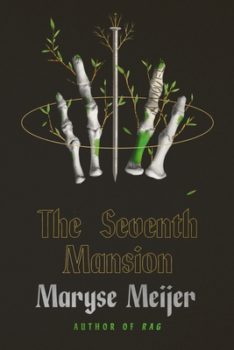

I’ve admired Maryse Meijer’s writing since I read her 2016 debut collection, Heartbreaker (FSG), and was delighted to make her acquaintance last year when we were introduced by a mutual friend. At the time, Maryse was doing research for a memoir about bullfighting and animal rights. She was also working on final edits for her debut novel, which she described to me as a story about a boy who falls in love with a skeleton.

Now reading The Seventh Mansion (FSG), I’m struck by the depth of feeling in a narrative that veers from social and political concerns to the deep and bodily intimacy that the protagonist, Xie, a teenage vegan and radical, experiences with the relic of Saint Pancratius. Meijer’s plots often hinge on desire and questions of power, and these concerns are on full, lusty display in this story about experiencing solitude on the social margins but connection with the natural world.

For this interview, Maryse and I talked on the phone and via email as COVID-19 numbers started to rise in Chicago once more. Keep an eye out for information about Maryse’s online events this fall, where you can be in touch with her since she generally eschews social media in favor of letters and exchanges of ideas and art.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: The Seventh Mansion is your first novel, but it’s your fourth book in four years. In addition to your two story collections, Heartbreaker (2016) and Rag (2019), Catapult published your novella Northwood (2018), which in some places is referred to as “a poetic novel-in-fragments.” Could you talk about the continuum of work for you with these four projects? Were they in dialogue? Did you pause in working on one to focus on another?

Maryse Meijer: I usually work on several projects at a time. Thematically they are all concerned in some ways with loneliness and desire. But I think those themes mutated as time went on—I became less interested in the dissolution and destruction of connections and more interested in the restorative nature of desire.

In this novel, Xie and his romance with the skeleton of martyred saint Pancratius is the emotional heart of this work. However, the story is driven by commitment to animal rights and ecology activism, as well as community and social hierarchies. I found the tension between Xie’s solitude and intimacy with the relic, and the social aspects of ostracism and activism in his high school and community, so palpable throughout the novel. Where did Xie’s story begin for you, and how did it evolve?

For many years I had wanted to write a novel about a boy who was obsessed with bones, a kid who had had some troubles with school and had some kind of secret life. At first I had the idea it might be a young adult novel—I’m not sure why—but I realized that I wouldn’t be able to be as explicit in that genre as I normally am, so I abandoned that idea for a while. Then my twin sent me a photograph Paul Koudanaris took of the relic of Pancratius—this skeleton dressed in a fantastic suit of silver armor—and I knew that I had to write about that body, and that this boy who had been vaguely swimming around in my head was the lover of that body, and slowly Xie took shape. I had this sense of this posture he had, this really skinny kid with hair in his face who was sort of outrageously sensitive to everything, who had a great capacity for loneliness but also an equally big capacity for connection. And I think when I saw the relic, I realized the love for bodies like that had something to do with animism, with the idea that all things are, in some ways, alive—a notion that most of us have as young people, before everything becomes a mere object. I kept seeing Xie in the woods, surrounded by trees, and there was some kind of parallel romance going on there, with all these different forms of nature. So there was this incredible Catholic body and this boy and these woods, and I was always reading about animal activist stuff and how sometimes actions go all wrong—like what happens in the book with the mink Xie and his friends free on the farm—and I kept thinking about how deeply failure is etched into activism, and life itself, and the incredible effort it takes to push through that on a daily basis, and there was Xie, with that defeated but defiant sort of posture, someone hiding himself from the world but also really radically trying to be in the world, someone who understood the ecstasy and the misery of trying to live a life devoted to something other than oneself. When I went through my Catholic phase growing up, I was obsessed with saints, with martyrdom, and Xie appeared to me as a kind of modern-day saint, which meant he had to be an outsider, he had to have this relationship to desire that was almost religious, and mysterious, and kind of fucked up. But it really started with this interest in people who love dead bodies and how that might have something to do with loving nature.

