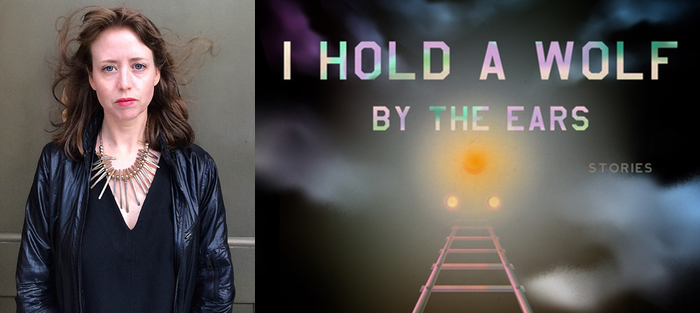

I was on an overnight flight to Moscow, a month before the pandemic shutdown, when I opened I Hold a Wolf by the Ears (FSG) for the first time. In the restless dark, by passenger light, I read the first story, “Last Night,” cursed under my breath, and immediately closed the book. For much of the remainder of the flight, I thought about that story and the delirious perfection of its architecture.

A good short story collection is like a good collection of poems, rich enough that you want to consume it slowly and linger between the covers for as long as you can. I found myself rationing the stories in this collection, reading one each day and then walking the streets of Moscow, experiencing the pleasant dissonance of being a guest in a new country. In some ways, that’s what reading this collection feels like: a visit to a strange-yet-familiar land. Both a challenge and an invitation, this collection of stories possesses a dreamy exactitude, a precision of language and questioning that make its surreal elements feel both searingly intentional and necessary.

I Hold a Wolf by the Ears is Laura van den Berg’s third published short story collection. She is also the author of two novels, The Third Hotel and Find Me. I had the pleasure of speaking to van den Berg on the phone about crafting speculative fiction, the joys and trials of the short story form, and the magic of revision.

Interview

Yohanca Delgado: You write both novels and short stories. In a 2013 conversation with Elliott Holt, you mentioned that the stakes feel higher when you write a novel versus a short story. But I’m wondering, and I suppose this is the inverse of that: what do you think makes the short story special? What can it contain or what can it express that a novel can’t?

Laura van den Berg: The answer to that question initially is very personal. The short story was the first form of literature that I ever fell in love with. It was the first thing that I read and really connected with. I came to reading, really, and then as a byproduct of becoming a reader came to writing through the short story. The form has deep personal value to me because it was my portal to everything.

In terms of what I think is unique about the form of a story, what I love about a novel is it can have this sort of capaciousness to it, where it can accommodate many different worlds. That’s something that I find really interesting and dynamic about the novel—the way, for me at least, it naturally pulls me towards hybridity in terms of form and subject.

I think the story is a radically different project. To me, the story is so much about looking at something, a sliver of an experience, very carefully and also at the same time with brevity or a certain degree of brevity. I mean, there are many kinds of stories, of course, just as there are many kinds of novels, so the demands and the pleasures and the challenges of working on a piece of flash fiction are going to be different than working on a forty-page story. But I think that for me the way the short story works is like putting a grain of sand under a microscope—looking at one thing very carefully, but by magnifying that one thing you see all kinds of other things. Whereas with a novel—just to continue with that metaphor—you might need to really show a greater expanse of landscape. But I think the story is so much about honing in on something and then amplifying it in a way that allows us to see the strange and slippery dimensions of it that might not be perceptible otherwise.

I think the story is a radically different project. To me, the story is so much about looking at something, a sliver of an experience, very carefully and also at the same time with brevity or a certain degree of brevity. I mean, there are many kinds of stories, of course, just as there are many kinds of novels, so the demands and the pleasures and the challenges of working on a piece of flash fiction are going to be different than working on a forty-page story. But I think that for me the way the short story works is like putting a grain of sand under a microscope—looking at one thing very carefully, but by magnifying that one thing you see all kinds of other things. Whereas with a novel—just to continue with that metaphor—you might need to really show a greater expanse of landscape. But I think the story is so much about honing in on something and then amplifying it in a way that allows us to see the strange and slippery dimensions of it that might not be perceptible otherwise.

