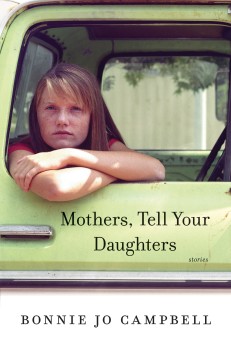

Bonnie Jo Campbell’s new collection of stories, Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, will surprise and delight readers who are familiar with her work, and draw in those who haven’t yet had the pleasure. We find some characters who would have been at home in the world of Campbell’s previous books: men and women of working-class rural Michigan, who, when life gives them lemons, throw them back again as hard as they can. Campbell also takes the reader to new territory—to a circus train parked in the Arizona desert in one story, and in another, to the Romanian countryside, where a woman falling for her local tour guide prays to give birth to “wild creatures…stronger than dictators.” The recurring subject of the collection is, as the title indicates, the bond between mothers and daughters, whether strong or weak, enduring or transient. It’s the relationship that can’t be forgotten or evaded; that must be explored, analyzed, reinterpreted, over the course of a lifetime.

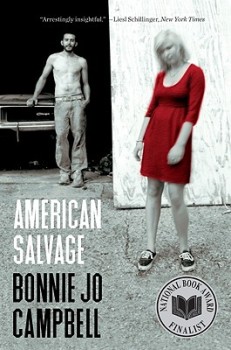

Bonnie Jo Campbell has published two earlier collections of stories, American Salvage and Women and Other Animals, and two novels, Once Upon a River and Q Road. American Salvage was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Once Upon a River was a national bestseller and a Michigan Notable Book. I spoke to her in April at the 2015 AWP Writers Conference in Minneapolis, following her panel presentation on “Hick Lit: Women Writing from the Circumference,” with Claire Davis, Adrian Blevins, and Diane Seuss.

Bonnie Jo Campbell grew up on a farm in rural Michigan. She lives outside Kalamazoo with her husband, donkeys, and other animals, and teaches fiction in the low-residency program at Pacific University in Washington.

This interview, part of a series of conversations with writers of rural fiction, is conducted in partnership with The Art of the Rural.

Interview:

Mary Stewart Atwell: One thing you said at your recent AWP Writers Conference panel that I thought was really great was this idea that literary fiction shouldn’t be based around a nostalgic take on the rural. Looking at the rural through this lens of sentimentality isn’t really fair to the people who live there. Maybe another side to that is that readers might resent it if the rural isn’t presented in terms of stereotypes, like a country song…. So I’m wondering if you’ve ever gotten that response from readers—like, This isn’t the country as I think it should be?

Bonnie Jo Campbell: That’s a good question, but surprisingly, I don’t think I’ve gotten a serious negative response of that type. And maybe it’s because of the way the books have been labeled—that they attract literary readers rather than readers in search of nostalgia. But I will bet that some people, maybe even in my hometown, have picked up my book and been disappointed in exactly that way. Those of us who are from rural areas know that neither nature nor farming are actually as peaceful as people want to think they are, but plenty of people want to keep alive that illusion, for example, that farming isn’t a violence against nature. We know it is violent, that it’s a necessary violence against nature.

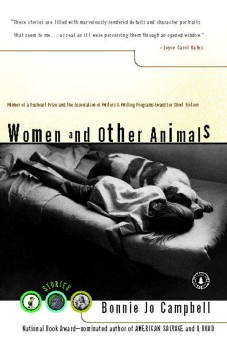

Though I never shy away from the positive, I do follow the old rule that trouble is more interesting than the lack of trouble. That said, I do try to write about what’s beautiful and what’s good in nature. Maybe more so in my first book, Women and Other Animals (University of Massachusetts Press, 1999). The women and girls in that book take a lot of comfort from the farm and from natural spaces. American Salvage (Wayne State University Press, 2010) is different because it’s about men, and the kind of men whose lives are maybe more associated with machines than with nature. In those stories, men are being asked to make a transition to the new information age and to leave their machinery behind. If I was going to write another story for that book, I’d probably write about the issue of farming in the city of Detroit—some are suggesting that Detroiters should become farmers, but there’s a lot wrong with that plan. In Once Upon a River (W.W. Norton & Company, 2011) I wrote about a protagonist who is actually a physical embodiment of the river—that’s what I meant Margo Crane to be to some degree. I also meant her to be a flesh and blood girl, but I enjoyed exploring what a girl would be like if she embodied the characteristics of the natural space she loved, which in her case was the river.

