What aspiring novelist doesn’t dream of early fame? Granted, it’s a willfully suppressed narrative—unwritten, unspoken, and perhaps for a noble few, unimagined—but most writers have contrived versions of a meteoric rise to literary success along with more prosaic early fictions. And, given the chance, who would shunt the regard of established authors, modest financial gains, and possible tenured teaching position that await?

What aspiring novelist doesn’t dream of early fame? Granted, it’s a willfully suppressed narrative—unwritten, unspoken, and perhaps for a noble few, unimagined—but most writers have contrived versions of a meteoric rise to literary success along with more prosaic early fictions. And, given the chance, who would shunt the regard of established authors, modest financial gains, and possible tenured teaching position that await?

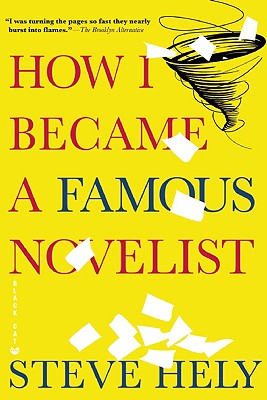

How I Became A Famous Novelist (Grove/Atlantic, July 2009), Steve Hely’s debut novel, uses this condition as pretext for rollicking satire. As a former president of the Harvard Lampoon and writer for David Letterman and Carson Daly, Hely is no stranger to wit. No one is spared: Hely lampoons the young writers who dream of success and the industries (publishing, entertainment) that award it, ably skewering stand-ins for popular fiction authors, serious literary types, and the books they write. It’s a stroke of brilliance that will surely make Mr. Hely, 29, a famous novelist.

Recent college grad Pete Tarslaw works a dead-end job at a company called EssayAides somewhere in the metro Boston area. He is charged with gussying up application essays for college and grad school. This is Hely’s first excuse to show us how good he is at writing bad, a talent that becomes one of his main comedic riffs in How I Became A Famous Novelist. “Warren Buffet has this word: ‘partnership’,” a Japanese native and hopeful MBA candidate writes. “The many cases of blemishing companies were cases when this did not partnership.” Of course Pete’s writing is a notch above the EssayAides clientele, and as an avid reader who prefers Moby Dick to “Boring Middlemarch and Jack-Off Ulysses,” he fancies himself the beneficiary of generally superior bookish taste.

But three years after graduating from the fictional liberal arts college Granby, Pete seems worse off than those whose essays he polishes. He pines for his college sweetheart, Polly, drinks himself to sleep every night, and is given to sad routines like ogling high school girls each morning on his way to work and lunching at a disgusting-sounding strip-mall diner called Sree’s USA Nepal Food Fun, where the only other regular is a “lopsided old man with chapped lips who always wore a New England Patriots parka, ate a Curry Hamburger, and drank a Bud Light. ”

The day he learns of Polly’s engagement to her new boyfriend, Pete strikes on a plan to haul himself out of this rut and exact revenge on his former lover, whose apparent happiness he resents. Inspired that evening by a television piece on best-selling author Preston Brooks, a homespun literary type who he considers a hack and a fraud, Pete resolves to become a famous novelist. Pete bristles as Brooks waxes on about the purpose of fiction and laments the state of contemporary culture. “We’d all be in better shape if my grandchildren listened to a Gwich’in elder for a while, instead of Lindsay Loohoo and Dee-Jay Stupid Face,” Brooks says.

Pete’s epiphany comes when Brooks is shown reading from his Katrina novel, Kindness to Birds, at Shenandoah College. There’s some more good bad writing from Hely here: one Mez Deveroux’s fingers are described as “rich in texture as a knitted throw rug, fitted into Gabriels’ palm, stained by motor oil and bacon grease.” Beyond Brooks’ overwrought, folksy prose, Pete likes what he sees: “Young women in little sweaters and tight jeans, pliant and needy” watching, rapt, “pleading with Preston to guide them and fill them with hard truths.” “Preston Brooks is a genius,” Pete decides. “He’s the greatest con artist in the world.”

