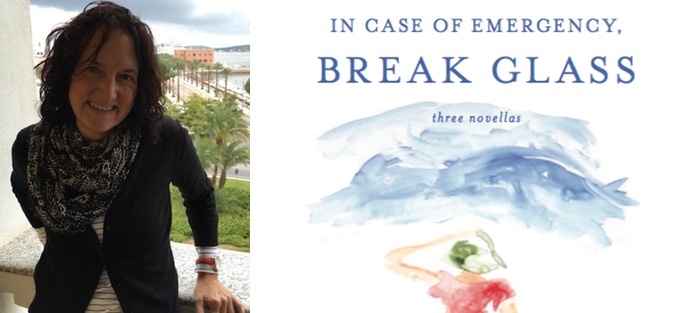

In Case of Emergency, Break Glass (Queen’s Ferry Press), is a collection of three novellas by Sarah Van Arsdale. The three stories are linked by the themes of travel, and the disruption to identity that travel can bring. Two of the stories are about American women traveling in Europe. The third, “The Sound in High Cold Places,” is markedly different, and different from anything else Sarah has written: it’s set in Arctic Greenland, at a time before the encroachment of European explorers.

What I admire most about Sarah’s writing is her keen eye for setting, and her use of poetic language. Setting is important in my own work, and so I know when a writer is really using setting and when something is just placed in the most convenient location. Sarah pushes her settings to work as characters in the stories, with the effect that I cannot imagine them taking place in any other time or place. She makes use of her deep knowledge of poetry in describing these settings; it’s no surprise when she tells me that her mother recited Gerard Manley Hopkins and other poets while she was growing up.

Sarah and I met at the Ragdale Foundation residency in 2005. We were fortunate enough to be part of a residency group that bonded tightly in our two weeks together; most of the group stayed in touch for years after. Sarah and I became close friends over the years since then, widening our writers’ friendship to include all the elements of life, though we still often talk together about our writing and writing process.

In addition to this new book, Sarah is the author of three previous novels: Grand Isle (SUNY Press, 2012); Blue (University of Tennessee Press, 2003), chosen by Alan Cheuse for the 2002 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel; and Toward Amnesia (Riverhead Books, 1996). Her next book, The Catamount, a long narrative poem, will be published in 2017 by Nomadic Press. Both this forthcoming title and In Case of Emergency, Break Glass are illustrated with her watercolors. Sarah has also received residencies at the Hambidge Center, the Jentel Artist Residency Program, the Djerassi Resident Artist Program, and Playa Summerlake. She serves on the board of the Ferro-Grumley Award in LGBTQ Fiction, and teaches in the Antioch University MFA Program and at NYU. She is curator of BLOOM: The Reading Series at Hudson View Gardens.

Interview:

Natalie Baszile: First let me say, I love your writing and thoroughly enjoyed the book; it’s lovely. What struck me immediately about your first novella, “The Sound in High Cold Places,” were the characters. They’re nothing like I’ve ever seen before. Why did you want to write about First People?

Sarah Van Arsdale: Thanks, Natalie. I started “The Sound in High Cold Places” about twelve years ago, a few years after I went to the Arctic. It was serendipity that brought me there; I didn’t go with any intention of writing about it. But there I saw the graves where a group of mummies (The Greenland Mummies) had been found in Qilakitsoq in 1975, and the setting—with the long, sloping, rocky hillocks and the huge grey sky overhead—stayed with me.

So my inspiration for the story were these mummies. Or, rather, the people who became the mummies. Because while they lived relatively recently—they’re thought to date to 1475—my characters are living long before the arrival of the Europeans in the Arctic.

As I started thinking about setting a story in this place, I found that I wanted to explore the edge of the development of human intelligence. So I had to go very far back. I also didn’t want to write the tragic story of the arrival of the Europeans in the Arctic. It’s a heart-breaking story and much has been written about it (though probably not enough), but I wanted to focus on a small group of ancient people.