Though I never shy away from the positive, I do follow the old rule that trouble is more interesting than the lack of trouble. That said, I do try to write about what’s beautiful and what’s good in nature. Maybe more so in my first book, Women and Other Animals (University of Massachusetts Press, 1999). The women and girls in that book take a lot of comfort from the farm and from natural spaces. American Salvage (Wayne State University Press, 2010) is different because it’s about men, and the kind of men whose lives are maybe more associated with machines than with nature. In those stories, men are being asked to make a transition to the new information age and to leave their machinery behind. If I was going to write another story for that book, I’d probably write about the issue of farming in the city of Detroit—some are suggesting that Detroiters should become farmers, but there’s a lot wrong with that plan. In Once Upon a River (W.W. Norton & Company, 2011) I wrote about a protagonist who is actually a physical embodiment of the river—that’s what I meant Margo Crane to be to some degree. I also meant her to be a flesh and blood girl, but I enjoyed exploring what a girl would be like if she embodied the characteristics of the natural space she loved, which in her case was the river.

That relationship was obviously such a big part of the book, but I never thought of her as being sort of a river spirit.

In the very first pages I have her grandfather calling her a river sprite, just to make that suggestion gently. When you’re writing, it’s always kind of fun to lay those little clues in there, whether it’s just for yourself, or whether the reader picks them up unconsciously.

Once Upon a River began as a short story, “Family Reunion.” How did you know that that story wanted to become a novel? How did you go about shaping the material into a sustained narrative?

When I was writing “Family Reunion” I had no intention of writing anything beyond a short story. I sometimes say that my novels are really just failed short stories; I try to wrap a story up in twenty pages or so, and if I can’t, then it might turn into a novel. I thought that I had come up with a perfect ending for “Family Reunion,” but gradually I realized that its perfection was an illusion. If a girl shoots the end of a man’s pecker off, the trouble is not over—the trouble has just begun. When I realized I had a lot more to say about Margo Crane, when I saw glimpses of her in several of my other stories, I realized I had a bigger story to tell. After a couple of years of work, I was sure I had a novel worth telling.

What you said about Margo being associated with nature and the men with machinery made me think about what’s going on with masculinity in your stories. Do you feel like in that rural landscape there’s somewhat of a crisis with men knowing how to be men?

Could be. What inspired a lot of the stories in American Salvage was the observation that many of the men around me were not making the transition gracefully from the industrial age to the information age. I was interested in how some men in my hometown expected that their lives would be a certain way, that they could get by without a lot of education, that they could get by the same way their fathers got by, by working in factories, by being good, loyal workers, and when they discovered that this was no longer the case, they had nowhere to turn. Whether it’s particularly a phenomenon that’s really happening nationwide, I don’t know, but I did see that a particular kind of rural or small-town man was having trouble. In American Salvage, there are a couple of stories about the Y2K phenomenon. As the year 2000 approached, some men saw a disaster of Biblical proportions approaching, and it seemed a natural outcropping of their anxieties about their lives.

Why women are adapting so much better is another question.

Well, I think women have always adapted to men, have adjusted to men’s needs, and maybe that has kept them a little more open-minded about what will happen next. Plenty of men are doing just fine, of course. My stories are only addressing a minority of men and women.

Your story “The Trespasser,” in American Salvage, deals with a collision between a family with a summer home and the locals who take it over. Does this tension between the community and out-of-towners reflect a reality you see in northern Michigan?

That works! Originally I was interested in comparing two teenage girls, one who has lived a relatively privileged life and, well, another who hasn’t had many advantages—I can hope that two teenage girls can find an understanding of one another even when adults cannot. I was also interested in turning righteous anger on its head, in particular the righteous anger one feels when one’s home is violated. For fun, I was also retelling the Goldilocks tale, in which a golden-haired girl breaks into a home and samples the goods. Finally I was interested in exploring the sexual element, as it sometimes arises in conjunction with methamphetamine abuse. It is absolutely a story about class differences.

In the story “King Cole’s American Salvage,” you seem to know a lot about stripping cars. In “Boar Taint,” Jill has picked up a lot of knowledge about farming, but views it from more of an academic perspective. Which of these points of view is closer to yours? Do you do a lot of research for your fiction, or do you tend to write about things you already know about

Basically, I learn whatever I need to know, and I learn any way I can. I usually start writing about something I know something about, but then end up over my head and in need of research data. It is all about serving the story. I’m always glad when a story needs some information that I already know (say, about donkeys or blackcap raspberries or bicycling), but it doesn’t always happen that way. Occasionally I’ll learn about something new and be so inspired that I write about it; once I found a Luna moth and tried to feed it, only to discover that they have no mouth-parts, that they never feed, but only breed and die. More often, I’m writing a story and I realize I have to know more about this thing in order to make the point of view seem realistic. For example, I already had some knowledge about pig farming and scrapping out cars, but I needed more nuanced information to fit it to my characters’ ways of seeing, both from talking to people and doing research in books and online. In Once Upon a River I had to learn a lot about shooting. I learned about skinning muskrats from my mother and from YouTube videos.

