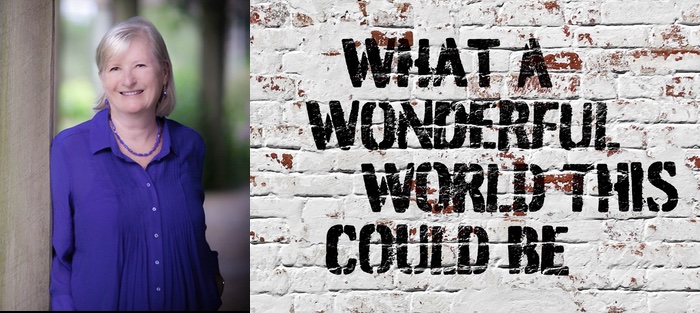

From memoirs to academic histories, loads of books have been written about the 1960s and early 1970s. But Lee Zacharias’s What a Wonderful World This Could Be (Madville Publishing) not only reflects on these heady decades, but also extends into the early 1980s, when a small number of activists—some of whom had bombed military installations—began to resurface from life underground to face the criminal charges that were pending against them.

As the novel unfolds, near-constant demonstrations for civil rights and an end to US involvement in Vietnam are taking place. Feminists and LGBT activists are beginning to demand recognition and respect, and communal living is burgeoning. As a documentary photographer, Alex, the novel’s protagonist, uses her camera to capture the excitement. At the same time, hers is the perspective of an insider-outsider and she remains somewhat aloof from the action—at least initially. This changes when she becomes romantically entangled with Ted Neal, a charismatic leader of the New Left. Within months, her life is completely upended. Other relationships, with women friends as well as with Steve Kendrick, a mentor who later becomes her lover, are also part of an intricate, satisfying, mix.

Interview:

Eleanor J. Bader: Did you participate in any of the social movements of the 1960s and 70s?

Lee Zacharias: I graduated college in 1966 and the first thing I did was get married. I worked in a research center while my husband attended graduate school at Indiana University in Bloomington. Most of the political activity on campus took place at Dunn Meadow, which was right around the corner from my job, so on my lunch hour I’d stroll over. During these years, women had to wear skirts to work so I stood out from the students. I felt like I watched the story of my generation on the TV news rather than participating. Even though I had differences with the most radical parts of the movement, I wanted to belong.

Finally, after my husband and I moved to Richmond, Virginia, in 1970, I was able to trade my pantyhose for bell bottoms. I went to the last large antiwar demonstration in Washington, DC in 1971.

How did you develop the idea for What a Wonderful World?

How did you develop the idea for What a Wonderful World?

When my first novel went to press in 1980, my editor suggested I write a political book, though that was not my thing. But one night I was at his house for dinner and I picked up a newspaper. Cathy Wilkerson—a member of the Weather Underground whose family townhouse in New York City had been accidently destroyed when a bomb the group was making exploded—had just turned herself in after ten years on the lam. I started thinking about her family and friends. I also wondered what it would be like to have your partner vanish, disappearing underground without a trace. Did those who went into hiding think about those they left behind? These questions became the seeds for What a Wonderful World.

The novel integrates real people from the New Left with fictional characters. How did you decide who to include?

The real characters are there for verisimilitude. I did not want to make everything up, but I did ask myself if I wanted to write about real people. I changed the name of the university and the town, but the town is modeled on Bloomington and the university is modeled on Indiana University.

Did you do a lot of research?

I actually thought I was taking a shortcut with Alex because, like her, I am a photographer, but I still read everything I could get my hands on—memoirs, journalistic accounts, the so-called New Journalism of the 1970s and 80s. Norman Mailer’s Armies of the Night was particularly instructive. I also read Jane Alpert’s Growing up Underground; Cathy Wilkerson’s Flying Close to the Sun; Bill Ayer’s Fugitive Days; and John Castellucci’s The Big Dance, among many others.

In addition, I researched the March from Selma to Montgomery, the voter registration drives in the south, and the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. I had to write scenes about these events and I wanted them to be realistic, resonant. I visited Selma and retraced the route of the March, but I opted not to interview people who’d been part of the Weather Underground or Students for a Democratic Society because I knew that I would not necessarily be putting the same spin on the era as they would.

How long did it take you to write the novel?