By setting my story so long ago, and in a place so different from my own, I had to work to find the conflict and pathos among the characters. And I found it lay right where it lies among any people: in human relationships and the emotions that are common to us all. As with writing any fiction, the trick is to find the place where emotion sparks action, and action sparks emotion. Once I was going in the story, and once I found the characters, writing their interior worlds and their conflicts wasn’t different than in writing any other fiction.

Above all, I needed to find characters I would care about deeply, and I found them, mostly in Simut and Imiut. I was surprised how Imiut became a second protagonist.

Imiut is what we would call gender ambiguous, and yet living in a time eons ago. How did you come up with that?

Imiut is what we would call gender ambiguous, and yet living in a time eons ago. How did you come up with that?

I didn’t set out to write a story about gender identity at all; in fact, Imiut didn’t show up until I’d worked on many drafts over many years. But once s/he appeared in the kayak on the beach, I realized I wasn’t sure if this would be a man or a woman arriving, and then I realized that in fact, it was more interesting if I wasn’t sure—and if the other characters also weren’t sure.

Coming into play was also my knowledge of other First People who have in their communities “two-spirit” people, and that these people play an important role in the community. So while it may seem an anachronistic backbend, I believe it wasn’t unusual among ancient Inuit. And once I started writing Imiut, hir appearance worked in the story. S/he became an important, integrated part of the story.

Imiut’s ambiguous gender definitely made my reading experience more interesting because, to my mind at least, it opened up so many questions that animated the story. It was fascinating to see how the characters responded, how they managed their expectations about the role s/he would play in the group. And of course, as I read, I couldn’t help but reflect on contemporary struggles for gender equality. So it’s interesting to learn that s/he wasn’t originally part of the story you imagined.

I hope it leavens our current discourse about gender equality. Maybe knowing that there have always been gender-ambiguous people can make people see the absurdity about our conversations about who uses which restroom.

I learned a lot, in writing the book, not so much about the struggles of people who don’t neatly fit into gender roles, but about the freedom of letting go of an emphasis on gender. Gender is part of our culture and our life, but writing a character who is as fluid as Imiut involved a certain liberation of the mind.

However, even though gender-ambiguity fits neatly into the news of the day, it’s important that it wasn’t part of my original intention. I think there’s only so much planning a novelist can do before the book becomes boringly over-plotted. Sometimes you have to let something surprising happen, and see where it leads.

It’s always so interesting to hear how other’s creative processes work. Recently, I was asked which comes first for me: the character, a voice, or an image. For me, the image usually comes first, a scene of some kind—and it’s usually sort of hazy, like I’m looking through a dusty window. But I can see just enough to make me start to wonder. What comes first for you?

It depends on the work. With “The Sound in High Cold Places” it was the idea of the mummies, but once I started writing it, immediately I saw Simut: this very strong-willed girl who had an intelligence that for her time was prescient. I wanted to follow her around the tundra. But I know what you mean about peering through the dusty window; in fact, that’s an image I use with my students. I tell them to think of writing fiction as raising a shade on a window and looking down to see what’s happening in the fictional world.

That gets back to what I said about having Imiut. I thought the story needed something more—this was in a very late draft—and I remembered the quote, attributed to John Gardner, that in every story someone either goes on a trip or a stranger comes to town. Then I just looked onto that rocky beach in the Artic, to see who was coming, and it was Imiut.

I’m a huge fan of place and landscape and I was so impressed with the world you create in this novella. From the very first page, the world rises up around the reader in a way that’s completely captivating. How difficult was it to imagine?

You and I share that interest in setting, and a deep understanding of the importance of setting in fiction. It was in fact very difficult to imagine, but it was thrilling. I’d been to the Arctic just for a few weeks, so I had at least seen it. What impressed me most was the sheer enormity of it, how my perspective was seriously impaired just because the landscape was so much bigger than I’m used to. At one point, from the ice-breaker we were travelling on, I saw a polar bear on the shore; it was a tiny little white dot.