One of my favorite stories in your new collection, “The Greatest Show on Earth: What There Was, 1982,” takes place entirely on a circus train in Arizona, and features a relationship between a down-on-their-luck couple, Buckeye and Mike, who sell candy and snow cones and shoot speed on the side. Another takes place at a wedding in Transylvania. These feel like such a departure for you, in terms of voice and subject matter. Did you set out to explore new territory with this collection?

Both of those are stories I started a long time ago, but kept working on for years. I used to travel with the circus, and I did spend time traveling in Romania, so those rely on my own autobiographical elements about as much as the stories that take place in Michigan. I didn’t intentionally leave my home turf, but was willing to travel wherever I needed to go to serve those stories, to figure out what I needed to make them meaningful. I am pretty open minded about where my stories take place, but I choose the familiar venue if that one lends itself.

The story “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” showcases a generational divide between a mother who “for years…warmed [her]self in borrowed skins of men” and her daughter, a professor of Women’s Studies who seems unable to understand her mother’s choices. Do you see this sad sense of separation between parents and children—between people who have left, and people who have stayed—in your own community?

The story “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” showcases a generational divide between a mother who “for years…warmed [her]self in borrowed skins of men” and her daughter, a professor of Women’s Studies who seems unable to understand her mother’s choices. Do you see this sad sense of separation between parents and children—between people who have left, and people who have stayed—in your own community?

“Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” was the final story I conceived, and I wrote it specifically to fit into the collection. I loved writing it because I love showing the clash of cultures that can occur over time within a family. I wanted to show the richness of something we could call family values! The mother grew up in a time and in a manner for which the focus had to be on survival. The daughter has had more opportunities, and her more privileged life has allowed her to focus on her mother’s inappropriate parenting. I don’t see so much of this is my own family, because we are tolerant of one another’s curious ways of living, but I see the seeds of these attitudes. Maybe this is a variant upon what immigrant families experience, when each generation faces different challenges, and often profoundly disappoints the generation preceding it.

A lot of these stories present women who have survived trauma—rape, domestic abuse—and some include women who seem to have colluded in the physical and sexual abuse of their own children. When in the process of writing these stories did that theme emerge? How does the collection as a whole speak to the subject of abuse and how people respond to it?

Oh, gosh, what a can of worms! Abuse is everywhere. Abuse is perpetrated by some upon others, and then there are a whole slew of other people who are witnesses, apologists, and those to whom the abusers and abused people vent and react, until we are all tied in knots around the actions of abuse and neglect. I don’t feel able to make any generalizations overall, beyond showing readers a few versions of the trouble and showing how a few characters are reacting and taking action on this and moving forward. I guess I have always been interested in stories of rape and abuse, but I have often shied away from these stories because I don’t want to write about women as victims, and when I have decided to write the stories, I’ve probably have varying degrees of success. Readers are more ready to see women and girls as victims. By this I mean, consider Huck Finn—nobody considers Huck a victim though he has been abandoned and abused by his family and society. I want my female characters to have the same chance Huck has to be the prime actors in their own stories, even when they are victims of rape and other abuse.

After that, the book ends on a very different note, with another of my favorite stories, “The Fruit of a Paw-Paw Tree.” The point of view character, Susanna, seems at first to think she’s beyond the age when love is a possibility, but then she falls for an air-conditioning repairman named Wendell, who introduces her to the paw-paw. In the last paragraph, Susanna wonders “how on earth she had lived without this fruit all these years.” Why did you choose to place this story at the end of the collection? Was it important for you to leave the reader with this image of a bittersweet hopefulness?

I originally wrote this story to feel like an essay, in the Lake Wobegon style of storytelling, and maybe that’s why it ended up with a more light-hearted, positive tone. My readers know that I’m very interested in farmwomen, including those of the rugged and tough variety. When women have spent their lives focusing on survival, they often have become tough to the point of losing their sensitivity or even sense of fairness. To survive and raise families they’ve sacrificed some part of themselves. However, I saw that this woman, Susanna, named after my mother, was ready for a change. She was opening herself up to possibility by showing kindness to a neighbor boy and a baby donkey. This is how I see all my characters, as opening themselves up to something new, something a little better, but Susanna seems particularly likely to succeed in finding happiness. That seemed like a good place to end the book.

At the AWP panel, you also said that “The rural is about survival, not the American dream.” It seemed to me that you were saying that these people are about not ascension, but consolidation—hanging on to what you have.

