Most writers are encouraged by late-in-life publication stories. We’re heartened by the fact that Carol Shields was fifty-eight when she published her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Stone Diaries; that Frank McCourt was sixty-four when Angela’s Ashes came out; and that Belva Plain published her first novel when she was a sixty-three-year-old widow. Even better, Plain then proceeded to publish twenty-one novels that made the New York Times bestseller list!

These and many other examples reveal the wonderful truth that we can write at any age. Unlike football players or underwear models, there’s no built-in expiration date for writers. And while marriage, motherhood, and moves may take up a great deal of time in our life trajectory, they also add to our wisdom.

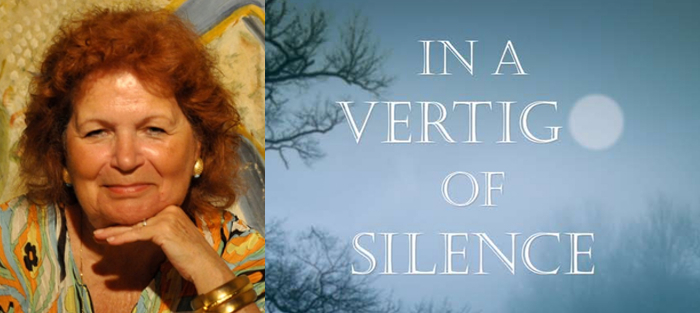

Miriam Polli has turned her own fascinating life journey to good use, making the recent publication of her first novel, In a Vertigo of Silence (Serving House Books), cause for celebration. The novel spans four decades from the 1920s to 1960s and shines a warm light on family secrets that have haunted several generations of Polish women. Mental illness, alcoholism, adultery—and the many things we do not tell those closest to us—are the dangerous threads woven through these women’s lives.

I’m personally delighted because Miriam and I were members of the same NYC-based writing group for several years, and I know how hard she’s worked to see this important project come to fruition. I was happy when Miriam shared some of the experiences on her non-traditional path to publication with me.

Interview:

Donna Baier Stein: I know first-hand that it can be a real challenge to combine the responsibilities of family with writing. Can you talk a little about your own experiences with this issue?

Miriam Polli: My love for writing has always been there, but my family, well, they’ve always come first. I had my first daughter when I was eighteen, my middle daughter at twenty-eight years old, and my youngest, a few months shy of forty. So I was mothering for almost forty years. When my youngest went off to college I suffered greatly with that damn “empty nest” syndrome. It’s quite real.

Through those years I had also lost two of my sisters. Sisters I spoke to on a daily basis. I tried working but felt too depressed, so I traveled a lot, visiting my daughters when I could, jotting down notes on airplanes, underlining articles of importance about writing, tearing outstanding author interviews out of magazines. I was reading about writing all the time and above all searching for the novel that would blow me away.

So when did you first know you might want to be a writer?

I was in the fourth grade and my teacher, Mrs. Staver, who I still think of dearly, caught me chewing bubble gum. She said I had to write a letter of apology to her. I did, and the last line I wrote was that I could not promise her it would never happen again, because I was a human being, after all. And human beings make mistakes. [Laughter.]

She gave me an A+ and told me I was going to be a writer.

Then, in the 5th grade, I wrote a play called “The Magic Hat.” It won a talent show. So I’ve always wanted to be a writer—since childhood. It was an outlet, and, I think, a way to hold my own identity amidst the chaos of my older siblings.

So once you knew you had this urge to write, what were the first steps you took to follow that passion?

When I was eighteen years old, before I finished high school, I mustered up the courage to attend a Hayes B. Jacobs class in Creative Writing at the New School of Social Research. I wrote my first short story in his class and felt very proud of it, because it was a real story. He red-penciled the entire piece because I failed to indent the paragraphs. He also pointed out a number of small grammatical errors, mostly run-on sentences, which I still have to watch.

He held it up to the class as a poor example of writing. He never once mentioned the content. I had poured my heart out in that story, and it really crushed me.

I’m sure. So what did you do after that class?