But more than writing about the landscape, and getting across the enormity of it, it was a great challenge to write about a people who wouldn’t refer to time the way we do. I couldn’t see saying “two days from now,” or “after breakfast,” so all the time markers that are so important in fiction had to be reinvented. And then there was the challenge of writing about people who have no wood to use, so they can’t be building a house or using stakes for a tent. They made everything from sea creatures and the sparse bit of foliage that grows there in summer.

Your research certainly paid off, because the details about everything from the terrain to food and hunting practices are so particular. And yet, they’re woven in seamlessly. I always love that in a story—that moment when I realize I’ve learned something new, but the author’s hand is still invisible.

Thanks. It took a lot to get that seamlessness. I can’t read historic fiction that keeps reminding the reader that we’re reading about a different time, and there were many times I felt I was awkwardly putting in details: “They sat down to a meal of seal meat in their igloo made of snow bricks.” I learned that it’s really tricky, making the setting of another time and place seem natural.

I never thought of myself as someone who writes historical fiction; with students who are working on historical fiction, I’ve thought I have no idea how to talk about it. Only after the book was published and I’d done some readings from it did it strike me that this is historical fiction. Very historical.

In an early draft, I decided that rather than making up words and names, I’d use contemporary Inuit language. Even though we have no way of knowing what language, precisely, people in the Arctic in 3,000 BC used, I felt this gave a feeling of veracity. And I used the name of the place where the Greenland Mummies were found: Qilokitsoq, The Place Where the Sky is Low. I just couldn’t abandon that place.

The language and imagery are so beautiful. Take this passage, for example, which is so lyrical:

Here at Qilokitsoq, The Place Where the Sky Is low, the end of the summer is both fast and slow, the sky still lit all day, but the air going colder each time the sun dips toward the earth, the sky lowering, foggy and white. The animals haven’t been plentiful, but there’s been enough food for Simut and her little group: the caribou have herded south, the ground shaking with their hooves, and there have been seals, and walrus, and always, fox and birds and eggs. Simut and her group have a cache of timiaak eggs, several racks of dried caribou. And from earlier in the summer, the last seal brought in by her own Oki, just before the ice softened beneath his feet, dropping him into the sea.

How important is language for you? I believe you used to be a poet, correct?

If I couldn’t use poetic language in fiction, I’d give up writing fiction altogether and make artisanal cupcakes. I’m very aware of the rhythm and rhyme in my fiction writing. Some stories seem to give themselves to it, and “The Sound In High Cold Places” is one. When I was starting to give readings from the book in the spring, I selected a passage in which Simut is re-telling the story of how her father died at sea, and as I practiced reading it aloud, I realized I had a single very long sentence, which really was a poem without line breaks. That was exciting to see—that I’d made a poem without realizing it.

That passage you quote starts off as a poem:

Here at Qilokitsoq

The Place where the Sky is Low

The end of summer is both fast and slow…

My first novel, Toward Amnesia (1996), is also very poetic, maybe because it was the first fiction I wrote after earning my MFA in poetry, and I didn’t really mean to write fiction, it just happened.

I get frustrated with writers who don’t pay attention to language. Not that every fiction writer has to be a poet, but we have to care about the words, how they play off one another, how they rhyme or don’t, how sentences can affect meaning just by their structure.

I was fortunate that my mother had studied poetry—with Theodore Rhoethke, at Bennington—and would recite poetry to us when we were kids. And not Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees,” though that, too, but she would recite Hopkins’ more disquieting poems, or Houseman, or Dickinson, or Plath. Maybe I should talk to my analyst about this. But I feel that this threaded poetry into my blood. And I still write and read poetry, in part to keep that part of myself alive.

I was fortunate that my mother had studied poetry—with Theodore Rhoethke, at Bennington—and would recite poetry to us when we were kids. And not Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees,” though that, too, but she would recite Hopkins’ more disquieting poems, or Houseman, or Dickinson, or Plath. Maybe I should talk to my analyst about this. But I feel that this threaded poetry into my blood. And I still write and read poetry, in part to keep that part of myself alive.

