s Day, co-winner of the Encore Award from the Royal Society of Literature, here on this side of the pond last fall.

Both novels are gothically dark, geographically remote, deeply atmospheric, and slow-burning. They don’t leap out at you with a cinematically-styled crisis, but invite you to watch closely as characters become enmeshed in and transformed by worlds that are familiar to them, yet semi-alien. Reading Hurley’s books, I felt the damp weather of the northern English countryside in my bones. I also felt the peculiar suspense of knowing that his characters would turn out to be something other than they seemed to be, and although I knew which characters those would be, I didn’t have a clue as to precisely how their true natures would unfold until they were already standing in front of me, their essences in full bloom.

Hurley is usually referred to on these shores as a horror novelist, but—as I hope the conversation below will show—his thematically rich work deserves to be seen on its own terms, interacting with but not bound by genre conventions. He lives in Lancashire and teaches at the Manchester Writing School.

Interview

Steven Wingate: In both your novels, “getting away from it all”—something American culture typically thinks of as peaceful and rejuvenating—instead plunges people into a deeper sense of what they can’t (or won’t) understand. What accounts for this vision of isolated geographies in your work? Is it cultural? Personal?

Andrew Michael Hurley: I like the phrase “isolated geographies.” I think that gets close to what I’m interested in. That I think of the natural world in this way is partly down to personal experience. In the remoter parts of Lancashire there are large expanses of hill and moorland where local folklore about witchcraft and hauntings still feels relevant somehow. Almost every town and village has its ghost stories. As someone who is fascinated with the (real and imagined) history of the places in my novels, it would be impossible for the supernatural not to play a part.

I think that there is a cultural element too. There is a tradition in British literature and film of finding the eerie in the remote and rural. A View From a Hill, The Woman in Black, and Sarban’s Ringstones come to mind as particularly good examples of these kinds of stories. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a raft of British films, too, like The Wicker Man, Blood on Satan’s Claw, and Witchfinder General, which presented the countryside as being a repository of primitive superstition. It was the period in which the BBC broadcast adaptations of M.R. James stories at Christmas time and commissioned original horror drama that depicted rural England as though it shimmered with malignant history. There was something peculiarly “British” about it, I guess, because much of the supernatural content stemmed from particularly British folklore and tradition. It’s come to be known as “folk horror,” of course, and I think if I were to identify with any genre or sub-genre it would be this, as it embodies a lot of what fascinates me: the otherness of nature, the weirdness of wilderness, the passing into a place where moral and spiritual certainties crumble.

I think that there is a cultural element too. There is a tradition in British literature and film of finding the eerie in the remote and rural. A View From a Hill, The Woman in Black, and Sarban’s Ringstones come to mind as particularly good examples of these kinds of stories. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a raft of British films, too, like The Wicker Man, Blood on Satan’s Claw, and Witchfinder General, which presented the countryside as being a repository of primitive superstition. It was the period in which the BBC broadcast adaptations of M.R. James stories at Christmas time and commissioned original horror drama that depicted rural England as though it shimmered with malignant history. There was something peculiarly “British” about it, I guess, because much of the supernatural content stemmed from particularly British folklore and tradition. It’s come to be known as “folk horror,” of course, and I think if I were to identify with any genre or sub-genre it would be this, as it embodies a lot of what fascinates me: the otherness of nature, the weirdness of wilderness, the passing into a place where moral and spiritual certainties crumble.

Having said that, these are ideas which are evident in other cultures too. The malevolence of a place or a place’s malevolent effect on the people who live there is absolutely at the heart of films like The Blair Witch Project, Deliverance, Children of the Corn, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The backwaters of England aren’t all that different from the backwoods of America.

In The Loney your narrator was a stranger to the natural environment, a Londoner visiting the wild countryside. In Devil’s Day, your narrator is a native of the countryside driven to return to it after living a more urban life. How did working with these voices differ for you in the writing process?

I found John Pentecost, the narrator of Devil’s Day, more interesting than “Smith” in The Loney in many ways. There was something compelling to me about his gradual rediscovery of the valley, and he developed in a way that I couldn’t have predicted, becoming more and more zealous about the place, to the point of cruelty, actually, in terms of how he treats his wife. Her needs become secondary to the needs of the farm and the community. John is more than willing to give everything away in order to be reaccepted into the “family.” He is quite prepared to believe all the stories that his grandfather, the Gaffer, told him, both in terms of folklore and the myths about the Endlanders themselves—that by being self-sufficient they are somehow inured against the rest of the world.

But what made him fascinatingly complex was that this blinkeredness, this abdication of his intellect, was partnered by a legitimate search for meaning. He finds something real and purposeful about working the land. The role that he is asked to play in the valley is simple: to be a custodian of the farm for the next generation. For John, the valley is a place of order. There are patterns and structures. The seasonal ceremonies give shape to the lives of the people there. I was put in mind of something Mircea Eliade writes about in The Sacred and the Profane—that time, for what he calls a “religious man,” operates in a completely different way to the man who has no belief in anything—that time which is punctuated by moments of ritual can be calibrated in a more meaningful way and charts a cycle but also a progression. Although John isn’t “religious,” as such, he does put his faith in an idea which makes similar demands of him. He must devote his life to a common goal, he must be loyal to the tribe. He comes to have the spurious certainty of a fundamentalist, which, for me, forms part of the horror in the novel.

The marketing conversation about your work has centered on horror (a Stephen King blurb will do that). But I get the sense, from what you’ve written in The Irish Times, that you don’t necessarily identify with that genre alone. Can you tell us a bit about your “family tree” as a writer and your relationship to genres?