I think that’s something that comes up: why isn’t the short story more popular when we all seem to be developing the attention span of a goldfish because of social media and our phones and so on? I think it was Debra Eisenberg who said in an interview that people don’t read short stories more because it’s a very demanding form. It’s a form that tends to accommodate ambiguity and mystery and absence of resolution and ending in an unsettled space—even more so than the novel. Even in a novel with a great deal of ambiguity there might be resolution in certain areas, but I think with a story we begin on one cliff edge and we leave the world of the story on a different cliff edge. And we’ve traveled a great deal, but we haven’t necessarily reached a place of definitive resolution.

My undergraduate students, who maybe have read a lot of novels and are very avid readers of novels but haven’t read a lot of short stories, often remark on the ending [of a short story]. The ending leaves them in a sort of state of unsettled, unresolved mess. In that way, the short story invites us to continue to be in conversation with it, even after it has ended.

One of the things that I noticed about this collection in particular is a sort of push and pull tension. “Last Night” and “Carolina” are two examples that come to mind. There’s a sense of taking a protagonist, a point of view character, and forcing that character to look at something that they have actively avoided seeing. And I think it illustrates your point exactly, because it ends the story on a new and different cliffhanger. And there’s a pressure on the reader, too, I think in part because these are both first-person narrators. There’s an implication of the reader. The story says, “You have to look.” I’m interested in how that comes together for you, if you think about it that way when you’re drafting.

Initially, for “Carolina,” I had the idea of these two characters, a woman and her former sister-in-law, meeting at an airport. Then I wrote an opening scene and it felt flat. I was like, “I think there’s something here, but I don’t think that this structure is it.” Then I changed the location to Mexico City, where I had been recently and was thinking about. I had passed several large what appeared to be conference groups just out on walks and things. Also, the city was, when I was there, still reeling from the aftermath of this horrific earthquake. All of these atmospheric things converged and led to the idea that they intersect in Mexico City.

I was also interested in how to change the story if the power differences between these two characters were dramatically skewed. So, this former sister-in-law has been an American living in Mexico City but has lost her housing due to the earthquake and is living in an unsheltered state, and the narrator is an art historian, or restorer, who’s coming through on this conference and staying in this fancy hotel. They’ve always had this tense, conflicted relationship, but there’s also this really pronounced power dynamic in terms of access to shelter, to money, to food, all of these things, and how will that intensify the conversation between them.

I think so many first-person narrators have this dual impulse to implicate themselves and exonerate themselves. I think that that’s very true for the narrator of “Carolina”; she never was willing to listen when her sister-in-law tried to tell her that her brother was violent and that she was afraid of him. I think that there’s some residual guilt about that, but she also feels angry at her former sister-in-law for demanding that she be honest about her brother’s violence. There’s this desire to exonerate him and to exonerate her choices.

I think so many first-person narrators have this dual impulse to implicate themselves and exonerate themselves. I think that that’s very true for the narrator of “Carolina”; she never was willing to listen when her sister-in-law tried to tell her that her brother was violent and that she was afraid of him. I think that there’s some residual guilt about that, but she also feels angry at her former sister-in-law for demanding that she be honest about her brother’s violence. There’s this desire to exonerate him and to exonerate her choices.

I’ve been thinking, “Where does this story come from in a deeper way?” Certainly, I’ve been thinking about whiteness, and whiteness and femininity. If [white women] can’t address the violence of the white patriarchy in our own homes and in our own communities, what hope do we have for being a productive force—or a just force— in the wider world? I think it’s very common to not have that engagement. I was thinking about a character that was actively committed to not addressing male violence in her own family and thinking then, “What would lead a person to that place? What would lead a person to be in this really committed place of denial where she has been made very unambiguously aware that her brother was physically abusive towards his ex-wife, yet she’s unwilling to see it, and she’s unwilling to really see and hear her sister-in-law as a survivor?” I was interested in tracing the psychological tendrils of how this person got there.

And that story ends with the protagonist having to confront something else entirely.

It took me a long time to get to the ending of that story. Originally, I had it ending with her and Carolina. I feel like so much of writing is sort of like, “I know I have not arrived at the right destination but I have no idea what the right destination actually is.” So I just had to keep trying different variations.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about experimenting with taking the story in different ways and ending it in different places. I’m wondering how you think about revision.