That poetry is in the other two novellas, though they seem to rely less on poetic elements. I was struck initially by how “In Case of Emergency Break Glass” and “Conversion” differed in tone and mood from “The Sound.” These stories feel less dreamy. All of a sudden we’re in the modern world. And yet you manage to pull forward some of the same thematic threads—issues of love and connection, the strong sense of place, questions about identity.

I’ve worried that the other two novellas may not seem to fit with “The Sound.” I wrote each at different times, in different places, and each is its own world. This is a funny thing about publishing: the publication comes so long after the book was written, and may not reflect the writing process.

I never thought of the stories as being of a piece; they all had to do with travel, but prior to submitting to Queen’s Ferry’s after I learned they were looking to publish a novella collection, I honestly didn’t see the other relationships among the three. But once it was published, I too could see those themes linking the three stories. Really, Simut isn’t that different from Elsie or Cassie: they’re all women finding out who they are. Simut is perhaps the one most free of illusion about herself. Cassie, in “In Case of Emergency,” is perhaps the one who is least aware of her own motivations, the most clouded by her desires.

You mentioned earlier that you wanted to write a story about a woman who was being gas-lighted. What drew you to that?

Maybe because I grew up in a very psychologically-oriented household, with a father who was a clinical psychologist and a mother with an interest in psychology, I’ve always been interested in a variety of personality disorders. Of course, reading and writing fiction requires some knowledge of the range of personalities, disorderd or not, and some understanding of the subconscious, and how it operates in us all.

The term “gas-lighting” is from a 1944 thriller, in which a husband convinces his wife she’s going mad. I think of it as anytime one person (or character) is manipulating another into believing things that are not true, usually about themselves. In this story, Ben convinces Cassie that she should stay with him, even though she herself (and the reader) can see that she should run in the opposite direction.

The term “gas-lighting” is from a 1944 thriller, in which a husband convinces his wife she’s going mad. I think of it as anytime one person (or character) is manipulating another into believing things that are not true, usually about themselves. In this story, Ben convinces Cassie that she should stay with him, even though she herself (and the reader) can see that she should run in the opposite direction.

I just find it fascinating that one person can control another through simple means of manipulation. We’ve all seen it, and maybe been on the receiving end, or we’ve manipulated someone, even in small ways. “Don’t you want to mow the lawn? Wouldn’t it feel great to be out there with the mower?” That kind of thing.

But for Cassie, she can’t afford to see how she’s being manipulated, and how this is leading her to lose her sense of herself.

A few days ago I was talking with a friend about this tendency I think women have to not want to believe what they see, even when they have all the evidence they need we often let our hearts override our better judgment.

Exactly. This is a feminine problem, I think, and it’s one I have myself, even though I’m aware of it in myself: I want to believe the reality I want to believe. If I like someone, I don’t want to see that they also have traits that make me uncomfortable. We also want to be nice, sometimes at the expense of our own knowledge of what’s true.

Was that an issue you were exploring with Cassie, because she seems to have all the information she needs to know she’s being played, and yet she hangs on.

Part of what I was doing with this story was writing my own version of a thriller. I wanted the reader to be yelling at Cassie, “Don’t do it! Run!” and then seeing her keep walking right into the quicksand. She does have the information she needs, but her need to believe she’s found her true love is greater than her ability to see what’s happening.

But I hope that readers have sympathy for her even while they become infuriated with her. I wanted the readers also to see that it’s easy to become infuriated with Cassie, and to let Ben off the hook, in a kind of blaming the victim.

This story dealt with a different facet of the whole identity question. In “The Sound in High Cold Places” you were exploring questions of fluidity and how identity rates to one’s community. Here the question of identity seemed to center around questions of invention and reinvention: how we lose ourselves and have to rediscover who we are, or in Cassie’s case, she discovers who she is for the first time.

Exactly. In all the stories, the reader is seeing the characters change—at least, the protagonists. All the protagonists go through some kind of metamorphosis.