Pete devises a formula that he hopes will catapult him to literary fame in just months, providing a platform for humiliating Polly at her wedding. This is of course by way of many other prurient fantasies involving his admiring female readership, and a general insensitivity to the purpose of fiction outside of the mass consumer market. “Write a popular book,” one of his rules states. “Do not waste energy making it a good book.”

While Pete can arouse the reader’s sympathy, he is—like everyone here—an easy target for Hely’s satire. Pete comes up with a list of “WRITERY STATEMENTS” for press-junket boilerplate, which includes “I’ve always felt that writing a novel is like doing surgery on yourself.” He creates a checklist of qualities of popular books—they must include a murder, for example, and obscure exotic locations and plant names. Hely is at his most hilarious when he provides excerpts from The Tornado Ashes Club, Pete’s supremely schlocky manuscript, which hit all those notes.

The book’s outline reads:

After a murder at the Las Vegas hotel where he works, Silas Quilter is accused of a crime he didn’t commit and forced to turn to the only person he has left—his grandmother. … As they dodge bounty hunters, we hear the tale that brought them together, a story of lost love that begins in the hobo camps of the Depression and on mud-stained college football fields, crisscrossing through the fury of World War II France to the islands of the Mediterranean and the kitchens and vineyards of Peru, a saga whose heartbreaking but uplifting end can only come in the swirl of a tornado, sweeping across the milkweed and bluestem of the prairie on a Christmas morning.

This is funny stuff, especially for a reader who happens to be an aspiring writer. Pete’s purple prose is truly gag inducing—all the more so because it reminds me of some stories I wrote in college, aping Cormac McCarthy (Pete even eschews hyphens and quotation marks—very Cormac):

In strewn banners that lay like streamers from a longago parade the sun’s fading seraphim rays gleamed onto the hood of the old Ford and ribboned the steel with the meek orange of a June tomato straining at the vine.

The idea that you have to be a good writer to parody bad writing is debatable, but Hely is very, very good at writing bad prose.

And the public in How I Became a Famous Novelist is very good at swallowing this “writery” tripe. After a week spent in a trial drug-induced fugue state at his aunt’s Vermont cabin, Pete has his manuscript, which a New York publisher immediately buys. Then following a quick series of promotional coincidences, Pete’s book lands on the best-seller list. He enjoys some of the trappings of fame while traveling to readings, book fairs, and Hollywood, where he discusses a film adaptation of The Tornado Ashes Club. He sleeps with a popular fiction writer he meets at a convention, drinks with one of his literary heroes, and slowly begins to reflect on his deeds, realizing what a charlatan he is, long after Hely has driven the point home for the reader.

Hely is circumspect in his satiric pose, never taking aim at specific people and institutions. Some of the characters might be Frankensteined from several actual novelists, but these are broad strokes. This obfuscation may be noble, or self-protective, given the author’s involvement in books and the entertainment machine. Either way, it’s a generous approach to becoming a famous novelist, compared to Pete’s more mercenary one, and expertly executed. Still, one wonders what Hely thinks of his own path to the literary limelight. He hasn’t so much crafted a piece of fiction as scaffolding for a collection of winning zingers and a few sustained arguments about the book industry. One wonders whether Hely’s next work will be another satire, similarly cloaked, or if he will attempt something more direct. The honest path to becoming a famous novelist is a question Hely wisely leaves open.

Further Resources

– Visit the website for Pete Tarslaw’s fictional fiction debut, The Tornado Ashes Club.

– Visit the website for Pete Tarslaw’s fictional fiction debut, The Tornado Ashes Club.

– Read Steve Hely’s take on the industry in an piece he wrote for The Rumpus called “The World’s Foremost Consultant on the Future of Publishing.”

– Hely’s first book, The Ridiculous Race, is a nonfiction account of an around-the-world race that Hely co-wrote with his friend, and competition, Vali Chandrasekaran.

– Enjoy more of Steve Hely’s satirical wit via his “Short Takes on Books That Don’t Exist: Eleven Essential, Imaginary Beach Reads For Summer” from the June 2009 issue of The Believer. Also, he’s penned a fake interview of himself with Time‘s Matt Selman.

– Support your local independent bookstore by buying a copy of How I Became a Famous Novelist.