Twenty years went by before I picked up another pencil to write. I did nothing but read, read, and read—about writing and all the short stories and poetry I had the time for. After all, I was then working and supporting my two daughters as a single parent.

One night I could no longer hold back—it was as though I was going to explode if I didn’t write. So I sat down once the kids were asleep and wrote a short story. Actually, I wrote two in a week’s time. I had read that John Gardner—

Truly one of my favorite authors!

—was going to give a lecture at Hofstra University, and I was very excited about going. After reading his book The Art Of Fiction, I knew he had some wonderful things to say about writing. Only a small group of people attended the lecture, so I took the opportunity and approached him. I had been reading so many short stories in Redbook and Family Circle at the time, because, after all, they paid, and I really needed the money. But I was also reading Harold Brodkey in the New Yorker and loving him.

So I asked Gardner how a writer could compromise their “art” and have commercial success at the same time. Boy, was I bold. Such literary pretension!

He was very gracious, though, and asked me to send him a story or two. Of course, I ran home and retyped the stories and sent them to him the next day. (I was afraid he’d forget he’d told me to send them.) Six months later, only two months before he was killed in the motorcycle accident, I received a letter from him in his own script. He said some wonderful things about my writing; he called my language brilliant, and that was all I needed. So, yes, John Gardner, without his knowing was probably my greatest mentor.

He was very gracious, though, and asked me to send him a story or two. Of course, I ran home and retyped the stories and sent them to him the next day. (I was afraid he’d forget he’d told me to send them.) Six months later, only two months before he was killed in the motorcycle accident, I received a letter from him in his own script. He said some wonderful things about my writing; he called my language brilliant, and that was all I needed. So, yes, John Gardner, without his knowing was probably my greatest mentor.

A few years later, I attended a workshop at Hofstra University, where Helen Morrissey Rizzuto, a wonderful, caring teacher of writing, encouraged me. She is now a lifelong friend. And through the years I’ve attended a number of conferences. I presently live in Key West, and I’ve probably participated in twenty of the Key West Literary Seminars. One of their earliest authors, James Dickey, gave a really exciting talk many years ago on believing in your own work. I was sitting in the front row, and it was as if he was speaking only to me. He was so real, so present, so full of life. A wonderful “bear” of a man, with a deep southern drawl. He talked mostly of a writer’s self-confidence, of following your voice. “Don’t shy from it,” he said. “It’s your strongest ally.” He was rough, tough, and when he said, “Don’t let others influence you with their opinions,” I felt myself sort of pulling together. “Your own opinion of your work will fluctuate wildly,” he said, “but don’t be fooled. It’s there in your gut.” Checking my notes again after all these years, I see I’d underlined “wildly” many times, because I felt his essence in that very word—it lingered in my ear. He also said that poetry was at the center of who he was, and if he lost that—he’d lose everything. He had a very black and white philosophy, and it was just what I craved at that time.

I also remember Gordon Lish at the Southampton Writer’s Conference walking around in his Safari getup—boots, hat, and all. And he said, “You are the God of the page.” I really liked that.

Hearing these writers speak gives you a sense of confidence. I loved just being exposed to other writers. I had been reading so much about writing through the years that lots of what I heard at these conferences was repetitive, but I’m certain I absorbed so much that it is really difficult to articulate now.

Writers in general have always inspired me. Over my desk is the famous Babel quote: “No iron can pierce the human heart as a period in just the right place.” And another saying over my desk, an incredible quote, is from the artist Robert Henri. In his book The Art Spirit, he says: “There are moments in our lives, there are moments in a day, when we seem to see beyond the usual—such are the moments of our greatest happiness. Such are the moments of our greatest wisdom.” For me, I guess I’ve always strived for these moments.

So how does it feel to now have your book finally out in the world? Were there times in your writing process that you felt you’d never see your novel published?

Of course! There were many, many days that I felt I was wasting my time. So, yes, now that the book is here, naturally I’m thrilled. Thrilled, and at the same time I hardly believe I was the one who struggled to put it all together. To make a complete, whole story. It’s about the validation, you know. All those years with the characters, the words, thinking your characters are too slight, not interesting enough. Worried that your so-called plot doesn’t have enough plot. Then you sit back one day and think, “Who really will care about this? It’s just another story that’s been told so many times, just in different ways.” Yet there is that illogical reasoning, or rather lack thereof, that makes you continue.