I love revision. My students think of me as a revision evangelist. I think for me revision is everything. Writers revise in many different ways. I’m married to a writer and Paul, my husband, will incubate stuff in his mind for a really long time, like for years, and it doesn’t look like he’s working in the sense that he’s putting pages down and then, all of a sudden, he’ll write a draft of a book in six months. It will not be done, but it will not be way off the mark, as my first drafts usually are. He objects to that characterization, because he’s, like, “I revise for two years, it’s just this invisible process happening in the landscape of my imagination. But just because it’s not externally visible doesn’t mean it’s not occurring.”

So, there are many different ways for writers to revise, but for me the first draft is an attempt. It’s like putting down a shadow of a thing but you’re not even really sure what the thing is, so you just have the big shadow. Revision is really everything that comes after that. I think there’s sometimes this impression of revision as either a mechanical process or this grueling problem-solving thing, a punishment for not getting it right the first time. But for me, revision is all discovery. In some ways, particularly the first few rounds of the early stages of revision, it’s not so different from writing the first draft. I just have a little more information than I did with the very first draft.

Donald Barthelme has this great quote where he says something like: “There would be no invention if the mind could not move in unanticipated directions.” I think for a lot of us there can be this imaginative calcification that happens after the very first draft, and so I feel like the most important thing in revision is to stay in that phase of exploration, experimentation, and to get the mind moving in unexpected directions continually, draft after draft after draft. That’s something I think about a lot in revision. I think, again, in our drafts we are setting limits for ourselves in ways that we can’t even see. I think what revision allows us to do is to figure out how to dismantle and transcend those limits in later drafts.

I love that: revision as discovery. It speaks to something I notice about your stories—and I wonder if it’s a product of your revision philosophy— but there are several in this collection that completely subvert my expectations for where a story of this shape might be heading; they pivot. Again, going back to even that first story, “Last Night,” there was a move from this question: do they lay down in the tracks? And it was a pivot away from that in-scene tension to a much broader, more elevated question. How did you arrive at that ending?

That swerving of expectations is something that does often come in the later draft and isn’t necessarily present in the first draft. I think it may be useful, in answering this question, to talk a bit about “Last Night” and a bit about “Hill Hotel,” because those stories are in some ways the most autobiographical ones in the book. I’m hesitant to say that about “Hill Hotel,” because the conversation on the train is the only thing that is at all autobiographical. I’ve never lost a child, had a child, been divorced, etc.

But I did have a conversation that was quite unexpected and took a lot of unexpected swerves with a colleague on a train ride. We hadn’t seen each other in a while and I was expecting small talk, chit chat, and to catch up, but we ended up having this really deep, raw conversation about our families and death and dying and solitude. I was so shaken and moved by the time we parted ways. I had been thinking about a lot of the stuff that we talked about ever since. So, with that story, I tried to write it all on the train. That was my original idea for the story. It would be all contained on the train and it would be my version of a Hemingway story. The complexity of the moment would be the whole vibe: dialogue almost entirely.

I was really committed to that version and it was not good. Every time I read it over I felt very cringe-y. But I couldn’t figure out how to get beyond that initial attempt at a shadow to get to the thing itself, like I was talking about earlier. Then I was reading Denis Johnson’s posthumous collection, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, and Yiyun Li’s Gold Boy, Emerald Girl. Li is a writer who does wild and really interesting stuff with time. I love the way that Denis Johnson’s stories in that collection really make time feel very mysterious and capacious, and there’s a particular story in the Li collection called “Sweeping Past,” where there’s a big leap forward in time. I was like, “That’s it. This is what I need to do here. It can’t be held by the train in dialogue. I need to really broaden the temporal canvas.”

I was really committed to that version and it was not good. Every time I read it over I felt very cringe-y. But I couldn’t figure out how to get beyond that initial attempt at a shadow to get to the thing itself, like I was talking about earlier. Then I was reading Denis Johnson’s posthumous collection, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, and Yiyun Li’s Gold Boy, Emerald Girl. Li is a writer who does wild and really interesting stuff with time. I love the way that Denis Johnson’s stories in that collection really make time feel very mysterious and capacious, and there’s a particular story in the Li collection called “Sweeping Past,” where there’s a big leap forward in time. I was like, “That’s it. This is what I need to do here. It can’t be held by the train in dialogue. I need to really broaden the temporal canvas.”