Too long! I started it in 1981. I was teaching at Princeton at the time and then moved to Greensboro, North Carolina. I taught at the University of North Carolina for thirty-three years, teaching English and creative writing, directing a graduate program, and editing The Greensboro Review.

By then I’d gotten married for a second time and had a child, but I finally sent a draft of What a Wonderful World to my then-agent in 1990. Houghton-Mifflin had an option on it, but my editor left the job before I’d put the finishing touches on the manuscript. The editor who replaced her was not interested in the book.

Part of the problem was that the 1990s was a time of great upheaval in publishing. An editor would express interest in the book but they would be fired or resign before I signed a contract. This happened four or five times and my agent eventually told me to throw the book away and write something else.

After this, I sent the novel out a few times myself, but by then there were so many books about the 1960s that it was like trying to sell last year’s pet rock. I put the manuscript on a shelf where it sat for several years. Sometime later, I sent another book I’d written to a new agent and she asked me if I had anything else, so I sent her What a Wonderful World. She liked it but suggested some revisions and restructuring. She then moved to California and seemed to lose interest. As a result, we parted company.

Years later, a friend who was working on an anthology for Madville Publishing suggested that I send the manuscript to them. I did and it was accepted. The upshot is that it took nine years to write and thirty years to market the novel.

You don’t say much about living underground.

The book is told from Alex’s point of view and she is the person who had to deal with her partner’s disappearance. Her character also offers readers a different way of being politically active since she is not like the people who went underground. Although she took political risks at times, she wanted to hold onto her personal and artistic freedom.

As for life underground, my feeling was that if readers don’t know anything about this, maybe the novel will provoke them to do some research. I also would have had to step out of character to explain what this meant.

Steve Kendrick is a complicated man, an ambitious photographer who seems oblivious to politics and social justice campaigns.

Steve was absorbed in his art in the early 1960s. At the beginning of the story, he is not a good guy; but he genuinely fell in love with Alex even though he knew he should not act on his feelings. Once Alex leaves him, he grows and understands that getting involved with her is wrong, and I wanted to redeem him. After Ted vanishes, he offers Alex unconditional support and does not touch her until she gives him an opening. He is not oblivious to politics, although he is not an activist. Particularly as time goes on, he is very aware of what the US government is up to and in 1982 voices his disapproval for its sanctioning of the violence in El Salvador. He is originally from Canada, and because he is not active during the time Alex is with Ted the reader does not see him change politically, but he would have become a citizen; he votes. And when he takes the teenaged Alex to Canada to meet his parents, they voice their disapproval of American foreign policy. He is a foil to the most politically active characters in that he does not become a prisoner of a rigid ideology, but he certainly has a political conscience and political consciousness.

Do you think Alex’s childhood influenced the way she experienced Ted’s disappearance? After all, her mother all but abandoned her as a child. Alex’s mom essentially used her daughter as a prop and was incredibly negligent when she was growing up.

It took me a while to figure her out. I knew that I wanted Alex to be neglected, but I had a hard time coming up with the motivation for her mother’s cavalier attitude. I ultimately realized that her mom could have considered having a back-alley abortion, but because she was in love with Alex’s father, she thought—hoped—that having his baby would give her leverage. When it didn’t, she ignored her daughter. Maybe when Alex was a baby, she had to be a more attentive parent, but we know that by the time Alex was old enough to feed herself, her mother could not be bothered with the details of her child’s life. This left Alex with a lot of repressed anger. She is sometimes impulsive and self-destructive. A lot of this is gendered, but Alex’s background made her unlikely to express her rage.

For example, two years after Ted disappeared, Alex could have gone to a lawyer and gotten a divorce on grounds of desertion. She could have moved on but she remained loyal to Ted; of course, her feelings were further compounded by her repressed fury. She is really traumatized by Ted’s move underground. Ted, however, was not immobilized. He was not stuck but was instead living a new life underground. His decision to leave Alex was based on the fact that the FBI would have forced him to come forward and testify against his friends. He could have refused and faced the consequences, but he ran. Some may see this as cowardly.

It also gives the novel nuance—people are complex.

I’m a photographer as well as a writer. As a photographer, I’m always aware of framing, paying attention to what I choose to include in a particular picture. This also plays out in writing because I’m framing what interests me. Alex’s story is the one that interested me, but as a writer I had to understand Ted’s motivation even though I didn’t write it.