I was speaking about my own community. I’m interested in the way people cope when they have problems and predicaments that have no solution. In my community, folks aren’t usually thinking about how to get ahead or even how to get money in the bank—they’re more often thinking about how to pay the bills and how to give their kids what they need right now. As educated people, we can feel sad about the kinds of folks I write about because they are missing out on a lot of opportunities, but they’ve got kids to raise and they’ve got bills to pay, and maybe there’s some way in which these folks are liberated by not being obsessed with getting ahead and ascending the social ladder. Every day I see very hardworking, busy young women, working long hours for low wages and raising children at the same time. These women do without many resources, but there is plenty of joyfulness in their lives. These women are enjoying life with many difficulties, and I don’t know if people are so much better off when they’re always striving to achieve and succeed—that’s like working overtime. On the other hand, I worry about what will happen in the future for such women and men, because it’s no fun to have medical problems and bad teeth they can’t afford to fix.

I know and love a lot of people who don’t read literary fiction. Some of them will read my stories, because they love me, but they don’t read literary fiction as a rule. I’ve wondered if it’s because literary fiction presents new challenges, and when people are focused on their survival, they have enough of those challenges already. Maybe when their lives are difficult enough, they don’t want their literature to provide abstract difficulties. Maybe it makes sense for some people to prefer escapist literature like romance novels and mysteries, where a happy ending is assured.

I heard an interview not too long ago with a writer, whom I won’t name, who seemed to be saying, “I want to write books that people in my community would want to read, because most literary fiction, they wouldn’t understand.” I was troubled by that, because the country people I know are also some of the smartest people I know.

It’s not a matter of intelligence. To some degree it’s a matter of taste. It’s a matter of interest, and how you want to spend your free time. For people who are exhausted and just trying to get by, the choices might be different than for the average literary reader. Take my mom. When she was raising kids and struggling to get by, she read mostly mysteries—she used to avoid any book that said “a novel” on the cover. Now that she’s more relaxed and her situation is more secure, she does read a lot of literary fiction.

So now that you have had a lot of success, and education that the people around you don’t necessarily have, do you—

Well, many of the people around me have plenty of education. In my immediate family, most people haven’t gone to college. Everybody in my family accepts each other’s eccentricities, and my eccentricity is that I’m educated. Maybe they think it’s just a weird thing that I’m doing. I am close friends with people of all levels of education.

At the panel, someone asked a question about race, and you said, “We should do another panel about that,” and—

Well, at lunch we’d been talking about how race and rural issues intersect, and I admitted that I wasn’t sure what I could say on the subject. I’m very cautious about co-opting the stories of other people’s lives, and I’m mostly comfortable writing about the white people I grew up with. I do feel that my work lacks racial diversity, and I’m not sure how to address that. My work presents diversity in age, and in point of view, even sexuality. I’m very comfortable writing from a male point of view—in fact, I find it easier to write from a male point of view.

A statistic came up at my panel that only six percent of the rural population is of color. It’s just another way that the rural may in certain ways seem to be out of touch with the rest of America.

For starters that means we need to get that six percent right. One thing I can address in my stories is the fact of the racism of some of my characters. Some of them prove to be racist, and I struggle with how to take that on in fiction. I’m confounded in real life when I encounter a situation where someone exposes a racist attitude, but in fiction at least I have time to ponder it, and I don’t shy away from it or wish it away, as it might when it happens in real life.

For starters that means we need to get that six percent right. One thing I can address in my stories is the fact of the racism of some of my characters. Some of them prove to be racist, and I struggle with how to take that on in fiction. I’m confounded in real life when I encounter a situation where someone exposes a racist attitude, but in fiction at least I have time to ponder it, and I don’t shy away from it or wish it away, as it might when it happens in real life.

In a story of yours that I teach from American Salvage, “The Burn,” my students always talk about that. One of the moments when I really love in that story is when the main character, Jim, lets out a shout that wakes up people in an upstairs apartment, and he starts imagining their lives and has this real moment of empathy and connection, but then immediately suppresses it. You can see that urge in him to put himself in other people’s shoes, and how he’s not allowing himself to do that.

In that story, I wanted to show that not everybody who behaves in a racist way is a hopeless racist. I mean, the protagonist is a racist, but a lot of that comes from his bring afraid to think for himself—he’s afraid that his own friends will reject him for having an open mind about people of color and the lesbians upstairs. And maybe I am making a comment about a certain kind of male culture that is a little more common in rural areas, where there are fewer alternatives to the community one is born into. I felt that in this character’s life, he was saddled with some limitations, resulting from limitations in what he had been exposed to. And I did think that there was hope for him to become a better person.

Oh, good. I was going to ask you whether you imagined continued lives for your characters, because whenever I read that story I think, “I want something good to happen for him.”

Oh, yeah. I imagine that there’s hope for that guy. You know, him talking to his neighbors would be a start. Just talking to people a little bit more can open up a frightened mind. I don’t necessarily investigate the lives of my characters beyond the stories, but I have hopes for them, hopes about what could happen.