Reading is a huge part of my process at all times. Reading two writers that I really loved helped me out of this imaginative box that I had put myself in, feeling like, “You have to have this whole story happen on this very short clock in this very confined space.” It reminded me that you can break time. You can leap forward in time and some stories require this larger canvas.

I think some stories, some real-life experiences, really resist fictionalization. I think my conversation with my colleague on the train was 100% one of those things. When I tried to write as it happened, it completely lost all of the intensity and wonder that it had in person. I really needed the material of fiction to capture what that conversation had been like and what the echo effect of it had been. I needed to animate the echo effect instead of just talking about it on the page.

Then, interestingly, “Last Night” is going to be the opposite. There’s clearly some invented material in that story, but that story is heavily autobiographical. I had tried to write that story using the material of fiction and a lot of invention and had failed again and again, so it was this paradoxical thing. Some stories really resist fictionalization and some stories demand it. “Hill Hotel” was one that demanded fictionalization and “Last Night” was one that really resisted it. And I think when I just followed the frequency of that first-person voice in “Last Night,” which is not my voice but is somewhat close to my own voice, I suddenly felt so free to move around in time-space stretches, in a way that completely cracked that story open for me in a way that had been inaccessible previously.

Finding the unexpected swerve comes down to really listening to the story. I created the story—I’m not necessarily convinced that the story has its own completely independent intelligence—but I think that that also means listening to the deepest and most secret parts of yourself and your consciousness. For me, it often takes draft after draft after draft to really get there and to really hear and see what the story needs and what the story wants to do. But if I can figure out how to listen to the story or the part of my consciousness where the story lives, that direction will always be more unexpected, more compelling, more interesting than what I will come up with if I’m just sticking to the surface of my consciousness.

You mentioned that both “Last Night” and “Hill Hotel” are sort of autobiographical. Going back to the question of what a form can offer, what do you see as the benefit in having a story that is autobiographical put into a fictive container as opposed to an essay?

That’s a great question, but I’d just like to clarify: the only thing that’s even remotely autobiographical about “Hill Hotel” in its current and final form is the conversation on the train. I just don’t want to misrepresent my own experiences. Everything else is from the workings of the imagination. Conversely, there is invented material in “Last Night.” Actually, there were versions of the story that I did write without the presence of any invented material, but it felt like that story was not possible, so I did need the material of fiction and I did need the architecture of fiction.

Everyone’s mind is so unique, and I think the way that my mind thinks about story is it’s just incredibly rare for me to think about something in the context of a personal essay. Often, I really can’t get to the thing that I want, or need, or hope to say without the presence of some kind of invented material. I think choosing to write in a different genre, I would’ve felt very constricted in a way that would’ve impeded my ability to tell the story.

I find this to be true when I try to move between essay and short fiction as well: this feeling of trying to capture something that happened and feeling like it needs something to pop onto the page the way that you experienced it, to get the piece to reflect the feeling that you’re trying to bottle in the first place.

Absolutely. “Last Night” is also a story, in some ways, about storytelling. It’s a story about how we narrate our own history, both to ourselves and to others. It’s a story about storytelling in terms of how our memories tell us a kind of story. To this narrator, at this moment in time, there’s this instability to how her own story has been revised through time, and this older version of herself is reasserting its force. I think there’s also something about fiction, too, when we are writing in that auto-fictional mode—where it’s fiction but it’s drawing from one’s own experiences or one’s own life—that creates a similar sort of instability. How much you conflate the voice of the first-person narrator with the author-voice, the voice I am speaking to you in now. How much do you take to be true? What do you take to be invented?

Absolutely. “Last Night” is also a story, in some ways, about storytelling. It’s a story about how we narrate our own history, both to ourselves and to others. It’s a story about storytelling in terms of how our memories tell us a kind of story. To this narrator, at this moment in time, there’s this instability to how her own story has been revised through time, and this older version of herself is reasserting its force. I think there’s also something about fiction, too, when we are writing in that auto-fictional mode—where it’s fiction but it’s drawing from one’s own experiences or one’s own life—that creates a similar sort of instability. How much you conflate the voice of the first-person narrator with the author-voice, the voice I am speaking to you in now. How much do you take to be true? What do you take to be invented?

