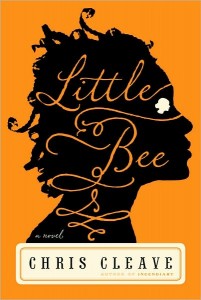

In his latest novel, Little Bee, Chris Cleave employs the same gifts that make him an excellent journalist: a keen eye for the crucial detail and the survivalist instinct to waste nothing, including his own past experience, which ranges from marine navigation to bartending to his West African childhood. Little Bee follows Cleave’s bestselling, and prize-winning, 2005 debut, Incendiary. What an encore. With a driving plot line and two strong, and very different, female narrators, this book may cause readers to miss their train stops. For a novel obsessed with the importance of names, it is fitting that Little Bee first appeared in England as The Other Hand. Perhaps it’s the disappearing honeybee, but America has bees on the brain: between The Language of Bees, The Secret Life of Bees, Bee Season, the film adaptations of the latter two novels, and the handful of other movies with apian titles (among them Bee Movie, Akeelah and the Bee), a book named Little Bee risks getting lost in the swarm. Cleave’s original British title is a subtle, interpretable image – perhaps less marketable, but stronger for the book. Twin titles prove an artistic echo for a story where the central characters have multiple identities. The novel, in its Little Bee incarnation, does have a very fetching cover that also alludes to these layers of selfhood.

In his latest novel, Little Bee, Chris Cleave employs the same gifts that make him an excellent journalist: a keen eye for the crucial detail and the survivalist instinct to waste nothing, including his own past experience, which ranges from marine navigation to bartending to his West African childhood. Little Bee follows Cleave’s bestselling, and prize-winning, 2005 debut, Incendiary. What an encore. With a driving plot line and two strong, and very different, female narrators, this book may cause readers to miss their train stops. For a novel obsessed with the importance of names, it is fitting that Little Bee first appeared in England as The Other Hand. Perhaps it’s the disappearing honeybee, but America has bees on the brain: between The Language of Bees, The Secret Life of Bees, Bee Season, the film adaptations of the latter two novels, and the handful of other movies with apian titles (among them Bee Movie, Akeelah and the Bee), a book named Little Bee risks getting lost in the swarm. Cleave’s original British title is a subtle, interpretable image – perhaps less marketable, but stronger for the book. Twin titles prove an artistic echo for a story where the central characters have multiple identities. The novel, in its Little Bee incarnation, does have a very fetching cover that also alludes to these layers of selfhood.

The difficulty of discussing this book – proclaimed on the inner flyleaf, no less – stems from Cleave’s knack for intricately timed revelations. Little Bee, a teenage refugee from Nigeria, carries one side of the narrative, young British professional Sarah O’Rourke, the other. Through this split-screen, Cleave tackles the multiple perspectives inherent in any story: someone always stands outside looking in. Perspective equals character, which makes his use of multiple names so interesting. Can a character exchange one set of eyes, one lens through which to view the world, for another? Little Bee offers the possibility of changing paradigms simply by changing names.

As the novel opens, Little Bee is being held at an immigration detention center outside London. The young Nigerian refugee renamed herself on the traumatic day that lies at the heart of the book, and now answers only to Little Bee. Armed with Andrew O’Rourke’s driver license, she makes her way toward the only man in England she knows. The other half of the story belongs to Sarah O’Rourke, who uses Sarah Summers professionally. Sarah runs an edgy women’s magazine, Nixie, and a household comprised of her husband, Andrew, a global-affairs columnist at the Times, who refuses to cut himself a break, and their 4-year-old son Charlie, who refuses to take off his Batman costume, even to sleep. They live in comfortable affluence, with the kinds of compromises one makes in adulthood, in a posh suburban home in Kingston-upon-Thames.

The intersection of those two worlds precipitates a chain of events that leads from a Nigerian beach to the labyrinth of the detention center to swarming London. In the opening pages of the novel, Little Bee declares: “I am here to tell you a real story. I did not come to talk to you about the bright African colors. I am a born-again citizen of the developing world, and I will prove to you that the color of my life is gray.” Her mission has teeth: a creed of anti-exoticism, direct confrontation of the world that is, not what one hopes to find. That raw world Sarah and Andrew must ultimately face, like it or not. The brisk plotting adds depth and nuance to Cleave’s characters, revealing all the messy contradictions of human beings, rather than simply transporting them from one crisis to another.

The crises of Batman’s life turn the miniature superhero’s obsessions – catching “baddies” and evading the evil Penguin – tragicomic. He’s a little boy coping with circumstances as treacherous as any arch villain. Charlie’s methods often prove more effective than those of his elders. The story sets up stark dichotomies between resignation and defiance, rejection and embrace, fear and love. Sarah and Little Bee must first understand how to survive. The main action takes place over one summer, when Sarah cannot convince Charlie to unmask, “It was one shock after another, in fact. At four years old, asleep and awake, my son lived at constant readiness. There was no question of separating him from the demonic bat mask, the Lycra suit, the glossy yellow utility belt and the jet-black cape. And there was no use addressing my son by his Christian name. … The only name my son answered to, that summer, was Batman.” Batman’s costume and quest for categorization – Is you goodie or a baddie? – may be the novel’s most honest approach to the grief of their collective predicament.

At times, Little Bee reads like a beautifully conceived philosophical dilemma laid out in an ethics class. It’s difficult not to ask, again and again, along with the characters: What would I have done? What should I have done? What can I do? One view of how to come through tragedy comes from Little Bee:

I ask you right here please to agree with me that a scar is never ugly. That is what the scar makers want us to think. But you and I, we must make an agreement to defy them. We must see all scars as beauty. Okay? This will be our secret. Because take it from me, a scar does not form on the dying. A scar means, I survived.

This spirit of survival, of overcoming, burns bright in Little Bee, both girl and book. During that central crisis of the story, a Nigerian hotel guard pleads with Andrew and Sarah to leave the beach, “Trouble is come here. You do not know my country.” Only as the novel progresses does it become clear just how true his statement is, the depth of the Western world’s estrangement from the civil and tribal conflicts of a country like Nigeria, the difficulty of really seeing and understanding another life. Little Bee lets us know that other world a little better by lending us her eyes, Chris Cleave by writing a marvelous story.

Further Resources

- – Read an excerpt from the first chapter of Little Bee.

- – Chris Cleave’s website offers a full Q&A about the author and the stories behind Little Bee/The Other Hand.

- – After a brief preview, Cleave tells viewers about The Other Hand.

- – Here are some interviews with Cleave: from Bookbrowse, from the Commentary, on Simon & Schuster’s author page, and here’s a review of The Other Hand from the Independent.