You touch on several aspects of your process here. I understand that your twin Danielle is often your only reader as you revise, and The Seventh Mansion is dedicated to her. Yet you were clearly thinking about potential readers too (e.g., YA necrophilia might not play so well). What roles did potential genre and audience play in writing this novel?

I thought more about the elements of horror that run through my work, and how growing up I was reading a lot of genre, and watching—as I still do—a lot of horror films, and how writing is, for me, a place to be scared, and a way to sort of write myself out of being scared. So I was thinking about what makes horror horrific, and thinking about this idea of reversal, like taking the thing that would normally be used as the source of horror in a story—in this case, the presence of a dead body and its walking, talking spirit—and normalizing that in some way, making it something definitely strange but not disgusting or evil or “bad,” and then taking a sort of everyday reality—the destruction of nature—and letting that appear as the source of horror. I’ve said elsewhere that there are many aspects of daily life under patriarchy and capitalism that are utterly horrific, and I think that mindset is reflected in my work, and I think readers and reviewers have rightly identified that element of the horrific and its connection to what we call genre.

I think writers can get away with a lot of stuff under the guise of writing “literary” fiction—there are lots of people who wouldn’t pick up a book categorized as horror—but there are plenty of books that get billed as mainstream that are more intensely horrific than anything with a label. I don’t think categories are generally all that useful, but there are ways maybe we can use them or subvert them in critical ways that can help us think about the categories themselves. A lot of people seem to want to talk about Mansion as a “coming of age” novel, which bums me out—like, what does that even mean? Coming of what age? As if writing about young people means that your audience is either YA, or the audience is a group of people who are going to feel superior to the protagonist, who are going to frame his experiences and feelings as part of some “phase” or something equally ridiculous. Xie is sixteen, yes, but his youth isn’t the point of the book. It’s not about him “becoming” an adult or more wise or more of a person, just as the adult characters don’t exist as examples of adulthood as a particular way of being.

When I had thought of writing a book specifically for a YA market, I wanted to do so in the hopes of writing something that was really no different from any of my other work in terms of the explicit nature of the material—I thought it would be interesting to try and infiltrate that genre, because I think young readers need more serious books that don’t patronize them, books that speak to the crazy stuff we all have going on in our heads, at every age. But I realized that would just be an excuse for marketing to limit the readership for the book, which would have undermined the whole point. Yet why have all these pre-determined ideas about who the audience for a book is at all? I still read picture books. Some of the greatest literature being made right now is marketed to people under ten, and it’s a shame because adults should be reading those books, too, and not just to their kids. When I was ten, I was reading Harlequin romance novels and Anne Rice and biographies of serial killers—those books weren’t “for” me, but they were what I wanted to read; I related to them in ways the people publishing those books could not have anticipated. It’s all just a big jumble. We want different stories for different reasons, and the categories don’t do as much work as they think they do. So if I’m thinking about audience when I’m writing, it’s about trying to write for the reader who gets lost through the cracks of genre and marketing and all of that, and thinking about how best to reach those readers, and sometimes you have to manipulate categories to do that.

I’m also curious if, as beliefs and practices, veganism and environmental activism influence your writing—and how.

I think the vegan thing is about wanting to find a way of life that is pure. Which is not possible, of course, but it was a response to feeling overwhelmed by a lot of different things—violence and suffering and my guilt about my role in all of that. I did some protests and spent a couple years wanting to be like the activists in my book, but I was too scared or lazy or confused to do it. It’s easier to write about other people doing it so that’s what I did. I’ve never done a single thing for animals or for the environment that was meaningful. I think in my writing I let people be worse than me and better than me and it’s a way to work out the desires to be both. Perhaps it is also quite cowardly. People often talk about how writing about certain subjects is “brave,” but, really, I don’t know what that could possibly mean. In some ways this book was a slap to my own face, me taking myself by the shoulders and telling myself to wake the hell up. I “know” a lot about environmental crises and animal and human suffering, I’m obsessed with these ethical questions about how to live a decent life, but at the end of the day I live a completely complicit existence, regardless of what I eat or how many trees I (literally) hug. My veganism is an easy choice, as is my token concern about environmental issues. My own activism has demanded so little of me because I have always been afraid of the demands of my ideals. The goal of living in absolute terms according to one’s faith or ideals, whatever they might be, seems important. But I have failed to do any of that. I have given myself up instead to writing, which is a decision to live in a fantasy world, a decision to devote myself to an artistic ideal that spares me the trouble of grappling more viscerally with the meat of my own existence as it is lived within all these institutions I despise but still more or less participate in.

