Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

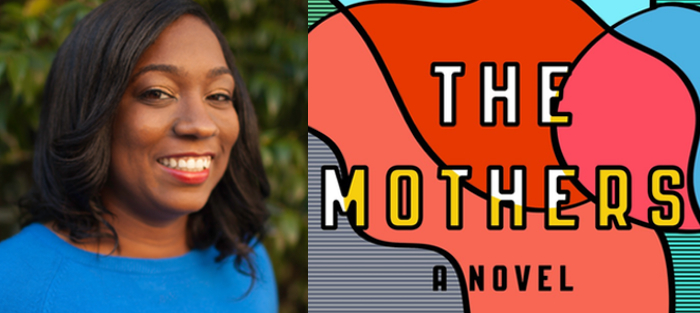

In today’s feature, Chris McCormick talks with Brit Bennett about her debut novel, The Mothers. This interview was originally published on October 12, 2016.

Whatever alchemy it is that allows you to recognize the strangers who will become your people, I felt it immediately with Brit Bennett. We met during the “Welcome Weekend” for our MFA program in Ann Arbor, when we were both young transplants from California, hoping to write great books and in search of a decent coffee shop. Even early on, our conversations seemed able to switch modes without grinding gears, so that over the same glass (or four) of wine, we could compare Toni Morrison’s novels to the albums of Jay Z, plan an impromptu trip to Las Vegas, and discuss endlessly the obstacles we’d faced that morning in our work. We were curious about style and structure, and mostly about character. What moves a person to return home after clawing for so long to leave? Why do people never see it coming that their bodies will betray them? What makes a friendship hum?

In conversation and on the page, Brit Bennett is a thinker who follows her curiosities to more complicated questions, never settling for the comfort of conclusions. Her essays—for Jezebel, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The New Republic, to mention a few—seem to me to be the antitoxin we need against an onslaught of “hot-takes” and “think pieces” that ask nothing and contribute less. Bennett is a writer who understands that “and” is more interesting than “or,” and more powerful, too. Readers and givers of accolades—including the National Book Foundation, which recently named Bennett one of their prestigious “5 Under 35”—have flocked to her work, craving the complexity of thought and heart and humor and pain to be found there.

Her debut novel, The Mothers—which tells the story of a black church community in California and the secretive, grieving young woman who leaves it—is out this week from Riverhead to incredible anticipation. Recently, over email, I had the chance to continue once again my ongoing conversation with its author. We talked about the book, about the writing life, and about how badly I—and the wine industry in Ann Arbor—miss her.

Interview:

Chris McCormick: It’s risky to lead with the most important question, but here it goes: will you please move back to Ann Arbor?

Brit Bennett: I miss you guys too, but the cold! Okay, in a dystopian future where climate change has transformed Michigan into a tropical rainforest…maybe.

I hate that I’m now rooting for climate change.

Okay, let’s get to your wonderful book, The Mothers. At one point early in the novel, the group of church mothers who narrate and annotate the story of Nadia, Luke, and Aubrey define the kind of prayer they practice:

More than just a notion, taking up the burdens of someone else, often someone you don’t know. You close your eyes and listen to a request. Then you have to slip inside their body…If you don’t become them, even for a second, a prayer is nothing but words.

This sounds a lot like the job of a fiction writer. Do you consider the church mothers writers of a kind? How do you understand their role in the novel?

You told me once—which I have since stolen, thank you very much—that the church mothers function as a type of social media within the novel. They observe and comment and transmit information within and about the community. But I also think of them as writers, in a way. Culturally, we often trivialize gossip, but gossip can be a powerful form of storytelling. Gossip allows us to construct narratives around each other, narratives that often have big consequences.

At the same time, Nadia tends to believe that “you could never truly know another person.” Can you talk about the distinction in your process of creating characters, if there is one, between empathizing with a character and truly knowing her? How well do you feel you know these people you’ve invented? Did you have moments that felt epiphanic about any of the characters, or was it a gradual process of understanding them?

It’s tough because these characters don’t exist apart from me creating them, so if I don’t know them, then who does? That being said, and at the risk of sounding precious, when you work on a book for years, it sometimes does begin to feel like you are slowly learning things about people who exist. I think characters resist being known in the way real people do. When I start to construct a character, I never begin with their deep dark secrets or biggest fears or hidden shame. I usually start with the surface details—physical features, occupation, interests—and over time, I learn the things the character secretly wants or hates or tries to hide.

