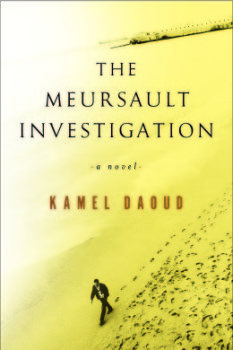

The Meursault Investigation, the debut novel from Algerian novelist Kamel Daoud, is a response to Albert Camus’ The Stranger, published originally in French in 1942. The Meursault Investigation has been critically acclaimed in France, receiving the prestigious Prix Goncourt for a First Novel. Its publication in the U.S. by Other Press this spring was heralded with an excerpt in The New Yorker, along with a cover story in The New York Times magazine.

The Meursault Investigation is, first and foremost, a story of desperation and revenge. You may recall that Meursault, the protagonist in The Stranger, killed an Arab on the beach in his own fit of existentialist desperation following the death of his mother. Daoud opens the novel by giving the Arab on the beach a name, an identity, and a pressing issue. “Good God,” begins Harun, the narrator of this novel and the brother of Musa, his murdered older sibling, “how can you kill someone and then take even his own death away from him?” He continues:

My brother was the one who got shot, not him! It was Musa, not Meursault, see? There’s something I find stunning, and it’s that nobody—not even after Independence—nobody at all ever tried to find out what the victim’s name was…

Musa’s death has indelibly marked Harun, who was a young child when his brother was killed. And the Arab mother, unlike Meursault’s mother, is most decidedly not dead; she has spent her life trying to understand and avenge Musa’s death. “As a child, I was allowed to hear only one story at night,” Harun recounts, “one deceptively wonderful tale. It was the story of Musa, my murdered brother, who took a different form every time, according to my mother’s mood.” He narrates:

Most of Mama’s tales… concentrated on chronicling Musa’s last day, which was also, in a way, the first day of his immortality. She wouldn’t describe a murder and a death, she’d evoke a fantastic transformation, one that turned a simple, young man from the poorer quarters of Algiers into an invincible, long-awaited hero, a kind of savior… In other [versions], he’d answered the call of some friends—uled el-huma, sons of the neighborhood—idle young men interested in skirts, cigarettes, and scars.

At the time of Harun’s telling of his version of the story—told to a nameless French researcher in a bar, using the second-person address of “you”—Mama has fallen mute. In the ensuing decades following the tragedy of her son’s murder, she spent her life in frantic recollection and supposition over decades. Though because she doesn’t speak French, and is illiterate, she could never fully investigate her son’s death, as French was the official language of Algeria until the 1962 liberation. This, however, has influenced Harun to learn French and to wield the language to resurrect his brother as a person, if not a fully-fleshed out character, saying to his audience: “Books and your hero’s language gradually enabled me to name things differently and to organize the world with my own words.”

So The Meursault Investigation is also a literacy narrative.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the literacy narrative constitutes a significant genre within Francophone literature, and as such, the genre has developed its own conventions: mostly told in the first-person, Francophone literacy narratives also employ narrative frames to set the terms for telling the story: in Meursault, it’s the nameless French researcher who has sought Harun to try to uncover the truth about Camus’ Arab.

And here, we come to an interesting twist in literary reception of both The Stranger and The Meursault Investigation: it’s important to note that, when the Algerian audience discusses The Stranger, Meursault and Camus are often seen as one and the same. As noted at the recent Contemporary French Civilization at 40 conference, in Algeria, The Stranger is understood to be a roman à clef if not outright confessional memoir. This speaks to the depths of distrust of the French during the Algerian colonial period (roughly, 1830-1962). The killing of an Arab by a pied-noir (literally, black foot, the term used to describe Algerian citizens of French origins) like Camus and Meursault were perhaps acknowledged in court, but as a whole went grossly unpunished, much like lynchings in the Jim Crow south.

So for Algerian society to jump to the conclusion that Camus is, more or less, Meursault, is not so far-fetched, and it’s part of how we must understand Harun’s experience: his brother was killed, and his murderer was essentially immortalized and lionized for the act in The Stranger. Through Harun, Daoud explores both the ethics of Camus creating a nameless Arab character to kill on the beach as part of a philosophical exploration, and the horror of a pied noir being canonized for killing an Arab. Harun never makes it clear whether he believes that Camus is Meursault; his comments on the subject throughout the novel could support either contention, depending on the passage. But it’s part of the reason why resurrecting Musa is so fraught: how do you develop a character for whom the terms have already been set, and for whom a philosophical justification for his murder has been long accepted and rarely—if ever, until Harun stepped on the literary scene—questioned?

So the attempt to resurrect Musa becomes its own philosophical gambit. We feel this sense of unsettledness even in the mise en scène: “[Algiers], with its thousand alleyways, was like a huge geological animal, and we were a little collection of lice on its back.” It is no coincidence that the setting is what unsettles from the start. As has been thoughtfully addressed in reviews such Robin Yassin-Kassab’s in the Guardian, The Meursault Investigation uses contemporary Algeria as an existential crisis in its own right. In this country long dominated by violence and instablity, Harun recalls that when he kills a Frenchman at the literal dawn of Algerian liberation from France in July 1962, he is interrogated by police not about whether or not he killed the man, but why he waited until liberation to kill a Frenchman. Much like Camus’ Meursault, who is on trial for not appropriately grieving his mother’s death rather than the act of killing the Arab, Harun’s crime is that he waited too long to begin participating in the bloodshed.

So the attempt to resurrect Musa becomes its own philosophical gambit. We feel this sense of unsettledness even in the mise en scène: “[Algiers], with its thousand alleyways, was like a huge geological animal, and we were a little collection of lice on its back.” It is no coincidence that the setting is what unsettles from the start. As has been thoughtfully addressed in reviews such Robin Yassin-Kassab’s in the Guardian, The Meursault Investigation uses contemporary Algeria as an existential crisis in its own right. In this country long dominated by violence and instablity, Harun recalls that when he kills a Frenchman at the literal dawn of Algerian liberation from France in July 1962, he is interrogated by police not about whether or not he killed the man, but why he waited until liberation to kill a Frenchman. Much like Camus’ Meursault, who is on trial for not appropriately grieving his mother’s death rather than the act of killing the Arab, Harun’s crime is that he waited too long to begin participating in the bloodshed.

With character development and setting, consider: when Harun kills the Frenchman (who does get a name: roumi [stranger] Joseph), he and his mother have begun living in the house of the French family whom she had served. (When the family fled Algeria, they asked her to live in the house so as to protect it until their return.) But it soon becomes clear to Mama and Harun that the family is never coming back, and they ease into warily inhabiting the space. Their first night there, they stay in the kitchen, but over the course of several days they begin to venture into, and occupy, the rest of the house. So when the roumi Joseph shows up, Mama not only cajoles Harun into killing him: she aims the gun and steadies his hand as he shoots.

In this story of desperation and revenge, in this literacy narrative, in this ghost story and portrait of a fragmented country, the narrative arc is not the easiest to trace. Nor will readers fully understand characters’ motivations, because their very characters have been thwarted from the outset—socially, politically, and culturally. But what can be parsed here is the masterful use of plot fragmentation, set in a country that’s mapped through its cracks and fissures. Don’t let the complicated story of France, Algeria, and indeed Camus and Daoud themselves as both writers and socio-political figures, intimidate you. The Meursault Investigation is a stunning literary work, both as a fiction debut and as a study in the artfulness of craft.