But something obviously kept you going. And the story kept pushing to be told. Can you tell me a little about the story’s genesis?

This novel grew out of a short story. I was writing poems and short stories on and off for years. Short stories were my first love. I was in a small writer’s group, three or four of us, and after reading the story, which I believe is now a slight variation of Chapter 5, the consensus in the group was that this was just the beginning…that I had a longer story to tell, enough for a novel. Oddly enough I happened to agree on a sensory level.

I say “oddly enough” because writing longer pieces was something I had never planned to do. I always said, “I don’t love writing, but I love having written.”

Subconsciously, I think I chose the short story form because the thought of a novel seemed so stressful and impossible—all those pages.

I sent that first story out a few times and got some glowing rejections, but all along I kept thinking about the protagonist. I guess you could say she was haunting me. Haunting as only our characters can do. And after a while you have no choice but to give into the ghosts they send to you.

Did you know at the beginning that you wanted to tell the story from different points of view?

No, not really. Since I felt I was a short story writer I thought I’d approach each chapter as though it were a story. It seemed the only sane way I could handle it. At one point my husband was building a fireplace in our kitchen on Long Island, and as I watched him, I kept telling myself, it’s the same as a bricklayer, brick on top of brick until the whole wall is done. Eventually, the main character, Emily, took over. Questions began to rise: “Why is she so troubled? Who is her mother, her grandmother, and who else was in her family? Where was her father?” So I began to write each character’s chapter. Trying to flush them out, not really knowing if I’d keep their voices. Reworking from first-person to third-person point of view, and in some cases present tense until I felt I knew who that person was.

I love that image of laying brick on top of brick until a wall is complete. That’s so true about the writing process. And, of course, because your novel takes place in different historical time periods, part of that process must have involved research.

I’m guessing that at least some of what is in your book comes from memory and/or from your own family stories, but did you augment that with research for the chapters that aren’t set in contemporary times?

The only real research I did was for the grandmother’s chapters. I read quite a bit about coal mining in Pennsylvania, and then my own mother had come through Ellis Island from Sicily as a young girl, and I remembered or rather imagined some of her stories and did some research on immigrants entering Ellis Island. My first marriage, when I was much too young, was to a Polish boy. His Grandmother, who spoke no real English, and other members of his small family, left a strong impression on me.

Most of the book is sheer imagination, with the exception of emotional content. Life serves us up many tragedies: death, pain, loss, love, jealousy, anger. So much so, that we cannot leave this earth without feeling most of these emotions.

Although my parents were both born in Italy and I was raised with five siblings in a crowded Brooklyn flat, one could even say I lived a life close to a tumultuous Italian opera. [Laughter.]

There were so many emotions!

Perhaps, I was trying to disguise my own family by making this novel about a Polish family. Not much of a cover, huh?

Finally, can you describe your revision process?

Wow, revision is always a problem for me. It takes me years to write one book, and in this case, almost—if not more than—twenty years, because of the way I write. You’ve read or read writing instructors who say you should write the first draft completely. I find this impossible. When I write, I write one line at a time. I do not go on to the next line until I feel I have the first line the way I want it to be. And the next day, I start from the first line again until I do it over and over and find I no longer need to revise that section.

Another reason I find revision difficult is because I do not write with a story outline. I have a vague emotional sense of where I want to go with the character, and I sort of wait for the character to lead me. I truly wish I could put down a complete first draft—it sounds great. The book I’m working on now, even though I know the end because it’s historical fiction, I find I still must work this way. In the end, my creative process is painfully slow, while revision has always been scary for me. I know some writers think of it as being the best part of writing. I’m always afraid with too much revision I’ll end up not having the impact, the original sense of where I was headed. There is a certain balance of characters and plot that is so vulnerable. Yet at its completion of my first novel, hence its publication, I see that revision really does pay off, and perhaps at this moment, am less afraid of it.