Anne Enright’s new novel, Actress (W.W. Norton & Company), explores an intense filial relationship between a writer, Norah, and her late mother, actress Katherine O’Dell. Looking back after her mother’s death in 1986, Norah considers how her life was shaped by their loving bond: a bond both strengthened and compromised by her mother’s celebrity and personal fragility. The complicated mother-daughter relationship is at the heart of the novel, a relationship freighted with burdens of secrets and fame, events in Ireland, and the expectations for women and men in the worlds of the theater and academia.

Some of these themes—family, gender expectations, Irish culture—are ones that seem central to Enright’s fiction. Though in an interview with Writer’s Bone in 2015, following her appointment as the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction and the publication of her sixth novel, The Green Road, the author pushed back against the way her work has sometimes been categorized, saying:

Actually, I don’t think I am writing about Ireland, sex, family, I think of myself as writing about some more fundamental problem like “compassion.” […] I think my problems are more…philosophical. I mean there is some question I need to figure out, so I sit down and write a book so as to see what the question might be. That problem is not “Ireland.” It is not “sex” or “family.” The problem is bigger, more vague: like, “How do we live?” “Who are we when we are alone?”

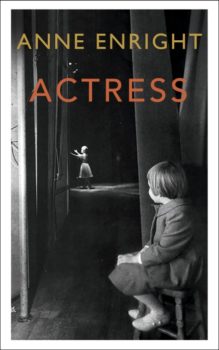

How do we live? Who are we when we are alone? Those problems and questions certainly resonate throughout the pages of Actress. But there is more as well. Speaking recently to The Irish Times about this new book, Enright identified another dynamic that she wanted to explore, captured by a photograph she kept pinned above her desk as prompt and talisman (the photo became the cover of the book in the UK). A child—Carrie Fisher—stands in the wings, gazing at her mother, Debbie Reynolds, spot-lit on the stage. Enright said, “I’m interested in that moment of glamour, which is almost a moment of loss as well. Once you see something so beautiful and false, you’re losing it at the same time. It’s about the beauty and it’s about possession and then losing the beautiful object to the world.”

The mother and daughter in this novel do love each other possessively, and as Norah grows up, as her mother declines, Norah both bears and bears witness to the suffering and shortcomings behind her mother’s glitter. Katherine’s currency of beauty and magnetism is almost spent just as Norah begins to come into her own quieter womanhood. Norah does not tell her mother when she is sexually exploited—she does not need to, her mother intuits the transgression—just as Norah similarly senses who threatens her mother. The two remain tied as though Norah were in utero; love and pain pass along the twisted strands of their shared DNA.

The mother and daughter in this novel do love each other possessively, and as Norah grows up, as her mother declines, Norah both bears and bears witness to the suffering and shortcomings behind her mother’s glitter. Katherine’s currency of beauty and magnetism is almost spent just as Norah begins to come into her own quieter womanhood. Norah does not tell her mother when she is sexually exploited—she does not need to, her mother intuits the transgression—just as Norah similarly senses who threatens her mother. The two remain tied as though Norah were in utero; love and pain pass along the twisted strands of their shared DNA.

And there is a lot of pain in these pages: intentional and unintentional cruelty, abuse, and misogyny. But Enright provides a rare and valuable counterweight: Norah is long-married—not easily, but abidingly—to a good man. Loving like this is Norah’s victory, and indirectly Katherine’s. Likewise, the author’s ability to feature a quiet, satisfactory marriage, making it interesting, is Enright’s—it is famously difficult to write engaging fiction about good people, and yet she accomplishes the challenge with grace. The couple’s story, shared life, and history is mostly off-stage, off-page, only hinted at. Nothing glittering or glamorous, but authentic. Norah describes their relationship with a loving blend of irritation and gratitude, acknowledging her recurrent surprise that they still wake every day together, that they have pulled it off even though “Our love has always carried its freight of dread.” Remembering their younger, sadder selves she wishes to “appear, like Princess Leia, in a little hologram…to plead or reassure, ‘Don’t worry, in thirty years’ time you will still be together.’”

As significant—or, more so—is the role that her unnamed, almost invisible husband plays for her as writer and narrator, which is that of listener—not audience, as she was for her mother. She counts on him to validate rather than idealize. And it is his suggestion she tell the story of her mother, after they quarrel about a journalist who wants to write about Katherine. She recalls:

You said I should write the damn book myself. […] We were in the kitchen, after dinner. A low sun was shining through my plants on the windowsill above the sink, where I had chili in a yellow tin pot, and supermarket coriander. At a certain moment, the window behind them flared in a silvered scrim of dust and grime, so you could not see through the glass for the dirt of it. I was really not in a great mood. “Why don’t you write it yourself,” you said. And not—if you don’t mind me pointing this out—in a nice way. Not in a long suffering, husband-of-the-writer-way.

She accepts his dare and tells her story to him in a monologue which streams on, even in the dark while he sleeps beside her. Though not chronological—the first part of the novel focuses primarily on her mother Katherine’s early history. Norah cannot tell her own story without telling her mother’s; her early memories are Katherine’s performative stories.

I used to do my homework at the kitchen table…while she romanced me with these tales of her youth. […] I was right there. […] I had been, all along. Because, tucked inside her on the day she shot out into the world, was the little egg of me. […] She told me that I was nested inside her, from the day she was born, like a little Russian doll.

After a rather slow start with these early memories, the pace accelerates as Norah moves into adolescence, beginning to claim her own separate life, and to narrate with more direct experiential authority. At first, I wondered why the author hadn’t chosen to start the narrative at this point of higher tension. Perhaps because the mother and daughter’s two inter-nested stories cannot be separated? Perhaps because Enright (through narrator Norah) wanted to reject the classic dramatic arc of conflict, crisis, and resolution? In her interview with the Irish Times, Enright speaks to this question, noting:

Sometimes I get people saying, ‘Could she just not write the book?’, you know, from A to B’. […] This [book] was more curly-wurly. I had a really curly-wurly book until August and then I decided okay, what would I lose by doing it much more chronologically?

For whatever tension Enright might risk by structuring the book “much more chronologically,” doing so allows the author to foreground the philosophical problems and questions of the novel rather than its drama. Or as Norah might remind us, she’s not seeking to titillate or sensationalize; she’s not telling a bio-pic, fan press story of Katherine O’Dell, actress, and her “overshadowed child.” Rather, Enright through Norah explores the nested, conjoined story of a mother and a child who love each other in a way heightened by who they are and circumstances, about who the child grows up to be and to love, and her struggle to come to terms with beauty, possession, and loss. And so the deliberate, child’s eye beginning allows Enright to illuminate for us the way a real relationship can exist with artifice, as two simultaneous realities, rather than one negating or superseding the other.

No image better captures this tension than a moment Norah recalls of her ten-year-old self and her mother standing before a mirror, admiring their reflections, before Katherine’s thirtieth birthday party. Her mother is dressed in a designer dress she first wore when barely pregnant with Norah. “There we were,” Norah recalls, “standing in front of her bedroom mirror, me outside the dress as she remembered me inside the dress, inside her.”

Enright works magic here, making visible in Actress the primal origin stories embedded in and surrounding our own, tracing the most intricate of spirals: a double helix—two strands of connected story—illustrating how truly inseparable we are from those we love, unable finally to either fully possess or truly lose the other.