I think the vegan thing is about wanting to find a way of life that is pure. Which is not possible, of course, but it was a response to feeling overwhelmed by a lot of different things—violence and suffering and my guilt about my role in all of that. I did some protests and spent a couple years wanting to be like the activists in my book, but I was too scared or lazy or confused to do it. It’s easier to write about other people doing it so that’s what I did. I’ve never done a single thing for animals or for the environment that was meaningful. I think in my writing I let people be worse than me and better than me and it’s a way to work out the desires to be both. Perhaps it is also quite cowardly. People often talk about how writing about certain subjects is “brave,” but, really, I don’t know what that could possibly mean. In some ways this book was a slap to my own face, me taking myself by the shoulders and telling myself to wake the hell up. I “know” a lot about environmental crises and animal and human suffering, I’m obsessed with these ethical questions about how to live a decent life, but at the end of the day I live a completely complicit existence, regardless of what I eat or how many trees I (literally) hug. My veganism is an easy choice, as is my token concern about environmental issues. My own activism has demanded so little of me because I have always been afraid of the demands of my ideals. The goal of living in absolute terms according to one’s faith or ideals, whatever they might be, seems important. But I have failed to do any of that. I have given myself up instead to writing, which is a decision to live in a fantasy world, a decision to devote myself to an artistic ideal that spares me the trouble of grappling more viscerally with the meat of my own existence as it is lived within all these institutions I despise but still more or less participate in.

There’s also the reference to an anarchist badge early in the novel—and I understand that’s a badge you actually wear on your coat.

Yes, putting that patch in there was a way to connect myself to Xie in some way, a little thread connecting the two of us. I think more than being vegan or thinking about environmental issues, my anarchism has affected my writing the most because it has informed so intensely my ideas about violence on every level. I want to approach my work with an anarchist spirit, to keep finding ways to break myself of the habit of relying on certain narrative strategies that aren’t really that useful to me, ideas about what writing “is” that have been inherited but not sufficiently interrogated. And in terms of subject matter I like to look at ideas and feelings and relationships that are bound up in violence because I think all these little domestic forms of violence reflect and mimic institutional and structural violence enacted politically all around us, all the time, and maybe if we ask ourselves why we hurt ourselves and each other we can also ask who is hurting us and why.

For me, anarchy is about love, about a radical approach to the ideas of loving Others, human and otherwise. It’s about community. When I was writing this novel, I wanted to engage with my own optimism and idealism about the possibility of connection and regrowth in the face of mass extinction and mass suffering by writing about people who had more interesting things to say and do about those things than I. And I also wanted to look at some of the problems of devotion to so-called radical principles, the ways it can make you shut down, turn away from other people, because you feel so alone in the way you think and feel, or you feel threatened or misunderstood or even crazy, sometimes. So I wanted to deal with all that difficulty but also make the book essentially safe, a place to be vulnerable, idealistic, lonely, crazy, without judgement.

I love your use of sentence fragments—the movement they lend your work. For example:

They had parked Jo’s car in the lot of an abandoned Waffle House and walked on foot, 1:00 a.m., to the Moore farm. Head to toe in black. Heavy gloves. Knit masks tight and hot on their hesds. At the base of the mountains hardly any houses. No light on at the Moores’; easy to slip to the back, skinning beneath the windows. Do they have guns? Leni whispered. Of course they have guns, Jo scoffed, they all have fucking guns.