I’d find it quite limiting to concern myself with trying to meet the expectations that come with a particular type of writing, and so I don’t necessarily think in terms of genre. Whether a book belongs on this or that shelf feels like a decision to be made by publishers, booksellers, and reviewers rather than me. When I hear The Loney described as being the start of a new wave of gothic horror fiction, it’s flattering, of course, but it wasn’t something that I intended to do. That’s not to say that I’m unconscious of the traditions that I’m drawing from. If I were to list some of the writers that I go back to time and again, a great many of them would probably be placed under labels like gothic, horror, weird, supernatural, eerie, and so on. I’m thinking of M.R. James, Algernon Blackwood, Robert Aickman, Shirley Jackson. But, as it is for all writers, what actually influences a piece of work comes from a mulch of pretty disparate things.

The character of Adam—John Pentecost’s son—is blind, similar to how Hanny in The Loney was mute. What is your attraction to characters who have this kind of challenge to their perception or expression?

The character of Adam—John Pentecost’s son—is blind, similar to how Hanny in The Loney was mute. What is your attraction to characters who have this kind of challenge to their perception or expression?

I guess my interest as a writer is that through them the hopes and fears of other characters are channeled. The overcoming of their deficiency is the moment when something longed for will be realized. When Hanny’s mutism is cured, this will be evidence of God’s benevolence and a vindication of all the hours spent in prayer. If John can get Adam to jump into the river, then the boy’s trust in him and all that the valley promises will be proved. There is a great cruelty, of course, in all this. Hanny and Adam have little choice about playing these symbolic roles. They are both used as proxies for other people’s anxieties and it’s them who suffer if they don’t provide the balm. They are perhaps the ones who are most damaged by the noxious power of ideas: Catholicism in Hanny’s case, the perpetuation of the Endlands in Adam’s.

We live in an age of the literary fast start, where there’s pressure to establish the stakes of a novel early on and continue raising them. Your novels take the opposite approach, starting almost luxuriously as they steep us in their atmosphere. Why do you choose that route and how does it affect your writing process?

That’s the influence of the ghost story on my work, I think. Most often, the success of the supernatural tale is predicated on the gradual building of tension and menace rather than an explosive start. It seems to me that beginning with a tremor in the background which rises to a crescendo is a more effective way of creating a sense of unease. But the “fright factor” is only one strand. I’m as interested in exploring character and location as I am in making the reader feel unsettled. For me, the setting of a novel is the novel in many ways, and it seems right to devote time and space to establishing the geography and history of the place. This forms a frame inside which the rest of the story takes place.

You do an interesting thing with time in Devil’s Day, gently shading in both the past and the future. For instance, we know that John Pentecost is living in the Endlands with a blind son from early on, though we only learn the logistics of these facts gradually. You do similar things with the past (like what happened to Lennie Sturzaker). Why are you attracted to this strategy, and are there authors you’re borrowing it from?

The management and manipulation of time in Devil’s Day was probably one of the most difficult tasks. I don’t know if I was attracted to the strategy, as such. It came from necessity. As the novel developed, I began to understand how past, present and future were interconnected and ever-present in the valley. The farmers were always looking backwards and forwards. It was what underpinned their communal identity, in fact. So, it was impossible to tell the story without this palimpsestic layering of time.

At one point you gave up teaching and worked in a library to commit yourself to writing. Can you talk about that moment of commitment—how you knew the time was right and how you knew (if you knew) that you were up to the task you’d set yourself?

It was something of a gamble, I have to say, because there were so many unknowns. The main one being that I had no idea if I was going to be able to write a novel at all. I’d written short stories up until that point and while there are certainly some skills—precision, brevity of expression, and so on—which can be carried over into the novel, they are quite different beasts. I suppose that I was only confident that the time felt right. My mother had just passed away, at a fairly young age, and it was hard not to feel as though I ought to be using my life well from that point on.

You started your career with a tiny printing of The Loney—three hundred copies—and now you have a major release not only in the UK, but across the pond. It’s a writer’s fairy tale, a success story that just about all of us hope for. Can you talk a bit about the journey from then to now? And if you could distill what you’ve learned into one piece of advice, what would that be?

You started your career with a tiny printing of The Loney—three hundred copies—and now you have a major release not only in the UK, but across the pond. It’s a writer’s fairy tale, a success story that just about all of us hope for. Can you talk a bit about the journey from then to now? And if you could distill what you’ve learned into one piece of advice, what would that be?

It’s almost four years now since Tartarus Press first published The Loney, and I still find it genuinely surreal what’s happened. I don’t take any of it for granted. I don’t feel entitled in any way. I don’t think many writers do. Finally achieving what you’ve been working towards for years is as fragile as anything that’s hard won. It’s a privilege to be able to write books for a living and being able to carry on doing that has been the best outcome of success.

Two words that I try to remember are Love and Patience. First and foremost, write because you love to write. That should always be behind what you’re doing. It’s what will prevent you from actually giving up when you feel like doing so. Don’t lose sight of the joy of putting words on the page and understanding the world just a little better than you did before. Write for you first; and, if you want to write for others, be patient. Get to know your voice. Learn your craft. Fail. Expect it to hurt. Do it better next time. Walk all the streets you can find, including the blind alleys, rather than taking the short cuts, or staying at home. Allow yourself the space to improve. Allow yourself to think about what you’re writing whenever you can. Don’t feel guilty. Don’t ever think that what you’re doing isn’t valuable. No writing or time spent writing is wasted.