I think the reinvention of Imiut in “The Sound in High Cold Places” isn’t that different from Cassie’s reinvention of herself. We never hear much about Imiut’s past, s/he just shows up on the shore in a kayak, broken and alone. At some point, I think Imiut must have reinvented hirself, and that’s another story I’m currently exploring, as I’m considering expanding that story into a novel.

Cassie has to go through the fire in order to experience her transformation, as does Elsie in “Conversion.”

I absolutely loved the final novella, “Conversion.” You set us down in another foreign landscape which was so subtly presented. The story brought to mind Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” where the tension between the characters builds against this beautiful landscape. What inspired this story?

Okay, now that my work has been likened to Hemingway, I can die happy. But not just yet. Yes, “Conversion” calls on “Hills Like White Elephants” in atmosphere and subtlety. I also called on, and re-read, The Plague, and Hemingway’s last novel, a peculiar, disquieting story called Garden of Eden. I wanted to capture that subtle, constant rise in tension, and, as you say, against a beautiful landscape.

“Conversion” is the one story in the collection that’s truly autobiographical. The inspiration was in fact a trip I took to France with my partner, not long after we’d gotten together, to see his bullying brother. I actually started planning to write “Conversion” as it was happening, as a way of getting through the experience. I’ve done this with other works of fiction, where I’ve been in some bad situation and started thinking of it as a story in order to get through it.

The tension in that house was so thick, and there was a constant feeling of impending disaster.

The tension in this story is submerged for so long, and then it explodes.

That’s just what I wanted. Unlike the title story, where we see right away that Cassie’s in trouble, in “Conversion” I wanted everything to seem idyllic at first, and only gradually for the reader to feel that tension coming to the surface. It took a lot of re-writing to get that tension to build slowly, and then I must have re-written the final scenes a hundred times in order to get the explosion to feel right.

The trick is that you have to have the tension on a low burner, without too suddenly popping into flame. There’s a delicate balance point at which the reader will feel that satisfaction of having seen what was coming but also be surprised. That feeling comes from a carefully-calibrated rise in tension. It’s easy to ruin that rise by coming in too soon with the blow-up, or not having the blow-up have a volume that matches the build-up.

For a long time, through several drafts of the story, I had more than one dinner with difficult, very tense, conversations, but as I worked on the story, I could see that just kept the reader in a soupy limbo of tension, without anything moving forward.

I also thought it was so interesting to watch the family dynamics unfold. It called up all kinds of questions about loyalty and identity; what we do to escape our past; how we reinvent ourselves, the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Can you share what was going through your mind as you created these characters? Because all four of them surprised or infuriated or charmed me in some way—well, maybe not Royal…

At the time, I couldn’t see the flaws in the character based on myself or Nick—it felt like we were simply being bullied. But later, as I wrote the story with some distance, I could see the parts that Nick and Elsie were playing, and I could see they were not faultless.

The story that Elsie tells herself is that she’s in this great relationship, and she’s going to have this great experience in France. But she learns it isn’t that simple, and that she has more responsibility than she’d thought in making the experience what she wants. But she also has to be herself more genuinely in order to have the life she wants—and that’s something that isn’t easy for me, or, I think, for most of us.

There’s a real similarity between Elsie and Cassie (even their names are similar) that I wanted once the collection started coming together. As you said earlier, often women see what we want to see, not what’s right before us. Cassie can’t see what’s obvious to the reader, but Elsie can’t see what may be less obvious, that Nick is not able to stand up to his brother in her defense, and that she could wrest control and make the visit better—though of course still imperfect—if she wanted to.

All these characters are trapped in themselves, in who they are, which is a function of how their selves were created in childhood. Again, back to my own experience being raised by psychologists—I think that gave me this insight into how we work, even though I still have my own blind spots about how I work. It’s really saved me, so often, to be able to make up a story about something, and to imagine my way into the interior world of my characters.

Which is really the power and the beauty of fiction isn’t it? To help us make sense of our lives and to impose order to what is otherwise a crazy, chaotic world.