There’s a natural tension around truth in certain kinds of fiction that are written so they’re pretty close to the bone of the writer’s own experience, and at the same time not presented as non-fiction. I was interested in the way that natural tension of form could also bounce off of the internal tension about narration and memory and personal history that the character is experiencing.

I think about this all the time: sometimes there’s writing that’s not called auto-fiction directly but in some ways invites the reader to nestle the story into their perception of the writer in “real life,” a sort of straddling of genre lines. And I think it parallels another kind of genre blurring that you do in this collection, between realism and the surreal. These stories creep into the weird, but aren’t necessarily defined by it. I think you’ve talked about it in other interviews as a kind of “weird periphery.” I see it as a kind of hallucinatory periphery; just out of the reader’s direct line of sight.

Yes. For sure. I am really heavily influenced by a lot of the writers of the fantastic. Julio Cortázar is one of my all-time favorite short story writers. I love Helen Oyeyemi. I love Kelly Link. Many writers of the fantastic, both contemporary and canonical, are really dear to my heart. This is sort of moving from the fantastic to science fiction, but I decided to read Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild, which I hadn’t read in a really long time. I’m just reading one story a day and I’m like, “These are fucking amazing. They’re so good.”

I have absorbed a lot of influence from writers who are working outside of realism, and I do think that’s probably kind of nudged me in the direction of the strange. But at the same time my own orientation on the page is to work in this sort of slipstream way, where the stories aren’t necessarily purely realistic nor are they purely naturalistic either. There’s space for the surreal and the strange.

I love your phrase “hallucinatory periphery.” That seems completely right to me. I mean, there are a couple of stories where a fantastic thing happens—in “Slumberland,” for example, there’s a literal ghost that manifests. A fantastic thing does actually happen. But I think in the majority of the stories they don’t necessarily make that unambiguously fantastic leap. Yet they do hew to that hallucinatory periphery, and I think part of it has to do with place.

I was born and raised in Florida and that’s where I am right now. I feel like I am in the hallucinatory periphery every time I go for a walk. Growing up here—I’ve lived here for twenty-two years—there were so many things that I took to be completely commonplace. Then I went to do an MFA in Boston and there were very few people who were from the south, let alone Florida specifically. Things that I would talk about or things that I would put in my stories, thinking I was writing dirty realism, people identified as surreal, strange, fantastic, etc.

I’ve been back here since early March and will be here at least through the summer. It’s so interesting to be back in this place that I know so well from childhood and to see it with a different gaze. My husband’s here. He was born in New York City and before we met, I don’t think he’d ever been south of New Jersey. The first time he came down with me to visit my parents my dad shot an alligator in our backyard.

Oh my god. Is that a thing that happens?

Yeah! It is a thing that happened. If I was just at home with my family it wouldn’t have struck as being so bizarre, but seeing it through someone else’s eyes…

As a New Yorker, I am stunned.

[My husband] was like, “Where am I?” But you kind of absorb the strangeness of place in a different way. I think in terms of aesthetic influence, there’s a lot of art and a lot of literature that’s been really formative, but I think the aesthetics of place have been really formative also.

And the world is deeply, deeply strange. It’s easy, in talking about Florida, to sort of skew it. That’s been something I’ve been thinking a lot about since I’ve been down here too. Of course, there is this strangeness but it is so much more nuanced than the media representation of Florida. I can slip into a sort of performative Floridian self where I start trotting out the alligator story, but I think it’s like any state. There’s deep strangeness but much of the strangeness is very quiet and nuanced and surprising. It’s not all alligators and Burmese pythons in your pantry.

And the world is deeply, deeply strange. It’s easy, in talking about Florida, to sort of skew it. That’s been something I’ve been thinking a lot about since I’ve been down here too. Of course, there is this strangeness but it is so much more nuanced than the media representation of Florida. I can slip into a sort of performative Floridian self where I start trotting out the alligator story, but I think it’s like any state. There’s deep strangeness but much of the strangeness is very quiet and nuanced and surprising. It’s not all alligators and Burmese pythons in your pantry.