When I read this aloud, the fragments have a kind of hushed, gasping effect that scores the action of the scene: Xie, Leni, and Jo sneaking onto the farm to free the minks. What is your process in working with fragments, rhythm, and sound in prose?

As soon as I started writing the novel I had this fitful voice in my head. It was much more extreme in the first several drafts, with everything chopped up into tiny, tiny fragments. Maybe out of fear or for good reason, I smoothed it out quite a lot in subsequent drafts. Xie has so much anxiety, and he’s so stressed out about everything, and he can’t bring himself to really think about his own sexuality or his feelings in a sustained way, so it’s all broken up in his head. I wanted a different kind of stream of consciousness—not one that flows and rambles on, but that gets all choppy and ugly. I think it stops you constantly, the way Xie is always stopping, in his mind, getting stuck. But he is also very, very aware of everything, and so there’s a clarity there, too. I wanted to be stuck in his body, be ultra-present, which meant that the diction had to constantly interrupt the desire to just read normally. But then there is a certain rhythm you get out of fragments, a kind of music that I really like once you get into the swing of it, once you start really hearing it in your head. And then when you want to be lyrical and run on and let things be loose and more superficially beautiful, you have this chunky sort of skeleton to hold all those moments down. When Xie gets overwhelmed, for better or worse, the language does, too. And I kept thinking it was like blood moving through a body, and that was the thing that Xie really is scared of—of being alive at all, of the terror of having to decide how to live. But when he just lets himself be present, or is forced to be present, then it’s like letting the body take over and do its thing, pumping the blood through the tissues, according to its own consciousness. The book wanted to have its own consciousness, to sort of work independent of my usual aggressively micro-managed language. I think working on a computer sort of does this to you—it makes you think like Xie, it makes you a bit confused and micro-focused. Writing by hand is a lot more relaxing. So when I wanted to let Xie relax, or I wanted to feel P.’s influence, I didn’t work with a screen. And the changed rhythms because of that I thought seemed right. But then you edit and edit and it all gets fucked up and micro-managed anyway, so who knows. You have a lot of nice, lofty ideas about what you’re doing at various stages of writing a book, but in the end you realize you’re just desperate and you have no clue about any of it or what your intentions were or how it worked out. And then you have to make some sort of sense in an interview, so you scramble around for a narrative. But really, I never truly remember where the voice of a story or novel comes from. The only way to explain it is to say that a story just comes out a certain way and then you either follow it or you don’t.

You aren’t on social media, but you have a rich, thoughtfully cultivated artistic community in your life through letters and exchanges of music, words, and art. You have celebrated so many other writers’ books by throwing cocktail parties in your home. And yet, here we are, your debut novel arriving, and we can’t celebrate it in person as we might. So how are you marking the occasion? And how are you moving forward with your work through the pandemic?

When I have a book coming out, I like to connect with people who have inspired the work in some way, and I like to write to my readers. For example, you mentioned the patch I wear on my jacket that made its way into the book; that patch was made by the amazing Matt Gauck, who sells his stuff on Etsy—my jacket is covered with patches from his shop, and I’ve loved wearing his work and been inspired by it. So I wrote to him asking if I could send him a copy of the novel, and we exchanged some emails and FSG ended up buying some of his work to send out with their publicity packages, which I was thrilled by, and I bought a bunch of his stuff to send out to friends as well. And I found out that Matt is just as awesome and wonderful as I’d imagined he was—he’s a true kindred spirit—and it felt really good to get to know him, to thank him for his work, and acknowledge his influence.

And I recently exchanged correspondence with a couple of readers who posted things about my work and discovered that one, Barry Paul Clark, is an incredible musician working on several projects, one of which, adoptahighway, has been providing me with some great music to listen to while I write; and I had the privilege of reading the work of a young bookblogger in Bristol, Molly Llewellyn, who sent me a story that just blew me away. So while I love events and parties and seeing people face-to-face, I’ve managed to find ways to keep building that community from home. It reminds me that I don’t exist in a vacuum. And I just keep writing because that’s what I love to do.