It’s tough because these characters don’t exist apart from me creating them, so if I don’t know them, then who does? That being said, and at the risk of sounding precious, when you work on a book for years, it sometimes does begin to feel like you are slowly learning things about people who exist. I think characters resist being known in the way real people do. When I start to construct a character, I never begin with their deep dark secrets or biggest fears or hidden shame. I usually start with the surface details—physical features, occupation, interests—and over time, I learn the things the character secretly wants or hates or tries to hide.

One of the best writing exercises I did while writing this book is just to write pages of backstory about certain characters, 90% of which never made it into the novel. But it allowed me to get to know a character deeply in a very low-stakes way. I took the pressure off myself by agreeing it wouldn’t go in the actual book and I started writing about, say, Luke’s mother. Then I would stumble upon an interesting detail about her, which would often bleed its way back into the book.

Yeah, and the reader definitely gets a sense of that depth of character off the page. Your willingness to do that invisible work has to have been one of the fundamental reasons you’ve made it as a writer, right?

I think I had to learn that writing is more than your word count. I had plenty of those frustrating days where you write all morning just to realize it wasn’t working and I needed to delete everything. At first, those felt like wasted days, but I had to learn to realize that invisible work is real work. Learning what story you don’t want to tell is as important as learning which one you want to tell. You have to teach yourself how to tell the story and a lot of that teaching happened in these pages of writing that nobody but me will ever see.

One thing I love about the book is that—for all its concerns with love and faith— we’re always reminded of the importance of the body. Can you talk a little about the way the body confines and sometimes redeems these characters? There’s a gorgeous scene during Halloween where all these people are dressed as angels, making literal this conflation of the heavenly and the earthly. Can you talk, too, about writing that scene in particular—were those ideas in your head as you wrote it, or were you surprised to see one of the book’s themes materialize so perfectly?

One of my favorite quotes about Christianity is from Michael Eric Dyson, who puzzles over the irony of the church warring with the body. The whole purpose of Christianity is the incarnation, he says, the idea that God takes on flesh, yet the church constantly fights with the very materiality of the body and its needs and its desires. I think about this often—although probably not consciously as I was writing—and I think a lot of the conflicts in the book arise from this tension with the body. Nadia’s unwanted pregnancy, of course, but also Luke’s disappointment with his career-ending injury, or even Aubrey’s difficulty reconciling with her body after a childhood of abuse. I like your reading of that Halloween scene, although that also wasn’t something I wrote consciously. I just liked the idea of this church Halloween party where you could dress as a biblical figure but not a negative one. I think the desire to look to the heavens and suppress anything dark or ugly or uncomfortable is a theme that runs throughout the book.

Speaking of uncomfortable: Rebecca Scherm—novelist, mutual friend, and interview-sadist—once asked me what my deceased character might have thought, had he lived, of his childhood friend’s adult life. It was a difficult and strangely painful question to answer. So let me pass that onto you: what do you think Nadia’s mother might have made of Nadia’s life, including her choice at the beginning of the book?

Speaking of uncomfortable: Rebecca Scherm—novelist, mutual friend, and interview-sadist—once asked me what my deceased character might have thought, had he lived, of his childhood friend’s adult life. It was a difficult and strangely painful question to answer. So let me pass that onto you: what do you think Nadia’s mother might have made of Nadia’s life, including her choice at the beginning of the book?

Well, thanks, Rebecca, that question just punched me right in the gut.

I think her mother would have supported her decision to end the pregnancy but regretted the pain it causes her. I think ultimately her mother would have been proud of her life. Nadia explores the world. She goes where she wants. She follows her desires. She makes mistakes but they are her mistakes.

I remember you once read a portion of an earlier draft from Nadia’s mother’s point of view, and people in the audience were legitimately weepy and shook. I was like, “You guys, this isn’t even in the book!” You know it’s a great novel when the B-sides are making people cry.

Ha! Oh man, one of those sections I had to cut during edits. Maybe I should release The Mothers Deluxe Edition with some bonus, unreleased sections.

I just heard a chorus of “YES, PLEASE” ring through the land. Hey—what do you make of the comparisons between your novel and the novels of Toni Morrison, especially Sula and Beloved? A compliment, to be sure, but maybe a lazy one? Are there other novels you had in mind while writing The Mothers that you wish people would bring up more in conversation?

Ha! A compliment and a lazy one. On one hand, Toni Morrison is my favorite writer of all time, so it’s an unbelievable honor to be mentioned in conversation with her. On the other hand, 90% of black woman writers are probably compared to her at one point or another. I think my novel has some similarities with James Baldwin’s Go Tell it on the Mountain, though—both books about ambivalent characters caught in repressive Black church communities. I loved how that book slowly peels back layers of the older characters and slowly humanizes them, which is something I tried to do.