I keep a journal for ideas but I’ve never been someone who kept a diary or a journal where I dump my thoughts. I was sort of like, “That’s what stories are for.” But I’ve keeping a diary since I’ve been here: doing these daily meditations on what it’s like and what I’m seeing and what I’m noticing. There’s so much depth and complexity and this is a beautiful thing to experience in a place that you know really well. I’m being surprised on a near-daily basis.

I think it was Mark Twain who said that reality is stranger than fiction, and I think if you look at anything for long enough it becomes inherently or surprisingly strange. I’m from New York City, which definitely has its own brand of weirdness.

Absolutely. And there’s so much that can’t be explained through logic. I think that’s where fiction is really a very adept medium in terms of getting inside the stuff that can’t be accounted for in a logical way or in a scientific way.

As someone who’s workshopped both essays and short fiction, I’ve noticed that a lot can happen in reality that people will not question but that will absolutely not hold up to the logic of fiction.

That’s a very interesting thing about the “Last Night” story, thinking about how some stories resist fictionalization. I got completely tangled up trying to write as fiction-y fiction this idea that you could be in an inpatient facility and that an orderly would actually let three people out for an evening jaunt, which 100% happened. But I was trying to build a fictional world where that was plausible. I actually really hate the word “plausibility” when talking about fiction, but writing a world where that was convincing was impossible, actually. I would get so tangled up in all this exposition about how this particular guy was always breaking rules, and it was still so not convincing. It had the quality of someone over-embellishing a story and the longer you listen the more you’re like, “I don’t think that’s true.”

The overcomplicated lie.

That’s exactly what it was. It did read as an overcomplicated lie. There was something really liberating in changing gears, taking the auto-fiction approach, to say, “I know that this makes no sense at all and is logic-defying in many different ways, and yet this is exactly what happened.” You dispatch with the improbability of it and just keep moving.

This is one of the reasons I like the stories in this collection so much. There’s a register they hit early on that suspends disbelief and imposes the fictive dream. They say: “You can trust me. I’m going to tell you a story and it’s going to veer in different directions but in the end, it’s true in the fiction sense of true,” which I think is really hard to do. I love that idea of intentionally leaning on realism and how we understand it, then weaving in the flexibility of fiction.

A convincing world in fiction has so much to do with voice and tone. For me, the process of revision is about finding the right frequency. It’s a bit like turning a dial on a radio and you’re like, “I’m cutting through it but it’s a little static-y.” Then, particularly in the first person, once I hit that frequency, the sense of the reality and tonality is built one sentence at a time after that, one paragraph at a time, one scene at a time, and so on. The solidity of the frequency will make all kinds of things possible.

A convincing world in fiction has so much to do with voice and tone. For me, the process of revision is about finding the right frequency. It’s a bit like turning a dial on a radio and you’re like, “I’m cutting through it but it’s a little static-y.” Then, particularly in the first person, once I hit that frequency, the sense of the reality and tonality is built one sentence at a time after that, one paragraph at a time, one scene at a time, and so on. The solidity of the frequency will make all kinds of things possible.

I feel like it’s such an aggressive question to ask a writer who has just put out a book, but… are you working on something new?

I think with the intensity of the COVID pandemic and quarantine and everything, it was very hard to work for a while. My family kept saying, “This must be great for your writing because you have all this time. You can’t leave home.”

On one hand they’re right, but to me, making meaningful work is about literal clock time, having literal time is certainly very important, but just as important—if not more important—is mental space and time. That was very hard to come by for me in quarantine. So, I read a lot, which helped revive my own imagination. I have been back to work for a while and I’m working in the sense that I get up and I write pages almost every day. What it is or what it will be, I don’t know. I’m in this space of not-knowing for right now.

You’re holding the wolf by the ears?

Yes. I’m holding the wolf by the ears, although hopefully there will be a way out that doesn’t involve me being eaten by the wolf; you can’t hold the wolf ears forever, but if you let go, the wolf is bound to bite you. Hopefully there’ll be a third option.