I thought about Steinbeck, too. Something about the way relationships emerge out of these makeshift communities.

Right, I think makeshift community is a pretty accurate way to describe a military town. People are always coming and going.

Military, right, and maybe California en masse. Some of the most haunting images from the book occur at the beach, at the shoreline. Do you think your proximity to the ocean growing up affected your fiction in a fundamental way? Do you think of yourself as a Californian writer, and what do you think that means?

California is such a vast and diverse state, so I don’t know how I would define a “California writer” or a “California literary tradition.” But I’ve spent most of my life living in California, and I didn’t start to think about what that meant until I left for grad school in Michigan. I think aspects of my writing that reflect California—aside from the setting—might be the racial diversity, the many characters who are geographical transplants, and a climate that is both paradisal yet often harsh.

The reason you left California was to meet me in graduate school in Michigan, right after graduating from some university with a tree as its mascot. Some people urge young writers to steer clear of an MFA program for at least a year or two after college, but you came straight away. Why do you think you were so successful—in finishing the book, not just publishing it—and what advice would you give to young writers who think they’re ready straight out the gate? Is there some kind of maturity checklist you’d suggest?

I had several people warn me against going straight to an MFA program, but I ignored this mostly because I was graduating with an English degree and no job prospects so I figured, why not just apply. I think for anyone to succeed in an MFA program, you need to be confident in your own voice and vision, yet humble enough to learn how to improve; you need to be disciplined and self-motivated; and you need to have an interesting voice and something interesting to say with it. I struggled at first, because it’s difficult to be confident when it seems that everyone in workshop has read more and knows more about life. I’d never been given so much unstructured time to write before, so I oscillated between writing and panicking that I wasn’t writing enough. And I often worried that I hadn’t lived long enough to have anything worth writing about. Ultimately, I had to learn to trust myself and to trust this book. I learned how to be more disciplined and I surrounded myself with people who challenged me to be better. I think a young writer who is ready to go straight to an MFA program needs to be confident enough that the criticism won’t crush her but eager to listen to it anyway, and disciplined enough to handle the pressures of being alone with the page. If not, then maybe wait a few years.

Having worked on the book for many years, were there times when you threw your hands up and wanted to quit? How did you get through those times, if so? And if not, how did you keep the faith that your vision would shine through the many, many drafts?

I’ve honestly been wondering this question myself recently, because this book was so bad for so long! I started writing it when I was a teenager, so I knew nothing about writing fiction and I knew little about life. Not just that, but while drafting it, I dabbled with other ideas here and there, but for some reason, I always returned to this book. Something about this story and these characters refused to let me go. I was also fortunate enough to have a couple of mentors along the way who read these early drafts and encouraged me to keep writing. I feel very lucky to have met people who were so generous to me when they had no reason to be. I think it all comes down to, as you said, faith. Deep down, I always believed that this book could be good. I wanted it to be as good as it was in my head and I wanted to be the writer who could tell a story about these characters who had captivated me.

Despite writing and publishing some great short stories, you’ve always told me you’re more naturally a novelist. What distinguishes the two from one another, do you think, and will you write more stories in the future?

I don’t know! I think short stories are a million times harder to write than novels. I always struggled to write stories because I wanted the world to constantly expand. I wanted to know everything about a minor character. I hated having to be concise. And I think there’s something psychologically that comforts me about writing a novel, the idea of returning to the same project and the same characters and the same world every day. I would finish a story and feel completely unmoored like, well, crap, what do I do next? I could see myself perhaps writing interconnected stories one day, which might speak to my novelistic tendencies but also challenge me to work within the story form. That being said, I have deep respect for the great story writers among us and out of that respect, I’ll probably stay in my lane. Which is not stories.

Your lane is wide, Brit. It seems to include essays, too—along with your novel, they’ve helped make you a star in the literary world. You’ve been selected as one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35, and—clearly more importantly—you’ve graced the pages of Vogue. I know you well enough to know that your head will remain in the work, but the wild success of your debut has to have some affect on the next novel, doesn’t it?

Ha! Okay, this is a very generous reading of my life. Well, the excitement surrounding the book is completely surprising and overwhelming and encouraging. But I try not to focus on any of it when I write. The hype happens outside of you. You can’t create it, you can’t stop it, and you can’t make it last. I’m grateful that readers have responded so warmly to The Mothers, but I’m always looking to challenge myself in new ways. So the new book will tackle a new geographical setting, a different time period, and a larger cast of characters. The Mothers is tightly-written, so I want the new book to be a bit more expansive.